A Model Engineer Who Insists on Total Perfection—Building Every Part to Scale

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 1997

Jerry Kieffer is not a professional machinist. He retired as a representative for a Wisconsin power company, and most of his skills were attained through trial and error. Even so, Jerry’s home shop turns out some of the finest, smallest examples of model engineering in the world.

About Jerry Keiffer

Jerry Kieffer has not been a lifelong machinist. He developed skills in a broad range of areas mainly because he wasn’t satisfied with the work of others. Jerry often felt that he could do a better job himself, and acquired a versatile skillset as a result of his desire for perfection. Despite his lack of professional training, Jerry has applied his own expertise to projects involving watch repair, clock making, and model engine construction—to name just a few.

The first project to bring Jerry significant attention was his 1/30 scale Corliss steam engine model. The tiny bolt pictured below is a 1/30 scale version of a 1/4-20 bolt, used as a functional fastener on the model engine. Jerry developed a system of taps and dies to produce these tiny fasteners, so that the model would be scaled down completely to the smallest detail. Interestingly, he was only making the model because others had said that a running engine could not be made—completely to scale—at that small of a size.

In addition to his Corliss engine, Jerry has built a 1/6 scale running model of a 1947 Harley-Davidson “Knucklehead” motorcycle engine. He followed that up with a 1/8 scale version of the engine, accompanied by a fully-functional scale motorcycle model. Jerry’s ultimate goal was to be able to kick start the tiny Harley, and have all the functions down to the speedometer working. Additionally, Jerry has also completed a running 1936 John Deere tractor in 1/8 scale, along with several clocks, miniature machine tools, and other scale engine projects. Because of the wide scope of Jerry’s work, we have divided his craftsmanship into several sections, which are linked at the bottom of this page.

The tiny bolt and wrench pictured here are what first brought Jerry’s skills to the attention of Joe Martin. The .009” diameter hex bolt and nut are used as functional fasteners on Jerry’s 1/30 scale Corliss steam engine. Threads are only .0005” deep. Jerry also turned the knurled brass display bezel for the bolt and wrench. These miniatures are on display in the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum in Carlsbad, CA, along with some of Jerry’s other work.

Many of the projects that Jerry takes on are driven by the challenge. Whether it’s a challenge to himself, or one posed by a friend, Jerry has risen to the occasion again and again with his remarkable model engineering. The following article, published in The Home Shop Machinist, details Jerry’s miniature Corliss engine project, and lends some insight into what makes the master craftsman tick. Readers will gain a sense of just what goes into a project of this scale.

Sometimes Good Enough Just Isn’t Good Enough

One Modeler’s Quest for Uncompromising Accuracy Leads to a Magnificent Model—and a $1,000 Prize

The following article about Jerry Kieffer has been reproduced with permission from The Home Shop Machinist magazine.

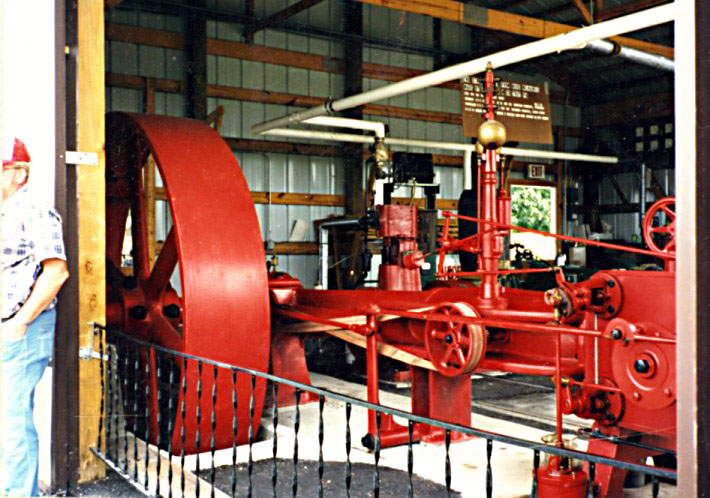

It seemed like a fairly straightforward project when he started. Jerry Kieffer of DeForest, Wisconsin wanted to build a model of a Corliss steam engine. He wanted to make it in a smaller scale than usually attempted, and he wanted no compromises when it came to scale. He saw the engine he wanted to model in a steam show in Sussex, Wisconsin, so he could get all the dimensions and pictures he needed from the original. The flywheel was ten feet in diameter, and he had a piece of 4-inch thinwall tubing from a truck driveshaft in his shop that would be just the right size if he worked in 1/30th scale.

Jerry had done some watch repair and had a selection of the smallest bolts, nuts and screws commercially available. So he figured when he got to the smallest parts, he would use those as fasteners. Jerry had never liked other models he’d seen where the builder compromised on the scale by using larger, non-scale bolts and pipes to represent the smallest parts. He wanted a running engine with everything to scale.

Jerry makes oilers of various sizes for different projects. The oilers are fully functional, and constructed just like the full-size originals—using glass, not clear plastic.

They Told Him It Couldn’t Be Done

Though he had no formal training in machining, and only about eight years experience as a hobbyist, Jerry was always good with tools and enjoyed working on very small projects. He built the flywheel first, and then parts of the cylinder—working his way down from the larger to smaller parts. By the time he had invested about a year and a half in the model—and had told several friends of his project—Jerry found that the smallest screws from a tiny lady’s wristwatch were still going to be much too large. They were twice the size of a regulator shaft that he needed to cross drill and bolt at a pivot joint.

Rather than give up on the project, or compromise on the scale of the smallest parts, he began to work on ways to make smaller and smaller bolts. The smallest bolts on the real engine were 1/4-20 size, which scaled down to a bolt smaller than ten thousandths of an inch in diameter—with hundreds of threads per inch at 1/30th scale! There was nowhere to go for advice on making threaded parts that small, as his friends in the hobby told him working bolts at that scale couldn’t be made.

This is the full-size Corliss steam engine that Jerry used as a prototype, taking detailed photos and dimensions. He made many trips to an antique steam museum in Sussex, Wisconsin where the engine was on display.

They Were Wrong

After many efforts at trial and error, “just playing with things until they work,” Jerry developed techniques of making extremely small taps and dies at the size and thread count he needed. From these he could make tiny hex head nuts and bolts. Still, there were no shortcuts in this process.

Many taps would be broken to make a single die; however, once he had a die, making the little bolts was relatively easy. In fact, if you ask him if it’s hard making bolts that small, he’ll tell you, “Making them is easy. It was figuring out how to make them that was hard.”

His Motto Tells a Story of Uncompromising Quality

When drilling holes in a steam chest that will eventually receive a number of these tiny bolts, it is not uncommon to break off a tap in one of the holes. When this happens, Jerry throws away the part and starts over. When asked why he doesn’t just drill out the broken tap with an oversize hole, fill it with a dowel pin, and re-drill rather than scrapping the part, Jerry replied, “Because someday, somebody is going to take this thing apart, and they’ll know I screwed up.”

Jerry simply refuses to compromise his goals for perfection at any level, even if it will probably never be seen by anyone else. He would know the mistake was there, and that is enough to make him redo the entire part until it’s perfect. Jerry goes on to say, “Most people are willing to do about 90% of the work on a project and then say, ‘That’s good enough.’ I guess my motto would be ‘Good enough just isn’t good enough.’”

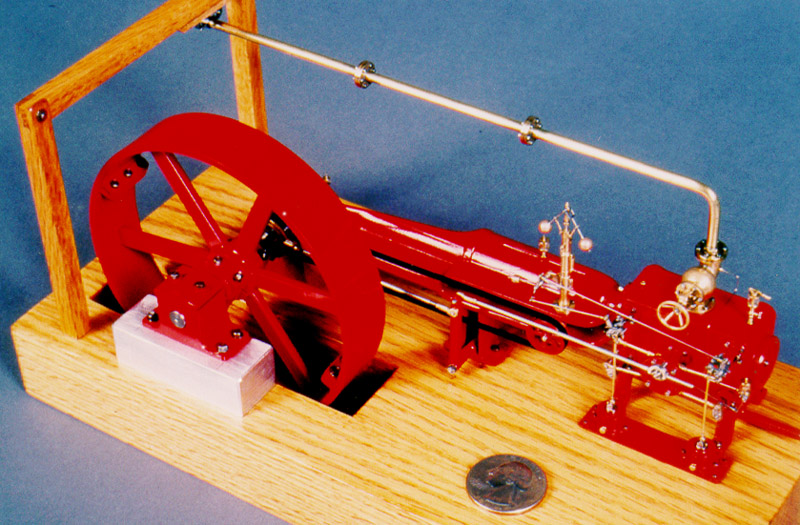

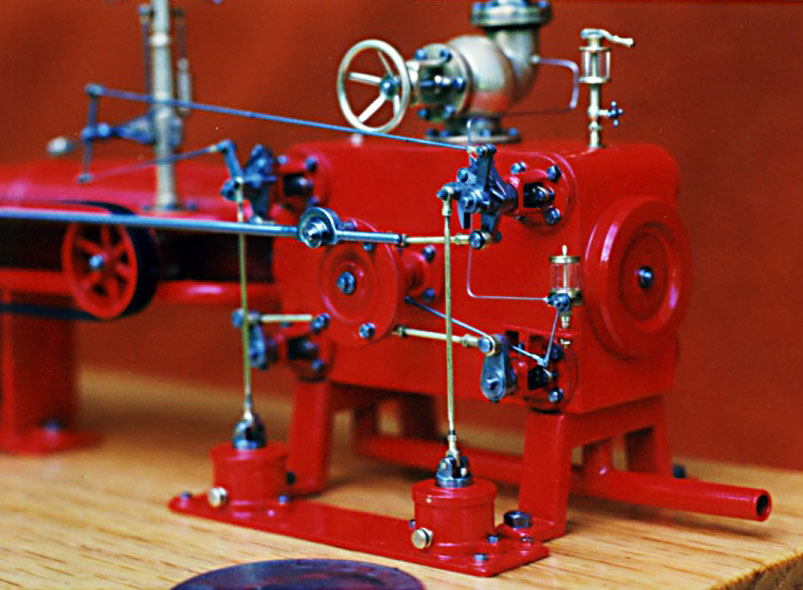

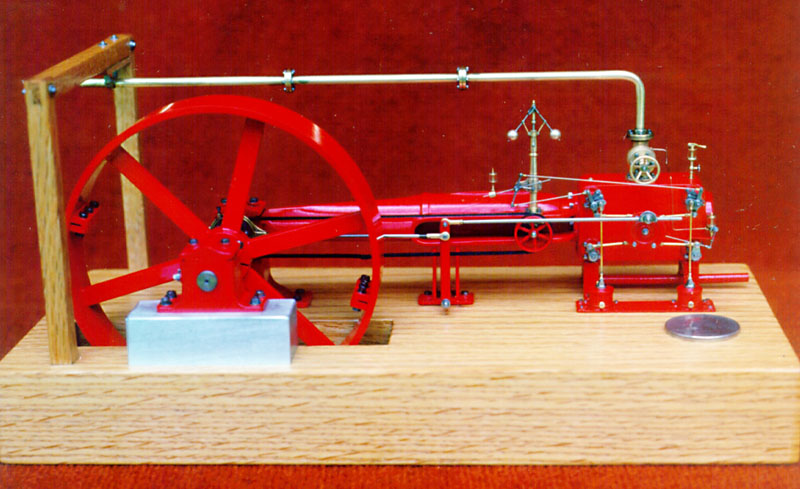

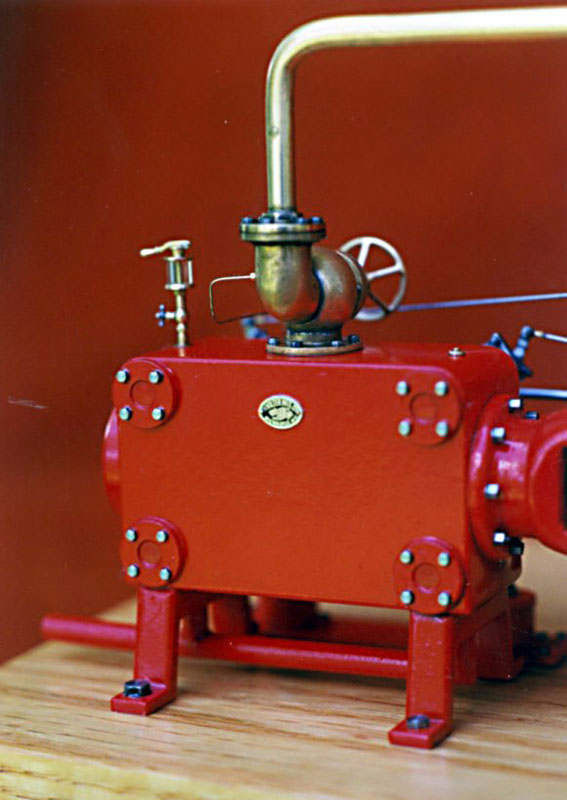

Jerry’s miniature Corliss steam engine was built to 1/30 scale in every detail. The dashpots pull an actual vacuum (instead of using hidden springs), and even the tiny oil lines are functional. The 4″ flywheel replicates a 10′ diameter version on the full-size engine, and it started out as part of a truck driveshaft.

The Details Are There—Even if They Can’t Be Seen

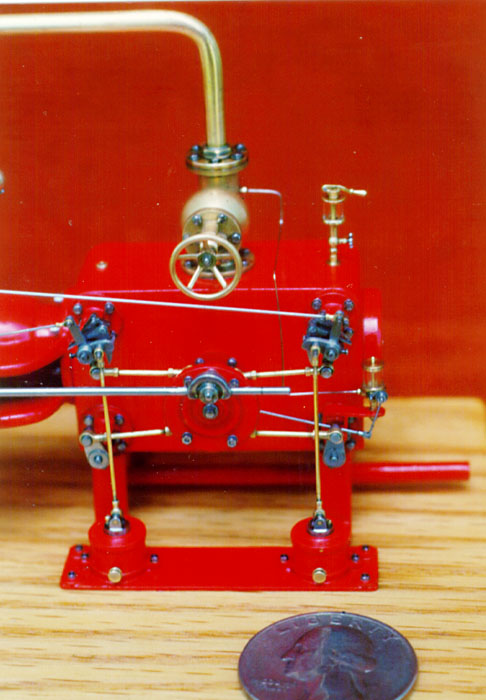

Each handwheel, lever and fitting is a miniature reproduction of the exact shapes of the original, and each presented its own problems and resulting solutions. Some details are not even seen once the parts are assembled, but they are there. For example, the model needed a very small, hollow oil line. Jerry finally located a company that manufactured hypodermic syringes, and purchased some of the very fine, hollow tubing used to make the smallest needles. He bent that to shape and made tiny compression fittings for each end so that the oil line is functional.

Just looking at it, there is no way to tell it is not just a piece of wire, but it is hollow and it does work—and Jerry knows that when he looks at his model. The real Corliss engine uses vacuum dashpots to retract part of the valve gear. On virtually every model of this type of engine, the modeler hides a spring inside the housing that actually retracts the rods, as no one looking at it can tell the difference. On Jerry’s model, however, the dashpots actually pull a vacuum to retract the rods. Yet another example of his total devotion to realism.

The hypodermic syringe material used for the oil lines can be seen in this close-up. Also visible is the hand wheel speed control, and some of the delicate linkages. A quarter placed at the bottom of the engine provides scale reference.

It Looks Great, but Does It Run?

Jerry lubricates the system with a few drops of light oil, and attaches a tube from a small electric aquarium air pump to the input pipe. Then, he gives the flywheel a gentle push and the little engine springs to life. Delicate adjustment with the tip of a finger on the regulating handwheel of only a few degrees produces an instant change in speed. It operates smoothly and almost soundlessly as low as just 3 rpm!

The tiny “banjo oiler” on the main bearing seems to hang suspended in space as the shaft rotates around it. The rods and valves circulate in an intricate motion as the cylinder pumps back and forth. It runs as perfectly as it looks. This model has made believers out of a number of “experts” who told Jerry it was impossible to maintain scale sizes down to this level, and to still have an engine that works.

The banjo oiler is designed to remain vertical as the shaft turns. The counterweight at the bottom keeps it that way. This creates an interesting motion, which is better appreciated when the engine is actually running.

Inexpensive Miniature Machine Tools Used to Make Tiny Parts

To complete the challenge to himself, Jerry made the Corliss engine using a Sherline Model 4000 miniature lathe, and Sherline Model 5000 vertical milling machine—which only cost him about $500.00 each. This should be encouraging to those who think that you need both years of experience as a machinist, and a big shop full of large and expensive machine tools to do good work. Jerry takes pride in letting people know that the projects were built with, “less than $1,000 worth of machine tools.”

Exceptional Craftsmanship Nets a $1,000 Award

For his work on the Corliss and other models he has completed, Jerry was awarded the honor of Craftsman of the Year for 1997 by the Joe Martin Foundation for Exceptional Craftsmanship. This annual award goes to craftsmen in various fields of miniature engineering, and is accompanied by a check for $1,000. Jerry was the first person selected to win this award. Jerry was a marketing representative for a Wisconsin utility company, and has only been working with machine tools in his spare time for about eight years—which makes his accomplishments all the more impressive.

Prior to this recognition, Jerry says the only thing he had won was, “a quart of oil for an entry at a county fair.” Jerry’s current work illustrates that some of the most interesting projects can be found at the small end of the size scale, and require little more than time and the determination to do a really good job.

Jerry brought a fantastic display with him for the NAMES Expo in Michigan. It featured his scale model Corliss engine along with some other small parts and tools. The models are all the more impressive when collected into one display case—truly revealing their tiny size.

More Articles on Jerry’s Work

Along with the previous write-up, an excellent article about Jerry and his home shop can be found in the April, 1998 issue of Modeltec magazine. An article about the Corliss engine was published in their September, 1997 issue. An article about his projects from the British perspective can be found in the April, 1999 issue of Model Engineer magazine. Jerry has also written an article about how to make oak finger jointed boxes to protect and carry your metalworking projects, which was published in the 2001 “Common Threads” issues of both The Home Shop Machinist, and Machinist’s Workshop magazines.

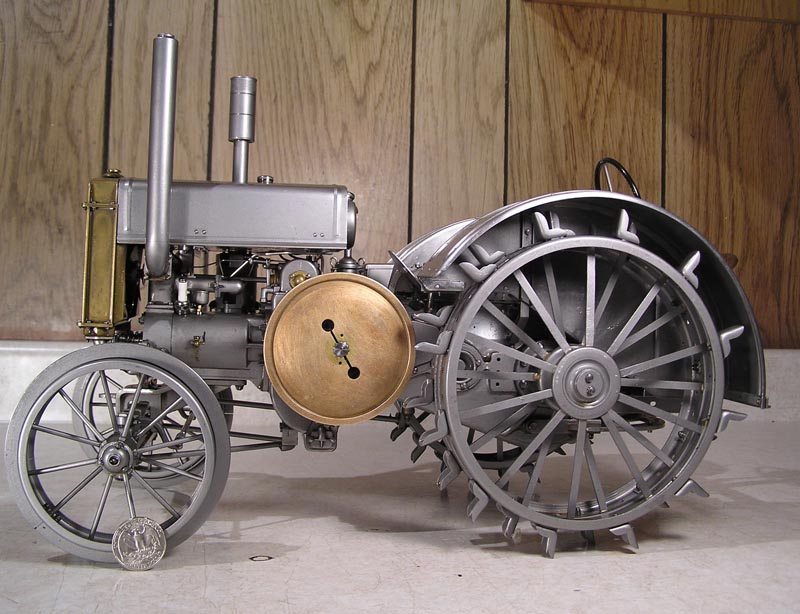

Among Jerry’s many projects is this 1/8 scale 1936 John Deere “D” tractor. Not only was the tractor built to scale in every way, but it also runs! This functional model is immaculate to the very last detail, including a scale Butter-Nut coffee can placed over the exhaust pipe—just as his grandfather had done on the full-size original. Below is a link to Jerry’s scale model tractor page where you can watch a video of the miniature actually running. (Photo courtesy of Mike Rehmus.)

Other Impressive Projects Have Followed

Since Jerry was selected as the Joe Martin Foundation’s first Craftsman of the Year, he has gone on to bolster that reputation by building a number of incredible projects. These include two miniature Harley-Davidson motorcycle engines, a 1/8 scale John Deere tractor, various clocks, several steam and gas engines, and other projects. Below are several links to pages covering each of these projects, with more details on their construction. Additionally, a selection of Jerry’s work can be viewed in this PowerPoint.

The following links will take you to each of Jerry’s separate model engineering pages:

This scale model tractor is fully functional. Jerry submitted photos of its construction and video of the tiny tractor running.

Jerry has made several small replica machine tools, all featuring his typically stunning detail.

Jerry’s construction of a 1/6 scale Knucklehead engine, as well as a nearly completed 1/8 scale full motorcycle. Read more about this model in an article by Vintage Motorcycle News.

Jerry has built a number of interesting steam and IC engines, a cam grinder, and other projects.

Jerry also makes clocks and clock tools, and teaches seminars at the NAWCC clock school. See his “Ignatz” flying pendulum clock here.

This section is sponsored by:

Makers of precision miniature machine tools and accessories. Sherline tools are made in the USA.

Sherline is proud to confirm that Jerry Kieffer uses Sherline tools in the production of his small projects.