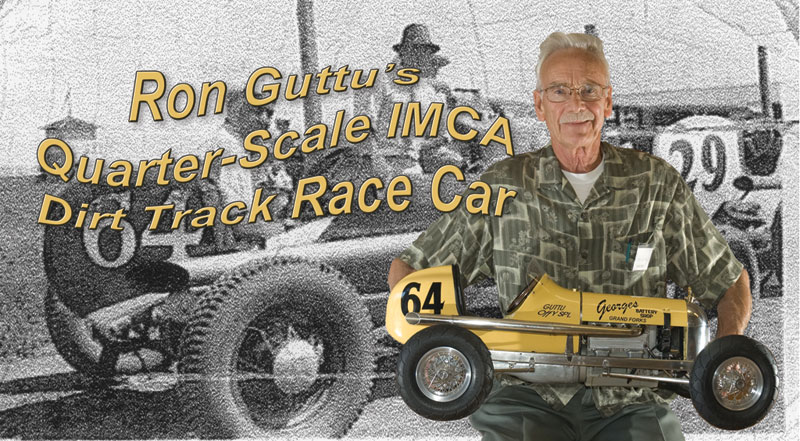

Building a 1/4 Scale IMCA Dirt Track Car With a Family History

Introduction

Ron Guttu’s father, George Sr., owned a battery shop and did general automotive mechanical work for a living. So it’s fair to say that Ron was raised around metalworking tools. In his younger days, Ron’s dad was a racer, too, building and driving his own dirt track car in the 1930’s. After Ron was born, his mother likely made it clear to George that his responsibilities as a new father precluded his role as a race car driver. Eventually, George had someone else start driving the car, and sold it altogether sometime between 1935-37. Ron, who was born in 1932, noted that his only memory of the car was the bloody nose he got as a youngster from bumping into one of the knobby tires. He held on to an old black and white photo of the car, though. It’s no surprise that Ron developed a love of engines at an early age, and they eventually became his livelihood.

Putting His Talent to Work

As a child, Ron had paid $35 for an old 6” lathe, which he used to make parts for the model airplanes he liked to build. After high school, Ron decided to follow his father’s suit with racing hotrods. He built and raced his own car on 1/4 mile dirt tracks in the late 1950’s. Ron’s first real job was at an automotive parts store. The store had a machine shop for grinding cranks, surfacing blocks and heads, and doing other auto jobs. Initially, Ron went to work there at the shop as a helper.

However, his aptitude must have been readily apparent, because after only two weeks of work the owner ended up putting Ron in charge of the shop! The old-time machinist who had held that job for many years suddenly quit, leaving the opening for Ron. Perhaps he had seen the writing on the wall once the talented youngster began working there.

Ron regretted that he didn’t have time to learn more about machining from old Joe, but he was a fast learner nonetheless, and he picked up knowledge on the fly. After four years of running the store’s machine shop, Ron decided to go into business for himself in 1964. He opened up his own auto repair shop.

Ron would run that business, with just one helper, for the next 35 years. In fact, he would run that shop until his retirement in 1998. Ron noted that when he first started, there was plenty of business because the older cars needed much more engine work than modern ones. As cars became more reliable, less machining was needed for repairs, and the job became less challenging for Ron. He finally sold the shop, and retired to pursue his hobbies.

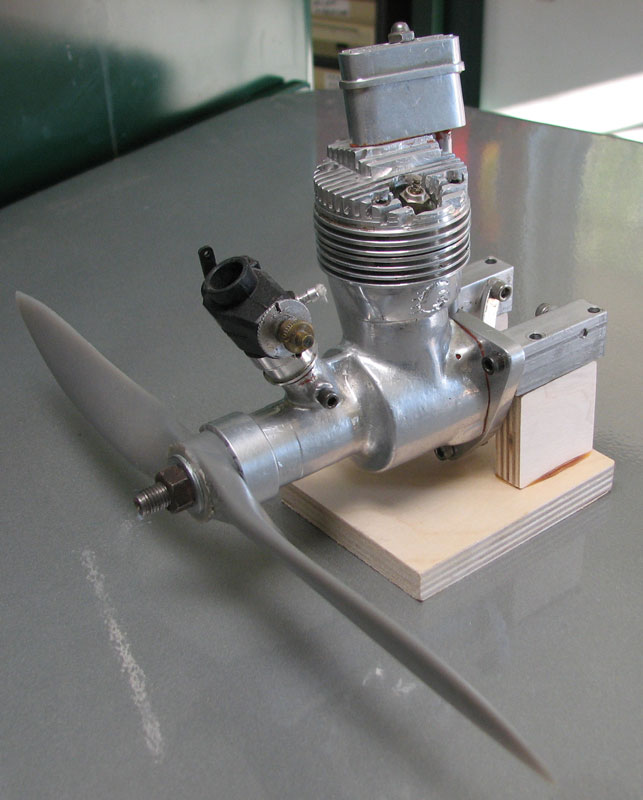

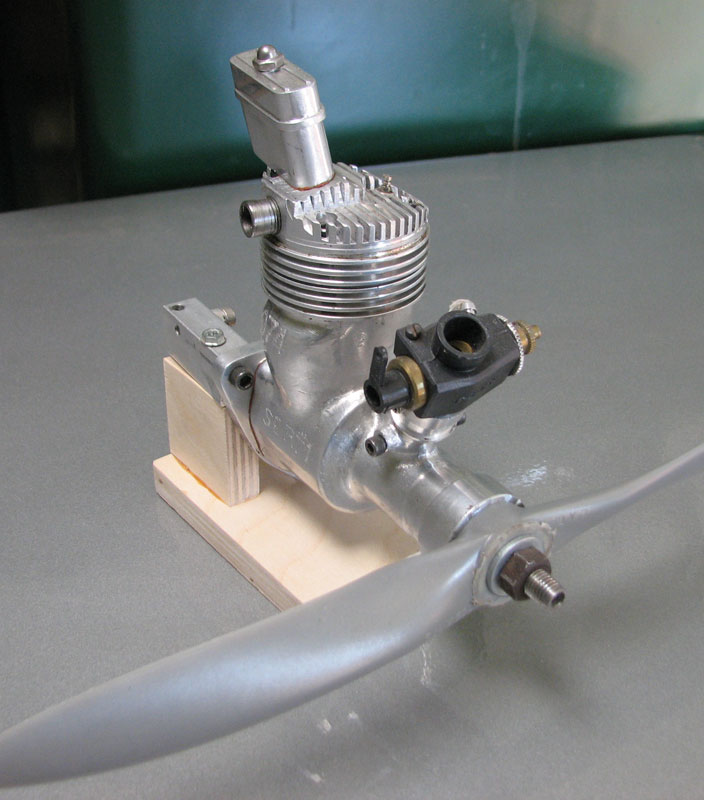

Ron’s first engine project was this Titan .60 built from a casting kit. However, Ron built it as a 2-stroke rather than a 4-stroke, and designed his own overhead valve for it.

Building Engines in Retirement

Sometime around 1998 or 99, Ron got another 6” lathe and dug out an old Titan .60 model airplane engine casting kit. He had been thinking about building it for years. While staying in Mission, Texas for a winter, Ron made his own overhead valve head for the model. He decided to finish it as a 2-stroke rather than a 4-stroke. After much effort, he was finally able to get the engine to run. In fact, the engine turned 7800 rpm while driving a 12” x 7” prop. After that, Ron made two more airplane engines from scratch. After coming across Ron Colonna’s 270 Offenhauser engine plans, he was inspired to make one of his own.

Now, anyone who has tried to build this complicated engine knows that it takes a lot of experience. Not only did Ron accomplish this build and get the engine to run, but he also made a few modifications along the way. He wanted to build his own Offy engine with older style carburetors, a slightly larger bore, and the head and block in one piece like the original.

The carburetors originally started out as model airplane carbs. However, Ron modified them to look like the original Winfield updraft carbs that were used for racing in the 1930’s. It was no easy task for a first major engine project. In fact, Ron remarked that after the engine was finished he had to have his two front teeth capped. They had become worn down from gritting his teeth, which Ron attributed to the difficulty of the build.

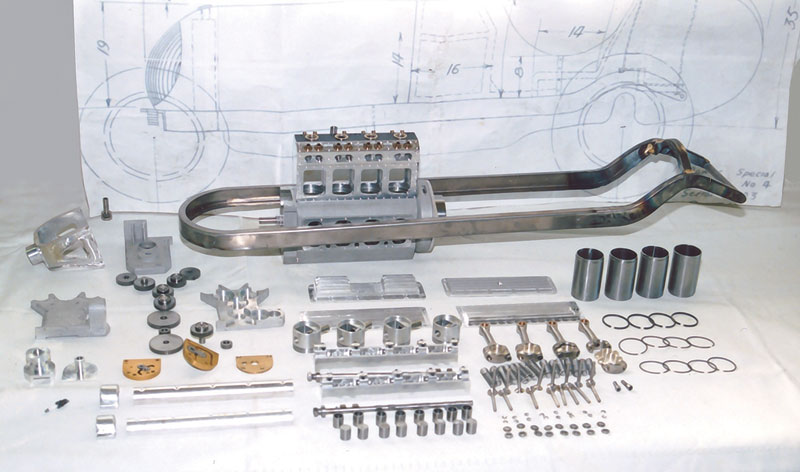

Once the engine was completed, Ron decided to make a race car frame for its display. He started by finding the old black and white photo of his dad’s 1930’s dirt track car. Then, Ron found a book of plans for building cars of that era, and started working on the frame. One thing led to another, and eventually Ron ended up building the entire car! At first, he blew up the scale drawings from the book for reference. However, Ron also did some sketches of his own to incorporate details of his dad’s car from the lone photo.

An Ongoing Project

The car is complete, but not completed. At the time of this writing, Ron still had plans to rebuild the carburetors. He wanted to make the bodies himself this time, instead of using parts from model airplane carbs. Ron was also learning more about molding and vulcanizing rubber tires. In doing so, he would be able to mold the knobby tires that were more prototypical of the older cars. Even so, the scooter tires that were originally on the car were a lucky find, because they fit the scale wire wheels exactly. They were only temporary, though, as Ron sought to do better himself. In this respect, the car would remain an on-going project as he continued to improve various parts.

The wire wheels took a month to construct, and Ron learned along the way that there are just some places you can’t take shortcuts. The components on the real car were made a particular way, which involved techniques that had been worked out over many years. Sometimes, it is best to simply duplicate those methods in miniature, rather than trying to come up with an easier way. More often than not, the easy way took longer, and didn’t yield great results. One example of this was an attempt by Ron to weld the wire wheel spokes to the rim. He ended up threading each one, and attaching them inside the rim like the real thing.

An Indoor Shop Allows for Year-Round Work

After making great progress on the car, Ron decided to upgrade his shop. The original shop occupied one stall of his two-car garage, but Ron moved everything into a special hobby room that he had built inside the house. Not only did that make for better climate control (the garage can get very hot in Sun City West, AZ), but it also meant that after 10 years Ron could finally park two cars in his garage again!

With regard to Ron’s shop, his tools include an inexpensive Harbor Freight lathe and mill. Even so, his expert hands are able to turn out quality work on them. Ron noted that his shop used to be very sloppy and disorganized, but building the new shop gave him a fresh start. Now everything is arranged to Ron’s liking, and he intends to keep it that way.

Ron’s revamped shop is a much more inviting place to work!

The following section is a reprint of an article from Model Engine Builder, with permission from the author and editor, Mike Rehmus. The article goes into more detail about the building of Ron’s engine and race car. For those interested in getting the centerfold shot of Ron’s car, back orders can be made for a copy of issue #16 of the magazine.

Ron Guttu’s IMCA Dirt Track Race Car

By Mike Rehmus

Reprinted from Model Engine Builder magazine (Issue #16) with permission from the author.

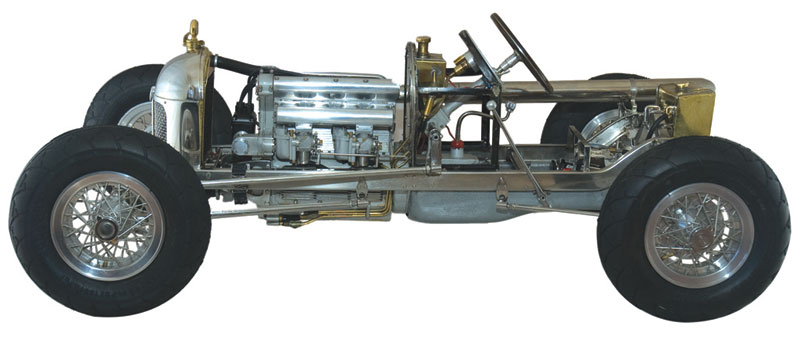

When Ron Guttu set out to create a quarter-scale IMCA dirt track race car similar to those his father built and raced in the 1930’s, Ron probably didn’t expect the model would turn out this polished. In only his second attempt to build a multi-cylinder engine, he built a Ron Colonna-designed Offenhauser 270 engine and created this scale race car around it. The scale race car is nicely sized and very good looking up close, as you will see in the series of pictures in this article.

Ron’s father is wearing the hat in the photograph (above) with driver Don Camoram in the car. This must have been the period when Ron’s mother put her foot down against dad driving. He owned a battery shop in North Dakota and mainly raced when the race series ran at tracks in the vicinity.

What is amazing to me is Ron built this in a non-air conditioned garage shop where the summer temperatures reach 120° F (ask me how I know), so his available building periods were somewhat restricted. He’s now building a new shop with AC and all the amenities. He is also fortunate to live in one of the few cities in the U.S. that has a metalworking club in a large and enviously well-equipped facility. I’ve visited that club and am quite jealous. One can start off by casting parts in the foundry and finishing them up on the CNC equipment without walking more than 100 feet. They even have a paint booth!

This 25 lb (11.4 kg) quarter-scale model has a scale 22-3/4″ (56.8 cm) wheelbase. His model is based on a chapter in the book, Automobile Racing, in which is found a detailed description of how to build a full-size dirt track race car. The prototype described in the book was a Bowles Oil Seal Special for those of you with knowledge of the early days of U.S. automobile racing. The book was published by Popular Mechanics Press in 1947. The car also conforms to what Ron remembers from his own racing days.

The Model

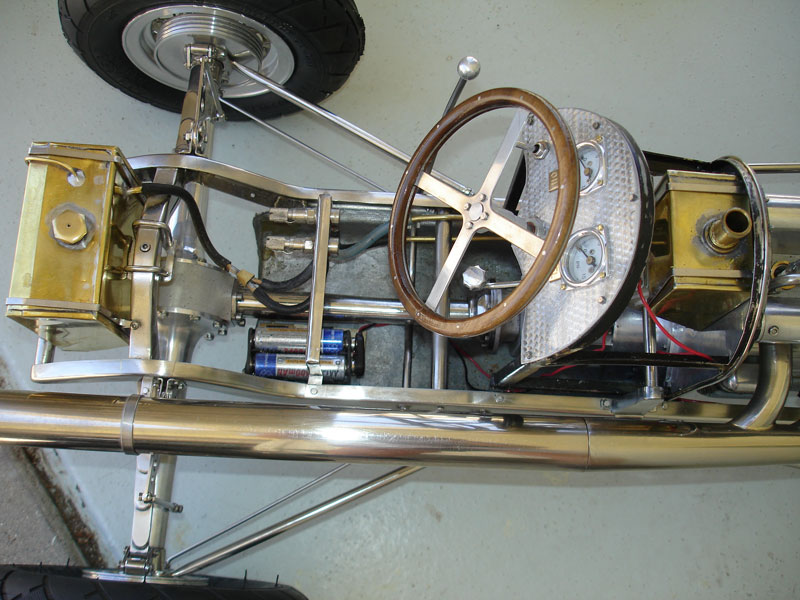

The frame and most parts are polished stainless steel to avoid having to chrome the parts like the full-sized cars. The frame is stainless steel sheet bent around a jig that helped him form it into the C-cross-section, and the entire frame is silver soldered together where necessary. The fuel tank, though hidden, is accurately scaled and does supply the engine. The suspension is pure scale Model A Ford just like the race cars, and uses hardened stainless steel springs. Radius rods fasten to the chassis as the originals did with screw-in end caps that captured the ball joint. The steering sector is from his old electric angle grinder.

The drive train is pure Model A Ford, and although the drive line is splined so it could take a scale multi-plate clutch, Ron has installed a centrifugal clutch with a 2-speed gearbox behind it (Model A, again). The rear end housing is aluminum, and the drive gears are from Savage 1/4-scale RC race car parts found in a local hobby shop. If you haven’t visited a hobby store lately, you will be amazed at the inexpensive and high-quality gears and other mechanical parts that are available for RC cars.

Wire wheels were built by Ron, with each containing 48 spokes made from 1/16″ stainless welding rod, swedged on one end and threaded on the other 0-80. The spoke nipples screw onto the spokes from the inside of the rim just like the full-sized wheels. Ron used a fixture to align rim and hub, then inserted the spokes and uniformly tightened each nipple until the wheels ran true. The knock-off hubs are splined just like the full-sized car.

Full-size bodies are metal, but after his experiment with a formed aluminum body, Ron chose fiberglass. However, unless you look closely it is not noticeable, and the finish is superb.

The radiator top section is a corner of a serving dish that just happened to be of the proper radius. The sides of the radiator shell are stainless sheet, and the stainless steel grill was found in the stores of the metalworking club. The thermometer in the radiator cap works, and the cap’s flip lock works as it should to gain access to the radiator.

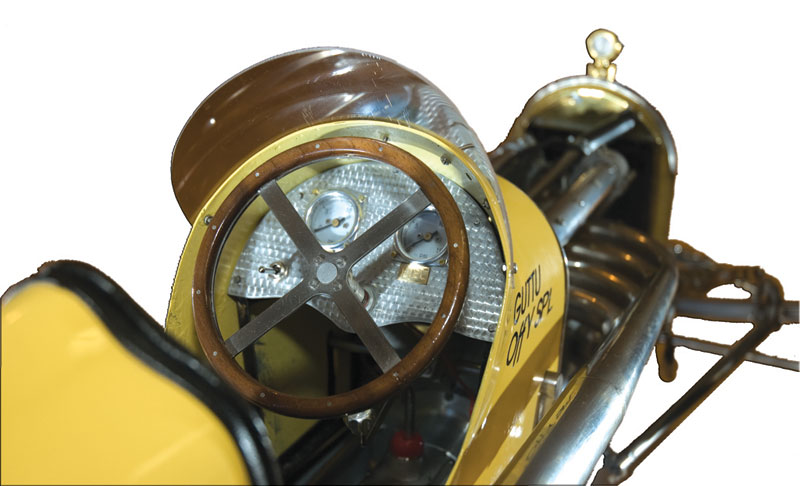

The steering wheel is cut from sheet stainless steel. The rim is laminated with walnut wood and looks similar to the riveted wheels that can still be purchased from automobile specialty stores.

Tires are from a Razor scooter, and are close enough until Ron makes molds for scale tires. Upholstery is leather taken from a ladies purse purchased in a yard (jumble) sale and sewn by the local ladies sewing club. The model windshield is made from Plexiglas purchased in a hobby shop.

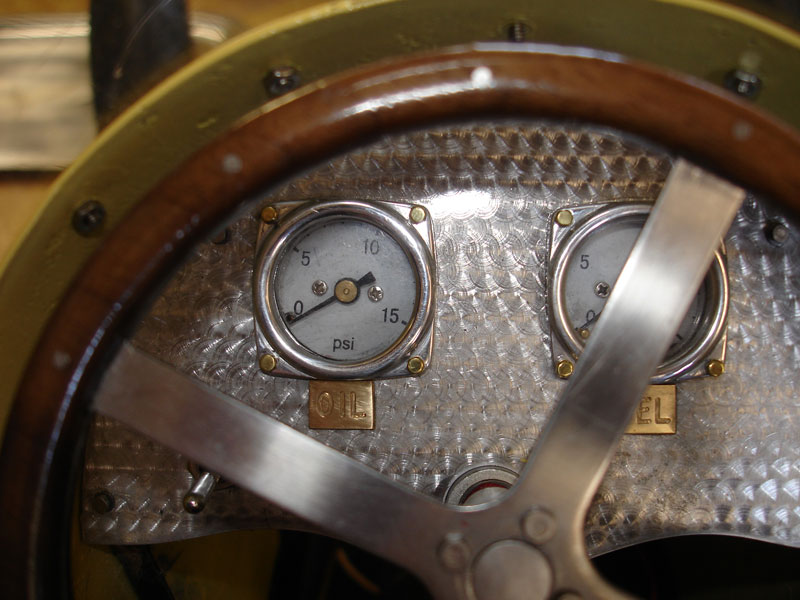

The two 1/4” gages were purchased and then modified to appear scale sized on the driver’s side of the dashboard. The bezels were machined by Ron to appear in scale. The ignition switch is the smallest he could find at Radio Shack.

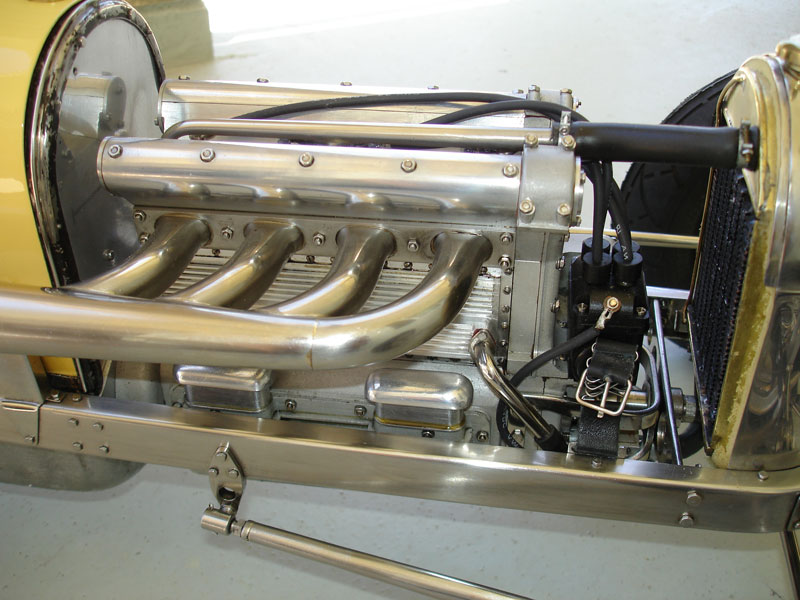

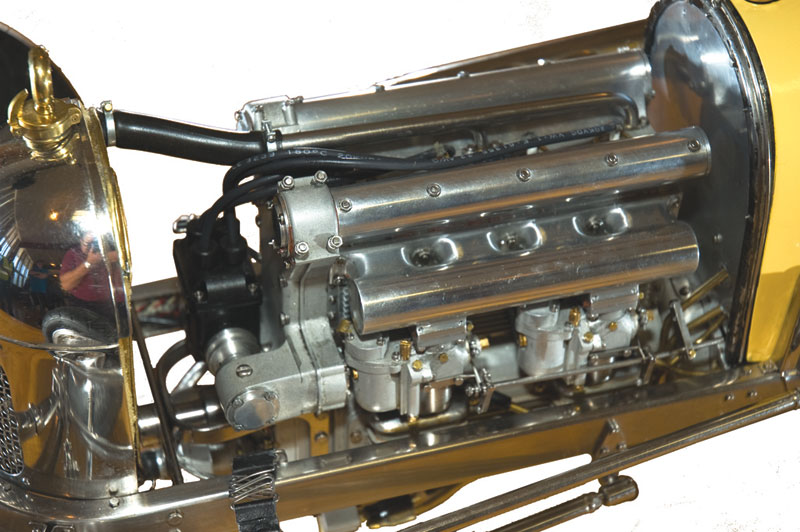

The engine is a 16-valve double overhead cam with pressure oil feeds and dry sump lubrication. Displacement is 60 cc (4.22 cubic in.) with 1.078″ bore x 1.156″ stroke. Compression ratio is 9.5:1. It uses solid state spark ignition (Hall Effect with dual magnets). The CD ignition module is mounted in the radiator shell under the radiator.

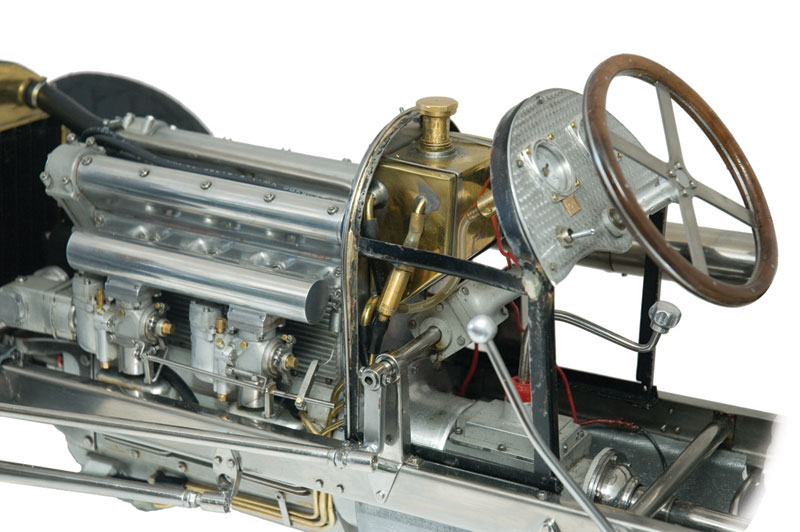

A close-up of the engine compartment. The magazine article also includes a full two-page spread centerfold photo of Ron’s complete car.

The reason for the centrifugal clutch is that Ron intends to add radio control so he can drive the car. Importantly, that control will be through a scale model race car driver who is radio controlled, and whose hand and feet operate the car’s controls. There will be no radio control equipment installed in the car proper. (Ron already knows we want a build article on that radio-controlled car driver.)

Ron would like to thank Paul Knapp for bringing the car to the 2007 WEME show where we saw and photographed it, and Ron Colonna for the engine design.

Ron retired after owning a 2-man automobile rebuilding shop for 35 years. He has built three single-cylinder model aircraft engines of about 75 cc displacement. He then purchased the Colonna workshop manual on the Offenhauser engine, and took (his words) a big chance on machining the cylinder block and head in one piece as in the original engines. He also changed the bore and stroke to give a slightly larger displacement than Ron Colonna’s plans. It does run well.

—Mike Rehmus

This is the most recent photo of the scale model car, taken after the article was printed. Notice that the car now has new scale knobby tires.

View more photos of Ron’s exceptional craftsmanship.