Steam, I.C. Engines, Guns, Tools—George Has Modeled Them All in Miniature

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2016

Introduction

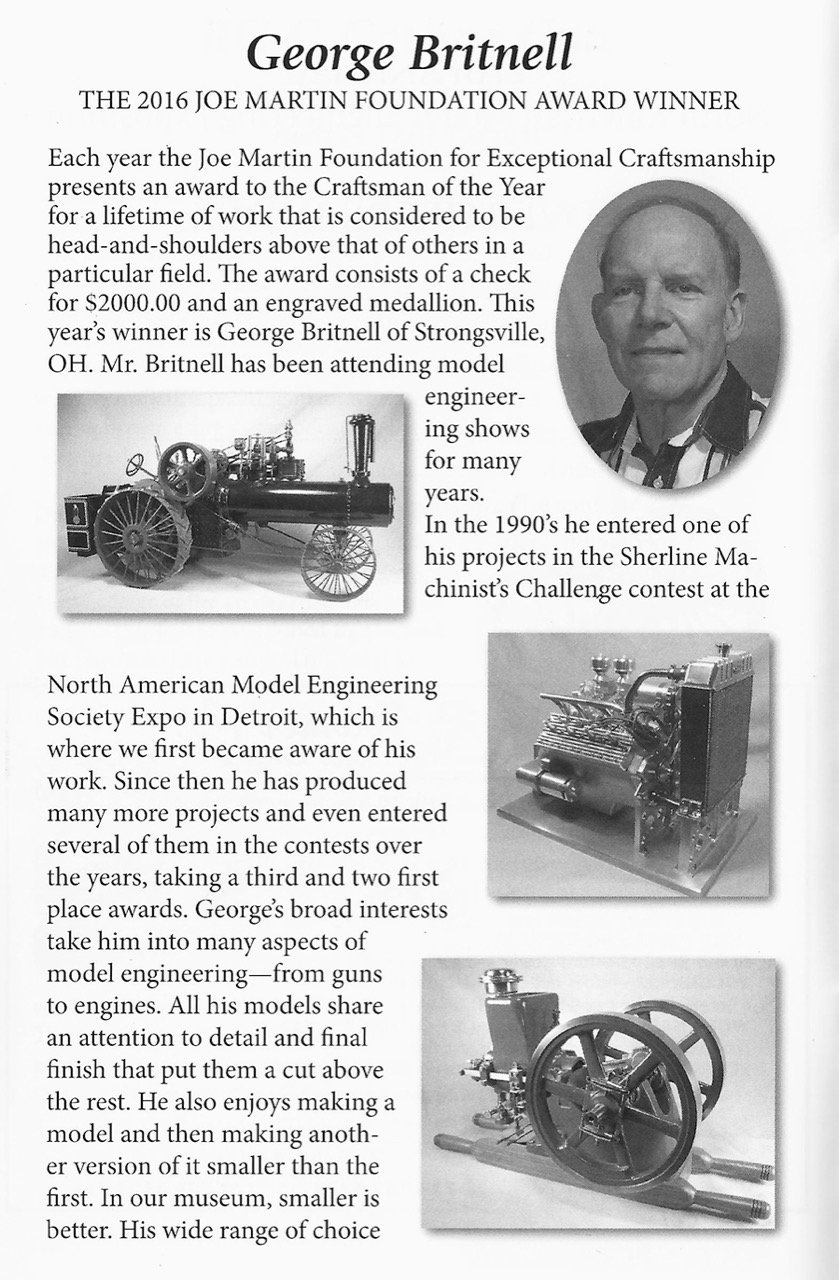

George Britnell has been attending model engineering shows for many years. However, it wasn’t until the 1990’s that he would enter one of his projects in the Sherline Machinist’s Challenge contest at the NAMES (North American Model Engineering Society) Expo in Detroit. That was where members of the Craftsmanship Museum first encountered George’s work. Since then he’s produced many more projects, and even entered some of them in later contests over the years—taking 3rd once, and 1st place twice.

George’s broad interests have led him into many areas of model engineering, from guns to engines and more. All of George’s models share an attention to detail and final finish that put them a cut above the rest. He also enjoys making models, and then taking on the challenge of building another even smaller version of that same model. Here at the Miniature Engineering and Craftsmanship Museum, smaller is generally better!

Additionally, George’s wide range of modeling projects have demanded a varied set of skills. Fellow craftsmanship award winner Lou Chenot noted of George’s work that, “It should be emphasized that while machining is the basis of what model engineers do, and is what articles and most conversations concentrate upon, George builds miniatures that require experience in sheet metal work, painting, careful woodwork, polishing, and perhaps casting and upholstery. I think that a complete model may only be 20% machining, especially if fixturing and setups are taken into account.”

About George Britnell

To start, George Britnell was born in Canada and lived there until he was 10 years old. He noted that he’s always enjoyed building things. George’s first recollection was carving a helicopter out of a block of balsa wood based on an illustration from a comic book. He was only about 7 years old at the time.

About a year later, his father made a trip to the U.S. looking for work, and ended up bringing home a plastic model kit for George. Now that was really something! Then in 1955, his family moved to Cleveland, Ohio where George’s father had been hired by Ford Motor Company as a wood patternmaker.

Despite his early interest in building, George’s experience with machining wouldn’t start until he was about 14—when he was introduced by an older fellow in his neighborhood. This gentleman had a small machine shop, and one day while rooting around the shop George found an old Dunlap lathe.

Everything was there except the motor, and the man offered to sell it to George for $25.00. After finding a motor and hooking it up, George’s early machining efforts didn’t get too far. His work consisted of little more than making chips!

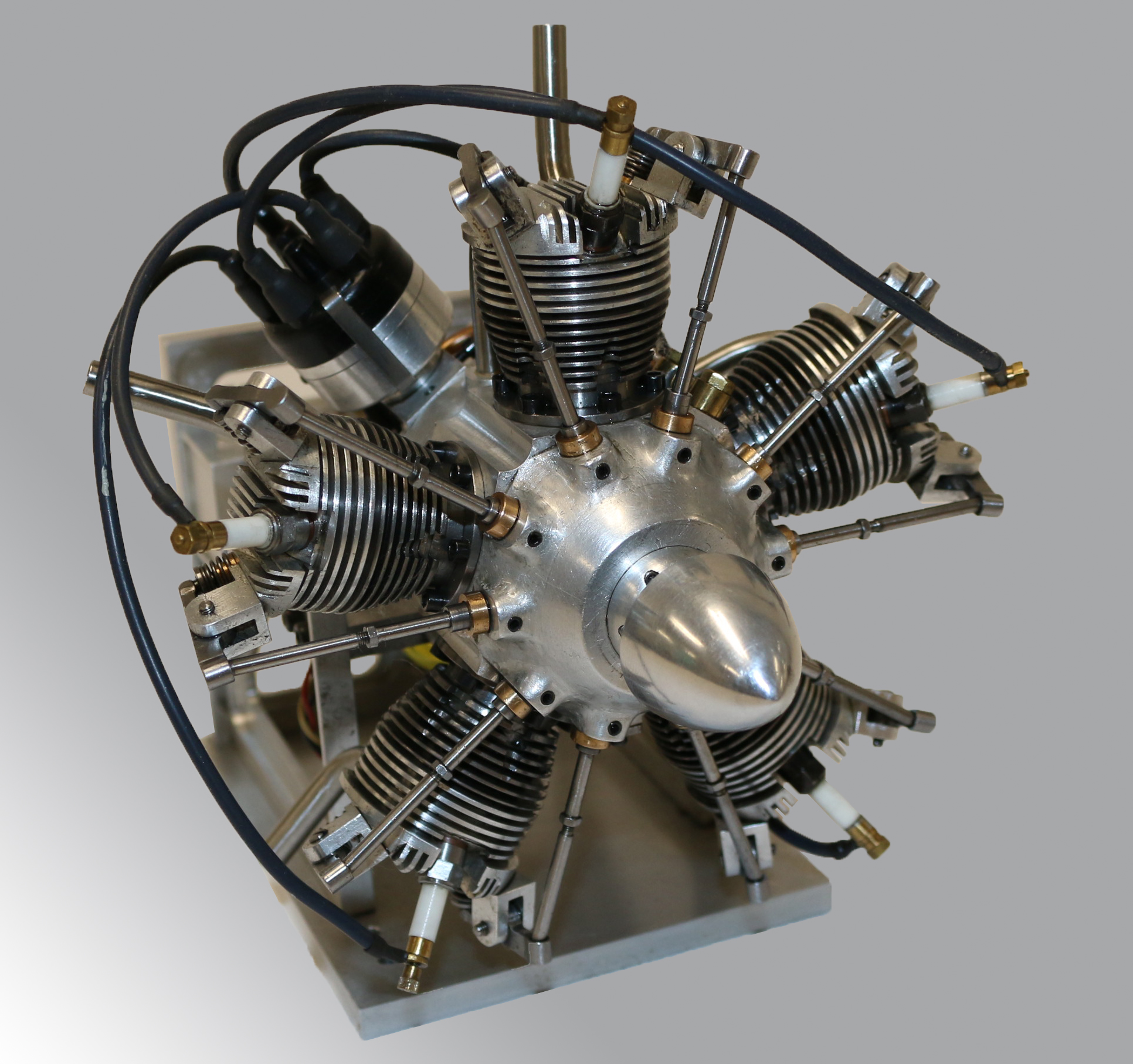

On display at the Craftsmanship Museum—George’s original design radial engine. Both designed and built by George Britnell. This engine is loosely based on the commercially available Morton M-5. Built in 2012, it has a bore and stroke of .625 x .600.

Later on, when he was about 17, George found a place in Cleveland called the Dennison Pattern Works. They sold Stuart Turner kits, and had completed versions of most of them on display in their office. From then on George was hooked. He bought the Stuart Turner Oscillator, and remarkably he still had the piece at the time of this writing.

However, George’s early machining career didn’t take off right away, as cars and motorcycles took center stage in his life at that point. In high school, he mainly took college prep classes—but did manage to sneak into the metal shop on occasion to hang out with his buddies. George took a course in mechanical drawing, but that was the only industrial arts course that he would attempt.

After graduating from Brunswick High School in 1963, George attended Cooper Art School in Cleveland with the goal of becoming a commercial artist. Although, he was only able to attend for about a year and a half because he needed to find work to pay the bills. So George worked in the art field in some capacity for a short time until he was drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War.

Despite being pulled into military service, it was in the Army that George’s machining education grew. Although he was initially trained as a radio repairman, the machine and maintenance shop needed people, so George was recruited. He worked with a German fellow who would teach him some of his early skills.

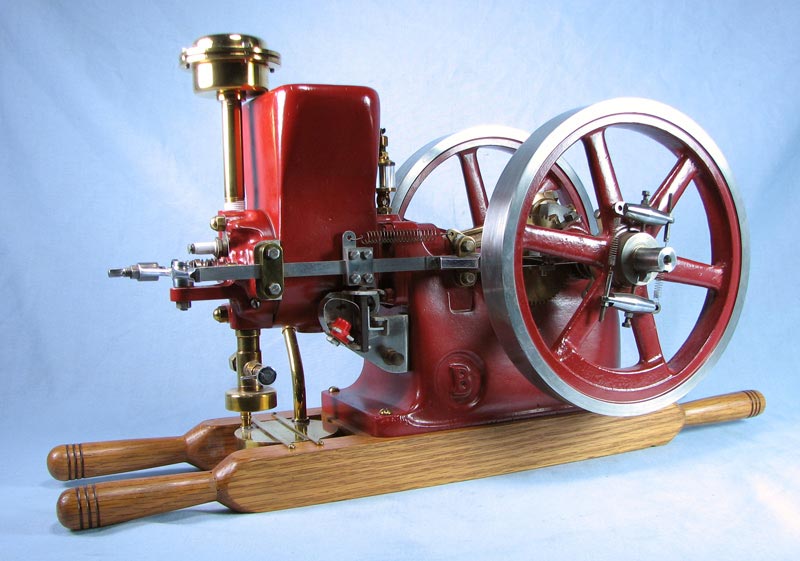

A Gatling gun in about 1/8 scale. George researched this through the public library system, gathering patent information and pictures from books.

After being discharged from the service, George tried to get back into commercial art, but didn’t have much luck. He worked several jobs until they opened up the apprenticeships at Ford Motor Company. With Ford, George was offered the choice of electrician or metal patternmaker—he chose the latter.

Fortunately for George, the apprenticeship was extremely comprehensive. Additionally, in that environment he was surrounded by a large number of skilled craftsmen. Through that experience, George would gain the foundational machining knowledge which carried over into all future endeavors. Now that he was working and bringing in a reasonable income, George was also able to purchase his first serious lathe—a 6-inch Sears/Atlas with all the attachments.

Over the years, George made a number of parts and engines on that lathe. Around 1978, his local tool store started importing Enco tooling. George wound up buying one of the first mill/drills in the area. He was still using that machine at the time of this writing! It may have had some shortcomings, but George remarked that it was still a very good tool.

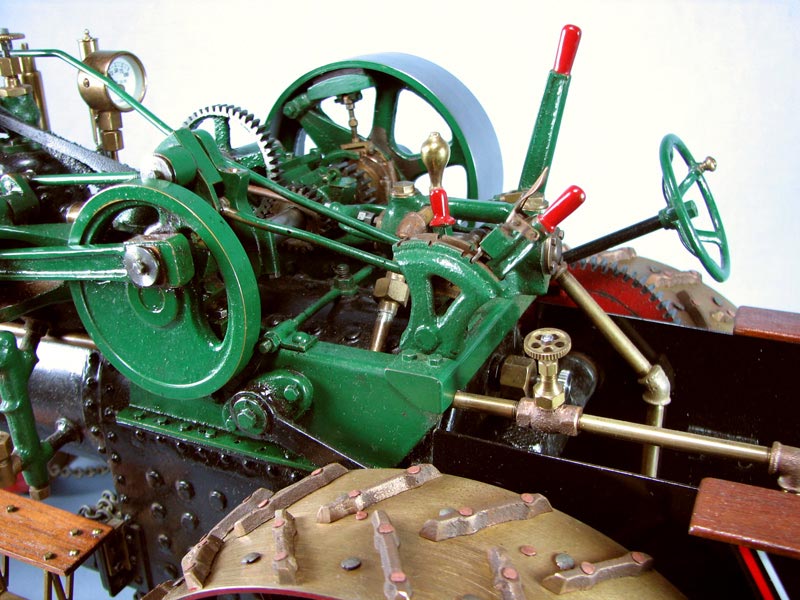

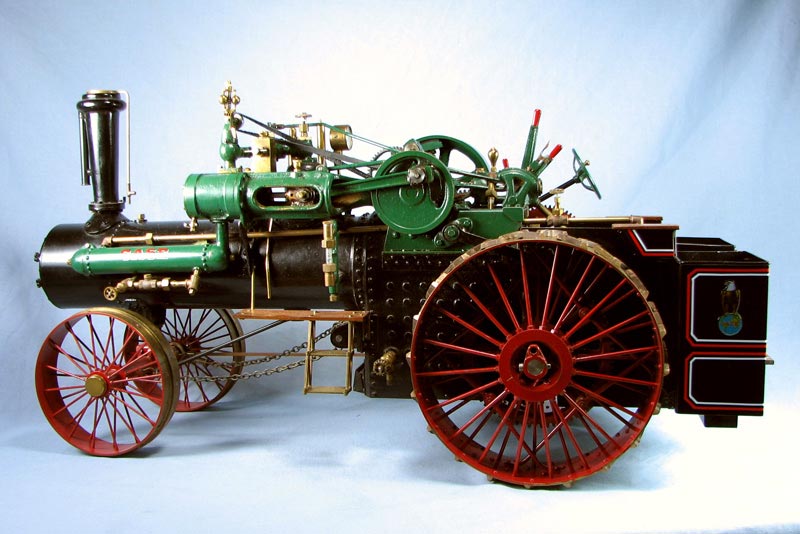

At that point, George started building a lot of Stuart Turner kits. Once he had saved enough money, he bought the Cole’s 1-inch Case traction engine kit. This was quite a departure from the Stuart kits, and George learned more about set-ups and fixturing during this build.

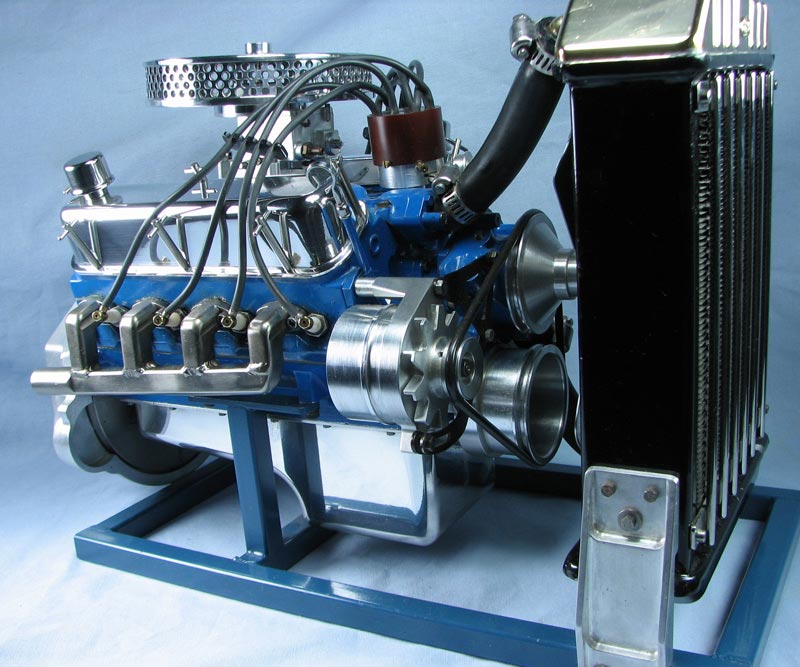

Moving on from steam engines, George got into internal combustion engines through the casting kits offered by the late Paul Breisch. Having considerably more knowledge and confidence, George started building the 1/3 scale 302 Ford engine. Because he was at Ford, George could access the engineering drawings for parts which were cast at the foundry there. He scaled them down and made the necessary changes for them to work as miniatures. The total time for this project was around 3 years. George didn’t keep track of the exact number of hours it took, but he estimated it to be around 2000. At times, he wasn’t sure that it would ever get finished.

Naturally, George’s work at Ford took him into the realm of pattern designing. This would evolve into computer modeling and cutter pathing for the pattern shop. Additionally, he had the opportunity to learn AutoCad and several other CAD programs during this time. He used these tools to design and build some of his own engines—namely an inline overhead valve engine for which he has offered drawings. George also designed miniature saw mills, hay balers, rifles, pistons, and many other small tools and projects.

Sharing Knowledge With Others

As of this writing, George was still selling copies of his extensive CAD drawings for select engine plans. He also shares a great deal of knowledge by participating in several online machining and engine forums. These include the Home Shop Machinist magazine forum, the Home Model Engine Machinist group (HMEM), and the Model Engine Maker (MEM) forum.

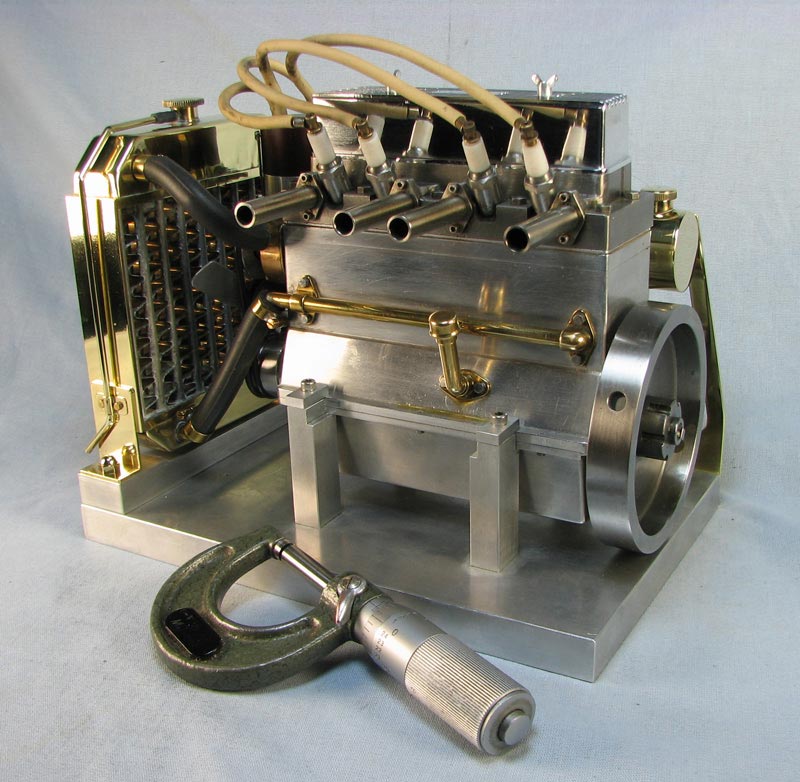

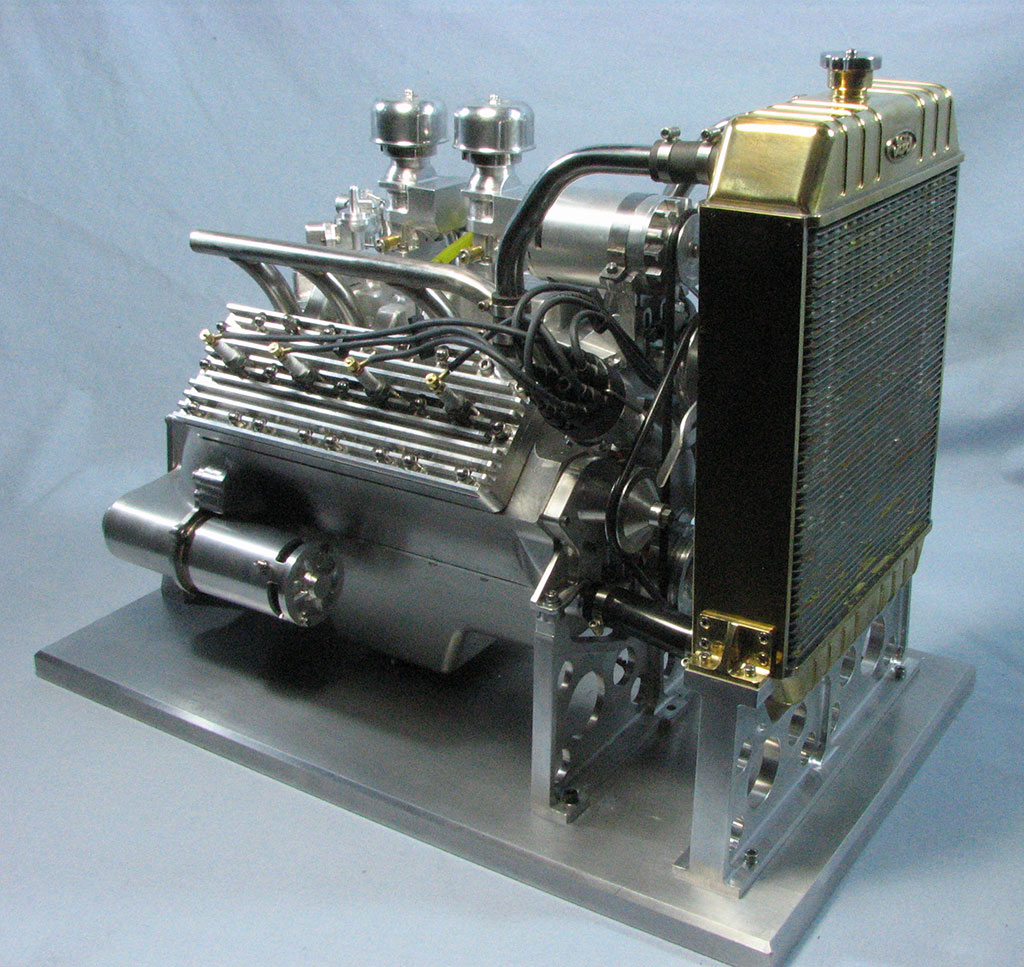

Latest Project—A Ford Flathead V-8 in 1/3 Scale

One thing that George had always wanted to build was a true Ford Flathead V-8 engine. However, after extensive research and drawing he realized that the only way to make it perfectly accurate would require making castings. Even then, the outcome would be very questionable. At any rate, George started the detailed drawing set in August of 2014, and finished the engine in December of 2015. At that point, over 1900 hours of work on the drawings and engine had gone into the project—with further modifications ongoing. Other than the exhaust placement, the engine was built to replicate a late Ford Flathead engine (8BA). All the work was done on a manual mill and some lathes.

- The engine block and major components, heads, water pumps, oil pan, and bell housing were machined from 6061 aluminum.

- The crankshaft was made from 1144 stress-proof steel, and was made in one piece.

- The camshaft was made from W-1 drill rod.

- The connecting rods were made from steel with bronze bearing inserts.

- The heads, intake manifold, and waste pumps were all made in two sections to create internal water passages for cooling.

- The engine has a full pressure oil system, from the pump to the cam bearings to the mains, and then out to the individual rods.

- The oil pump and distributor are driven by helical gear sets, which George machined.

- The bore is .830 diameter, and the stroke is 1.125.

- The valve diameter is .416 with .094 diameter stems.

- The carburetors are an air-bleed type, machined to resemble Stromberg 97’s.

- The ignition is spark triggered by a Hall pickup, which is mounted on the side of the distributor.

- The radiator was hand fabricated from brass tubes, and plates with the top and bottom tanks milled from solid brass.

More photos of the finished engine can be seen in George’s photos. Also, you can watch this video of the engine with George explaining the various functions.

Over the years, George’s small tooling has grown. However, he still used the 6-inch Craftsman lathe, the Enco mill, and an added 11-inch Logan lathe for bigger parts. George thinks model engineering is one of the greatest hobbies going. He has enjoyed meeting and sharing information with all the great craftsmen and builders he’s encountered over the years.

Craftsman of the Year Winner for 2016

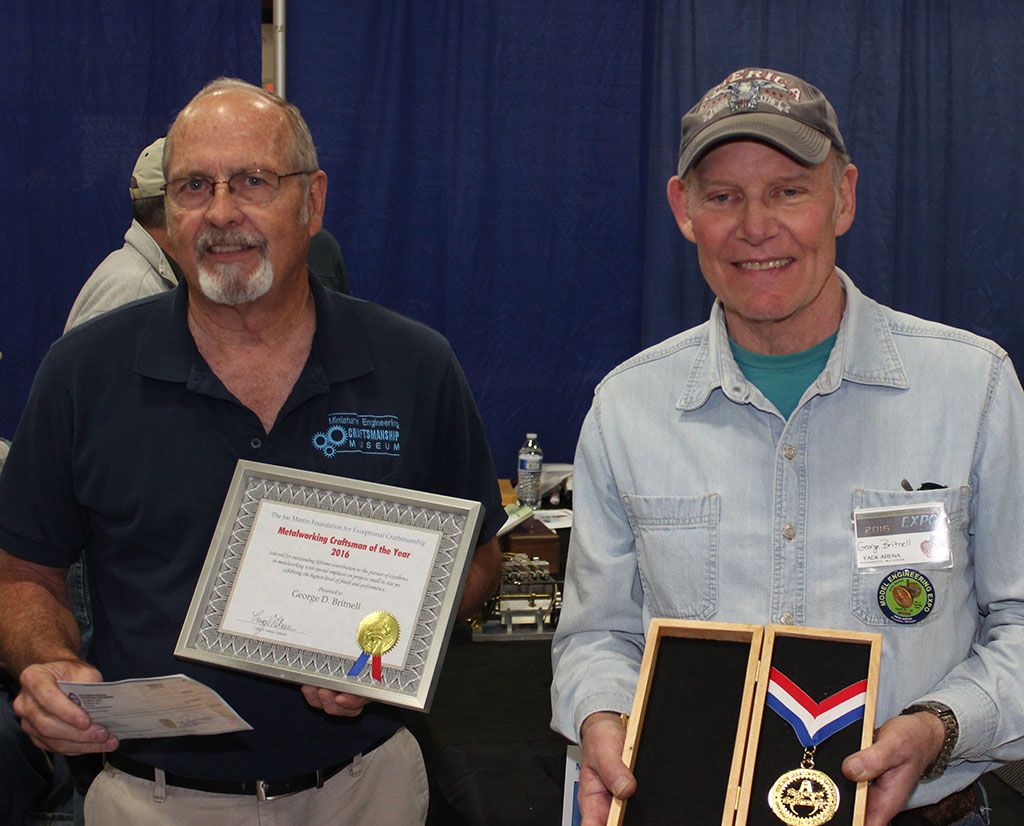

In 2016, George Britnell was selected by the Joe Martin Foundation as the 20th winner of our top annual award. He was presented with a check for $2000, a book on the foundation, an engraved gold medallion, and a certificate of appreciation at the North American Model Engineering Society Expo in Wyandotte, Michigan. George exhibited a wide selection of his models at the show, which took place in April of 2016.

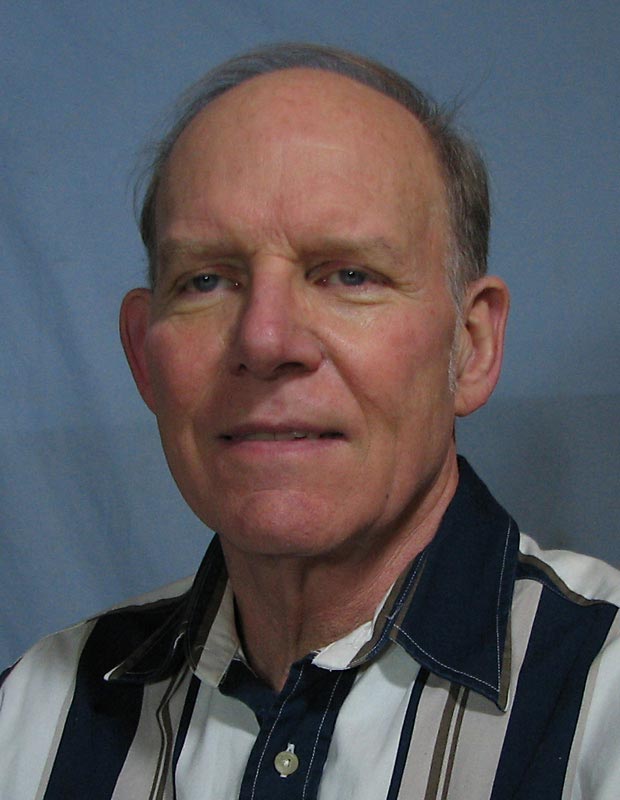

George Britnell (right) accepts his award as the Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year for 2016. He is holding an engraved medallion while former foundation director Craig Libuse (left) presents his certificate.

George’s Perspective on Craftsmanship

The Joe Martin Foundation welcomes the input of various craftsmen on the topic of what constitutes “craftsmanship” when considering the range of tools and technology available. George submitted the following thoughts on the topic:

“Having been formally trained as a metal patternmaker in the late 60’s and early 70’s, I was taught not only to use machine tools, but to use files, scrapers and radius gauges to bring the machined pieces to exacting tolerances. As the years went on, and CNC equipment was introduced to our shop, the hand finishing that in the past could have taken many hours and days to complete could now be produced by machine. Where once a person would have had to figure out how to get down into a pocket to blend it out, now the machine could be programmed to take minute cuts with a small cutter to replicate what the craftsman did.

I consider myself an ‘old school’ craftsman. Do I use CAD to help visualize my ideas and designs? Absolutely! Do I use machines to remove and shape metal into the desired shapes? Certainly! There’s no doubt that given enough time, a hammer, some sharp chisels and a file could produce things of beauty. Just look at the clocks, automatons and telescopes that were produced centuries ago—all with rudimentary tools.

George at the 2011 NAMES Expo in Detroit. He brought along the transmission he was working on for his Ford 300 Inline 6-cylinder engine.

There’s no doubt that [the ability to] design, and ultimately the process of producing a piece of art, are not gifts given to everyone. But I guess I have to draw the line, although somewhat vague, as to how the part being produced is finished. Let’s take a couple of examples to clarify my position. At one time, carved wood found in cabinetry and headboards was sculpted by hand. Today there aren’t many who could or would want to pay for that type of work; however, with CNC routers a part that might take weeks to carve can now be done in days. Can the finished piece be considered ‘craftsmanship’? Not really. To be sure though, it is still art.

Now, on to our interests: making miniatures, engines, guns and tools to name but a few. Could all the parts that comprise the indescribable work of Lou Chenot making the model Deusenberg have been made by machines in this day and age? There is no doubt. But would the finished product then be considered to have been made by a craftsman? Or was it just a machine doing what it was told to do?

I have seen countless examples of metal artistry through the years, with more and more of it being produced by CNC machines. There is nothing that can take away from the quality and exactness being produced by this process. But to me, working metal, wood and glass by hand is more befitting of the term ‘craftsman’.

You be the judge!

—George D. Britnell, 2013

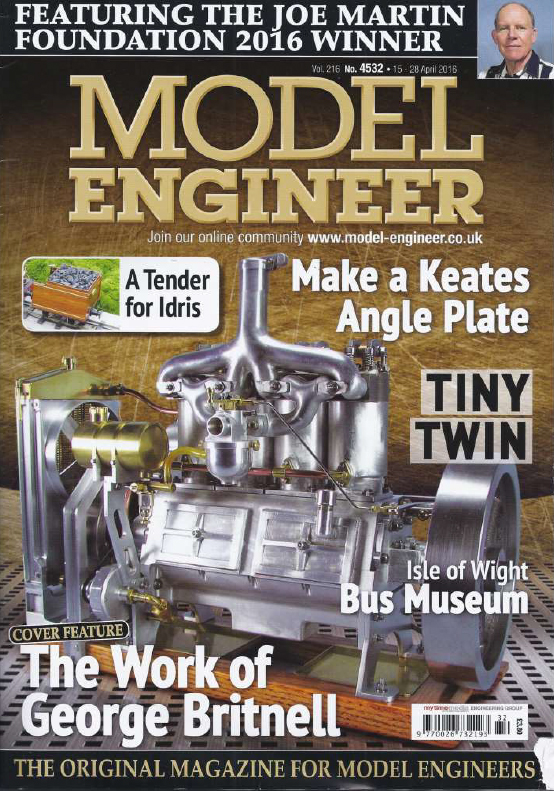

Magazine Articles About George Britnell

Model Engineer magazine ran an article in Vol 216, No. 4532, April 2016 featurning George’s award winning work.

Additionally, the second image shows the NAMES Expo program biography of George for the 2016 show. Click on images to enlarge.

View more photos of George’s masterful model engineering work, covering a wide range of projects.