Model Engineering That Includes a Complete 1910 Mercer T35 Raceabout in Miniature

An Introduction From Mr. Dahlberg Himself

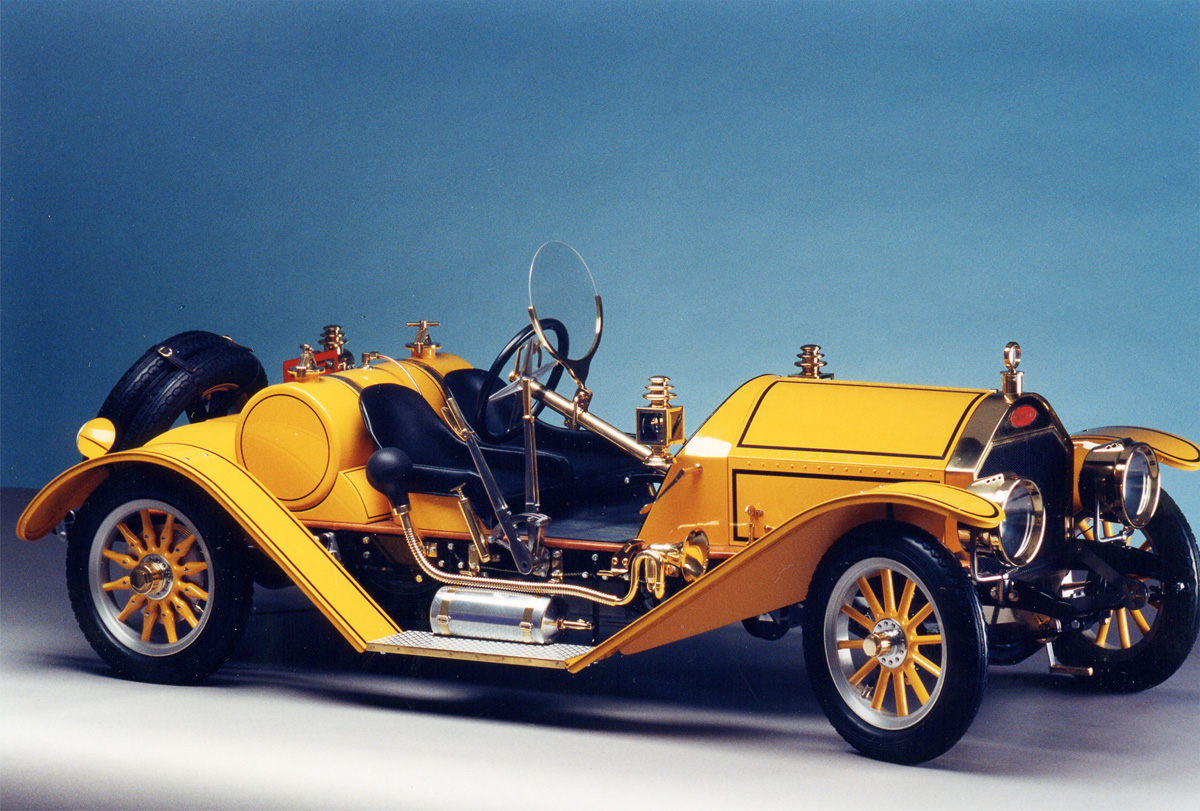

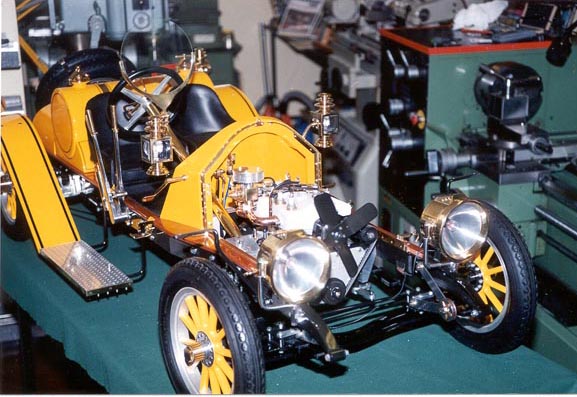

I have made a model of a car that is one of the most famous U.S. cars from the early twentieth century. This car is a 2/5 scale model of a U.S. road racer called the Mercer T35 Raceabout, from the year 1910.

In order to tell you some of my background, I taught mathematics, physics and chemistry for 40 years. I have taken a keen interest in mechanics since I was a boy, and I’ve been making models of internal combustion engines all my life. I started early, and made my first engine—a 2-stroke, 14 cc engine—61 years ago, when I was just fourteen years old. All my pupils studying physics have seen it run on the teacher’s desk.

Ten years ago (in 1997), I happened to set my eyes on a picture of the Mercer Raceabout in one of my son’s motoring books, and immediately decided to build a model of it. I have taken more than 500 pictures of the making of the model. On the last page of my website you will also find pictures of my 1/4 scale 9-cylinder Wright J-5 Radial Engine, and a 50-pound, 200 cc Supercharged V-8 Engine.

Although Ingvar Dahlberg has created other models, he became best known in model engineering circles for this 2/5 scale 1910 Mercer T35 Raceabout, which is complete to the very last detail.

My Mercer model is well known in Europe, as I have brought my models to five large exhibitions in England. These were in Donington, London, Harrogate, and twice to Bristol—as well as Sinsheim in Germany.

A lot of text and pictures have been published in magazines like Model Engineer, Engineering in Miniature (England), and Maschinen Im Modellbau (Germany). Last year (2006), the U.S. magazine Model Engine Builder published a centerfold picture, along with the story behind the car.

—Ingvar Dahlberg, Mariestad, Sweden

In addition to what he wrote in his introductory email to the museum, some of Mr. Dahlberg’s other work should be noted. In particular, Ingvar produced and sold kits and components for teaching elementary electronics in Swedish schools for over 30 years. He was still producing those kits at the time of this writing. This career allowed Ingvar to build the workshop which made his other wonderful projects possible.

In that workshop, Ingvar built a Stuart 4B steam engine, a Sea Lion IC engine designed by Edgar Westbury (designer of the museum’s own Seal Engine Project, and a Wright J-5 9-cylinder radial engine. Dahlberg and his son also completed a thorough restoration of a classic sports car—a 1949 MG-TC. His work on the full-size MG heavily influenced his approach to building the model Mercer, as both are based on a fundamentally simple design.

The 1949 MG-TC that was restored by Ingvar and his son.

Building the Mercer

Now, it all started when Ingvar Dahlberg saw a photo of the 1910 Mercer in one of his son’s books on vintage cars. He was immediately inspired to make one himself. The 70 kg miniature automobile would take five years to make, because other than the tires and spark plugs, Dahlberg had to make every part himself. As is often the case with such a project, the scale of the whole was dictated by the size of the first few parts that Dahlberg could find. In this case, Ingvar was able to locate several bicycle tires at a local shop that closely matched the look of the original tires used by Mercer. They were 12.5″ in diameter. The tire size dictated the 2/5 scale (or 40% according to Dahlberg) of the entire model. Ultimately, it would have a 106 cm wheelbase, and 56 cm track.

Since no plans for the car could be found, Dahlberg started with the photos in his sons book, and the tires he had already procured. He drew two circles of the proper size and center distance on a piece of paper, and proceeded to draw a side view of the car in the scale he would build it. Dahlberg also used the photos to draw other views of the car, scaling items from the pictures until he had views of every side drawn.

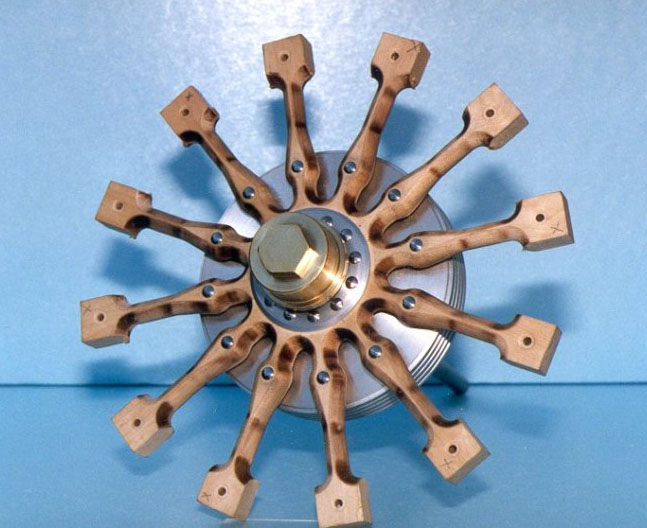

With six tires allocated, Dahlberg decided to start the construction process with the wheels. Patterns were made, and the rims were cast in light alloy. The wooden spokes (different front and rear, because of the brakes) were then cut from birch, using a radius mill and rotary table. Ingvar then went on to weld up the frame, and cast the front axle. He then built the springs, radiator, gearbox, rear differential, and fenders. The car was taking shape!

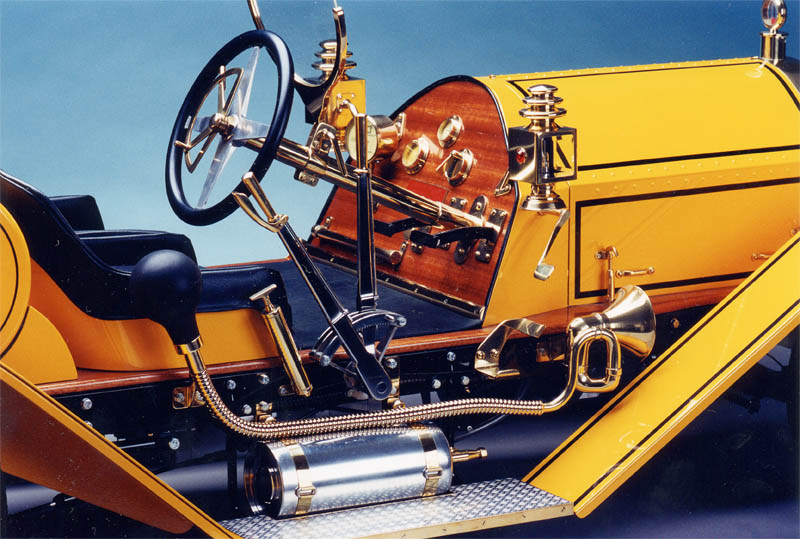

Next came the bodywork and dash. The brass running lights, dash instruments (non-functional), brake levers, and other detail elements required many different machining operations. For example, building the headlamp rim required a metal spinning process. The dash is made from mahogany. The brass rear license plate is etched with the words, “California Horseless Wagon.”

Since he started by purchasing the six tires, Ingvar decided to build the wheels first. He made a pattern, and cast the six rims in light alloy.

The clutch and gear case were designed around a radio control servo. This servo actuates the clutch to operate the forward and reverse gears. Though not a duplicate of the original internally, this was done to make the car functional in demonstrations. The differential case was based on the case for an electric motor found in a junkyard. Not trusting his gear cutting skills at the time, Dahlberg purchased the close-fitting internal gears, rather than making them. The end pieces and bushings were turned, and the driveline was complete.

An October, 1994 issue of Strictly IC magazine had plans for a 1/6 scale Simplex engine that closely resembled the original engine used in the Mercer. Ingvar couldn’t find any original engine plans that showed the internal workings, so the plans from Strictly IC were used as the best alternative. The original engine had a massive 5 liter displacement, which would have meant a 320 cc scale model. Not looking for any land speed records, Ingvar decided to reduce that to 120 cc.

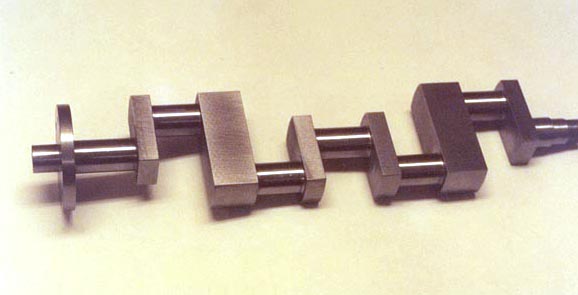

The crankshaft started as a 10 kg billet of steel, which was band-sawed to shape. It was eventually whittled down to 800 grams after many operations on the lathe and mill. Patterns were made for the upper and lower crankcase, plus the side cover. Then the parts were cast and machined in the mill. However, attempting to cast the engine block presented a problem. The Mercer did not have a separate cylinder head—it was made in one piece. This required the design and construction of a special 3-part molding flask, which Ingvar did in his own workshop.

Ingvar then took it to the foundry where the pour was done. The core was made from eleven sand-cast pieces glued together. After a few initial problems, block castings number 4 and 5 came out well, and the machining was begun. To make the valves, Ingvar turned some discarded ones he had found on a tank engine. These provided a proper mix of materials for the job, and were also easy to turn in the lathe.

Now, the steel and iron parts were bead-blasted. Then they were taken to a plant near Dahlberg’s home, where they were coated with a zinc-iron galvanizing. This had proven to be the best rust-proofing treatment that Ingvar could find. This process was used for 85 different parts, which were dipped in several baths and electroplating solutions.

Interestingly, Ingvar’s parts were going through this process alongside thousands of parts being made for the 1998 Volvo S70. However, the rust proofing treatment wasn’t the most interesting aspect of this process. When returning from the zinc-iron-bath, all of the parts were then dipped for three minutes in a chromium-bath. This bath gave the parts a deep and very smooth black color. Afterward, all the parts were sprayed with a two-component clear lacquer, leaving an excellent finish.

Moving on, Dahlberg constructed a camshaft grinder with some help from Robert Washburn, and the articles in Strictly IC. Ingvar ground his cams from SIS 2940-03 material (Swedish Standard), because it could be heat treated without distortion. The engine was a twin cam design, but Ingvar ground a third cam to showcase alongside the car. This was great for anyone interested in seeing how the engine was made. Construction of the cylinder blocks took one whole year, but the engine was finally ready for assembly. A dual ignition system was developed when the original Hall type system proved inadequate. The first successful run of the engine took place in May of 2001.

Mr. Dahlberg did all the paint spraying himself, starting with an etching primer for the aluminum parts. It took about three weeks to do the preliminary painting, but for the final finish he took the parts to a local professional painting company. They had a dust-free booth where the final finish was applied. This took just 25 minutes, but resulted in a perfect finish. The completed car is quite large at 5.5 feet long, and weighing 150 pounds.

After the paint job, the car was then fully assembled. Ingvar had actually never seen a real Mercer in person. But that changed after he completed his model. An American car collector, who had purchased a castle in England, learned of Ingvar’s Mercer through a fellow Swedish collector. The American had brought a real Mercer to England for vintage racing. In May of 2004, Ingvar was invited to go for a ride through the English countryside in the full-size, restored Mercer. It was very similar to his model, and the experience was quite a thrill.

At any rate, Ingvar now had his own version of the car of his dreams, which he could enjoy at any moment. At the time of this writing, Dahlberg was planning to partially disassemble the model so the engine could go back into the machine shop. He had plans for some improvements that would make the prized Mercer T35 Raceabout run even better!

Ingvar in a real Mercer. He finally got to take a ride in an original several years after building his model.

Ingvar Dahlberg’s Workshop

Ingvar Dahlberg’s well-equipped and well-lit shop is pictured below from several angles. Some of the photos show Ingvar alongside his miniature Mercer.

Other Projects by Mr. Dahlberg

It’s important to note that the Mercer is certainly not the only thing Mr. Dahlberg has ever built. The skills needed to build a complete car (of which there are many) were developed by Ingvar through various projects over the course of his life. Among his other projects, Ingvar built a 1/4 scale Wright J-5 9-cylinder radial aircraft engine, and a Westbury Sea Lion 4-cylinder. At the time of this writing, he was also nearing completion on a 200 cc supercharged V-8 engine. Dahlberg also became a member of “The Engine Builders,” a Swedish club. They held an annual informal meeting at the Swedish Gliding School at Ålleberg, near the city of Falköping. In truth, it was less of a club, and more of a collection of people interested in building engines. They gathered whenever possible for the simple fun of running and talking about engines—something Mr. Dahlberg is very well-versed in.

More information and photos covering the Mercer construction can be found on Mr. Dahlberg’s personal website. Ingvar has kindly given us permission to reproduce many of those photos here, and in his detailed photo section.