1927—January 30, 2017

An Aerospace Engineer Builds Award Winning Airplanes, Boats and Scale Model Machines

Introduction

Gerhard Spielmann was first introduced to us by former Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year winner Wilhelm Huxhold. Mr. Huxhold had encouraged Mr. Spielmann to enter his scale model Bridgeport mill in Sherline’s miniature machining contest at the North American Model Engineering Society expo in April 2003. Mr. Huxhold, a two-time former winner of the contest himself, was also entering a model in the competition. Ultimately, Mr. Spielmann’s model ended up winning first place in the contest, with Bill Huxhold’s entry taking second. However, Mr. Huxhold was pleased that his recommendation of the quality of Mr. Spielmann’s work had been vindicated by the contest results.

Biography

Gerhard Spielmann was born in Germany in 1927, and his family emigrated to the United States in 1928. While attending Brooklyn Tech, Gerhard’s after school hours were spent working with his father who was a goldsmith. During this period he was introduced to the art of fabricating jewelry and related items from precious metals.

After Gerhard graduated from school, he served in the military in the 82nd Airborne Division, 505th Parachute Regiment. Part of that assignment included building three-dimensional terrain models, which further added to his skills as a craftsman.

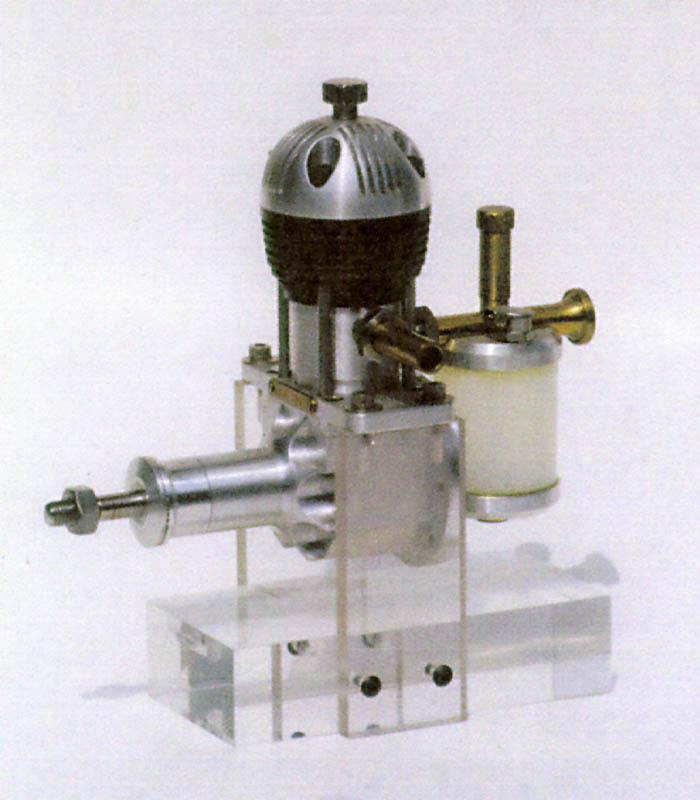

Gerhard’s MLA-17 Diesel engine was machined from cast iron and aluminum bar stock. The .19 cubic inch engine was built from a design by Andy Lofquist of “Metal Lathe Accessories.” Though Andy’s plans were excellent, Gerhard made slight modifications to improve the assembly, service and aesthetics. It ran well at 5,000 rpm, but since the diesel exhaust was messy, he rarely ran the engine.

Upon completion of his military service, Gerhard served a four-year apprenticeship as a tool and die maker at a watch case factory. It was here, under the tutelage of the “Meister,” that he learned the basics of quality machining and work ethic—attributes which he held in high esteem.

During the next fifteen years as a tool maker, Gerhard’s work involved making, blanking, drawing, and coining dies for watches and medical instruments. Toward the end of this time period, his employer and he formed a subsidiary partnership to set up and produce medical and optometrical test instruments.

While still employed as a toolmaker in 1960, Gerhard ran a small side business as a gunsmith, offering repair and custom gun work. In 1962, he started his own full-time business, Mid-Island Tool & Die Company. In 1964, Gerhard formed a partnership with his former employer and started Milard Precision Corp.

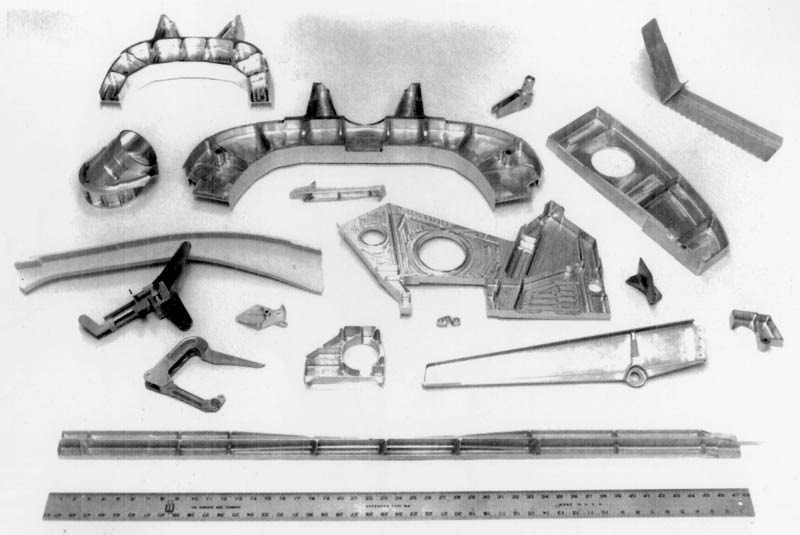

In 1965, he founded Phoenix Machine Products to do work in the aerospace field. This business built machined components for the Apollo program’s Lunar Excursion Module. Many of the parts that Gerhard crafted now reside on the moon’s surface, or are still in orbit!

This office display shows several aircraft parts made by Gerhard’s shop over the years. The parts were made for aircraft including the F-14, EA6B, E2C, and 747.

When the moon program was completed, Gerhard branched off into the military and commercial aircraft field. In 1982, he sold his business, which became Phoenix Machine Products of Hauppauge, Inc., and stayed on as head of quality engineering.

A year later the business became a part of The Charlco Group, and Gerhard became Vice President of Operations and General Manager. In 2003, he was still employed by that company as Vice President of Engineering on a part time basis.

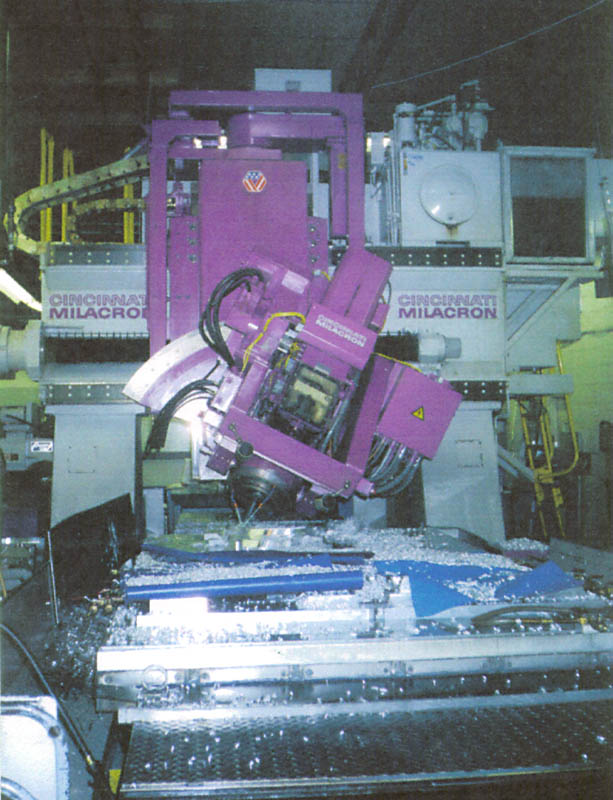

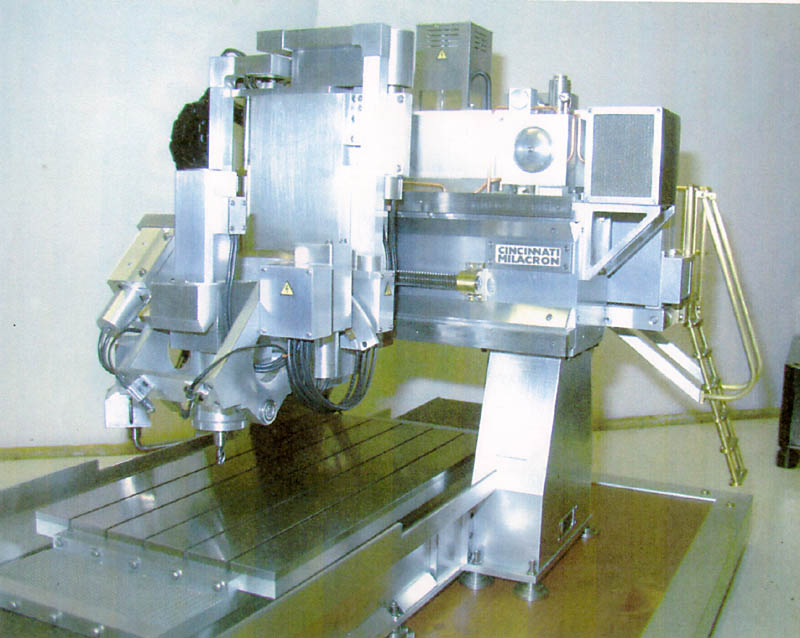

Although his position mainly involved advisory and technical assistance, Gerhard was instrumental in securing and manufacturing wing components and assemblies for the Boeing commercial airliners. The parts were manufactured on 3, 4, and 5-axis CNC milling machines—one of which was a Cincinnati 30-volt, 5-axis bridge mill. Gerhard chose to make a model of this machine in 1/18 scale, which can be seen below. (Every Boeing 777 and 767 wing has parts that were produced on this machine under Gerhard’s direction.)

This is a photo of the actual Cincinnati 30-volt, 5-axis machine that Gerhard used as a prototype for his model. This giant machine made aircraft parts at the plant where he worked as an engineering consultant, so Gerhard had access for photos and measurements.

Gerhard’s 1/18 scale model of the Cincinnati 30-volt, 5-axis machine. Gerhard’s model remains unpainted so you can see that no fillers or patches were used in its construction. This fully functional model moves on all the same axes as the full-size prototype, and can be controlled from a separate box using switches for each axis.

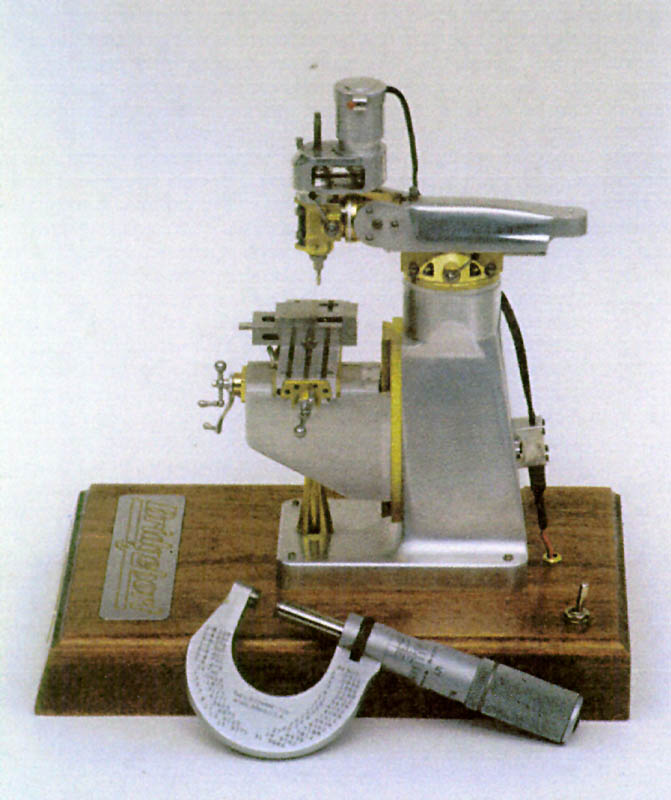

Fortunately, the part time employment arrangement gave Gerhard an opportunity to resume his passion for model building. He became involved in static and radio controlled ship and airplane models. After that, Gerhard’s interest turned to miniature machine tool models. His first tool model was the 1/12 scale Bridgeport “M Head” mill with shaper attachment. This was the model that won the Sherline contest. His second model was the 1/18 scale 5-axis milling machine.

Both of Gerhard’s model machines are electrically powered and fully operational. He also had plans to develop tooling and accessories for them. In addition to building flying aircraft models, Gerhard also earned a private pilot’s license for single engine aircraft in 1970. In 1999, he was given a Certificate of Recognition from the Cradle of Aviation Museum for his dedicated service, and contribution to the aerospace heritage of Long Island.

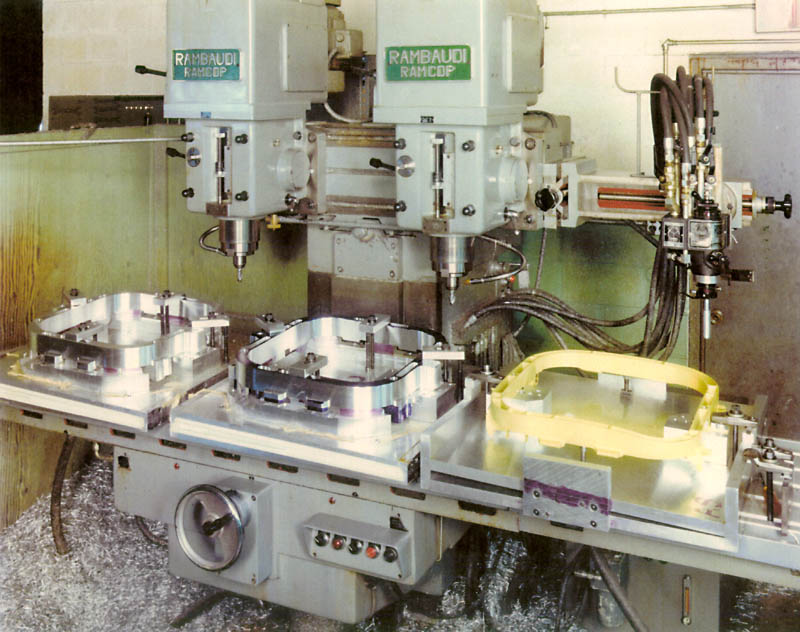

EC2 aircraft escape hatches being machined on a Rambaudi Ramcop hydraulic tracing mill. Prior to CNC machines, this was how precision production machining was done in 1975.

Mr. Spielmann’s Shop

Gerhard did his work in a 20′ x 30′ ground level basement adjacent to a 3-car garage. His power tools included: a 1/2 hp Bridgeport mill purchased new in 1962; a 9″ Southbend lathe rebuilt in 1980; a Swiss Schaublin bench lathe with 5C collet capacity; a butterfly die filer; a bandsaw; and related machine tool accessories. Gerhard’s hand tools consisted of the favorites that he had accumulated since his early days as a tool and die maker.

During his time in that trade, they did not have the luxury of EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining) equipment to make a blanking die. Nor did they have a 3D CNC mill to make a coining die. Gerhard was given a piece of tool steel and expected to produce a finished product using saws, files, engraving tools, and basic measuring tools. His collection of tools was both vast and varied. Gerhard was regularly asked, “What kind of tool is that and how is it used?”

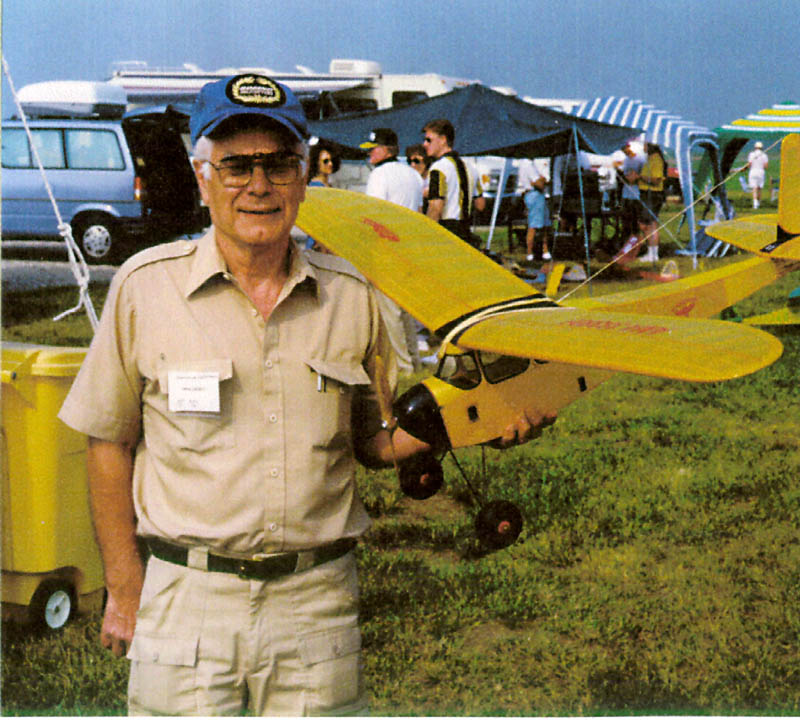

Gerhard holding his silk-covered vintage Viking RC airplane. He competed with this model in both the 618 and 620 classed at the Electric Nationals.

Advice From Gerhard Spielmann

Gerhard wrote the following about retirement: “Retirement, as per Webster’s dictionary, is defined as follows: ‘To withdraw oneself from business, active service or public life, especially because of advanced age.’ Since my ‘semi-retirement’ stage in life, I have been more active in the pursuit of my interests while still engaging in the world of manufacturing. To me, retirement is just a word in the dictionary. In my opinion, too many Americans are obsessed with the subject. We are becoming a society of sit-back-and-do-nothing retired people.”

On the topic of craftsmanship and productivity, Mr, Spielmann wrote, “In today’s ‘world economy’ we rarely find a product which has the label ‘Made in the USA.’ Unfortunately, we are losing the ability to craft or manufacture the products of which we were in the forefront. Are we placing more emphasis on liberal arts education rather than on subjects that relate to how to make something? I applaud the efforts of Sherline Products and the Joe Martin Foundation to foster our youth’s interest in the field of craftsmanship.”

Gerhard with his 1/8 scale model of the Fieseler Fi 156 Storch. This model won first place for “Best Technical Effort” at the 1998 KRC Electric Fly. It was powered by an Astro 25, geared on sixteen 1800 mAh cells, and had 715 square inches of wing area. The airplane was scratch-built without formal plans. Gerhard based his Storch on a 1/32″ plastic model, photos, and an original German service manual. It weighed just 112 ounces.

Gerhard’s advice for budding craftsmen: “Learn the basics. It’s not necessary to know that aluminum is derived from Bauxite; basics may start with the simple fact that a square corner is 90° and a circle has 360°. If the battery on your calculator dies, or your computer crashes, your recourse would be to go back to basic math and/or utilize your writing skills. Basics and desire go hand in hand. You may desire to make your own ice cream, but if you don’t know that milk is the prime ingredient, your desire will remain unsatisfied. A solid foundation or concept opens a world of possibilities, and we learn through our errors in any undertaking.”

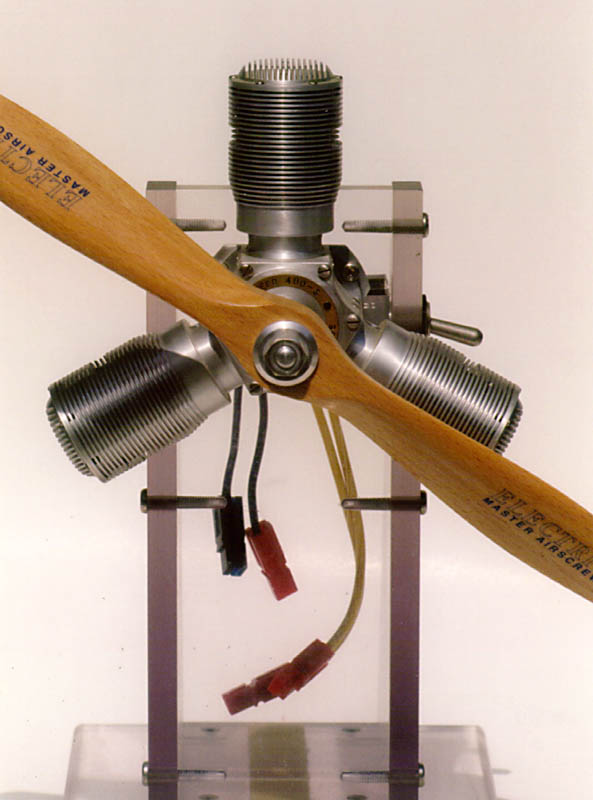

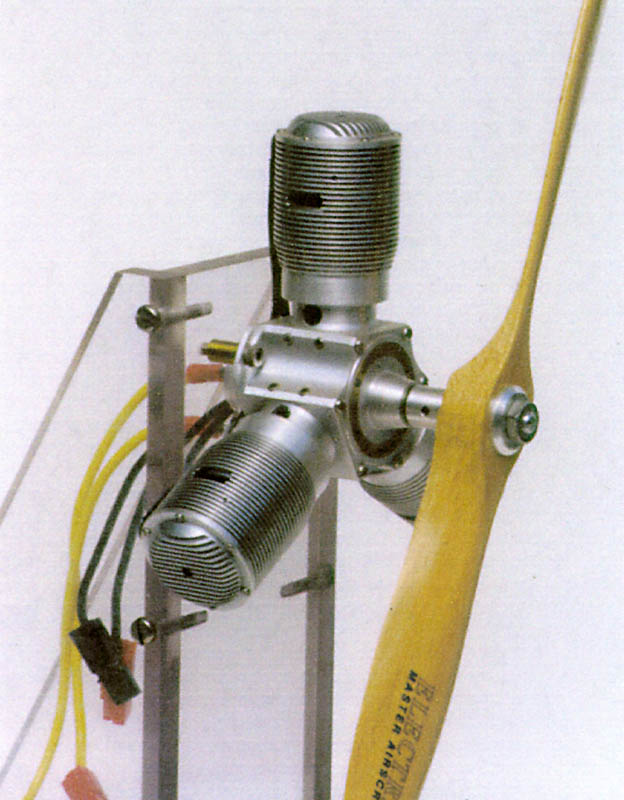

This interesting 3-cylinder radial aircraft engine model is actually an electric power plant designed to look like a traditional engine. Each cylinder has a 7.2-volt electric motor inside. These drive the central propeller shaft through bevel reduction gears with a 2:1 reduction.

Articles on Mr. Spielmann

Read a 1955 newspaper article about Mr. Spielmann and some of his early models.

View more photos of Gerhard Spielmann’s scale models.