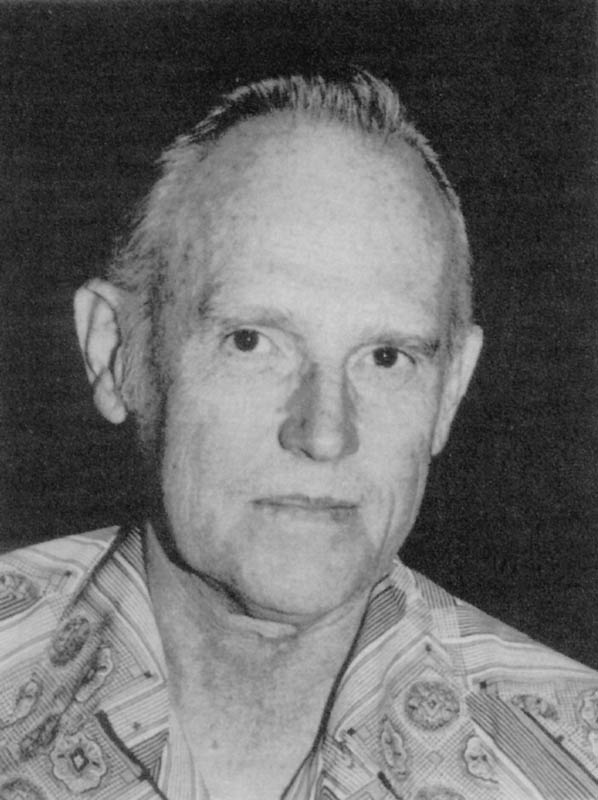

Expert Engine Tuner, Builder, and Technical Writer

Introduction

Clarence F. Lee started flying model airplanes and building his own engines in the late 1930’s. He designed several engines that set records and won championships. Clarence also designed engines that were produced for many years by companies like Veco and K&B. In later years, Clarence became even better known for his customization of racing engines for airplanes, cars, and boats. Not only would he rework the engines, but Clarence also regularly shared his expertise with those who preferred to do the work themselves.

Clarence was a familiar figure at car tracks, flying fields, and boat races along the West Coast. He was always willing to assist anyone having engine problems. Along with his own innovations in model engine design, Clarence kept abreast of engine development worldwide. He was well informed on fuel, lubricants, tuned pipes, propellers, and many other areas of model engine building.

Clarence had a wealth of knowledge across the field, and he shared his wisdom in a column titled, “Engine Clinic” which was published every month in RC Modeler magazine for over 25 years. The Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum is proud to honor Clarence Lee for his lifelong contributions to model engine building.

An Introduction to Clarence Lee and C.F. Lee Manufacturing Co.

From RC Modeler magazine, November 1996, by Don Dewey

Born in Los Angeles in 1923, Clarence Lee grew up and attended school in nearby Glendale, California. At the age of seven, he built his first “solid” model which was quickly followed by flying “stick” models. His entry into powered aircraft came in 1937 when he built a Megow Quaker Flash, working for a year at odd jobs in order to buy the knocked-down, unassembled 1938 Bunch Mighty Midget that would power it.

His second free-flight was a Modelcraft Miss Tiny powered by a Keener Brat .15. Clarence found the model to be badly underpowered, so he designed a 2/3-sized Miss Tiny, which then flew quite well with the Brat.

Actually, as Clarence remembers, the reduced size Miss Tiny flew well enough that he wore out the connecting rod! Since he was taking auto shop in high school at the time, he asked the shop instructor if he could make a new rod since the shop had a lathe and drill press.

The teacher agreed, and Clarence learned to operate a lathe—something that he found came quite naturally to him. After a couple of attempts he had a finished rod, and soon after began making parts and repairing engines for his modeling friends.

The Veco .61 engine that Clarence designed in 1959. Joe Martin bought this particular engine brand new, and it has remained in the foundation’s collection since.

Lee lived just a few miles from Grand Central Air Terminal where many historic flights took place. As a boy, he would stand outside the terminal fence, dreaming of becoming a pilot as he watched the Ford Trimotors and Curtiss Condors take off and land. A short distance away was an Army National Guard flying field where various military aircraft practiced their maneuvers, and Clarence decided then and there that he would become an Army Air Corps pilot.

While attending high school, Clarence worked part time for a Glendale Chevrolet dealer, first detailing cars, then, as his auto shop experience grew, installing new clutches, new rings, doing valve jobs, and eventually complete engine overhauls. Lee’s first car was a 1929 Model A Ford with a 1932 Model B engine. As he earned money, he installed a Winfield high compression head, a three-quarter race cam, an SR downdraft carburetor, and a Mallory distributor—a hot combination in those days!

When he could afford the gasoline, he would run the car through the timing traps at Muroc Dry Lake (now a part of Edwards Air Force Base flight facilities). His best time was 101-102 mph. To this day, as with model engines, Clarence has remained involved with automobile work, both as a hobby and professionally.

After graduating from high school in 1941, Clarence went to work for Vega Aircraft (then a division of Lockheed Aircraft), where he worked swing shift as a machinist. During the days, he attended Glendale Junior College in order to meet the two-year college requirement for joining the Army Air Corps. Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, that requirement was dropped for those who could pass an equivalency test. Clarence was sworn into the Army Air Corps as an aviation cadet trainee in December, 1942.

A Veco .35 R/C glow plug engine with the original box and instructions was donated to the Craftsmanship Museum by Joshua Vest. Designed by Clarence, the .35 cubic inch engine has a bore of .784” and a stroke of .725”. It weighs 7-1/5 ounces, and puts out .60 hp at 12,000 rpm. A 12-4 propeller was recommended for general use with this engine. It was manufactured by K&B Manufacturing in Downey, CA. The instruction sheet is dated July, 1969.

During flight school in Texas, Lee flew the PT-19, BT-13, AT-15 and AT-10, with his final ten hours in the B-25. Besides the aircraft mentioned, Clarence had flight time in a variety of military aircraft including the P-38 and P-51.

During flight training, Clarence was supposed to be training to fly the Martin B-26; however, upon his graduation in 1944, the aircraft was declared obsolete. Lee ended up being sent to the China, Burma and India theater. There he piloted C-47’s and C-46’s for a combat cargo group flying the “hump” (Himalayan Mountains) from Burma to various airfields in the Kunming area of China.

Clarence made a total of 67 hump crossings carrying bombs, aviation gasoline and Chinese troops. On JV day, his group was transferred to Shanghai, China, to take over the Kaigwan Air Base from the Japanese.

Clarence returned to the United States and was discharged from active duty in 1946, although he remained in the Army Air Corps Reserve for an additional 7-1/2 years. Lee currently holds a commercial pilot’s license with multi-engine and instrument ratings.

After his return to the U.S., Clarence married his wife, Peggy, who at the time had a small floral shop located in a local nursery. Inasmuch as many thousands of pilots had returned home from WWII a year before Lee, the commercial piloting jobs had all been filled. By cashing in some war bonds, the Lee’s managed to raise enough money to rent a larger building in the main part of Tujunga, California where they opened up a floral business, and where Clarence worked for several years.

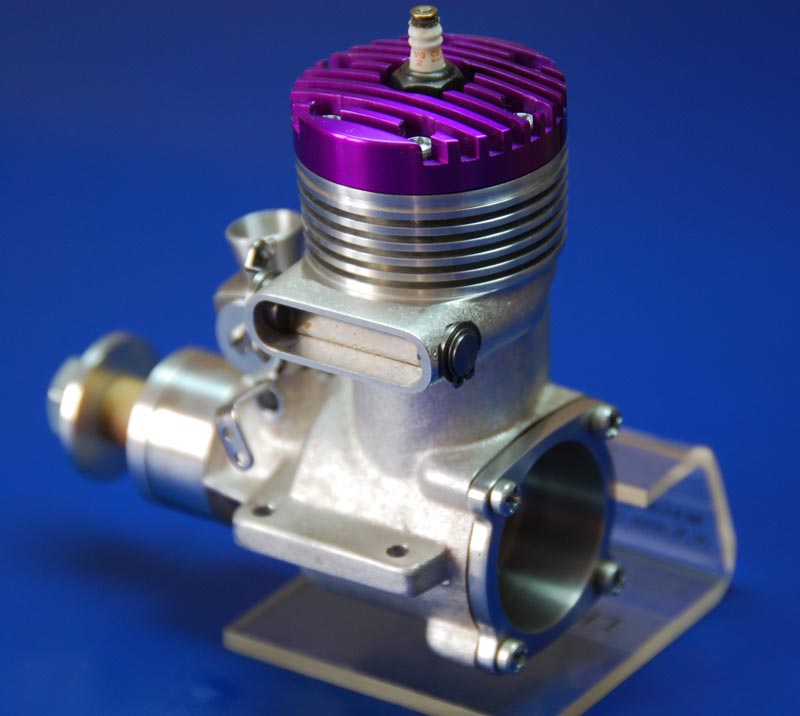

The Lee Sidewinder engine was an earlier project of Clarence’s. It was conceived to allow for smoother and tighter cowling in competition pattern models. The engine used bevel gears to transmit power to the prop. Although it was a good design, and the engine ran well, it was never put into production. Only three of these Sidewinders were ever made. (Photo courtesy of Peggy Lee.)

Clarence began flying control-line models while still in the service, and continued until 1956 when he became interested in radio control. One of his best control-line endeavors was placing third in Precision Aerobatics at the 1955 California Nationals, where he also captured third place in Proto Speed.

After taking up radio control, Clarence was somewhat unhappy with what was available in the way of engines for R/C use. As a result, in 1959 he designed and built his first Lee .45 engine designed strictly for R/C use. The engines were an instant success, and used by most of the top pattern fliers for numerous contest wins during that era. His own personal best was a first place win at the 1966 LARKS Open in Expert class. This event was the major West Coast contest of the year, drawing in excess of 120 entrants.

Clarence’s custom-made Lee engines carried a money-back guarantee if the purchaser was not happy with the performance. He never had anyone take him up on that guarantee! Following the success of the engine, he sold production rights to Veco Products, and a redesigned version became the Veco .45.

Lee was then commissioned by Veco to design a new ball bearing version of the original Veco .19 designed by Mel Anderson. Parts for four prototype engines were made, and the first production engines released in September of 1964. Clarence kept serial #001 and well-known West Coast flier, Dale Nutter got #002. Dale went on to set a new AMA Pylon speed record with the engine.

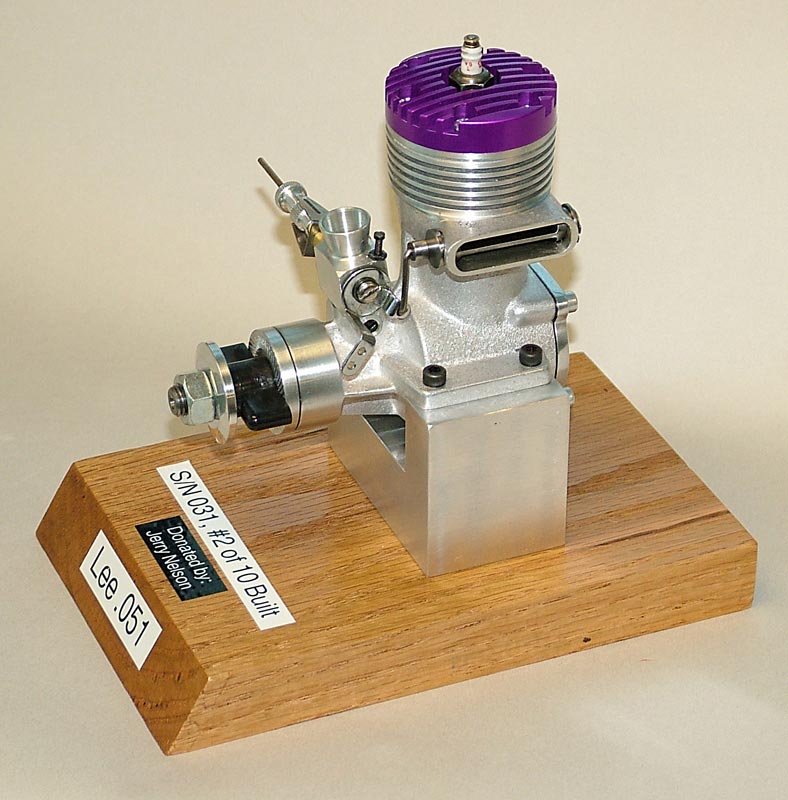

One of the ten hand-built Lee .51 engines was donated to the Joe Martin Foundation by Jerry Nelson in 2009. The serial number is #031, the 31st engine that Clarence built, and the second .051 he made—keeping the first for himself.

Lee was then commissioned by Veco to design a .61 size engine. With his past experience with the .45 and .19, he knew what he wanted in the way of a crankcase. So they went directly to the die-cast case without building sand-cast prototypes.

While the dies were being made, Clarence made the crankshafts, pistons, sleeves and remaining parts. Parts for six prototype engines were made, with five engines being assembled and the sixth saved for replacement parts. Serial #001 of the new Veco .61 was given to Cliff Weirick in July 1965, and Cliff went on to win the AMA Nationals with it that same year.

The next Veco commission for Clarence was to design and build a new ball bearing .35 engine following the basic design of the .19, .45, and .61. Three prototypes were built, with one of them going to a control-line speed flier, Gene Leedy.

Gene subsequently set a new Class B Proto Speed record with that engine. Unfortunately, the engine never went into production since Henry Engineering, the parent company of Veco Products, decided to drop the model engine business. They would instead concentrate on their manufacturing of aircraft seats, since the airlines were in the process of developing the first wide-bodied commercial airliners.

Clarence competed in R/C competition pattern events for about ten years until he became tired of the constant practice required. Not one to give up on competition, however, he entered the then new Formula I Pylon racing event, first racing as a team with his good friend, Wayne Wainwright, and later as a team with his own son, Jack Lee.

This is the same Lee .51 engine pictured above after Clarence himself restored it in May, 2009. Read his letter regarding the history of this engine.

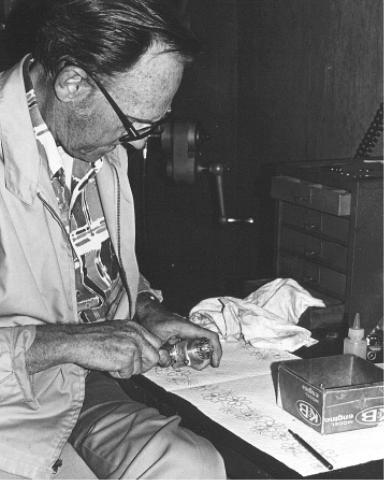

Today, Clarence laughingly refers to himself as semi-retired, although he hasn’t yet found a way to take things easier. In fact, busier than ever, Lee’s model engine business is now a full-time operation, as he sells custom fit versions of engines in the K&B line. Having sold many thousands of engines over the years, the servicing and repairing of these engines is almost a full-time operation in itself. Clarence admits that he continues the model engine business mainly to keep active, never having been a person who could sit back and do nothing.

Clarence holds AMA #2579 and was inducted into the Academy’s Hall Of Fame in 1983. He is a member of the National Miniature Pylon Racing Association, the Valley Flyers R/C Club, and the Model Engine Collector’s Association. Also a ham radio operator, Clarence’s ham call is WB6SAF.

Clarence’s column, “Engine Clinic,” has appeared in every monthly issue of RCM since January, 1969. His column has been immensely popular with the magazine’s readers since its inception, and it has always ranked among the top three in every reader interest survey conducted by the magazine. And, without fear of contradiction, I believe that most of us have learned most of what we know about the R/C engine from Clarence Lee. His personable type of writing, combined with his vast knowledge of his subject material has made him one of the sport’s most valuable assets.

— Don Dewey, November 1996

The Lee .49 engine as seen from the right front side. As Tim Dannels of the Model Engine Collector’s Journal noted, “These engines were the actual predecessors to the Series 200 line of Veco engines. Clarence was doing R&D work for Veco, and built a series of .45, .49, and .51 engines on the side. For those lucky enough to buy one, they were the best R/C engine in that size range in the air at the time. Performance was flawless.” (Photo courtesy of Tim Dannels.)

Another view of the Lee .49 from the left rear. Only 23 of the Lee .45 engines were built, despite orders for many more. They were just too time consuming to make. There were only six .49’s built, one of which is pictured here. In addition to those, Clarence also built seven .51 engines. That accounts for the total production of the Lee hand-built engines. (Photo courtesy of Tim Dannels.)

On July 1, 2005 Clarence added the following note about his engines:

“I built two experimental long stroke 49’s. Then, after I had given up making the engines, a group from Mexico up here for the Nats asked me what it would cost to make them an engine, as they had destroyed the one they had. I quoted $225.00 (original price was $75.00) and they ordered six. I was then swamped with orders from others. I decided to make the new engines 51’s, but had a few 45 crankshafts on hand, so decided to make the 51 piston/sleeves first, and then use these in conjunction with the 45 cranks for a 49.”

“I made four of these which, with the two long stroke 49’s, made six. One of the long stroke 49’s went to Bob Dunham. As it required an 8-ounce fuel tank, Bob thought this would throw off the balance of his Astro Hog, so I converted it back to a 45 so he could use a 6-ounce tank. I built 10 more 51s before quitting production for a total of 42 engines in all. So there you have a little more history.”

— Clarence Lee

Danny Claes of Belgium owns one of the Lee .51 engines. In fact, this was the last model made. (Photo courtesy of Danny Claes.)

Additionally, read an article that Clarence wrote about the Fitzpatrick .61 ABC engine.

View more photos of Clarence Lee’s racing engines.