A Ship Modeler Since Childhood

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2019

James Hastings (left) receiving his award for the Joe Martin Foundation’s Craftsman of the Year. The award was presented by Craig Libuse (right) on February 13, 2019, at the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum. Members of the board of directors attended the award ceremony, where Mr. Hastings gave a short presentation on how he constructs a “ship’s boat.” James was kind enough to donate a model ship he’d made, along with the solid wooden form he used to bend the ribs and planks.

Introduction

When craftsmen of the caliber of Jerry Kieffer and Roger Ronnie (both winners of the foundation’s highest award for craftsmanship) recommend looking into the work of a particular model maker, you do just that. After the Black Hills Model Engineering Show in 2009, Craig Libuse asked both Kieffer and Ronnie for input. Craig wanted to know if either of them had seen any work recently that the museum should be aware of. Both craftsmen mentioned the ship models made by James Hastings. Below, James tells in his own words how he got started, and offers valuable advice for craftsmen in his conclusion. His story is typical of some of our featured craftsmen in that James went from assembling kits to building each part by hand—all in the quest to make each model better than the last.

Growing up With Model Building

By James Hastings

I don’t recall any particular time when I decided that building wooden sailing ship models would become my lifelong hobby, or at least no “road to Damascus” moment. I just sort of drifted into it. My father, and his father before him, were ships engineers, which may explain the salt water in my arteries. But they were engineers first and foremost, and I’m sure they never went to sea in a wind powered ship in their lives. As a child growing up in New Jersey during World War II, my friends and I built models of planes, ships, race cars, tanks, trains—anything the local hobby shop had for sale that we could afford. A few of my early efforts were sailing ships, but I didn’t notice any addiction taking effect. Apparently it had.

When I was about 13, as a Christmas present, my parents gave me my first serious ship model kit. It was put out by the now defunct Marine Model Company. I gave it my best shot, and remember how proud I was of it. Fortunately, it no longer exists. As the years went by, I built several more of their kits.

After college, I was faced with the military draft and went into the US Air Force, surprising myself by staying in for a twenty-year career. Since frequent transfers, and a living-out-of-a-duffel-bag existence aren’t conducive to a ship modeling hobby, things were put on hold for several years. Then, recently married and transferred to Whiteman AFB, Missouri, as a missile launch officer, it seemed that I might stay put for awhile.

So, I packed up the unfinished model I had started in college and brought it with me to finish. This led to another, and another, and so on. But I noticed a growing dissatisfaction with kits in general. I found myself replacing the kit fittings with things I made myself, and buying books about the ships I was working on so I could verify some of the questionable instructions. In the hobby, this is known as kit bashing, and, unchecked, it leads to scratch-building.

Graduating From Kits to Scratch-Built Models

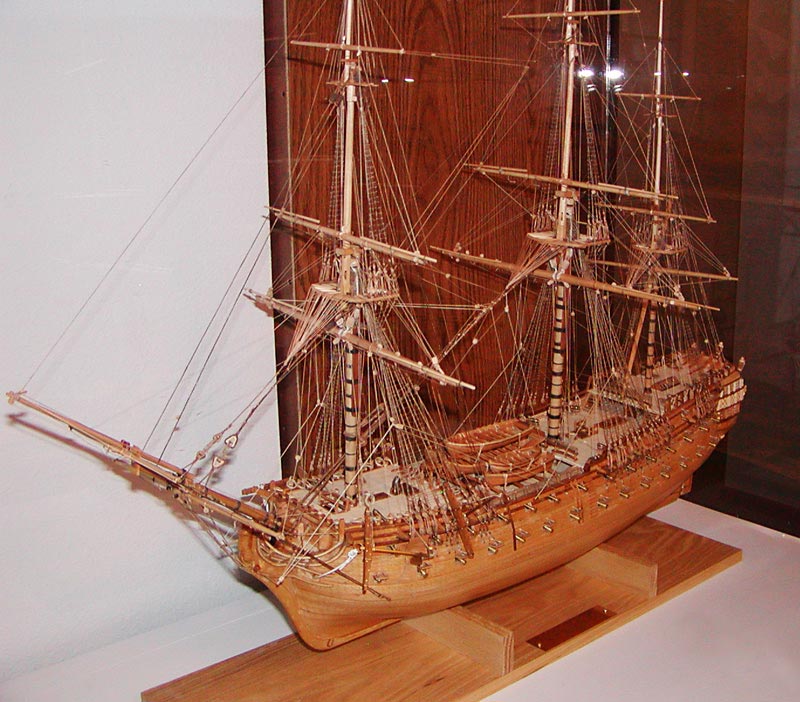

In 1972, recently transferred to Grand Forks AFB, North Dakota, I decided to take the scratch-building plunge, and bought Harold Underhill’s two volume work, “Plank-on-Frame Models.” This was a fortunate choice. Simply stated, I know of no better introduction to ship model building at this level. He taught me a great many things I didn’t know, and more importantly, a great many things I didn’t know I didn’t know.

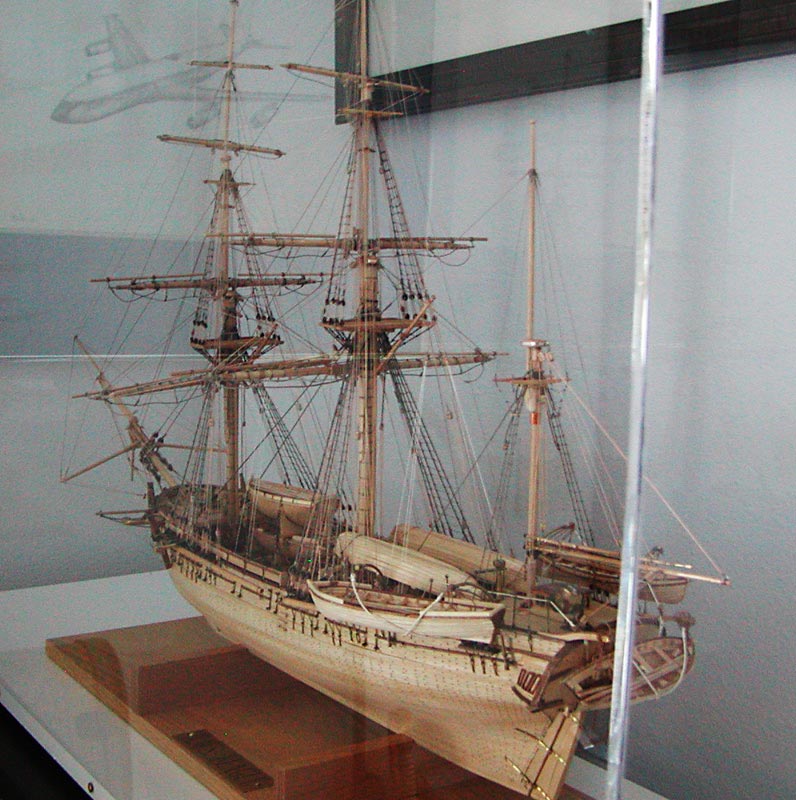

The volumes take you through the building of a model of a Norwegian brigantine named Leon. Among other things, the book covers: deriving from the line drawings the shape of each individual frame in the hull, how the frames were built up piece by piece, techniques of planking, and details of rigging that I never would have learned from kit building. By the time this project was finished, I was unashamedly hooked on scratch-building, and have never looked back. I was ready for anything.

Transferred again, this time to Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota, I decided to go for the gold. Longridge’s book, “The Anatomy of Nelson’s Ships,” is comparable to Underhill’s, but for the 100-gun, three-decker HMS Victory—Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Five and a half years later, it was finished. Since then, and having retired from the Air Force, it has been a story of one ship model after another. Harold Underhill wrote several other books with excellent drawings of sailing ships, especially those built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are a number of books published in the “Anatomy of the Ship” series, each one devoted to the construction of a model of a particular ship. I have done a number of these, with emphasis on the wooden sailing ships of the 18th and 19th centuries, which have always been my favorites.

Mr. Hastings (left) presenting a model of the Windjammer Barefoot Cruise Ship, Mandalay, to the ship’s Captain, Matt Thomas (right). James gifted the model to Mr. Thomas, and built it based on data he’d collected during his own 2003 voyage aboard this ship. He certainly knows how to get in good with the captain!

Tools for Woodworking in Miniature

I am sometimes asked what tools are required for scratch ship model building. Since a great deal of the work is very small-scale carpentry, basic woodworking power tools are a good place to start, with the emphasis on small size. I do have a standard size bandsaw for ripping thin planks off billets of hard wood, but my circular saws both take a blade only 4 inches in diameter. One table saw even has a micrometer attachment. My thickness sander is comparable in size.

I have two lathes: one of standard size, for turning masts and spars; and the other a Sherline for the small things, both wood and metal. Dremel makes a number of small power tools which are nearly indispensable. In the way of hand tools, there are probably no surprises: X-Acto knives; small hand saws; small vises; many styles of tweezers; many styles of clamps; and, if your eyes are getting as old as mine, some magnification capability is nice to have.

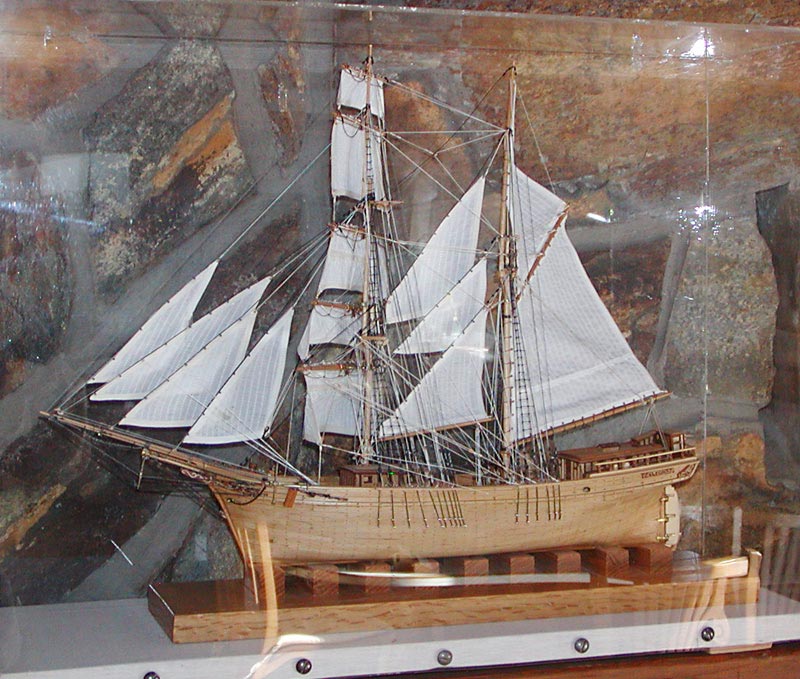

James’ scale model of the HMS Beagle. This ship was home to Charles Darwin during the voyage that led to his conception of the theory of evolution. (1818-1870.)

Frequently Asked Questions

People viewing my models have a number of questions for me, and they tend to get a bit repetitive. I am often asked how many hours of work it takes to build one of these ships. I tell them none. When they react questioningly to this, I add that there is no work involved. A great many hours of pleasure, to be sure, but no work. Then I add that I have a great many tools in my shop, but I do not have a clock.

I am also asked from time to time what is the hardest part of this hobby; is it the framing, or the planking, or the rigging? Well, it’s none of these things, although they do have their moments. The hardest part is to look at something you have worked on for a considerable time, see it in the cold light of dawn, and realize that either: (1) that is not how they built things in that time period; or (2) quality-wise, what you have just done is the dog’s breakfast.

Then, you have no choice but to either fix it or replace it, and it may well take days—or weeks—to get back to where you thought you were. This is the hardest part by far. However, if you don’t do this, every time you walk by your finished model, it will whisper to you. It will say something like, “Boy, you sure made a mess out of my rudder,” or “Why didn’t you fix my after deck house when you had the chance?” While there is no such thing as perfection in this hobby, one should always strive to do the best work they are capable of doing at that point in their development.

View more photos of James Hastings’ marvelous, award-winning model ships.