A Career Built on Car Models as Presentation Trophies for Race Car Drivers

Exceptional Results Based on a Father’s Advice

Submitted by Michael Dunlap

My father was a fighter pilot in World War II. He flew P-47’s and P-51’s. He remained passionate about those and other WWII aircraft for the rest of his life. I can still remember sitting at our kitchen table watching him build plastic models of those planes. He was so slow at trimming the pieces, painting them, and gluing them together. It seemed like it took forever to build a single model, but when they were done they looked as though they could really fly. I remember him saying to me, “Patience will produce a much more satisfying result.”

By the time I was ten, I had already assembled a number of airplane kits of my own. By twelve I had begun building model cars. The first was a model of a 1957 Thunderbird. Besides being a cool looking car, this was a model of something I could really identify with, because you could see a real one on the street most any day.

Around age fourteen, I remember stopping by a friend’s house so we could walk to school together. This particular morning he came out of his house carrying something wrapped in a towel. When he uncovered it and showed it to me, I was stunned. I still remember thinking, “This is the coolest thing I have ever seen!” It was a model of an early thirties vintage Ford body, just the firewall, doors and trunk—no fenders or engine cover. It had been hand carved and sanded from a solid block of balsa wood so that the body thickness was quite thin. It was so delicate and yet so well shaped, so perfect, I thought. I wondered how he had managed this feat. He said he was going to build a Hot Rod like one he had seen in a magazine. It made quite an impression on me.

From Kits to Building Models From Scratch

Prior to that day, I had never considered building a model from scratch. In fact, I didn’t build any scratch-built models until many years later. However, from that moment on, my enthusiasm for assembling kits by the instructions was greatly diminished. So I began customizing my models. At first, I simply exchanged parts from different kits. Soon I was chopping windshields, radiusing wheel wells, and piecing parts of different bodies together. The last plastic kit model I built began as a 1963 Corvette, and evolved into something a great deal more radical. It turned out to be more of a skills exercise than anything else, and while it wasn’t the most pleasing of designs, it was my own creation.

Over the next ten years, I had a number of jobs, and even started a business of my own, but none of them could hold my attention for long. Most of my spare time was spent making minor modifications to the numerous cars I owned, and driving them too darned fast. At the same time, I was becoming increasingly interested in auto racing, especially with the appearance of CART (Championship Auto Racing Teams), which promoted a full series of open wheel road course racing events in America.

Wire Models Lead to a First Professional Sale and a New Career

At the age of 28, I found myself with a lot of spare time on my hands. My fascination with miniatures had only intensified over the years, and I still remembered quite clearly my initial impression of my friend’s scratch-built balsa wood model. So I decided to begin building models again as a hobby, but this time I would build them from scratch, rather than kits.

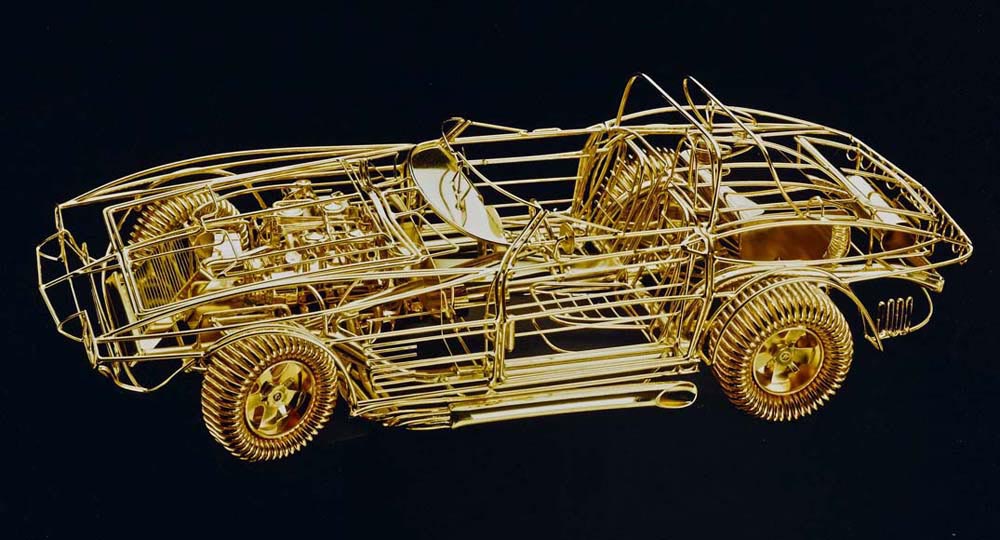

I had recently seen a 5-foot long model of the Hindenburg Blimp, which was built completely from thin copper wire. I adapted this technique to automobiles and was off to the races. My first model was a 1954 Corvette. The next was a 1978 Corvette. These were simple models, built using 12 and 14 gauge copper wire to represent the body styling and parting lines, as well as the tires. They were built strictly from photos I found in books and brochures, giving attention to proportion, but not to scale.

The issue of scale would be addressed while designing the next model, which was to be patterned after my own car, a 1973 Corvette. I worked in 1/12 scale because it was easy to convert feet to inches. It also gave the model enough size that the wire didn’t look too bulky, and yet had enough strength to retain its shape when handled. The only tools I had were a 4″ riveting hammer that had been passed down from my grandfather to my father to me (and I still use it every day), an old pair of needle nose pliers, a propane torch, and several fairly dull metal files.

Without realizing it, I had just embarked on a new career, doing the very thing I enjoyed most as a young boy. Eager to get a second opinion on my newly rediscovered hobby, I took them to show to a friend, Bob Schuler, who owned a thriving car customizing business called American Custom. He liked them enough to put them in a display case in his showroom, and within two weeks had sold them to his customers. He immediately ordered a couple more models of a limited edition Corvette (the Duntov Turbo) that he was building, with the approval of GM, to honor the accomplishments of Zora Arkus-Duntov—generally referred to as “The Father of the Corvette.”

Over the next year or so, we sold another couple dozen models of various corvettes through his shop before other clients began commissioning me to build models of their cars. It was a blast making model cars, and then having people like them enough to buy them. That’s when I began thinking that, with a little promotion, this could actually become a business. However, I kept my day job for a while longer.

Meeting the Right Photographer Leads To Contacts in the Big Leagues of Racing

The following year, I began searching for a photographer to help me produce a brochure to advertise my models. I finally located one who just happened to be the official photographer that year for the CART Racing Series. A few introductions later, and I was building models of Indy Cars. Shortly thereafter, a waiting list of clients developed which still continues to this day.

I have built model cars throughout most of my life. In the beginning it was because my dad did. Later, I built them in pursuit of my own interests. Since 1980, I have built models as a career. I’m continually amazed when I reflect on my good fortune, and I’m grateful for the people and events which have influenced my life. One of the most rewarding benefits has been working out of my home. This has kept me close and involved in the lives of my two sons, Rick and Tom, while my wife, Sue, has been required to travel extensively throughout her career.

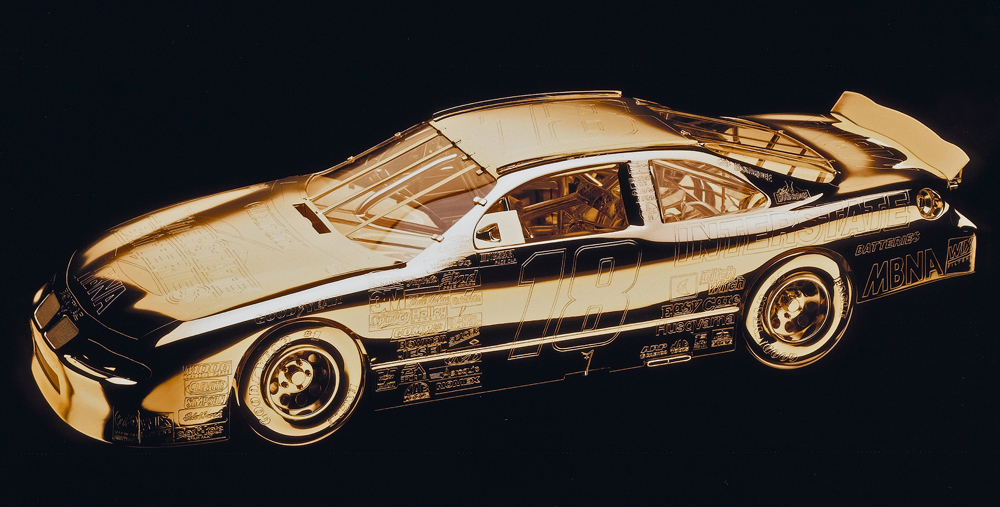

A young Mike Dunlap (center) holds one of his cars, which is being presented by Tom Monahan to Rick Mears for winning the 1983 CART Triple Crown. For over 20 years, Mike has built a Goodyear Gold Car Award, which is presented annually to the winner of the NASCAR Nextel Cup Championship.

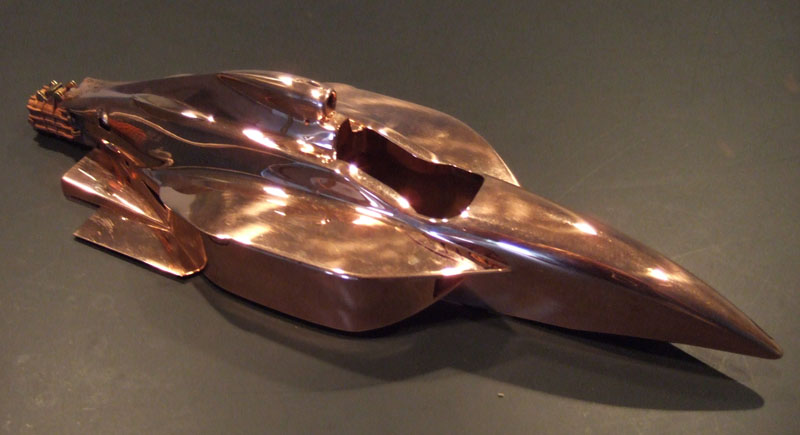

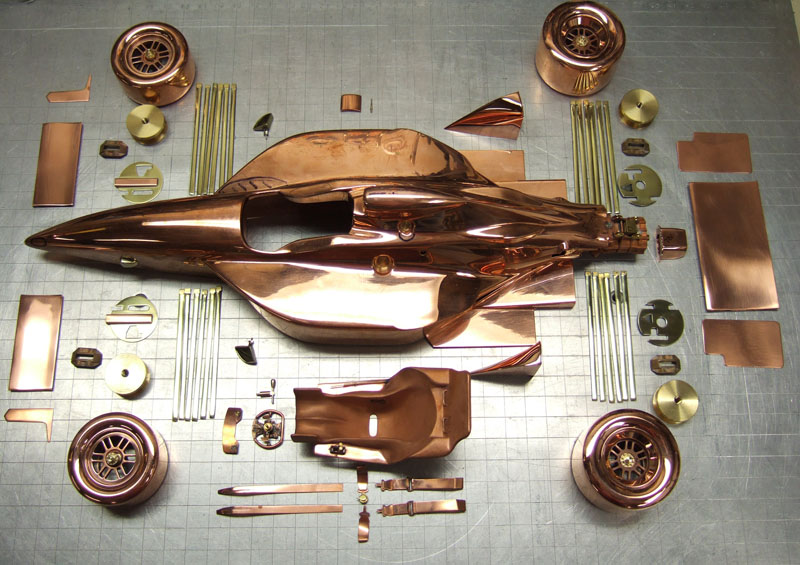

How the Car Bodies Are Formed

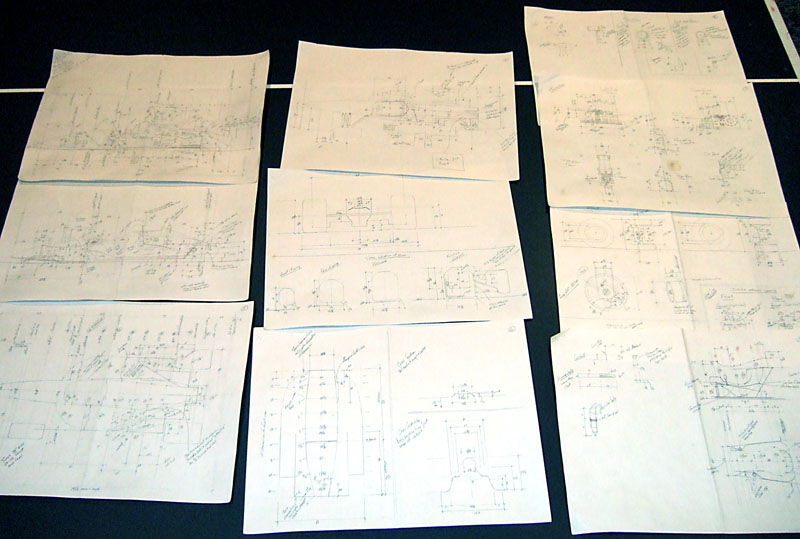

The process begins much the same as it did back when I built the model of my 1973 Corvette. I go to the actual car to be modeled, and take hundreds of measurements from which I produce a set of 1/12 scale drawings. Then I shoot over 300 photos, mostly detail shots.

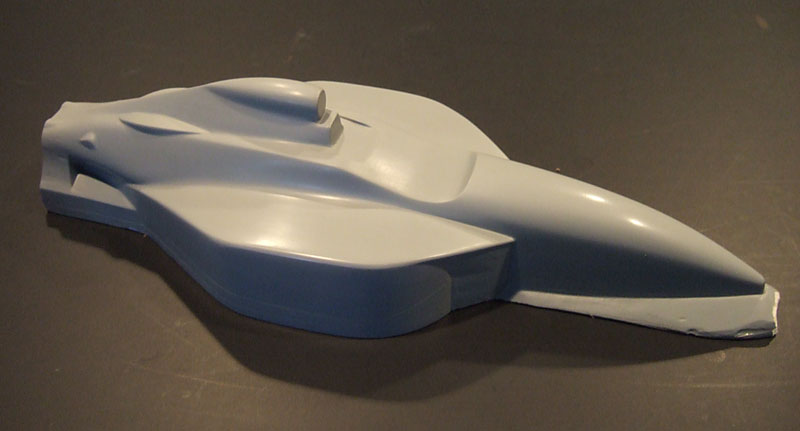

Back at my shop, I begin by sculpting a master model of the car’s body, from which I’ll make a mold. This model is made of plaster, although in the past I have made them from both wood and clay. The model is surfaced by painting with 15 to 20 coats of lacquer, sanding between each until a smooth finish coat is achieved.

This master is then fixed inside a Plexiglas mold box. The resulting space around the model is filled with polyurethane rubber, and left to cure. The box is then disassembled, and the master removed from the rubber mold, revealing a reverse image of the master model.

Next, I cut, fabricate, file, sand, and buff until I have a nice finished part ready for engraving. Since I build primarily race car models, a complete set of decals is required so that the engraver can reduce the patterns to 1/12 scale. He then has to position them correctly on the body, tires, and many other parts to be engraved. After cutting them into the metal, the parts are again buffed and polished, before going to the plating company where 24 karat gold is applied. Of course, this whole process is a bit more involved than a few sentences can describe, but you get the idea. (For more information on the outside contractors used, visit my website.)

I haven’t always used the above described methods to produce the bodies. Different problems over the years have required different solutions ranging from metal stretching, casting, and good old fashioned metalsmithing. In fact, I still use each of these processes from time to time. The constant drive for more efficient methods, and thus better reproductions, is the overriding motivator that keeps me interested in modeling. Even when a commission calls for two models of the same car, I use what I learn from the first to refine the second. It’s just instinctive to want to improve each part and each model.

Purchasing New Machine Tools Renews Inspiration

To this end, I’ve been adding new equipment to my shop for a while. Four years ago, a friend of mine, Augie Hiscano, suggested I replace my old jeweler’s lathe with a Sherline lathe. I researched the idea, and concluded that Augie was right. I purchased a Sherline model 4400 shortly thereafter. This single piece of equipment made a huge improvement in my ability to produce high quality parts.

This was the proverbial breath of fresh air that I needed to take my models to the next level. Just recently, I also purchased the Sherline 2000 CNC Milling Machine. While I’m just becoming acquainted with its capabilities, it has already enabled me to make improvements on the model currently on my bench.

Mike at work in his shop on a milling machine (left) and a lathe (right). At the time of this writing, he was tackling the learning curve of CNC, having decided he needed to bring these jobs in-house, rather than depending on others for complicated 3D machined parts. While good tools won’t turn a hack into a great craftsman, once a good craftsman reaches a certain level of skill, the only way to achieve better results is with better tools.

Updating my shop with new equipment has a double benefit. I can make more accurate reproductions, and I can make them faster. Since I work by commission, I must produce one-off originals on a schedule dictated by my clients. For example, each year the Goodyear Tire Company (a client for the past 21 years) presents the NASCAR Nextel Cup Champion with a gold model of their actual race car. Without a crystal ball in hand, that means they will need one of the three body types (Chevy, Dodge, or Ford) for the trophy.

The model must be detailed, inside and out, exactly as the real car driven by the champion throughout that season. The number of possibilities is great, and time is limited. Goodyear will need the model for presentation at the NASCAR Banquet, which takes place each year two weeks after the last race. Many times, the championship is not determined until the last race of the season. So you can understand why both accuracy and speed are required if I am to accommodate my client’s demands.

As a model builder, I take pride in being completely self-taught, while constantly searching for new methods and better techniques to raise my skill level. To a large extent, that’s the fun of my craft. The issue I struggle with most days in my shop is, “When is it good enough?” Whether I’m assessing the quality of an individual part, or a complete model, my answer is this: It’s good enough when, based on my current ability, any further attempt to improve it will probably cause it to be damaged. That having been said, my constant goal is to improve my abilities tomorrow over what they are today. For me, building model cars is a very personal expression. When I cease to improve my skills, and thus my models, I’ll go do something else.

Fifty years later, my father’s words ring more truly than ever, “Patience will produce a much more satisfying result”. Thanks, Dad.

—Michael Dunlap

More views of Mike’s shop show that it doesn’t take a lot of space or expensive equipment to produce world class models.

To learn more about Mike’s work, or to commission high-end custom automotive model art, visit his personal website.

Additionally, you can read a great article from ESPN on Mike’s work building the gold cars for Goodyear. It sheds light on the value of Mike’s meticulously crafted trophies.

View more photos of Michael Dunlap’s craftsmanship.