World-Class Expertise and Technical Innovation in an Age-Old Craft

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2014

About Steve Lindsay

Steve Lindsay was born in Holdrege, Nebraska in 1958. His father, Frank, was an accomplished jeweler, gemologist, and watchmaker. Frank worked with pride on his custom jewelry and precision watches. Steve was often at his side, steadily learning the skills of gold and metal working. Steve’s grandfather was a landscape painter, and his great-grandfather was also an engraver and jeweler. Following suit, Steve began learning the art of engraving at the age of 12. He picked up the skills quickly under the watchful eye of his father.

Steve’s commitment to engraving was solidified when, in 1975, he was offered help from two of his father’s friends, Lynton McKenzie and James Meek (author of The Art of Engraving). It was at that point in his life that Steve decided custom engraving was his future. On the recommendation of James Meek, Steve attended a technical college majoring in tool and die, mold making, and mechanical engineering.

After graduating, Steve worked for a short time in the tool room of a Nebraska manufacturing company. During his off hours, Steve made a lot of the tools that he still uses for engraving today. In 1981, when his tools were finished, Steve began engraving as a full-time career.

During the past 25-plus years, he has engraved for a litany of customers, collectors, and makers. Steve has engraved for worldwide collectors and crafters of custom knives, guns, watches, and jewelry. However, he has also engraved for companies like Oakley Sunglasses, as well as production hand-engraving and lettering for gold, silver, and platinum instrument companies in New England. Later in his career, Steve worked in collaboration with engraver Lynton McKenzie on a Safari Club International rifle. He also continued the engraving work that Lynton had started for watchmaker Gene Clark.

Adding to his repertoire, Steve also created his own folding knives, and engraved gold and diamond knives made by his father. One of the first things that Steve discovered about pocket knives was that many have exposed pins and pivot pins in the bolsters, which can interfere with engraving designs and inlays. Also, because many knives cannot be dismantled, their internal and external surfaces can’t always be fully engraved.

Understanding this, Steve designed several new folding designs and mechanisms. These consist of screw-together folders, with all screws and pins hidden. Reaching inside the bottom edge of the knife accesses the screws. Steve also designed a new locking mechanism, thanks in part to knife maker Barry Trindle. The lock bar is hidden inside, which allows for full engraving of the top edge of the knife.

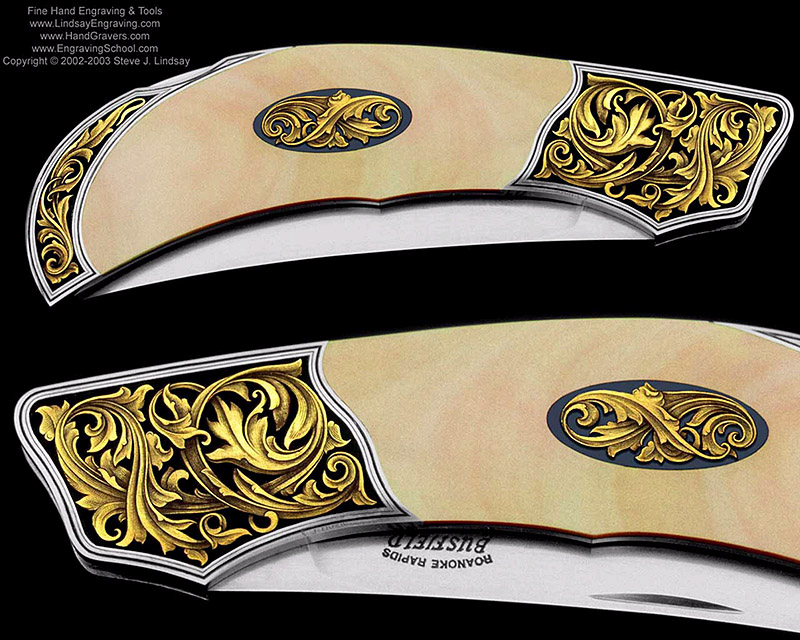

A Jack Busfield folder with apple green jade handle inlays and engraving by Steve. Steve made the engraving on the scroll in banknote style.

Typical of many serious artists, Steve seems to push himself to the max of his abilities. He’s always attempting to find better engraving methods and tools. In the process, Steve has received several patents on the fine control hand-engraving tool that he uses for his work. The time Steve spends developing various tools gives him a break from the rigors of daily engraving. More importantly, Steve’s development of these tools has raised the level of quality and consistency in both his work, and the work of other artists.

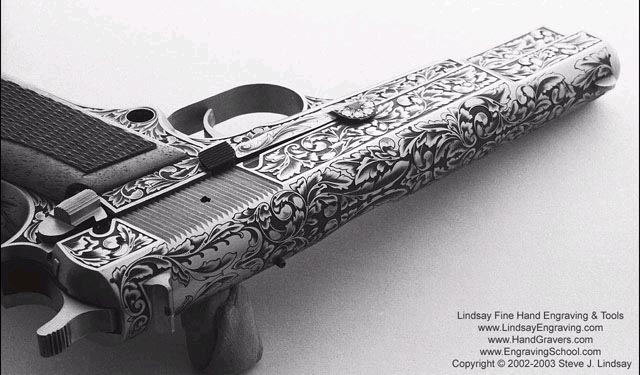

All of Steve’s engravings are hand-cut under a Zeiss microscope. The layout and designs for the engravings are first drawn in pencil. Then, the design is cut under the microscope with a miniature Chasing AirGraver. Steve uses 24K gold for the inlays. Collector value of Steve’s engravings run from $6,000 (for scroll on a medium sized interframe folding knife without gold inlays), to over $100,000 (for elaborately engraved, Lindsay designed and made folding knives).

Making Tools for Engravers

On Steve’s tool website, you can find some of the engraving tools he’s developed for others, along with a full line of tools, vices, materials, books, and videos. His popular PalmControl® AirGraver® regulates the tool’s air flow via palm pressure, rather than a foot pedal. This provides a much more subtle and intuitive approach to engraving. Powered by a noiseless CO2 cylinder with its own regulator, there is no compressor noise, so the tool can be used anywhere.

Artist’s Statement

“The hand engraving artistic vision I strive for is very similar to the feelings created for a listener when hearing classical music. In classical music there is main vein or flow, but many developments are added as the music progresses, making the sound more interesting and beautiful. I work to engrave flowing scroll through space in this manner, including a main flow along with interesting motifs and tangents. I believe everyone searches for beauty. With my engraving I try to suggest beauty for others to discover.”

“I enjoy the mechanical and technical aspects of hand engraving, from building engraving tools to the feel of a graver effortlessly moving in my hand through the metal, creating a clean cut. Producing something that is visually pleasing, and even musical in its finished essence, gives a great deal of satisfaction. Knife making and metal working, for me, is a continuation of the mechanical aspect of creating the work to complete the vision.”

—Steve Lindsay

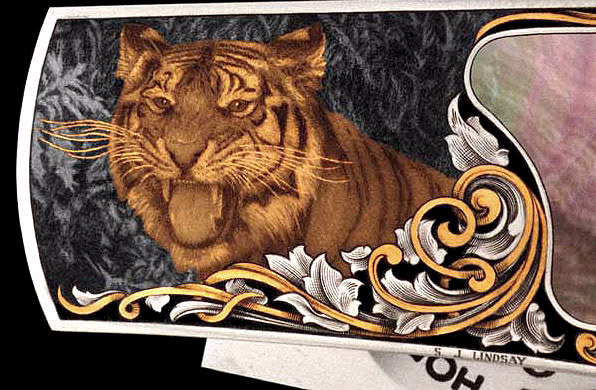

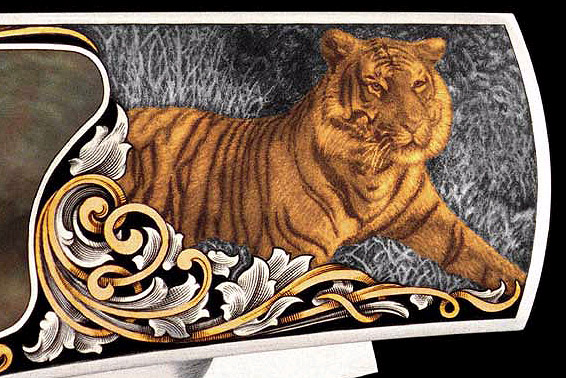

This knife was made by Steve Hoel and engraved by Steve Lindsay. It has black lip pearl handle inlays. The tiger scenes are bulino style engraving.

An Introduction to Hand Engraving

By Steve Lindsay

Hand engraving can be described as the process in which a hardened, shaped and sharpened piece of steel, called a “graver,” is pushed through the metal’s surface. This is done either by hand pressure (push graver), a small lightweight hammer and chisel (graver), or by pneumatic air-driven hammer.

Pneumatic hammers emulate the hammer and chisel and the push graver technique. The graver is ground to a pointed shape adhering to very specific angles. These angles allow the graver to properly enter the metal surface, traveling forward, continuously curling the metal directly in front of the graver face, while leaving behind a small furrow.

The shape of the graver and the angle at which it is held will ultimately decide the furrow shape. The angle can and will often be continuously altered during the process, allowing for the furrow to contain thick and thin graduations of the cut line. If a square shaped graver is used so that one of it’s corners enter the metal, it will produce a V-shaped furrow.

Many graver shapes are available, each leading to a particular style of engraving, and each producing a different result. Usually, the two favored shapes are the “V” and flat. Personal preference plays a significant role in choosing the tool used.

When using the hammer and chisel method, both hands are required—one to hold the graver, and the other to deliver light hammer impacts against the graver, driving it forward through the material being cut. With the push graver method, the graver is generally fitted to a small wooden handle held in the palm.

The graver remains stationary, and the item being engraved is held firmly and fed into the graver’s tip, or rotated into it when a circular or curved line is desired. When making a straight line, the graver is pushed forward using only hand pressure. Each of the these methods requires a rotating vice or a similar holding device, to hold the item being engraved.

The pneumatic graver uses air to drive a small self-contained piston within a graver hand piece. This piston impacts against the engraving tool in the same fashion as in the previously described hammer and chisel method. As with the push graver method, one hand is free to hold and rotate the item being engraved.

In order to create detailed, quality engravings, the engraver is required to accurately execute many cuts or lines which vary in length, width, and depth in the metal. In principal, the results achieved are similar to those produced by an artist when sketching with pen or pencil on paper. Spectacular ornamental engravings are possible when the graver is controlled by someone who is well versed in the art of engraving.

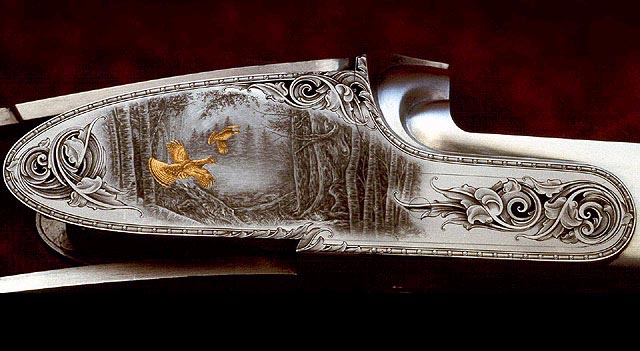

Use of advanced methods, such as “bulino” and “banknote” techniques, allow the artist—if highly skilled—the potential to produce exquisite, lifelike renderings in metal.

Bulino refers to a Pointillism or dot technique. It is derived from the Italian term meaning, “a small, hand held graver.” Today, the term is used loosely to represent the method of creating thousands of small dots or lines in the metal. This enables the control of light and dark contrasts.

Banknote style is a highly organized and systematic method of creating thousands of individual lines, varying in length, in order to form beautifully detailed renderings or ornamental designs. It is generally seen on pages of older texts (e.g. family Bibles), and similar period works of literature printed from engraved plates. The closest and most common representation of this technique in the present may be seen on paper currency.

An artist’s ability to visualize where and how each cut should be placed determines the final outcome of the project. When an engraving artist possesses a talent for visualization as well as a theoretical and technical knowledge, he or she will be able to invest the engraving with richness and character—and even with emotion. Tool geometry and the manner in which the graver is shaped, particularly the face and heel angles, will also determine the quality of an engraving.

The ability to perfectly grind and shape the graver must be mastered; otherwise, clean, accurate, burr-free cutting will not occur, and the results will be unsatisfactory. Badly raised burrs tend to produce visually jagged or distorted lines. This results in a rough, unrefined final product, rather than the smooth, clean results professionals can produce.

If the engraver applies too much downward force while cutting, or the graver heel is too long or too short, burrs will be raised—especially when executing curved lines. A long heel will create drag and a short heel will dig too deeply into the metal. Either way, the metal will be forced upwards, generating a burr along the length of the cut.

Mastering the art of engraving requires expertise in several areas. Those can be divided into two categories: art and craft. Engravers engaging only in craft need not possess drawing and design skills to produce excellent engravings—provided that designs are supplied beforehand by either an artist or by replication of available ornamental patterns.

Many copyright-free (public domain) ornamental designs are available to help the craftsman in this area. The first and foremost ability a craftsman need possess, then, is the ability to precisely control the graver, with an understanding of the technical skills required in order to achieve the desired results.

However, in the case of the engraver as an artist, he or she must have an intense desire to create beautiful original designs, as well as a background in the arts and artistic drawing talent. The art of engraving itself can be a fulfilling medium for an artist to express themselves, and can become a life-long study.

The basic method of hand engraving has not changed for centuries. However, with the advent of modern tools, today’s engravers are given advantages that previous engravers did not have at their disposal. Computer technology allows the use of photo editing or vector-based drawing programs, thus facilitating the design process.

Using computers and printing technologies, an artist can now successfully and accurately lay out a design from the computer onto the item being engraved. Modern pneumatic gravers are available at the size of the gravers of old, allowing ease of control of the graver’s point.

—Steve Lindsay

Keeping Craftsmanship in the Family

The following section details two of the incredible knives that were made by Frank Lindsay—Steve’s father—and engraved by Steve himself. These knives represent the combined effort of two master craftsmen, and the final results are nothing short of immaculate.

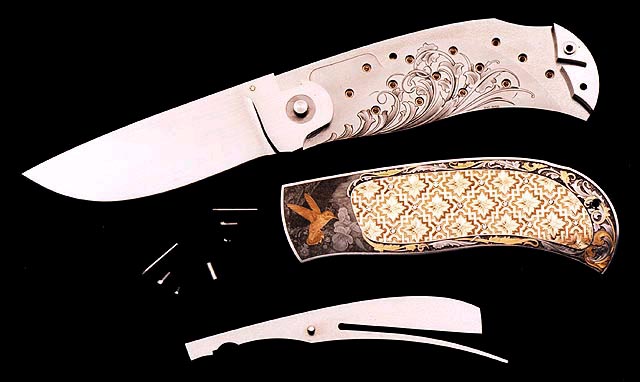

This incredible knife was made by Frank Lindsay and engraved by Steve—making it a fairly unique father-son project. The making of this masterpiece is detailed in full below.

The impeccable knife pictured above was made by Frank Lindsay and engraved by Steve Lindsay. Dubbed the Lindsay-Lindsay #3, this knife was meticulously crafted by Frank W. Lindsay, who is a recognized watchmaker, goldsmith, and gemologist—and also Steve’s father. The numerous jigs and fixtures invented over a period of five years just to make this knife are masterpieces in themselves.

Every surface has been finished with unsurpassed patience. For instance, the finish on the male and female parts of the lock were stoned to a mirror, to keep to almost optical flats for mating. The stones and laps used to achieve this were less than 1/16 of an inch in size, and required many days of hand work under a microscope.

The inside face surfaces of the handle have been finished to the same extent as the outside. The corners and edges are kept much crisper and more square this way. The folder is held together with screws and taper pins. There are no glues or solders used. All the parts are pressed fit. This design made it possible for the inside faces of the handle to be engraved while it was apart.

In fact, a patent was even applied for this design method. The center 18K gold interframe was bright cut engraved. The graver was kept polished to an extreme to accomplish this. Hummingbirds were used for a theme for this piece. The hummingbirds and parts of the flowing scroll are inlaid 24K gold.

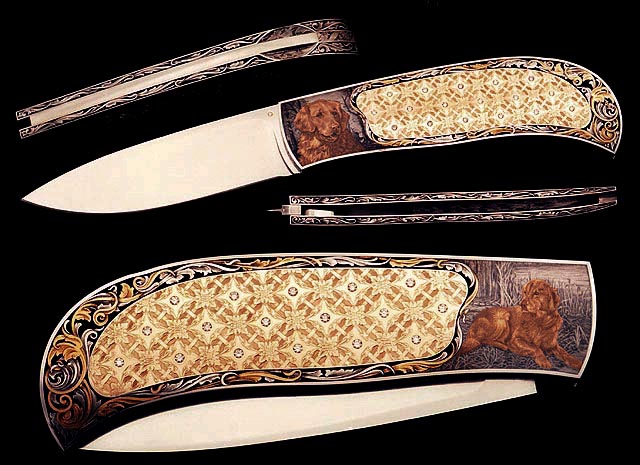

The Lindsay-Lindsay #4 knife, which is detailed in full below.

This is another custom knife made by Frank and engraved by Steve. The Lindsay-Lindsay #4 golden retriever knife took nine months to make and engrave. The knife contains 121 separate parts. There are 34 diamonds in the 18K gold inlay handle, and one in the blade. They are .01 carat full cut stones, and as close to D Flawless and ideal proportions as are obtainable and matched to within .02 mm.

The blade length is 2-3/8” and the overall length is 5-1/2”. The blade and locking bar are made from ATS 34 stainless. The blade has a hardness of 59 Rockwell on the C scale, and was triple tempered with one being sub 0 of -100F to impart toughness.

The frame and other parts are made of heat-treated 416 stainless. The diamond settings are made of 18K wire. The folder is held together with screws and taper pins. This design made it possible for the knife to be engraved while apart. The inside face surfaces of the handle have been finished to the same extent as the outside, and have also been engraved.

The center 18K gold interframe was bright cut engraved. The graver was kept polished to an extreme to accomplish this. The golden retrievers and parts of the flowing scroll design are inlaid 24K gold.

The Lindsay-Lindsay #4 knife is shown disassembled here to reveal its parts. The second inlaid golden retriever is also pictured.

Other Interests

One look at Steve Lindsay’s website will reveal that he doesn’t restrict his creativity solely to engraving and drawing. At the time of this writing, Steve was also working on several auto restoration projects, including his wife’s MGB and his own 1969 Corvette 427. Steve is also interested in computers, and has posted some software on his site for a digital readout program, and a program for designing arrows.

More About Steve Lindsay’s Work

For more examples of Steve’s work, including pieces for sale, see his personal website.

To read some magazine articles featuring Steve’s work, and explaining his philosophy and techniques, visit the following links:

Additionally, you can view more photos of Steve Lindsay’s award-winning craftsmanship.