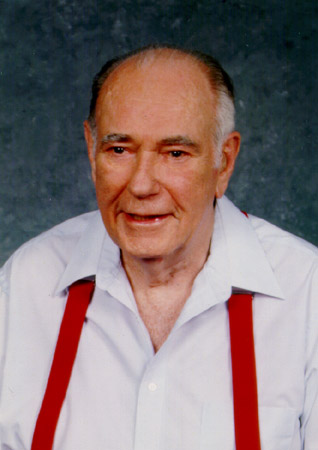

1921—May 10, 2016

A Master Watch and Clock Maker Devoted to Educating Others

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2000

Mr. William R. Smith of Powell, Tennessee was selected by the Joe Martin Foundation as the Craftsman of the Year for 2000. Mr. Smith was chosen for his outstanding craftsmanship, and lifelong contributions to the field of horology.

Introduction

After being selected by the Joe Martin Foundation as Craftsman of the Year for 2000, Mr. William R. Smith provided an autobiography for our records. Readers will quickly realize that Mr. Smith was a man of many talents. Regardless of the field, when he became involved with a subject, Smith pursued it until he had mastered every aspect. His experiences varied from clock building to helping construct the world’s first sector focusing cyclotron at Oak Ridge, TN.

During World War II, Mr. Smith received the Legion of Merit award for his work with aircraft instrumentation. William always worked to understand every part of a given project, and frequently took the time to learn new processes. In doing so, he rarely had to turn work over to others, as he had mastered the skills himself. William was involved in watch repair, instrument repair, ham and CB radio, photography, videography, and printing. He also wrote many articles and several books. Mr. Smith’s talent for photography and writing allowed him to share many of his clockmaking skills with others.

Along with his degree in mechanical engineering, Mr. Smith held the following credentials: Fellow in the British Horological Institute (FBHI); Star Fellow in the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors (FNAWCC); Certified Master Clockmaker (CMC); AWCI Certified Master Watchmaker (CMW); and Certified Master Electronic Watchmaker (CMEW). Additionally, he also won the Dana J. Blackwell Clock Award from the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, which recognizes an individual for excellence in the field of clock making.

We regret to inform that Mr. William R. Smith passed away May 10, 2016. His legacy as a master clock and watch maker is preserved through his outstanding work, and through his many books—which can still be found and purchased on the W.R. Smith website.

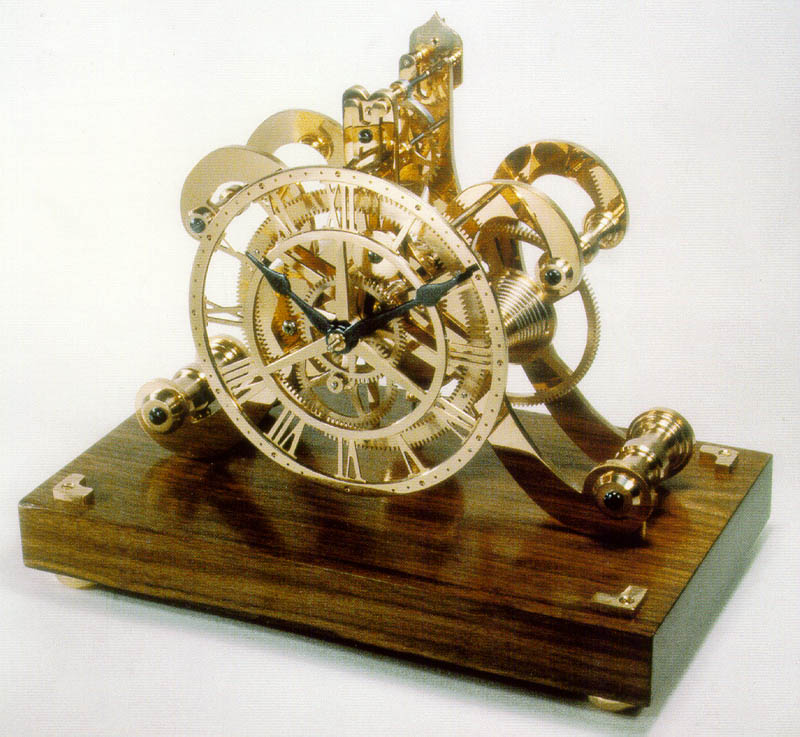

This scroll skeleton wall clock stands 9” above its black walnut base. The clock is one of Mr. Smith’s own designs, and won a silver medal in international competition at the NAWCC Craft Contest for handmade clocks. It has a seconds beating pendulum, weight drive, and an 8-day run. All of the parts were made in Mr. Smith’s shop, except the 47-strand stainless steel cable and the commercial Roman numerals in the dial.

Autobiography

By W.R. Smith

I was born in Atoka, Tennessee in 1921. This is a country town that is typical of those formed around depots that the new railways placed every so many miles along their tracks. My mother was a homemaker and my father was a farmer who specialized in the raising of sweet potatoes—about 5,000 bushels per year. Thus, at an early age I learned to use all sorts of horse and mule-drawn farm equipment for tilling the soil and raising crops.

At a very early age, I showed considerable mechanical talent and was always interested in all types of machinery. By the age of ten, I was wiring houses as a part of Roosevelt’s REA (Rural Electrification Program). I also became involved in ham radio, the repair of automobile engines, etc.

One day, at age fourteen, a local merchant opened his cash drawer and handed me a pocket watch, saying, “Here Bill, you fix everything else, see if you can make this watch run again.” Using my mother’s eyebrow tweezers and a screwdriver made from a nail, I managed to remove the watch from its case and remove the balance cock. The hairspring had thrown a coil over an upper portion of itself, and this was easy to set right. This convinced me that I should be a watchmaker. I then went to my grandfather to plead for the money in my $15.00 bank account so I could purchase tools. After hitchhiking twenty-nine miles to Memphis, Tennessee from my home, I purchased less than a handful of tools and set about learning the watch repair trade.

This lyre skeleton clock stands 16” above the base. Another one of Mr. Smith’s original designs, this clock contains a never before used spring pallet escapement that William created. It won a gold medal in international competition at the NAWCC Craft Contest for handmade clocks. All parts were made in Smith’s shop, aside from the mainspring and 47-strand stainless steel cable. The dial was sawn from 3/32” brass sheet with a handheld piercing saw, and the numerals were filed to shape.

These were the days of the Depression, and there was no hope of any kind of formal schooling. As a solution, I began a four-year trek to Memphis each Saturday, rain or shine. From the middle of town, I visited every watchmaker in walking distance that would allow me in his shop. To a man, they would allow me to look over their shoulders as they worked, or, if I had a problem, they would stop their work, listen, and offer a solution.

At times, they would actually demonstrate what needed to be done. They also allowed me to sit in their shops and read their watchmaking books and magazines. Thus, I repaired watches during my high school years, and faithfully made the Saturday trips to the Memphis watchmakers.

By the time of my graduation in 1939, I and my capabilities were well known in the area. I was recommended for a job in a ten-man shop that did trade work for Sears. This exposed me to the skills of many people, and was far better than any training I could have obtained in a formal school from one or two teachers.

While working in this shop, the war clouds were gathering, and the government began offering free courses in many crafts. Several of us from the shop enrolled in an aircraft instrument training course. It was from this course that I, at age twenty, and eight others volunteered for the Air Corps.

After basic training in Mobile, AL, I was sent to an instrument school in Chicago, and later to one at a Bendix instrument factory. Finally, we were absorbed into the then-forming 27 Air Depot Group of the 5th Air Service Command, and were sent to Australia. There we gathered the needed materials and headed for Port Moresby, New Guinea.

A crew was sent into the jungle to set up a sawmill, and with the lumber we set about building an air depot for the complete overhaul of aircraft. Because of my training, I was a member of the aircraft instrument shop, which did mechanical, electrical, and gyro instrument repair. I worked in the shop during the day and repaired watches at night.

This grasshopper skeleton clock, designed and built by William, stands 17″ above its base. It features a grasshopper escapement with a never before used double escape wheel. The clock has a compound pendulum that swings 72 beats per minute. The dial was hand sawn from solid brass sheet with a piercing saw. All parts were made in Mr. Smith’s shop, except for the mainspring and cable. Without the compound pendulum to slow the beats per minute, a 27″-long pendulum would have been required, and the clock would not have worked on a tabletop.

Test equipment for such a shop was almost nonexistent. To solve this problem, I designed and built (or had built) some forty-plus pieces of test equipment. This allowed instruments to be tested and repaired, which put grounded fighter planes and others back into the air again. For this work, General Douglas MacArthur awarded me the Legion of Merit, the military’s highest non-combat medal. With it came five extra service points that allowed me to return home sooner than all others in the depot.

After two years in the instrument shop in Port Moresby, our depot was moved north to Finschhafen, New Guinea to be nearer the front. We were absorbed into a depot that was already there. I was assigned to take care of the instruments in a group of C-47’s that unneeded test pilots were using to fly cargo. Because of my ham radio background, I signed on as a radio operator in the group and flew for my remaining year in New Guinea. By then, the war had ended and I returned home and married.

Taking advantage of the GI Bill of Rights, I enrolled in the mechanical engineering college of the University of Tennessee. We were assigned a small trailer in a 125-trailer park created by the university for returning veterans. The rent was $15.00 per month, which also covered electricity and water. I continued to repair watches during my four years at the university. In our small trailer, we had a 600-Watt ham station, a watchmaker’s bench, a spinet piano and a homemade folding table.

Following graduation, I took a job as a mechanical engineer at the Y-12 plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. About twelve years were spent at this plant. By that time, we had received funds to build the world’s first sector focusing (strong focusing) cyclotron at the X-10 site. I was Chief Engineer for the project for a total of about fifteen years.

During the early part of this period, I continued to repair watches and clocks, but finally became involved in other things. I also had to travel a lot for the corporation. During this period, I had a number of engineers and designers working for me, and was responsible for all of the work being done in local and other shops to create the cyclotron. This required travel to many vendors’ shops.

After the machine was built and operational, I transferred to the K-25 plant to help in their plant expansion effort. However, the government had demanded that a safety analysis be done for the plant, and their first effort had been rejected. I was then called in and told, “We can hire PhD’s in English by the dozens, but they can’t write engineering. We can hire engineers by the dozens, but they can’t write English. You can do both and we need you.” For the remainder of my ten-year stay at K-25, I served as a technical writer and editor for the Safety Analysis Program.

In the early sixties, citizen band radio was a big thing, and there was a demand for someone in the Knoxville area to repair CB radios. Because of my lifetime involvement in ham radio (I still hold license W4PAL), and the fact that I had the FCC required broadcast license, I set up shop in my 1500 square-foot basement. From there I did CB sales, service and manufacturing in the evenings for a period of over twenty years.

My main product was the “Windjammer,” one of the first power microphones offered for use by CB’s. These were done in lots of 1,000 each, and involved the use of a 14-ton punch press, nine sets of dies, silk screens, and a crew of fourteen people during an assembly run.

This skeleton clock stands 8-1/2” above its base. Mr. Smith built it in 1980, based on a photograph of an 1830’s William Strutt clock that he found in a book. It was awarded a gold medal in international competition at the 1982 NAWCC Craft Contest for handmade clocks. This clock is unusual in that it has an epicyclic train and no motion works. The dial was hand sawn from 3/32” sheet brass with a piercing saw, and the numerals were filed to shape. All parts were made in Mr. Smith’s shop except the mainspring and 47-strand steel cable.

After thirty-five years at the plants, I retired in 1984 at age sixty-four. At about that same time, the safety analysis we had been working on for many years was accepted. About seven years before retirement, I began designing clocks and workshop tooling, building them, and writing in the field of horology and modelmaking.

To date, I have published about 64 articles in these fields, have published six workshop manuals, and have produced four workshop videos. The videos are now available in both VHS tape and DVD format. Since the start of these efforts, in international competition I have been awarded four gold medals for hand-made clocks, one silver medal and one bronze. I have also received a gold metal for a tool design.

I recently completed work on my sixth book, How to Make a Strutt Epicyclic Clock. This clock is highly unusual in that it has an epicyclic train. The book is a 128 page, 378 figure workshop manual for building the clock.

Although I have never worked in a machine shop, my early years of turning, tempering and working with metals in the repair of watches and clocks has made it easy for me to master new and different techniques required for other tasks. Also, as Chief Engineer of the cyclotron project, I traveled to shops across the nation. This allowed me to meet and study the work of some of the world’s finest craftsmen.

This is the second Strutt epicyclic clock that William built in 2003, and documented in one of his last books. He had already built his first Strutt clock in 1980, but didn’t chronicle the construction process. After many requests, Mr. Smith completed another version of the clock, and this time he fully recorded its production in a book. With its unique Ferguson Paradox motion work, and epicyclic (planetary) gearing, it is truly one of the most interesting skeleton clocks you can build.

Following my retirement, I purchased a home in Powell, Tennessee. In it I have a three-room basement workshop that includes a 12′ x 12′ machine shop, a 12′ x 12′ darkroom, and a 12′ x 24′ main shop.

To publish a clockmaking workshop manual, I design the clock, photographically document each step of the construction, process the film in the darkroom, write the text, set type on the computer, and have it print out master pages that are camera-ready except for waxing in the halftones. These are then made in the darkroom, added to the pages, which are then photographed to 8-1/2″ x 11″ negatives using my own 14″ x 18″ process camera. The negatives are then masked and used to burn offset press plates in a homemade contact print frame.

The plates are installed on my offset press and the pages printed. These are then collated, punched and bound—all in-house. My workshop videos are also produced in-house.

I sell my books, videos and DVD’s from Powell, and my workshop manuals and videos are also sold across Europe by RiteTime Publishing in England. It is in this manner that I am hopeful of honoring the memory of many kind souls who invested their time in a poor farm boy who had no money, but a burning desire to learn. I am always delighted to try to be of help to modelers with my books, videos, or personal experience.

—William R. Smith

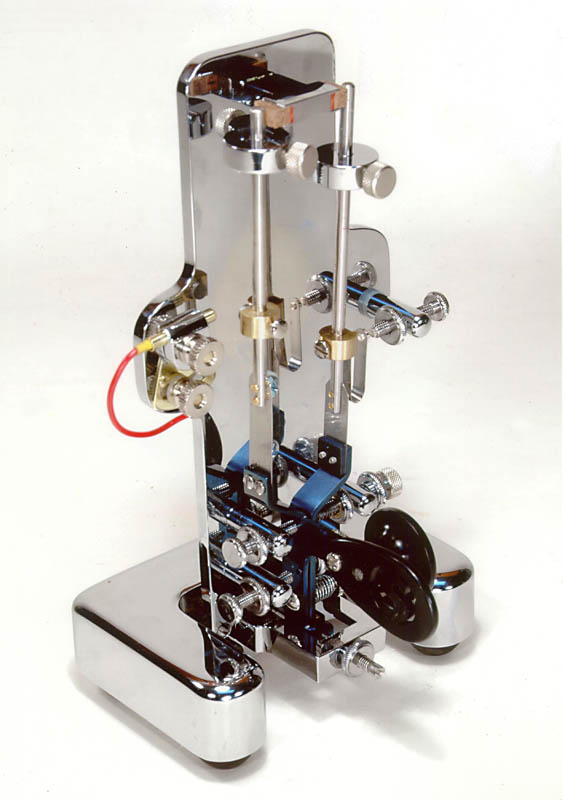

As of 2005, Mr. Smith had been involved in ham radio operation for 73 years, having built his first telegraph speed key at ten years old. Busy working on his clocks, he had been off the air for 16 years. However, William decided to get back into the hobby with three stations operating from his home. Once back on the radio, Bill became interested in telegraph keys again, and decided to make one that was both unusual and special. Ultimately, he built this Duovert, which is the world’s first and only vertical, mechanical, fully automatic (both dots and dashes) telegraph speed key.

The Duovert stands 8” tall, weighs 4-1/4 lbs., and has a speed range of 13-35 words per minute. The base, main frame (bridge), and hardware were made from chrome-plated brass. The foot was made from 1”-thick, chrome-plated brass with rubber feet. The dash and dot levers are heat-blued steel. The signet paddle was hand sawn from a sheet of black plastic. While making it, Bill found himself learning new and interesting skills, like plating and hand fabrication.

While Mr. Smith has passed, his instructional videos, books, and photos of his work can still be found on his website—along with his full autobiography.

View more photos of William R. Smith’s unique telegraph speed keys.

This section is sponsored by:

Makers of precision miniature machine tools and accessories. Sherline tools are made in the USA.

Sherline is proud to confirm that William R. Smith used Sherline tools and components for some of his small projects.