Historically Correct Perfection in Miniature

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2015

“For me, the process starts with the study and research of the original object. It is important to understand the ways, tools and methods used by the original craftsman… When I reduce an object to a smaller scale I must be careful to maintain proper proportions, while at the same time adding an artistic interpretation… Even after 30 years I enjoy working in my studio, which can at times be either peaceful or very challenging, as I strive to make each new piece better in some way than anything I have done before.”

—William R. Robertson

William Robertson’s World in 1/12 Scale

In the realm of miniature model making, William Robertson’s work is some of the most highly sought after in the world. To those who build and collect dollhouses and tiny scale furniture, among other objects, the term miniature typically means 1/12 scale (1”:1’). Much of Bill’s work in miniature is done at this scale, and he’s made a living working full time on his projects since 1977.

At auction, some of Bill’s pieces command prices up to five figures. He works with both wood and metal, and creates individual pieces as well as complete rooms. Bill’s work has been displayed by institutions like the Smithsonian and the National Geographic Society. A large body of his work can be seen at the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures in Bill’s hometown of Kansas City, Missouri. In fact, he even helped design the display!

It may come as no surprise that Bill has been consulted on the proper display of miniatures by a number of museums. He contributed significantly to the design of the Kentucky Gateway Museum Center in Maysville, Kentucky, along with some now closed museums in Dallas, Texas and Naples, Florida. Mr. Robertson has traveled the world to share his knowledge with peers in schools and seminars across the US, Europe, and Asia.

Prior to constructing his miniatures, Bill does a tremendous amount of research on his subjects. He always aims to make every detail historically correct. Bill’s miniatures must be replicated to perfection down to the tiniest details—like a tiny working lock and key on a tool chest.

Getting an Early Start

As a young boy growing up in Washington, D.C., Bill’s parents would often drop him off at the Smithsonian Museum, where he would spend entire days. His interest was not just with models themselves, but also in how they were displayed. At the age of 15, Bill was working in a hardware store and building models of his own. He worked on everything from race cars to electronics.

At one point, a neighbor asked Bill if he could repair some wooden puzzles for $100.00. He thought this was a very generous offer until the neighbor arrived in her Oldsmobile station wagon. The trunk was filled with puzzles!

After a week of hard work with a jeweler’s saw, Bill had certainly earned his money. The experience may not have increased his appreciation for puzzles, but it did help spark a lifelong passion for doing precision work. Not to mention, the jeweler’s saw is still one of Bill’s favorite tools. He spends hours hand sawing the tiny dovetails and intricate details of his miniature cabinetry, and still finds the process very relaxing.

A Workshop Dominated by Hand Tools

Building at 1/12 scale means that the advantages of power tools are minimized, and the work often calls for the precision of hand tools. Power tools are good at removing large amounts of material at a rapid pace; however, the delicate control afforded by fine hand tools—or smaller precision power tools—is usually required for extremely small and detailed parts.

Bill makes small metal parts on a lathe, and grinds his own tiny router bits in order to make up scale moldings. While working with one of his small hand planes, he noted that, “A scale plane takes a scale shaving.” Bill has a Rose Engine ornamental turning lathe, and is a big fan of Rivett lathes as well as many other fine tools. But like his work, most of Bill’s tools are small.

The one full-size tool project that he took on was reproducing a large, historically accurate drill press for display in a replica of Wilbur Wright’s workshop. That was a particularly massive piece, especially when compared to Bill’s usual scale. The drill press turned out well, but when describing the project afterward, Bill remarked, “What was I thinking?”

Obviously, smaller is better in Mr. Robertson’s workshop. What all of his tools have in common, though, is quality. While good tools won’t turn a hack into a master, even craftsmen with the utmost ability cannot reach their ultimate potential when hampered by poor or dull tools.

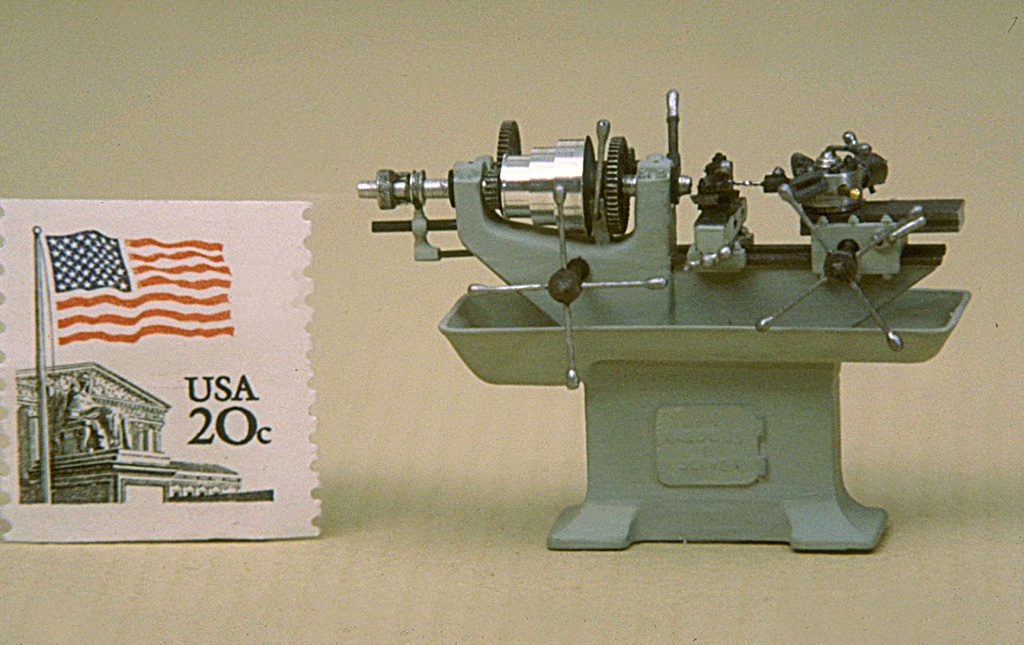

Two of Bill’s 1/8 scale machinist’s chests, circa 1880, with working miniature tools. The postage stamps lend a sense of scale.

The Creative Process

In terms of his approach, Bill noted, “For me, the process starts with the study and research of the original object. It is important to understand the ways, tools and methods used by the original craftsman.” He went on from there to describe the challenge of selecting the correct materials, which involves replicating the grain and color of the original. The next step is to reduce the parts to scale size—a process that involves both mechanics, and artistic interpretation.

Some of the smaller parts can be extremely challenging to make simply because of the physics involved. Keep in mind that 1/12 scale means a cubic volume reduction that is 1/12th width X 1/12th length X 1/12th height—or 1/1728th of the original size of a part.

Miniature Tool Chest Featured in Fine Woodworking Magazine

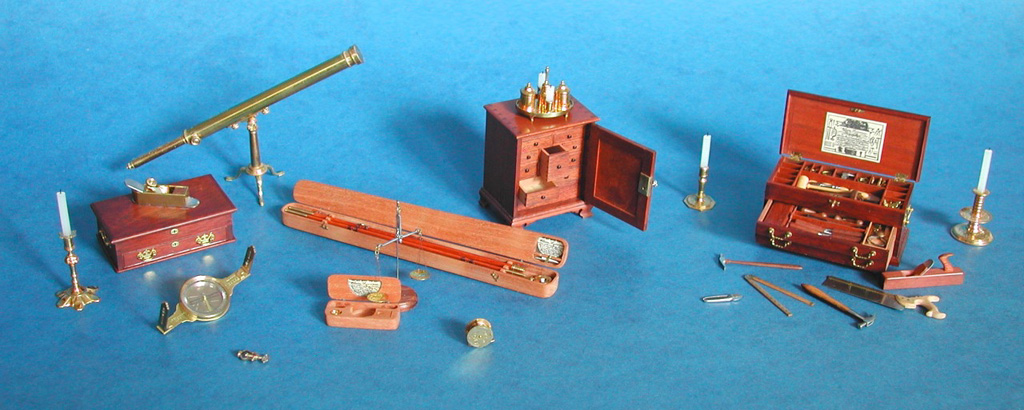

Some years ago, Bill completed a miniature 18th century Hewitt gentleman’s tool chest. The chest was featured, among other places, in Fine Woodworking magazine in 2012. The chest is complete with all of the planes, chisels, and saws that a craftsman of the era would have used. They are all reproduced in miniature, down to the finest detail. Even the key lock on the chest is functional! This is the piece that first brought Mr. Robertson’s work to the attention of the Joe Martin Foundation.

Notably, the chest showcases both Bill’s wood and metal working skills. Over 1,000 hours were invested in the construction of the tools and toolbox. It illustrates the lengths to which Bill will go to get every detail just right. That includes the 5-leave hinge on a tiny folding rule, or the label on the underside of the lid, which is printed (in perfect scale) on actual 18th century paper!

Passing on His Skills to Others

Now, Bill Robertson is a teacher as well as a craftsman. He shares his skills and techniques in schools and seminars around the world. Bill is a regular at the International Guild of Miniature Artisans school in Castine, ME, along with the Miniature in Tune summer school in Denmark. Bill posts regularly on the Practical Machinist website forum for “Antique Machinery & History.” In those discussion forums, Bill shares his work and some of the antique tools from his collection.

Interestingly, Bill posts under the username of “rivett608” in honor of his favorite lathe. He also travels to Europe and Asia to pass on his skills to those interested in making fine miniatures. Bill noted, “For me, the best part of making miniatures has been the wonderful opportunity to meet, and share work and techniques, with collectors, artists, and historians from all over the world.”

A Closing Word About Fine Miniatures

Often called “Dollhouse Miniatures,” this term is a little misleading. The 1/12 scale work created by this highly-skilled group of craftsmen, of which William Robertson is certainly among the most respected, is not intended for the kind of toy dollhouses a child would play with. At the top end of the collector market, these are miniature worlds reproduced to the highest level of perfection possible—and with great historical accuracy.

Often displayed in the setting of a miniature room, or dioramas with one wall removed (much like a dollhouse), these pieces are collected worldwide by those who appreciate the kind of fine craftsmanship demanded by precision work in miniature. Quality and price can vary tremendously depending on the skill and reputation of the builder.

A beginning collector can start with a simple room kit, and purchase a few inexpensive, mass-produced pieces of furniture for decoration. By contrast, at the top end of the scale, collectors will spend many thousands of dollars to create perfect miniature worlds of museum quality. The latter, top end collections are where Bill Robertson’s pieces reside, and his quest for perfection continues.

Bill noted, “Even after 30 years I enjoy working in my studio, which can at times be either peaceful or very challenging, as I strive to make each new piece better in some way than anything I have done before.”

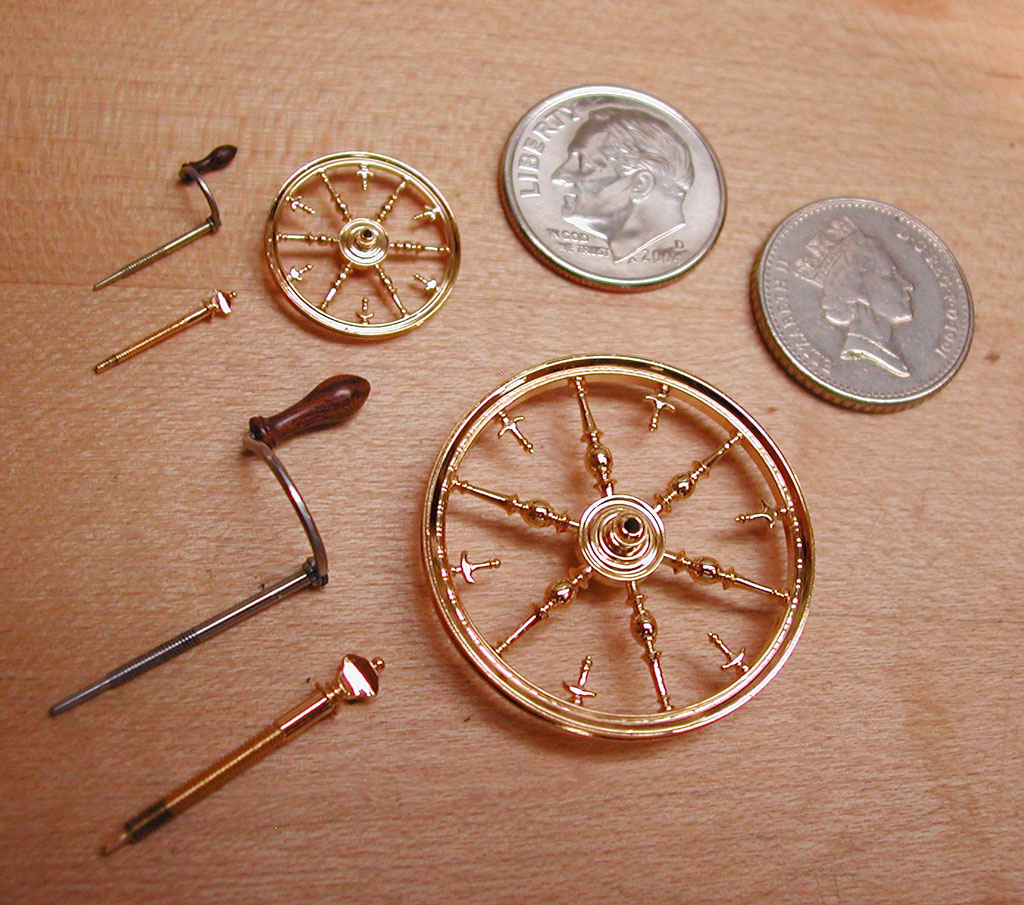

Shown here are two 18th century French table top silk spinning wheels—made at 1/12 and 1/6 scale, respectively . For this project, Bill actually bought the original to use as a model for his miniatures, which can be seen in the background. Bill also wrote about the construction of these miniatures.

Investing in Art

One of the goals of the Joe Martin Foundation is to see that fine craftsmanship is recognized, and properly appreciated and rewarded. One gauge of that appreciation is the price people are willing to pay for a craftsman’s work. For reference, a 1-1/4” wide walnut-cased drafting set made by Bill recently sold for $18,750 at a Leslie Hindman auction in Chicago, featuring a large collection of miniatures.

In addition to that, a 1” rodent trap built by Mr. Robertson in 1985 sold for $13,750. In similar fashion, a 2-3/8” tall maple and wire bird cage with a peaked top and swinging canary also sold for $13,750. Like other fine art, miniature pieces made at this level of master craftsmanship continue to increase in value, making them a good investment for the collector.

Bill (left) and his parents are shown here at the Kentucky Gateway Museum Center, Maysville, KY. This photo was taken at the opening of the “Wm. R. Robertson Fine Arts Rotunda,” in 2008, which Bill designed for the Kathleen Savage Brown Collection. He designed the round gallery as a showcase for fine miniatures. It has inlaid marble floor, Venetian plaster walls, and a domed ceiling with an oculus (like the Pantheon) under a fiber optic starry night sky. Bill thanks his parents for all of their support and encouragement over the years.

Bill’s Latest Project—A 1/12 Scale English Architect’s Table Circa 1770

One of Bill’s latest miniatures is a 1/12 scale model of a unique type of table from 1770. The table would have typically been found in a gentleman’s library, and was used for drawing or displaying manuscripts or books. The utilitarian table was made in a simple Chippendale style, which was popular during the Georgian period. The miniature features squared straight legs with internal Tucson columns ending in brass castors. The internal edges have a delicate molding on the inside of the legs and aprons.

Additionally, the functional lock can be opened with a tiny key. Once unlocked, the front of the table—including the front legs—opens up to reveal a leather covered writing surface. The writing surface has two half-moon handholds to help push it back into the body of the table. When pushed in, a drawer fitted with compartments is revealed.

The compartments were dadoed together, and have cupid’s bow detailing on the top edges. The miniature trade label in the back compartment was printed on 18th century paper. True to the period, the label contains a scratched deletion.

On the right side of the table is a small hidden dovetailed drawer, often used to hold ink. A pair of candle trays pull out from each side with cyma curves, allowing the light emitted from the candles to shine as far forward as possible. This provides illumination of the working surface without shadows. (This feature, among others, was discovered while Bill was sitting in his candlelit study, examining two of the full-scale tables.)

When a spring-loaded button latch on the opposite side of the table is pushed, the table top can be tilted upward. There is a hinged rest that fits in a series of carved notches to hold the top in position. One of the most fascinating features of this table is the book rest. When the table top is in the down position, the rest is retracted, leaving a flat surface for drawing. However, when the table top is tilted upward, the rest rises up to support books or papers from falling off the slanted surface. The scale miniature architect’s table is made of Swiss pear wood.

The desk is fully jointed with mortices and tendons, dowels, dovetails, dados, and other joints. The moldings were cut with specially made cutters. The hardware, including the lock, latch, castors, and spring mechanism, were all machined out of brass and steel. These pieces all function like the originals. The tables were stained, and have a carefully hand-rubbed lacquer finish. There is an engraved nameplate on the bottom of the piece, which is also signed on the hinges and label.

Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2015

Each year the Joe Martin Foundation selects one individual as the outstanding craftsman of the year. An award of $2,000.00, plus a plaque and engraved medallion, are presented to the winner. Normally, the presentation is made at the North American Model Engineering Society Expo in the Detroit area in April. However, Bill had already commited to another show on that date. Fortunately, Mr. Robertson was able to travel to California to accept his award at the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum in Carlsbad on February 28th.

While at the museum, Bill spent the day talking with visitors, explaining his techniques, and demonstrating the art of cutting tiny dovetails for wooden drawers. Bill is the 19th winner of the award. Pictures from his visit to the Craftsmanship Museum can be seen here, and in the link at the bottom of this page.

Bill brought this 18th century machinist’s tool box to show museum visitors. He kindly donated this piece, and two other miniatures for display in our collection.

Bill Robertson Ted Talk

Bill Robertson’s remarkable body of work even includes a TED talk, where he shares the story behind his historically accurate miniatures, which have been featured in museums around the world.

Additionally, in another presentation Bill shares details about his painstaking approach to work, and what goes into his astonishing miniature creations. To learn more about these miniature masterpieces, visit Mr. Robertson’s website.

View more photos of Bill Robertson’s extensive collection of award-winning miniatures.