By Bill Gould

In looking back over my forty plus year career as a professional designer and model maker, I realize what a blessing it is to do that which you truly love. The neat thing is that you never know what your next project will be, and each will teach you something important. And, you never get bored!

I often wonder what draws us to this unusual profession, and what leads to success on this chosen path. It can be quite a challenge at times, especially when dealing with demanding clients and deadlines. You see, it is one thing to make something for personal enjoyment and satisfaction, yet quite another when your livelihood depends on it.

Most of us like to “make” things with our hands. It’s human nature—after all, we are bipedal. We all have a unique contribution to make to society, and each of us is uniquely blessed with abilities that, given the proper guidance and direction, have moved mankind from the caves to our present, often contradictory, society.

But I want to talk about the “Craftsman” in the classical meaning of the word. Those who make things by hand, in a manner that exhibits mastery of their craft, whether as an avocation or profession.

What is a Craftsman? Of course, I use this with non-gender intent, for throughout history men and women alike have excelled as craftspersons, and even more so today. I often ask; how do we, in today’s high-tech world, truly define craftsmanship, and identify those who are or may become one? And, most importantly, why should we care?

“The Craftsman, in (the) old-fashioned sense, seems now to be so rare as to lead many to speak of his extinction”… Eichner was; to a degree which could be instructive to others in this century who are blessed with the ability to ‘make things’ of such obvious superior quality as to overcome the advantages of the machine”. (Italics mine.)

These words are quoted from a brochure describing Laurits Christian Eichner (1894-1967) for a 1971 retrospective exhibition of his life’s work at the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC, with text by Robert P. Multhauf. It was given to me around 1972 by Robert Vogel, a curator at the Smithsonian, and it had a huge impact on my life and career.

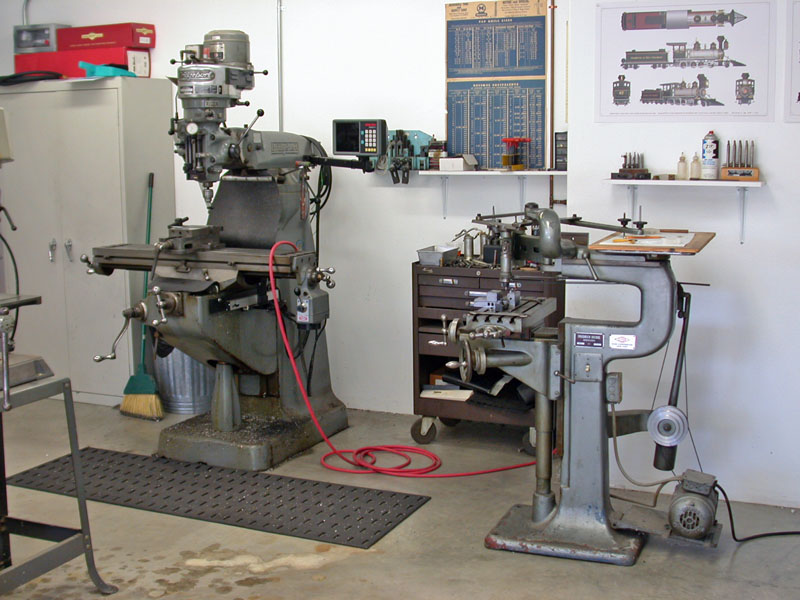

This view of Bill’s shop shows his Bridgeport knee mill, and Deckel G1-L 2D engraving pantograph. On the wall is one of his full color lithograph prints.

Mr. Eichner, whom I unfortunately never met, was a consummate craftsman, whose work ranged from hand-wrought pewter and handcrafted clocks, to armillary spheres, museum models, replications and restorations (most for the Smithsonian), and the invention and construction of many important scientific instruments for space exploration and physics. Simply put, he was a genius and a Master Craftsman by any definition, and is one of my “heroes”. Look him up on the internet.

I think the most important attribute to becoming a Craftsman is the desire to make things exceptionally well. This desire is likely the result of our personality and upbringing; in fact, it may even define our personality—the desire to succeed, to constantly learn, to strive for perfection, and, above all, to “stick with it.” All children, almost from infancy, exhibit traits that, if nurtured, often translate into their life’s work. I can’t emphasize enough that these early indicators must be honored and supported. These early traits may lie dormant for many years as we pursue varied careers, coming to the forefront only later in life in the form of a hobby, avocation or second profession.

The second most important factor is an insatiable curiosity about the world around us, and what makes it work. The marvel and mystery of tools, machinery, processes, materials and how to put them together is at the core of almost all invention and discovery. Behind all engineering endeavor are the men and women whose skill, expertise and passion made it possible. From Da Vinci and Galileo to Fraunhofer and Edison, all had curiosity in common, and a willingness to learn everything possible in their field—in short, to master their craft.

Craftsmanship is the training of the eyes, hands and mind to accomplish a given task with ease and seemingly effortless application of energy, to bring forth objects of great beauty with minimal energy expended.

Bill’s favorite lathe—a 1907 belt-driven Potter 7” x 18” Instrument Lathe. With cone bearings, it was still capable of .0005 tolerances. It’s fully tooled, including double tool cross-slide, turret tailstock, full collet set, and the usual chucks. Note that Bill fits all of his machines with either dial indicators or digital readouts.

When I was employed as a model maker at Hughes Aircraft in the late 1960’s, my “bench mate” was a craftsman of exceptional skill. Ellis Slankard, then in his early 60’s (I was 23), had apprenticed as a patternmaker at age 12, worked on the “Spruce Goose,” carved patterns for the DC-3, and hand carved the Presidential Seal for President Roosevelt. We would joke that “Ellis works slower than grass grows.” However, every project he worked on came in under-budget and well ahead of deadline. He was so well trained, with so much experience, that he simply never wasted a motion. He would pick up a tool, say a chisel, make a few precise strokes, put it down, and pick up the next tool. No wasted effort, and seemingly without thought, yet it was obvious to me that he had planned his work hours in advance. He was a very calming influence on a young, rather energetic, budding craftsman. Ellis is another of my “heroes”.

The third important attribute of a craftsman is perseverance. The path to becoming a craftsman is arduous; it can take many years to achieve the goal, just as a musician can only reach the concert hall after many long years of practice. To achieve mastery is difficult work; you must be willing to never accept second-best, even if it means completely reworking a part, or starting over, on your “own time,” of course. There are few shortcuts in life; we learn through our mistakes. However, as my favorite aunt would say, “Be aware of accidents, for they may be genius in disguise.”

A violinist may say, “I play a Stradivarius.” We know that he or she really means “I play a violin,” but in fact is honoring and acknowledging the Master Craftsman who made that violin.

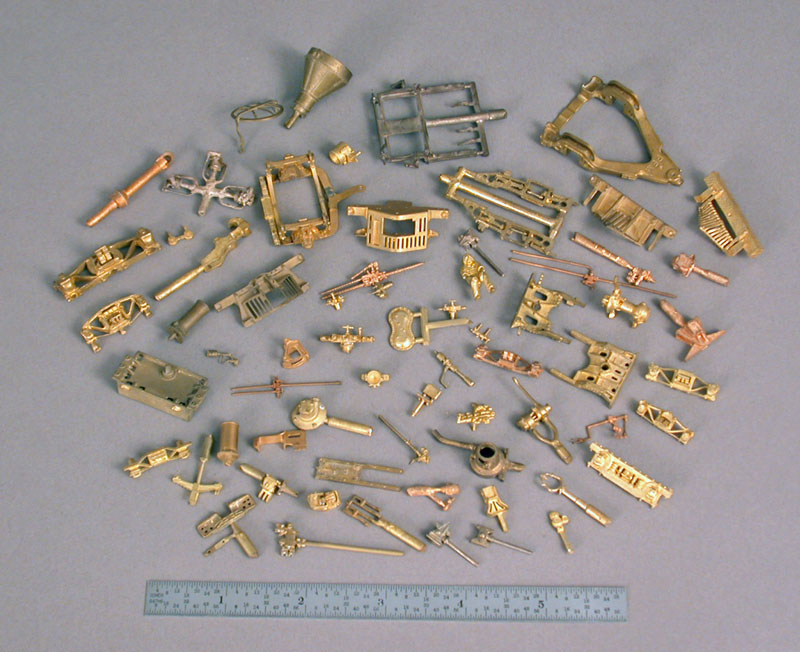

An HO scale kit of the Santa Fe coaling tower in Lamy, New Mexico. Bill designed and tooled this plastic kit for the Tichy Train Group.

Why Should We Care?

I honestly believe that our attitude about craftsmanship is a bellwether of our society.

My work, especially with museums, has often required me to study the techniques and application of early technology to our industrial and scientific past. One thing became quite clear; in the past exceptional craftsmanship was the norm, and this expectation largely reflected the society of its time. Mastery of your trade or craft through apprenticeship, discipline, perseverance and respect for your elders were expected of all, and most importantly, this ethic translated directly into the crafting and production of goods. ‘Journeyman’ meant you had worked hard and paid your dues, “made the journey,” so to speak. Yet the goal for some was the title of Master.

Today, these values are the exception.

We in Western society have largely become “observers” rather than “doers.” Atlas has indeed ‘shrugged,’ as in Atlas Shrugged, by Ayn Rand. I believe that the decline in appreciation of Craftsmanship is at the root of this trend, and that this trend must be reversed for us to survive.

I also believe that we all innately share a love and appreciation of fine craftsmanship, but most do not have a reference point or access to examples of it, which is why the Joe Martin Foundation and the Craftsmanship Museum is so timely. It is found on the internet, no less—the very existence of which I believe has drawn so many away from “making things,” and instead vicariously experiencing what others have chosen for us, in lieu of us identifying and pursuing a unique personal journey.

We usually associate craftsmanship with “model making,” but of course, there are master guitar and violin makers, woodcarvers, clock and watchmakers, instrument makers, and yes, even master software writers! However, almost all craftspersons are solitary folks, simply because “making things” is by nature a solitary activity. We toil quietly in our shop or at our workbench, music often playing softly in the background. We immerse ourselves in our work. Then, we gather together to share and show, thus bringing our work full circle for validation and to complete the journey.

The Challenge

I believe the single greatest challenge we face is simply identifying budding craftspersons in the first place, so that they may be encouraged along their path. I am referring primarily to the metal and woodworking disciplines. It used to be easy. Those of us over “you-know-how-old” had access to the Industrial Arts early in school. Printshop, Metalshop and Woodshop were my favorites. These classes offered us early exposure to options that in many cases translated directly into the job sector. We were the “geeks,” as many of us well remember!

We may have pursued other career paths, but at least we know these options exist, and often return to our “first love” later in life, while some of us followed our heart into a lifelong career.

“Shop” is not taught anymore, or at best, rarely. Lathes, mills, table saws and sanders have all been tossed out in favor of computer classrooms. Music and dance is following the same path as most craft oriented curriculum. Why is it that when funding becomes tight the Arts are the first to suffer? There are few teachers qualified today to teach the mechanical arts, because they themselves never had the opportunity to explore options, and society has decided that making things is for “other people”—our focus today is to create and manage “intellectual property.” Just wait ‘till the fuse blows!

The second challenge is to relate craftsmanship, or the Art of Making Things, to the computer age, in competition with video games, blogs, and other forms of passive participation. These are here to stay, and we must adapt. And we can! This website is just such an effort, and off to a grand start, I must say.

I was at a Guitar Center last week (I’m also into music) and met a young man in his late teens. He was working on crafting his first guitar, and researching sound holes and how other makers had designed them. He got his plans on the internet. He located his wood and tools on the internet. He had obtained instructions on the internet. Now, he needed to ‘see’ examples by noted makers, make notes (no pun intended) and snap a few photos on his cell phone. His goal is simple- to become a Master Luthier. I’m sure he will, because he is passionate about it, and willing to invest the time and effort necessary. Needless to say, I encouraged him!

Close-up views from Bill’s CAD rendering of Joseph von Fraunhofer’s Great Refractor Telescope.

I have referred often to young people, but of course, age is not the criteria. Passion is. However, access to the necessary tools is a serious impediment, with no easy answer. I think that, if a person is interested, they will find a way to buy, borrow, rent or make the tools necessary. There are many inexpensive machine tools on the market. All they have to ask is, “Mom, can I have a lathe for Christmas?” When I was fourteen I received a commission to cut gazillions of pieces of N-Gauge track for a Union Pacific promotion, so I bought a Unimat with a saw attachment. “On time”—my mom co-signed the promissory note. I paid it off in three months. My mom understood me well! I used that Unimat for many years.

An important option is your local Junior College. Many have non-credit programs and facilities well suited to the budding craftsman, often at very low cost. In California it’s called ROP, or Regional Occupation Program (we call it Retired Old People, which of course is not true!) designed to retrain or upgrade folks into new professions. This is how I first studied SolidWorks® CAD design, both beginning and advanced. I also helped out as a teaching assistant.

What Can We Do Now?

- Share our interests and expertise with others, in the hobby press, our local newspaper, regional magazines, on local television. Many of us are shy, but, hey—let’s get it out there!

- Get together more often! Search out others of similar interests and get together for coffee (or whatever), say once a month, to share our latest-and-greatest. Form a club if you want, but no need to be so formal.

- Share with the public. Display your work at the local library, with references to available literature. Use photos. Spend a few hours answering questions for the many kids that will ask them!

- Share with the public. Again! Every community has a “street faire” or block party. Ask for free space to set up a tent and some tables, get your friends together and share your work. With appropriate sticky-finger barriers, of course.

- Share your enthusiasm! Keep your eyes open for that young person of any age who expresses an interest or wonder, and encourage him or her to follow their dream.

- Mentor. If your skills, disposition and time allow, mentoring another person is immensely rewarding, and I truly believe our highest calling. I mentor several, all by email- we have never even met! I have been blessed in my career by several mentors, and fully intend to repay that debt!

Above all, follow your own dream and reach for perfection, for, like Pied Piper, others will follow…

—Bill Gould