Builder of the “Great Wooden Railway” in the Netherlands

Introduction

When it comes to model railroading, working in 1/25 scale is a bit unusual. It’s not quite the same size as the popular gauges of 1/22.5 (G gauge, LGB), 1/24 (half scale), 1/29 (G gauge Aristocraft/USSA Trains), or even 1/32 (#1 gauge). Even more unusual is that every single part of Roberto’s wooden railway is just that—wooden! That means the track, the switches, the trackside structures, the rolling stock, and the engines are all made from wood, along with everything else. Like most good woodworkers, Mr. Heijmans leaves the wood unpainted, using different colors and grains of wood to define the dark and light structures. This adds an additional challenge, beause mistakes cannot be covered up with filler or paint.

Naturally, some might wonder how a non-conducting wooden track could work for “electric trains.” Roberto’s trains don’t operate in the usual sense, where the power for the trains is transmitted through the rails. He has devised a different strategy altogether.

For the Great Wooden Railway, Roberto came up with an ingenious system using battery powered electric motors in the engines, and a series of magnetic or operator-controlled switches around the layout. These switches control where the trains stop, and when they can go. Electronic circuit boards control acceleration and deceleration, creating a realistic operational appearance. The layout is occasionally set up at train shows where it usually makes a huge impression. Roberto’s woodworking is very precise, and handsome. The sheer variety of engines, cars, and structures is mind-boggling. Below, Roberto tells his own story on the origins of his Great Wooden Railway.

A “Railway Virus” Passed From Father to Son

By Roberto Heijmans

I was born in 1953 in Raamsdonksveer, a small village in the south of the Netherlands. It was my father who gave me the railway virus—he built my first layout when I was about 4 years old. It was a simple O-gauge layout with a Hornby clockwork train. I quickly found it boring to see this train riding around in circles, so he started a new layout with a Tri-ang HO scale train. This layout grew bigger and bigger, and we eventually changed to Fleischmann HO stock. This lasted until I was about 16 years old, and then other things, like girls, became more interesting.

My interest in model railways faded somewhat, but it was never gone. Years later, I married and had two sons. One day at a bargain market I saw a plastic train set that ran on batteries, and I immediately bought it for very little money. The track was 5 centimeters wide, and the train and two cars were about 1/25 scale. It was a nice toy to play with for my kids, but soon the oval track started getting boring for them, as it had for me in my youth.

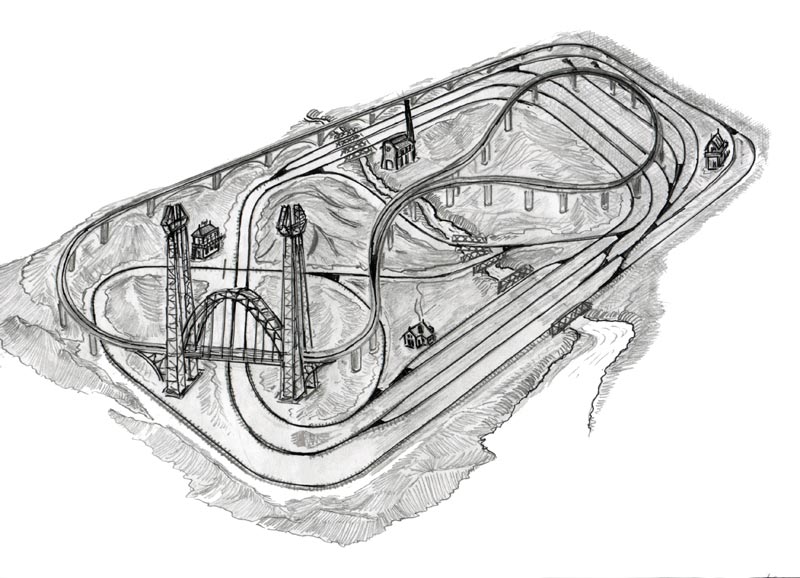

A sketch of the basic layout of Roberto’s Great Wooden Railway. The sectional track and switches allow for different layouts to be built.

Why Not Make It Myself?

A thought came to me: “Why not make more track myself?” I started experimenting, and after a while I had my first piece of track. Track width was 5 cm, and a length of 100 cm. This became my standard straight track. Of course, I also needed curved track, so I constructed one piece with a radius of 130 cm. I went on to make fixtures to build the different track pieces I needed, including switches and crossings.

Meanwhile, I felt it would be great to construct my own carriages, and I started drawing. I purchased a piece of plywood, and after some weeks I had my first self-constructed carriage body.

In those days, I worked at a factory where there were lathes. So I asked a colleague of mine if he could make me some wheels that would have the same dimensions and flange angle as the wheels from the plastic train. He did so, and I was then able to construct the under-frame. Once I put the parts together, I had my first project finished.

After this initial success, I decided to build a real locomotive, and I took my first little Tri-ang Dock Shunter (switcher) as an example. This took much longer to construct, but at the end I had a running locomotive, and very proud I was.

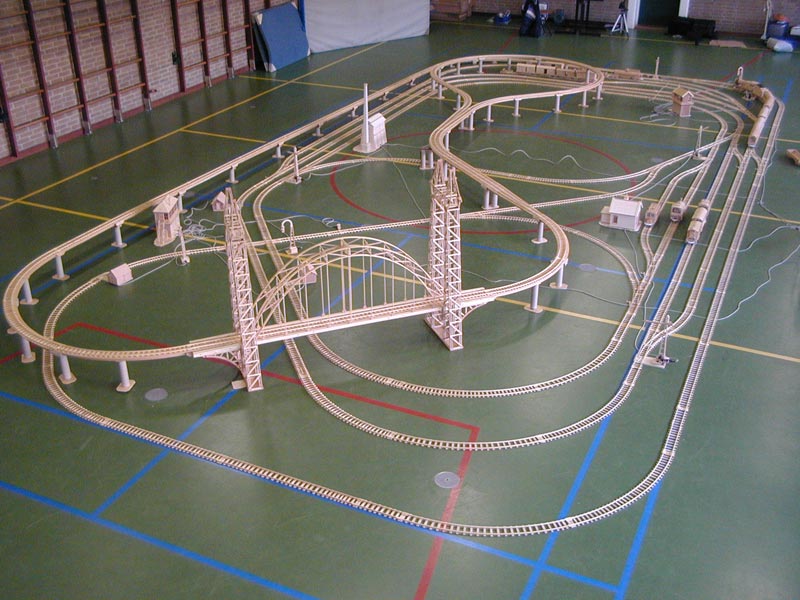

This image shows the bridge structure that Roberto built for his remarkable model railway. With Roberto in the frame here, viewers get a sense of the large scale of this project.

Providing Power to Electric Trains on Wooden Tracks

Then came the question of providing electric power. I learned that the batteries used in emergency installations were perfect for my trains. They have 12 volts and 7 amps, so they are very powerful. In the case of a small locomotive, they can be put in a carriage behind the loco, or when the loco is big enough, the battery is placed inside it. This gives the loco extra power because of the weight of the battery* (2300 grams).

I have now been doing this hobby for about 14 years, and during these years I’ve improved my skills and purchased machines such as a lathe and jigsaw. I currently have 16 locomotives, and about 80 carriages. Total track length is about 350 meters (1138 feet), and there are about 40 switches, a few bridges, and some signal houses. Once every year or two I am invited to a railway show in the Netherlands or Belgium.

So that all the trains run without problems, there are some simple electronics built in. Each loco has a micro-switch under its chassis, or bogie, that is activated by a small plastic strip between the rails, which is electronically moved up or down. These stopping-places are activated by reed contacts, which themselves are activated by magnets under the train (automatic), or by the switchboard operator. All the locos have built-in acceleration and braking electronics, so starting and stopping is quite realistic.

*Note: The weight that a locomotive can pull is limited by power and traction. Once an engine has enough power to spin the wheels, the only way it can pull more cars is to add more weight over the drive wheels—thereby increasing the coefficient of friction.

Photographing Students by Day, and Building a Railroad by Night

My full-time profession is being a school photographer, so every day I go to a local school to take photographs of the children and their teachers. It is a very pleasant job, and I like it very much. In the evening when I get home, I have time again to do some work on my railway. I have a nice workplace in my barn which is 3.5 meters (11 feet) wide, and 7 meters (23 feet) long. It has a loft where I keep all the trains, tracks, and structures.

—Roberto Heijmans

Watch a video of Roberto’s locomotives in action on the Great Wooden Railway.

Additionally, view more photos of Roberto’s incredible Great Wooden Railway.