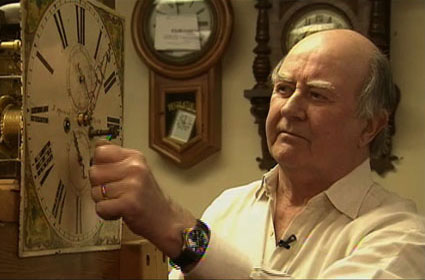

Known as “The British Clockmaker,” He Breathes New Life Into Old Timepieces

“Working with love and precision, Ray Bates sets antique clocks ticking again—and breathes some life into an age-old craft: ‘I call myself a clockmaker, but in reality what I do is reanimate,’ says Bates matter-of-factly. ‘Clocks are close to living things. The way the original makers constructed them predetermines how they will act, so while they may not be a living entity, they represent the ongoing creation of their makers. It’s my job to get inside the minds and hearts of the original makers, to be in communion with them, to make their works live again.’” —Boston Sunday Globe Magazine, 1995

From a Teenage Interest to a Lifetime of Horological Craftsmanship

Ray Bates is a traditionally trained clockmaker who brought his craft and training from Great Britain to the United States. When Ray was 16, he had a science teacher in high school who collected watches and dealt with a watch repair shop in Edinburgh. The teacher learned that the shop had an opening for an apprentice, so Ray went along for the interview. He would ultimately get the position, and wound up serving a 5-year apprenticeship with the R.L. Christie clock making company. Ray’s training there took place concurrently with his studies in mechanical engineering at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. These pursuits culminated with Ray’s graduation as a Craft Member of the British Horological Institute of London (CMBHI, now usually shortened to MBHI). In 1952, Ray achieved Master status after building his own clock completely from scratch.

After two years in the RAF as an instrument specialist and photo analyst, Ray started his own business in London. In 1957, he immigrated to the United States and started a business repairing clocks near Boston, in Waltham, MA. (Waltham is sometimes called “watch city” because historically it has been home to several well-known timepiece manufacturers). After eventually growing tired of city life, in 1964 Ray moved his family and business to a more rural setting in Newfane, Vermont. He remained in Newfane, and worked in what was once an old mill.

A peek through the window of “The British Clockmaker” shop in Newfane, Vermont shows many treasures.

Bringing Clocks Back to Life

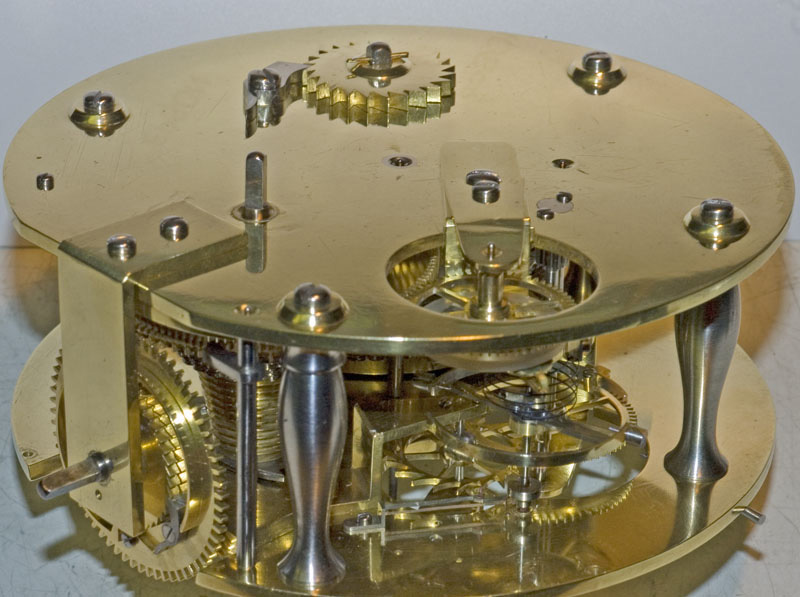

Now, as Ray notes, “You can’t buy spare parts for a 300 year old clock.” His job is to recreate worn or lost parts, and to do so in a way that prevents observers from ever telling the difference between new and original pieces. Only a tiny mark seen under magnification reveals the restored parts, along with the date of repair and remanufacture. Because these older timepieces were not mass-produced using interchangeable, factory-made parts, each element of a single clock is incredibly unique. Ray has a great deal of respect for the original makers of these clocks, and has dedicated himself to learning each aspect of the craft in order to duplicate the authentic methods and results. Ray doesn’t just bring a clock back to its original function, but also to its original beauty—restoring not only its ability to keep time, but also its value as a historical object.

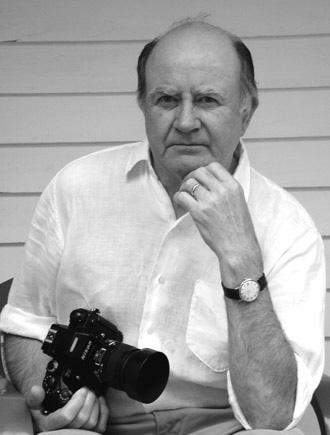

Ray is also skilled as a professional photographer—a craft that he learned from his job in the RAF. He took most of the photos on this page, and ran a full time professional photography business alongside his clock work for some time. Ray has had photos published in National Geographic, Vermont Life, Yankee, and some in-house publications. He is also a member of the American Society of Media Photographers.

A Combination of Modern and Traditional Tools

When it comes to work, Ray and his son have separate shops (which makes for good father/son relations). Both shops are well equipped, and have extensive libraries. The shops contain some traditional small watch and clock makers’ lathes, along with more contemporary equipment. These lathes include a Boley lathe, a Boley & Leinen lathe, a Derbyshire Model “A” Instrument lathe, and a South Bend 10″ “heavy” lathe for larger parts. For intermediate work, they have a Sherline lathe. Ray has also modified a Hardinge horizontal milling machine, and fitted it with the vertical head from a Bridgeport mill. The pair would use that machine to make clock gears, or “wheels,” as clock makers traditionally call them. Ray is aided in the wheel making by a piece of equipment that clock makers of the past would have probably given an arm and leg for—a CNC (computer numeric control) indexer.

Being able to use CNC simplifies the gear making process significantly. It eliminates the traditional indexing plate, with all its holes and indexing finger, and replaces that with a stepper motor driven rotary table. Ray simply enters the number of divisions (teeth) needed on the electronic keypad. Then, each time he hits the “Next” button, the table indexes the gear blank to the next position so that a new tooth can be cut. This machine is the brainchild of the self-styled “crackpot inventor” Bryan Mumford, and is manufactured by Sherline Products. Many of Ray’s processes are done using traditional tools and/or methods in order to achieve the authentic look. However, this is one area where modern equipment does the job more accurately, with less chance of error, and without compromising the integrity of the finished part. Ray is not hesitant to adapt modern methods where the results justify them.

However, there are still some processes which are done almost exactly as they would have been three to five-hundred years ago, when the clocks were still “new.” This includes things like engraving and plating portions of a clock face, restoring numbers or markings, or hand filing small parts to fit. Each unique part dictates its own method of repair or restoration.

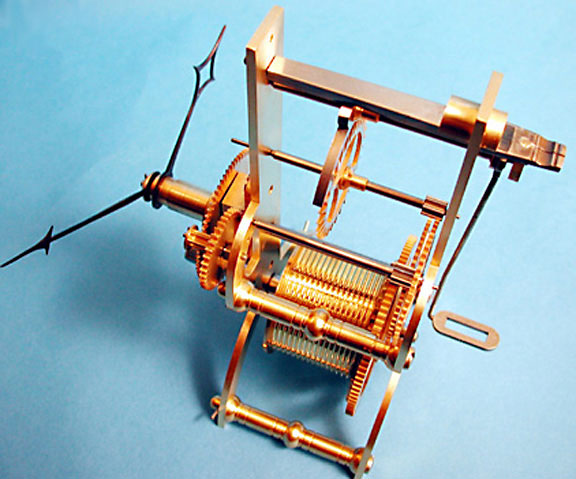

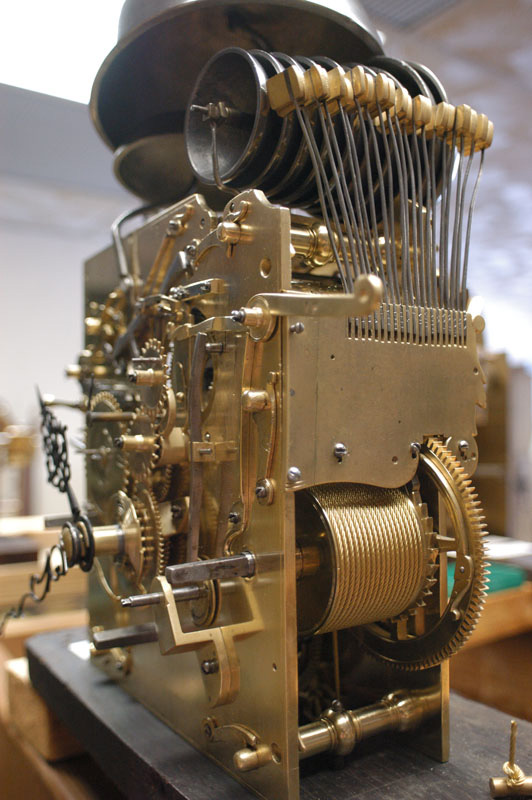

This is the multi-tune mechanism from a Dutch musical clock. It plays several tunes on a nest of bells. Both are from the 18th century.

Fancy Movements and Music Boxes

Now, it should be noted that Ray didn’t just repair and restore the timekeeping function of these clocks. Many of the clocks include complicated and ornate functions—or “automata”—which add an element of entertainment to the otherwise mundane time keepers. These automata take different forms, like doors opening on the clock, figures popping out and marching by, birds singing, and so on. Expensive clocks of the past incorporated many such functions, and were probably some of the most complicated and mechanically sophisticated devices manufactured at the time. Over the years, some of these functions may cease to work due to accidental damage, incompetent repair, or lack of proper cleaning and maintenance. Being able to understand each automata, and to replace missing or broken parts takes a true understanding of the tradition. This kind of work requires an in-depth knowledge of gears and mechanical movements. There are no blueprints or owners’ manuals that can be consulted for these old timepieces. Ray must simply study them until he can determine what parts may be missing, and then figure out what new parts might enable the automata to return to its original function. Ray’s website includes a number of photos and videos of some of these astounding automata in action.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the field of horology (the study of time, and time keeping devices) requires a high level of craftsmanship, particularly when it comes to making and repairing timepieces. This is especially true for older watches and clocks, which means that anyone trying to repair them should have at least an equal level of skill in order to bring them back to original form. Ray estimates that at least half of the work that he does is to redo previous attempts at repair by amateur tinkerers and hobbyists, who usually have little to no skill or training. He also notes that his favorite projects are the most complicated, and that each day in the shop brings a new challenge. The challenge of the trade is something that Ray never grows tired of, and it makes each new day in the shop enjoyable for him.

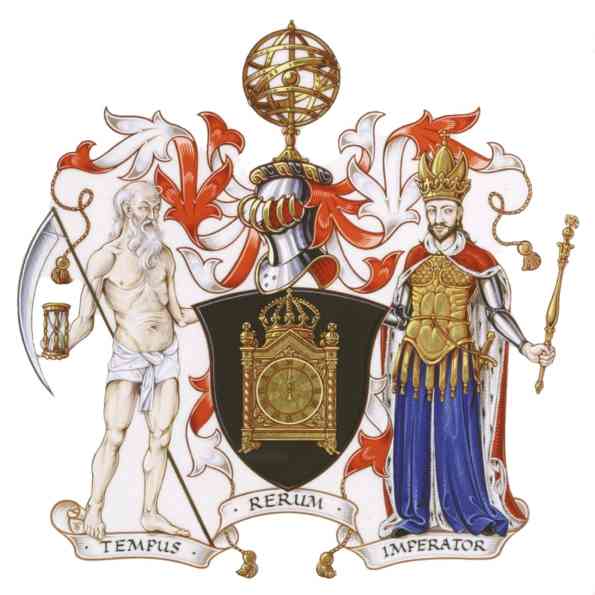

Ray Bates Inducted Into the British Livery Company

In April of 2010, Ray traveled to London to be accepted as a Freeman into the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. The Clockmakers Company was established in 1631, and it retains very close links to its origins in clock and watch making—both past and present. It is the oldest surviving horological institution in the world. To see some photos of the event, and Ray’s induction (under Joseph Raymond Bates), see The Clockmaker Newsletter from June, 2010.

The designation acknowledges Ray’s status as an internationally recognized authority on the repair, restoration, and conservation of antique clocks. Ray has more than 50 years of experience as a professional clockmaker, both in the U.S. and the U.K. He works with his son Richard, who has been trained through apprenticeship, to restore antique clocks from all over New England and Eastern Canada. The pair work with museums, conservators, private owners, and collectors of these priceless artifacts.

An Apprenticeship Program Founded Along Traditional Lines

In addition to his skills, Ray has also brought to America the traditional training methods which grounded his own work. In compliance with the state of Vermont, he started an apprenticeship program back in 1966. Since then, he has trained several apprentices, one of whom went on to achieve “Master” status. One of his more recent apprentices was actually his youngest son, Richard. After finishing his apprenticeship, Richard worked with his father for over a decade. In Ray’s words, Richard is “a natural.”

The Clockmaker’s Apprentice

For some time, Richard was making house calls to pick up and deliver clocks. This freed Ray up to continue running the business, and to devote more time to special projects and restoration work. Richard first began working for Ray in the 90’s, which started with his 4-year apprenticeship. The apprenticeship program that Ray employed was based on the British system which he himself trained under. Ray worked to develop his own program here in the U.S. in conjunction with the Vermont Department of Labor and Industry. The apprenticeship is an intensive program of training. It consists of hands-on experience in every aspect of clock making, along with research and theoretical studies. Only a handful of candidates have possessed the aptitude needed to be accepted into this program. In the 40 plus years since starting the apprenticeship, as of this writing, only five people including Richard have completed it successfully.

See more photos of Ray’s clock work.

Visit Ray’s website for more.