Below you can view more photos of Roger’s magnificent ships, and the building processes behind them. Captions are courtesy of the late Mr. Cole.

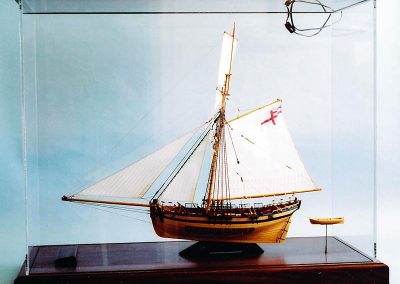

The Cutter Alert

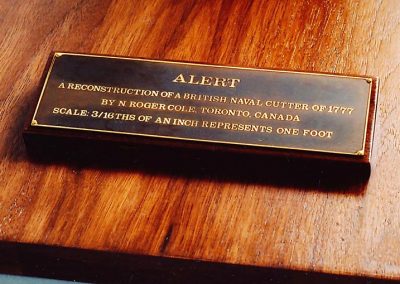

The Plinth-Mounted Nameplate

The etched, raised letter plate was made in my shop from brass plate, using Letraset® as a barrier to the etchant. Once etched, the process was stopped and the plate was polished. Then it was oxidized to an antique bronze finish, complementing the period of the original vessel. The plate is then protected with two coats of satin Krylon® paint. Regrettably, with the advent of computers, Letraset is now virtually unobtainable—so this approach is no longer feasible.

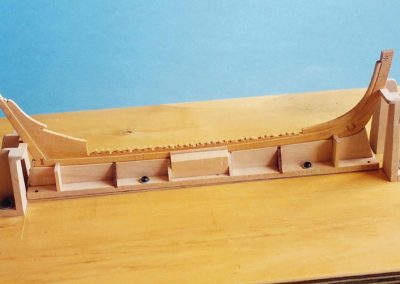

The Stem, Keel, and Sternpost Assembly

This view shows the stem, keel, and sternpost assembly, along with the aft deadwood. It also shows the apron inside the stem, mounted in the assembly jig. The assembly seen here was constructed with Columbian Boxwood, and includes details such as the holes for the forestay lanyard. All aspects of the assembly are glued and doweled using bamboo dowels. The jig holds the model absolutely true during construction.

Hull Framing and Ebony Wales

The hull framing is almost complete. Like the keel assembly, it was made from Columbian boxwood. The ebony wales were fitted with hook and butt joints, matching what was probably used on the original vessel. The wales were doweled using ebony dowels. The angle at which the hull is displayed matches the drag seen on the original vessel.

Port Side from Ahead—Planking Nearing Completion

Planking is completed up to the fifteenth strake. The sixteenth and final strake will be left off until the hanging knees for the deck structure have been installed. Once finished, the hull planking was polished and protected with a clear finish, followed with two coats of Renaissance™ Wax.

Positions for the Carlins Marked and Cut

Initial work on the deck structure started by locating and fitting the deck beams. In this view, the positions for the carlins have been marked and cut, and a few carlins and ledges have been installed. Once the deck framing has been completed, the deck will be laid using individual quarter-sawn Virginia holly planks. These will be doweled to the deck beam structure using holly dowels. This creates a deck that closely matches the appearances of a holystoned deck, where the caulking seams are to scale, and the bungs in the deck are unobtrusive—if not almost invisible.

The Plinth and Marble Insert

The mounting plinth and the sacrificial marble insert are installed to absorb the acids originating from the wood used in the baseboard, plinths, and model. The plinth was made from black cherry, painted flat black. It presents the model so as to show the waterline level. The slice of Boccaccino marble absorbs and neutralizes acid that would otherwise damage the materials used in the model. This is based on research done by Mr. Dana Wegner, Curator of the United States Navy Ship Model Collection. This view also shows the starboard planking to advantage.

Hull Planking

This view, with the model inverted, shows the symmetry of the hull and planking runs. The cutout on the port side reveals the framing, with the double or mold frames visible among the single or filler frames. The client requested that part of the hull planking be left off to reveal the framing.

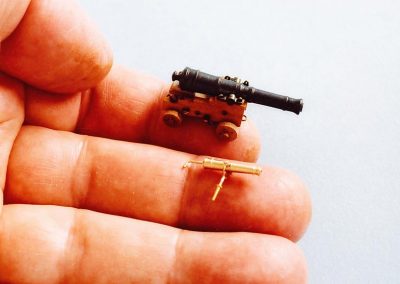

Armament

During her refit in Plymouth, in February of 1778, Alert’s armament was upgraded from ten four-pounders to twelve six-pounders, and twelve half-pounder swivels. The six-pounder gun shown here with one of the swivels was simply a trial horse, built to prove out the tooling and jigs used in the manufacture of the various components required. This included developing the pattern-turning system to allow accurate replication of the gun barrels. While the gun barrel shown here is close, the six-pounders used on the model were patterned precisely on the John Robertson pattern of 1776. This reflects what was probably used for her upgrade.

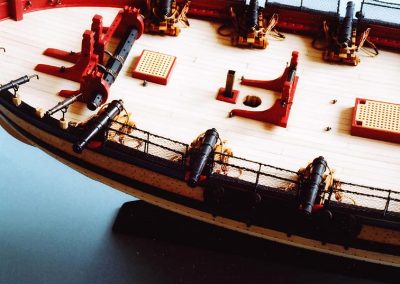

A Look at the Deck Detail Forward

Here we see the windlass details with the working ratchets and check pawls. Note the detail in the hammock nettings, guns and tackles, and the hatch and companionway gratings. Also seen here are the somewhat muted colors used on the model, reflecting the atmospheric effect that would have been evident had the original vessel been viewed from a distance.

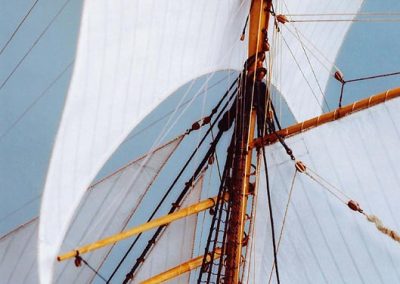

Headwork and Rigging From Forward

Seen here is a wealth of detail, including: the masthoops securing the mainsail to the mast; the wooden hanks securing the foresail to the forestay, which is cable-laid; and the lacing securing the topsail to its yard. Also visible high up on the shrouds, level with the lower edge of the gaff-jaws, are the shroud trucks. These are used to lead lines from above down the inside of the shrouds and ratlines, to belay on the shroud-mounted pin racks. Oddly, once a shroud truck has a line through it, it becomes a fairlead.

Masting, Rigging, and Sails From the Port Quarter

This view shows a wealth of detail aloft. The tablings, gussets, reef bands, and reef points can be seen on the mainsail. The mainmast hoops, foresail hanks, ratlines, and cable-laid shrouds can also be seen. There were no footropes on Alert—her spars would have been far too light to support the weight of a man. The spars, shown here finished with shellac, would have been lowered to the deck to replace or unrig sails, and to make repairs to equipment.

Masting, Rigging, and Sails From Starboard Bow

This view shows the mast with the luff of the mainsail seized to the mast hoops. It also shows the backstay tackles, and, just underneath the gaff jaws, the shroud trucks (fairleads). They are leading the various lines down behind the shrouds and ratlines so as to avoid interference with crew going aloft. This also provided a lead for the lines to the appropriate belaying pin in the shroud-mounted racks. The cable-laid forestay is clearly seen in this photo, along with the mouse and collar.

Overview of the Alert

This view shows the anchor cables leading in through the hawse. As the cables were too heavy to pass around the windlass drum, they pass underneath it en route to the hatch. A messenger would have been rigged to haul the cable. Lines can be seen belayed to cleats on the mast, and to pins on the shroud-mounted racks and windlass pin racks. Everything seen on the model was constructed in my shop: blocks, deadeyes, gratings, and shroud trucks were made of various woods. Anchors, guns, and all the metal fittings were made of brass, oxidized to represent ferrous metals. Cable-aid line, most larger line, and wire-cored line were laid-up on my ropewalk. Eye splices were made in all line over .021″ in diameter. Where required, line is served. Boltropes on the sails were hand stitched with 26 to 28 stitches to the inch. The nameplate and casework were also produced in my shops.

A Look at the Molding in the Sails

This view shows the molding achieved in the sails, while still leaving them on the soft side. The headsails are held out with wire-cored sheets. The mainsail boom and gaff are pinned in place due to the heavier sail and spars. The reef-points on the mainsail are tacked in place with a touch of glue. This view also shows the high gore cut into the topsail to allow it to clear the forestay and preventer. Also seen are the mast hoops securing the mainsail to the mast, and the wood hanks securing the foresail to the forestay. The use of hanks prevented the usual snaking where the forestay and its preventer were lashed together in a zigzag pattern.

Flag Details

The ensign on the model was made from raw Chinese silk, dyed with French dyes. This process, while long and at times tedious, produces a flag through which light can be seen. Alert would have carried a complement of five different size ensigns, or flags, ranging from her number one down through number four—plus a Jack. In size, the fly of the number one was generally about equivalent to the molded beam of the vessel, and the hoist was 5/9ths of the fly at this time. The other ensigns were proportional, and stepped down where the hoist of one became the length of the fly on the next smaller ensign. The Jack was equal to the canton of the largest ensign.

A Look Inside the Longboat

The longboat is fitted for sailing with the second thwart pierced for a mast. Eyebolts that support the standing rigging when sailing are fitted to the caprails. The third thwart is not fitted with supporting knees, which allows it to be removed when necessary—such as when transporting water casks, supplies, guns, or ammunition out to the cutter. The oars have been secured to prevent their loss should the boat be swamped while being towed.

A Close Look at the Longboat From Port

The longboat was carved from two blocks of Columbian boxwood, with a false keel sandwiched between the blocks. Once the outer profile was finalized, the three pieces were separated, holes for blind dowelling were drilled, and the two sides were hollowed out using rotary burrs and rifflers. With the inside carved out, the final keel and the two halves were assembled, and the inside of the boat was fitted out. The boat is in its towing position on the quarter, off the stern. In actual use, she would have been on a longer painter to keep the boat further aft. The rudder has been lashed to keep the boat tracking, rather than wandering with the risk of having her broach in a cross-sea.

Cutter Alert

Seen here with her sixteen-foot longboat rigged for towing, the longboat serves to provide a balance to the very long bowsprit. In all probability, Alert would have been forced to tow her boat while under way. It’s also highly unlikely that she could have lifted the longboat aboard, as the weight of the boat would have been too much for the light spars to handle. Even if the boat could be brought aboard, it would have seriously hampered Alert’s abilities in an unexpected engagement.

The Lizzie J. Cox

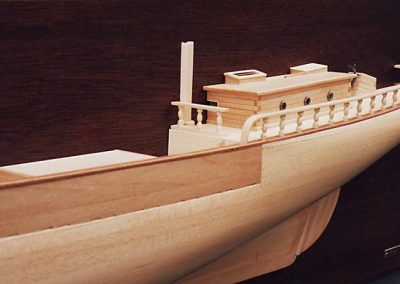

Overall View of the Lizzie J. Cox

Lizzie J. Cox, a Chesapeake Bay Bugeye, was built in 1905 at Fishing Island, Maryland by John Branford. The model was built to a scale where ¼ inch represents one foot. From the tip of the anachronistic longhead to the stern is about 19 inches. The model was awarded a Certificate of Commendation at the Mariners’ Museum Ship Model Competition in 1985, and was the subject of a fourteen-part series of articles in Ships in Scale magazine.

Bow and Longhead

The longhead supporting the bowsprit was a continuation of the days of figureheads. In fact, Cox did carry a small figurehead, that of an eagle head at the tip of the longhead. The anchor windlass seen here was manufactured locally and, while extremely durable, was not a finely-finished piece of machinery. The hawse holes and chain controllers are located ahead of the windlass and its heaver.

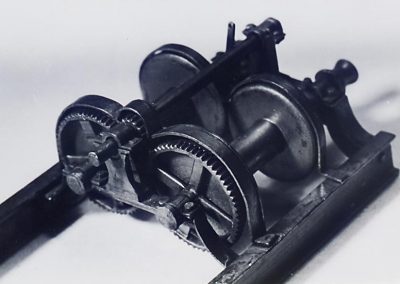

Anchor Windlass

This photo was exposed to highlight the detail in the windlass and anchor handling gear, with no regard to the exposure of the background. The whelps and rims seen on the barrels were protected with a resist, while the barrels were etched to remove unwanted metal. Once cleaned and polished, the whelps and rims were left standing proud of the barrels. The heaver is located on the front of the Samson post, while the handles are laid alongside the bowsprit heel.

Amidships View

This shows the oyster dredge gear aboard the Cox. The Hettinger winder, used to haul the dredges which are shown on either side of the fore-hatch, is located in the center of the photo. There is also rough sheathing laid to protect the deck from the abrasive oyster shells. On either side, there are heavy steel rollers over which the dredges were hauled aboard. The angled roller and bracket at the aft end of the horizontal rollers was there to protect the hull from the steel cable connecting the dredges to the winder.

Hettinger Winder

While extremely rugged and durable, the Hettinger winder was not highly finished. The machinery end of the model, without the end supports going to the left, is only slightly larger than the tip of a man’s thumb—from the quick to the tip, and about as wide. The finish is an oxide sold as Win-Ox, used in very weak concentration to be durable. Once oxidized, it was protected with a satin lacquer finish.

Bilge Pump

A version of an Edson diaphragm pump consisting of about twelve individual parts. While many of the parts were machined, others were sawn and filed to achieve the desired shape, e.g. the bowl with its lip. Virtually all my fittings are made from free-turning brass which, in this case, was given a bronze oxidized finish, although I am sure these pumps were primarily cast iron.

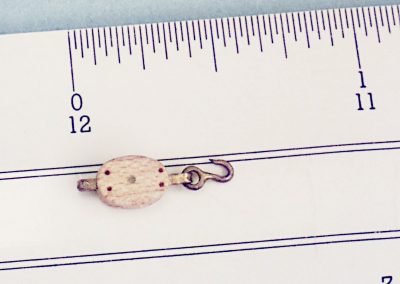

12-Inch Block

Among the faults seen on many models are incorrectly sized hooks. This block was scaled from a 12-inch block in my collection, and is correctly proportioned. The assembly consists of twelve parts, and is internally stropped. The finish on the metal parts are also oxidized and lacquered for protection. All my blocks above 1/8″ long are built up, and those below that are cut from solid wood.

The Stern and Push Boat

While Bugeyes were built as double-enders, the lack of space aft was a serious handicap. A local man then developed the squared platform seen here, and patented it, which solved the space problem aft. The push boat was used to get to and from the oyster beds, as the law demanded that oyster dredging be done under sail to protect the beds. The steering wheel is a Lake wheel, machined and etched in my shop.

The Santa Maria

Overall View From Starboard Quarter

Santa Maria, Christopher Columbus’ flagship on his voyage of discovery in 1492. The model was commissioned, and now resides in a corporate boardroom in Puerto Rico. It was built from plans prepared by Martinez Hidalgo, ordered from the Maritime Museum in Barcelona. This model was the subject of a six-part series of articles in Seaways Journal of Maritime History. The hull framing and planking are Columbian Boxwood, the deck is Virginia Holly, and the spars are Degame. The darker wood used extensively for trim items is Mountain Mahogany. Very hard and slightly brittle to work with, nonetheless it does an excellent job. The sails are 50-year-old tracing linen. All the rigging is linen line, laid up on my ropewalk and appropriately colored.

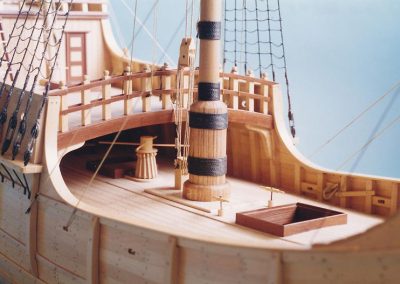

Quarter Deck View

This view shows the quarter deck with four Lombards—early versions of cannon. These, interestingly, were breech loaders. The external futtock riders seen here as vertical frames on the outside of the hull were reinforcing timbers. The mainsail carries a bonnet laced to the lower edge of the mainsail. This would be laced on when more sail area was required, or removed to reduce sail. The aft sail was a lateen. It was changed when tacking by casting off the lines, placing the lateen spar in a vertical position, and swinging it around the mast—thus re-securing the sail handling lines.

Sails, Rigging, and Flags

As mentioned earlier, the sails were tracing linen with the starch soaked out in lukewarm water, and many rinses. The sails were formed over carved wooden formers, and then airbrushed with a wet blend of Floquil clear finishes. When dry, the sails were taken off the formers and the back surfaces were airbrushed. The crosses on the sails were cut out of Frisket, which was applied as a mask and then airbrushed. The flags were made from raw Chinese silk, with the coloring done with French dyes.

On-Deck View

A look on deck, revealing the capstan under the front edge of the quarter deck. The ramshead block is immediately aft of the mast, which is heavily reinforced where it enters the deck. The Mountain Mahogany used for accent purposes can be seen to good advantage in this view. The main shrouds and their elongated deadeyes, and additional small bulwark details can also be seen.

The Beetle Whaleboat

Beetle Whaleboat from Port Side

This was a Beetle whaleboat, so-called as they were built by Charles Beetle—a whaleboat builder from New Bedford, Massachusetts. In fact, the name “Beetle” was burned into two places on the completed boats. This model was built to a scale where 1/2 inch represents one foot, and was the subject of a two-part series of articles published in Seaways Journal of Maritime History. The model was based on the last boat Beetle built. On completion, it was shipped to the Mariners’ Museum where it can still be seen today.

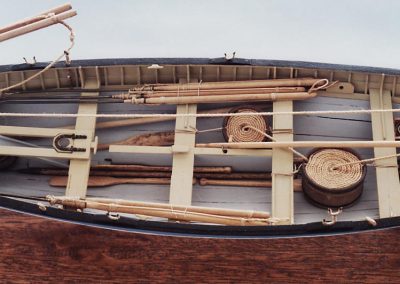

Midships and a Look at the Gear

The gear aboard a whaleboat was highly specialized. It included harpoons used to fasten to a whale, the lances that were used to kill the creature, but also the line tubs. In this case, the tubs were built with individual staves, as were the baling scoop and the fresh water keg. The harpoons, lance tips, boat knife, and hatchet head were made from nickel silver. This was oxidized to a soft patina representing age, and the edges were then polished to simulate having been recently sharpened.

Interior Detail

Whaleboats were ceiled inside, meaning that they were planked inside and outside the frames. This model is also an example of a painted model, as opposed to being polished Boxwood. At the right-hand end of the interior of the boat, the compass can be seen. It was required for situations where a boat lost sight of its parent ship. The compass in this model boat was gimbaled, as were the real ones. There are paddles in the bottom of the boat used when quietly approaching a whale on the surface. All of the equipment has been aged to represent usage.

Beetle Whaleboat

While this model was built to be displayed on a regular base and mounted on posts, Roger decided to see what it would look like set up on a simulated beach. This was done in his basement, on a piece of cardboard with a layer of sand. It had two different colored backdrops. The model is fourteen inches long.

The Benjamin W. Latham

Hull Framing on the Latham

The hull was framed in sugar maple, while the keel, stem and sternpost were of Columbian Boxwood. The planking rabbett has been cut into the keel and sternpost, along with the cutouts for the gudgeons. The top of the sternpost has been hollowed out to accommodate the rudder plugstock. The framing and deck have been faired, and are now ready for planking.

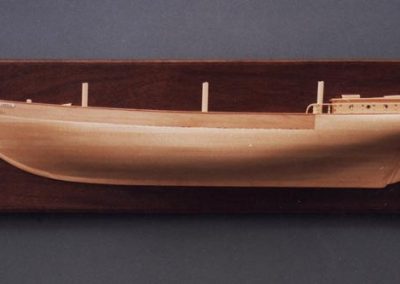

Benjamin W. Latham From Port Side

Built to a scale where ¼ inch represents one foot, this model was Roger’s first scratch built model after an absence of seventeen years. All fittings were also scratch built, including the stud-link anchor chain. The hull is planked in Columbian Boxwood, the deck is individually planked with Virginia Holly, and the spars are Degame—also known as Lancewood or False Boxwood. Planking has been left off to reveal the hull framing. Latham was the subject of an eight-part series of articles in Seaways Journal of Maritime History. It was awarded the Bronze Medal in the scratch built category of the 1980 International Ship Model Competition, held at The Mariners’ Museum in Virginia.

Deck and Seine Boat Detail

The planking thickness and framing can be seen in this view. The dory is stowed on deck, while the seine boat is shown secured to the boat boom. The deck is laid in individual holly planks which, in this case, were not dowelled. On-deck details include: the dip net used to lift mackerel from the seine boat to the deck of the schooner; and the barrels set up ready to clean the fish before they were packed for market. Including such detail in a Boxwood model is not traditional, but it is an important part of telling the story of the vessel.

Benjamin W. Latham From Starboard Side

Benjamin W. Latham was a small mackerel seining schooner built in 1902. Thomas McManus, of Boston, designed it for Captain Henry Langworthy, of Noank, Connecticut. She was built in the yard of Tarr and James in Essex, Massachusetts. Relatively small, she measured 72 tons gross. This view reveals her lines to advantage, along with the fact that her hull planking is trunnel or dowel fastened.

Half Models

Virago

A very small model with a hull length of 8 inches. It was modeled on a ferro-cement boat built in Nova Scotia. To represent the teak deck and furnishings, I used Red Gum—a wood commonly found in older buildings in the Toronto area for trim work such as door frames, moldings, etc. It finishes to a very good representation of a miniature-grained Teak. The paint finish was air brushed using Floquil finishes to create the desired effect, masking off the various parts of the hull while doing so.

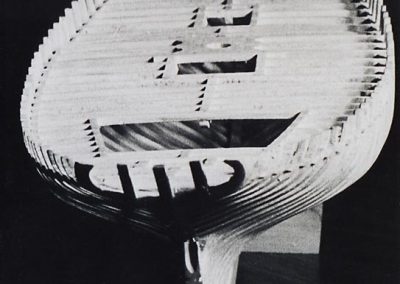

Novia Scotia Pinky (Circa 1875)

The term “Pinky” comes from the distinctive up-sweep to the stern bulwarks; this was known as a pink stern (or pinque—denoting its European origins). It also provided a protected seat-of-ease for the crew. Pinkies were used extensively on the Canadian and Northeast coasts, normally for inshore fishing. They were extremely seaworthy boats. This model is 13 inches long overall, excluding the bowsprit. It was laid up with 1/4 inch Basswood lifts, with each cut to its eventual shape. Once glued up, it was carved using templates to verify the true shape. The bulwarks were added later. The finish consists of four coats of white shellac, which was rubbed down and waxed with Renaissance wax—a conservators’ wax. The tiller was heat bent to the desired shape. As with all my name plates, this one was etched in my shop.

Sirius 28

This model was built to represent a production fiberglass boat, and is 14 inches long. The model was laid up and carved in the traditional manner from Hard Yellow Poplar. This is a beautiful carving wood, which cannot be used for naturally-finished work as it has an objectionable yellowish hue. However, it is superb for work that will be painted. The finish consists of 14 hand-rubbed coats of lacquer, with the different colors blended so as to avoid having the traditional raised edge where one color begins or ends. When a hand is run across the side on this model, there is a continuous smooth finish.

Edith Cavell, a Tern Schooner

Edith Cavell was named after the WWI nurse. This was a large schooner, and the hull length of the model was about 26 inches. She was also laid up from Basswood lifts that are ¼ inch thick, with each lift or layer cut to its shape on the hull. Once glued up, the hull was carved and checked with templates to ensure accuracy. Cavell is fitted out beyond the normal half-hull with turned stanchions (individually fitted), a half-wheel, and three stub masts.

Edith Cavell, a Tern Schooner

The tern schooners were all Canadian, and had all three masts exactly the same height—hence the term tern, meaning three. This hull was finished with a blend of three coats of clear Floquil finishes. It was then waxed with Renaissance wax, and polished to create a soft protective sheen.