Builder of the “Do Nothing Machine,” Which Produces Nothing but Smiles

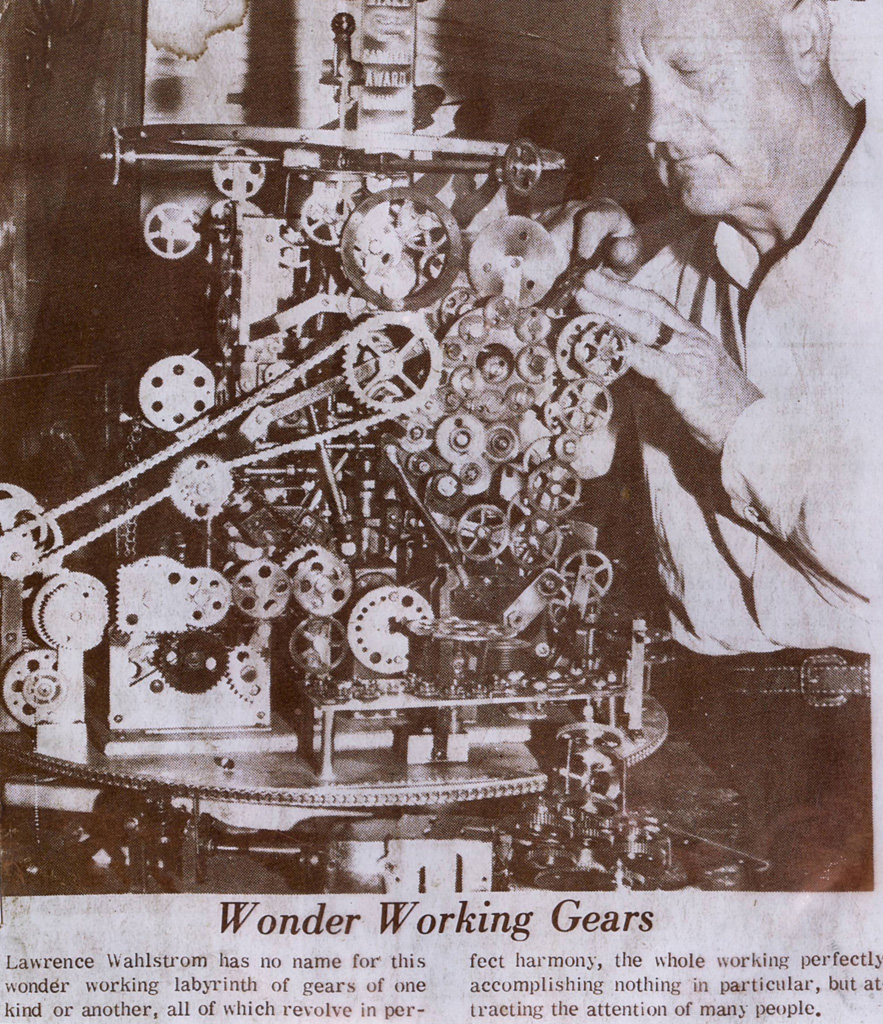

Lawrence Wahlstrom with his “Do Nothing Machine”. This photo was taken in the 1950’s, and published in an unknown newspaper. Earl Wolf would later become caretaker of the unique machine after buying it at auction.

A Clever Machine Reflecting a World Growing Ever More Complicated

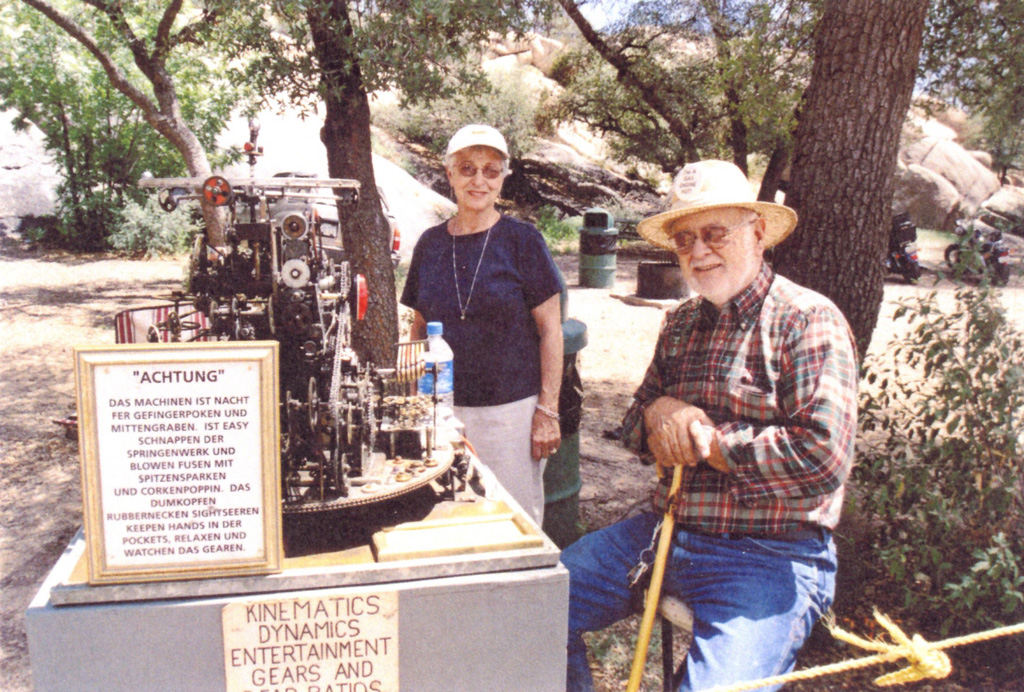

Mr. Wahlstrom’s Do Nothing Machine was purchased and preserved by Earl Wolf, and donated to the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum by his family, in his name.

According to an uncited newspaper article, around 1948 Lawrence Wahlstrom began to build his engineering marvel—the “Do Nothing Machine.” Mr. Wahlstrom was a retired clockmaker who also worked in the newspaper business, and for a telephone company. On top of that, for 40 years Lawrence was the caretaker and landscape gardener for a Beverly Hills estate. He always enjoyed tinkering with clocks, and had attended a clock school to learn about repair.

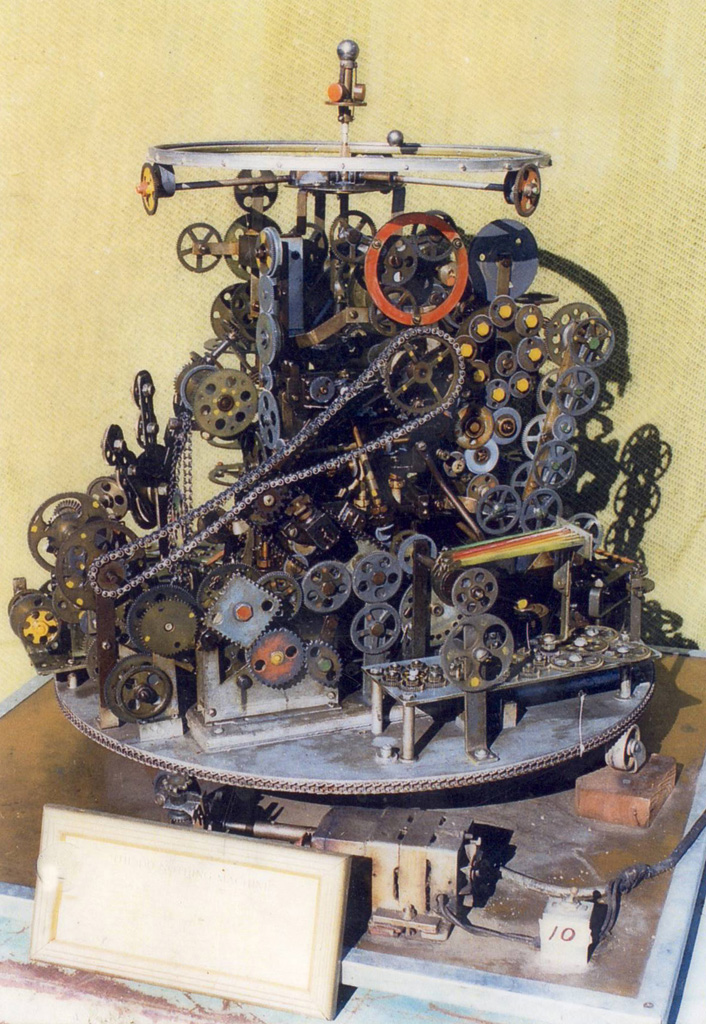

Somewhere down the line, Lawrence acquired a real fascination with gears. After coming across a surplus WWII bomb sight, containing a complicated cluster of gears, he got it working again. This would be the start of a continually growing project, with no immediate end in sight.

Lawrence also realized that people prefer to be entertained rather than educated, so he began adding more and more gears to this assembly over a 15-year period. The first known publicity photo of the Do Nothing Machine appeared in 1950. It would certainly not be the last, as Lawrence’s machine grabbed the attention of countless curious onlookers for decades—and continues to do so.

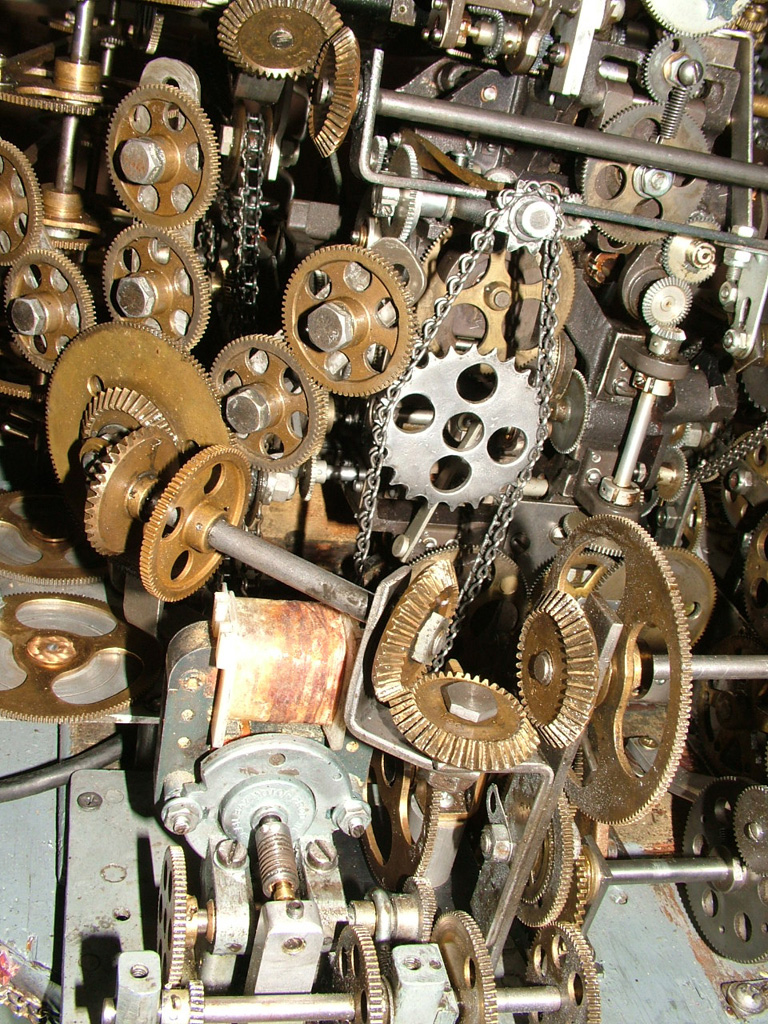

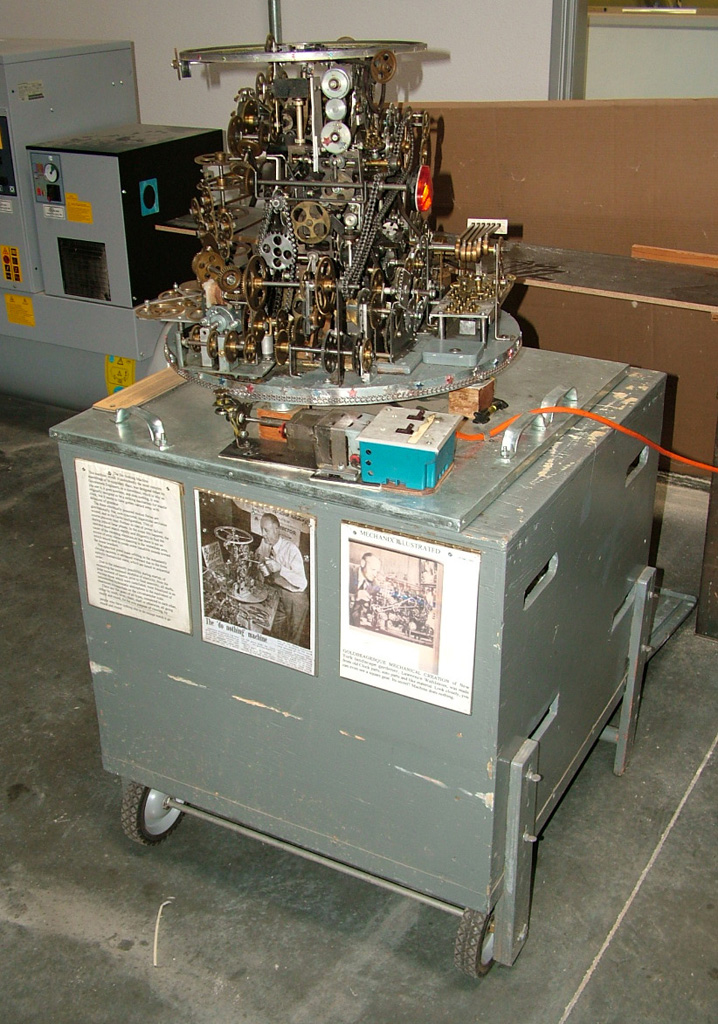

The Do Nothing Machine upon its arrival at the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum. Some work was needed to clean up the electrical connections, and restore some of the geartrains to running condition. Photos hardly do justice to this tremendous collection of moving parts, despite the fact that, as the name implies, it does nothing.

A Machine That Kept Growing—In Size and Fame

Over the years, the number of gears on Lawrence’s machine continued to grow. It reached either 744 or 764 gears in total, according to two separate accounts. Much like the general motion of the machine, the actual figure is somewhat fluid. It attracted a lot of media attention over the years, appearing in magazine articles and on TV shows.

In fact, Lawrence’s Do Nothing Machine was shown on both the Art Linkletter show, and the Bob Hope show. Additionally, the Wahlstrom family archive has a telegram arranging for Lawrence to appear on the Gary Moore show in November, 1954.

Additionally, Life magazine gave the machine a full page in the April 20, 1953 issue, and Popular Mechanics gave it a half page in their February, 1954 issue. In February, 1955 the Do Nothing Machine was also featured in Mechanix Illustrated magazine.

It’s safe to say that many newspapers and magazines documented the constant evolution of Lawrence’s unique, but materially fruitless machine.

One uncredited newspaper article, writing tongue-in-cheek about Lawrence and his machine, noted the following:

“This machine, which is undoubtedly the most complex assemblage of bi-cuspidary discs, was designed either by government engineers or a committee, which is why as you see it, it goes nowhere and does nothing. It was originally designed to be a striking mechanism for a mantle clock, but it seems to have gotten carried away with delusions of grandeur.”

“The three electrically powered motive forces are gravitationally free, non-syncronal, trapezoidal seclusion wound, and in the Delta configuration. This, of course, prevents total flocture in case of power failure during critical lunar phases. In the event this happens, the operator must search rapidly and diligently to find the cause of the escaping electrons, so that there is no an excess of stray electrons massing in the immediate area. This would tend to create some inaudible sounds toward the lower brackets.”

“The spherical metal mass orbiting in the redundantly circular raceway is advanced rearward due to the three epicylic framatoidal cams, which are timed in sequential order. There are 764 gears of all types connected to each other—either by tooth, lever, chain, shaft or otherwise. All of these going round and round for the sole purpose of viewing by people who have nothing else to do, except watch it go round and round.”

Now, Lawrence Wahlstrom often referred to his machine as a “Flying Saucer Detector,” or gave it other nebulous and facetious descriptions. His goal was to add at least 50 gears each year to the constantly growing project.

As noted in Popular Mechanics in 1954, “We all know someone who works harder doing nothing than most of us work doing something, but we can’t possibly know anything that works harder at nothing than a machine built by a California hobbyist. The machine has over 700 working parts that rotate, twist, oscillate and reciprocate—all for no purpose except movement.”

This close-up shows some of the kinds of gears and movements incorporated into the structure year after year. Keeping it all running after Mr. Wahlstrom passed away was the job taken on by Earl Wolf, who purchased, fixed and displayed the machine starting in about 2003. It was a favorite sight at fairs, engineering gatherings, shows, and club meetings for many years. Mr. Wolf never tired of keeping the story alive.

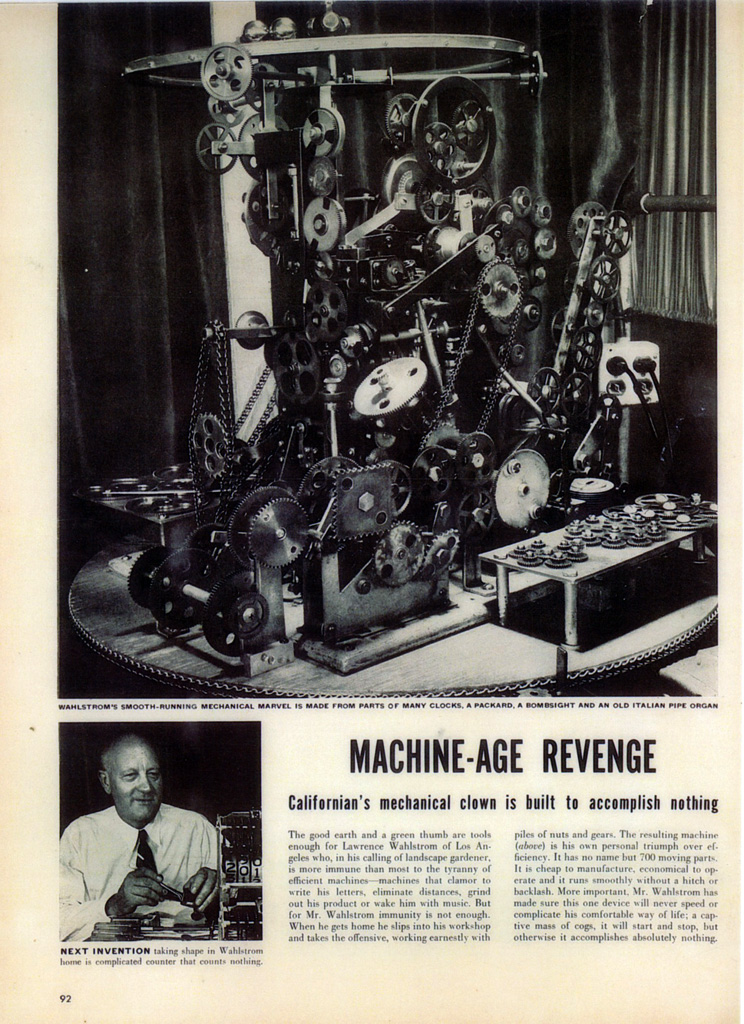

In 1953, the headline of the Life magazine article on the machine read, “Machine-Age Revenge—Californian’s mechanical clown is built to accomplish nothing.” The article goes on to say:

“The good earth and green thumb are tools enough for Lawrence Wahlstrom of Los Angeles who, in his calling of landscape gardener, is more immune than most to the tyranny of efficient machine—machines that clamor to write his letters, eliminate distances, grind out his product or wake him with music. But for Mr. Wahlstrom, immunity is not enough.”

“When he gets home he slips into his workshop and takes the offensive, working earnestly with piles of nuts and gears. The resulting machine is his own personal triumph over efficiency. It has no name but 700 moving parts. It is cheap to manufacture, economical to operate, and it runs smoothly without a hitch or backlash. More important, Mr. Wahlstrom has made sure this one device will never speed or complicate his comfortable way of life; a captive mass of cogs, it will start and stop, but otherwise it accomplishes utterly nothing.”

The Popular Mechanics article that featured Lawrence and his machine in February, 1954. The cover is shown in the second photo.

Earl Wolf Gives the Do Nothing Machine a Second Life

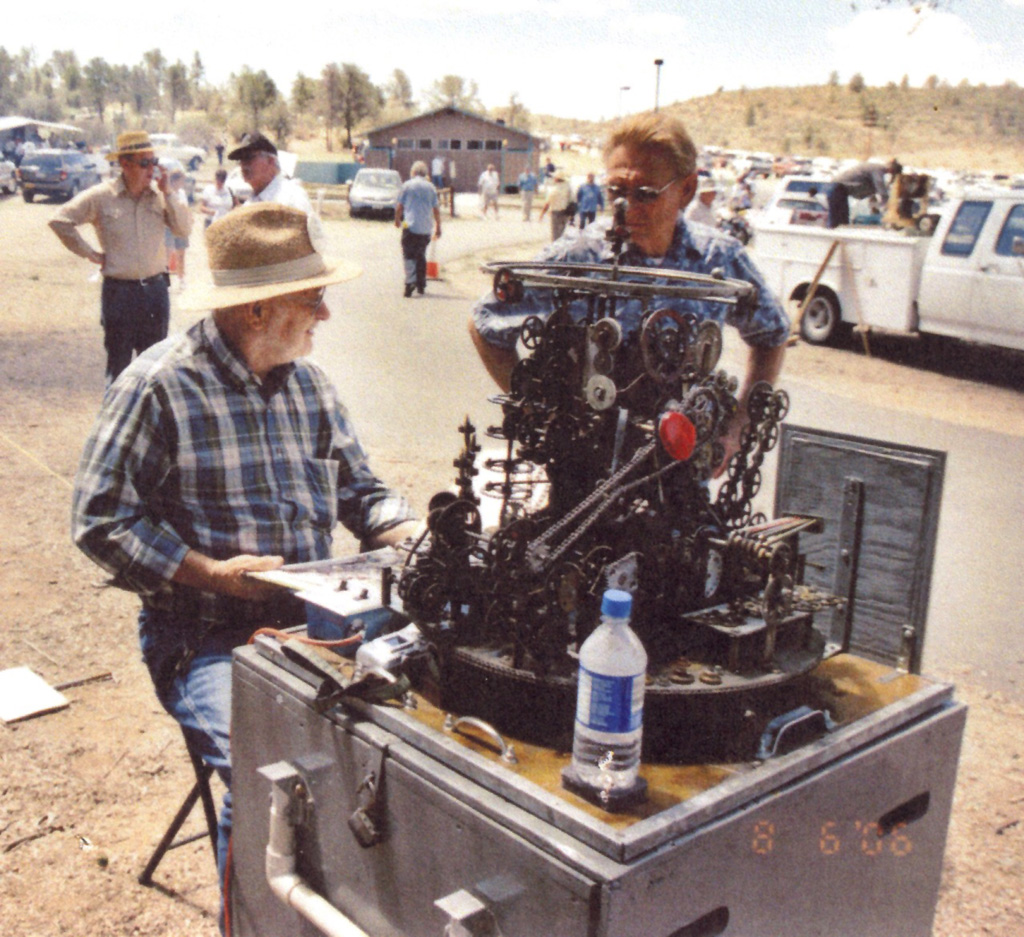

At some point, after the Do Nothing Machine came into the possession of the Antique Gas and Steam Engine Museum in Vista, CA, it was put up for auction. Earl Wolf purchased it around 2003, repaired it, and took it to several shows every year for the public to enjoy. The following article by Mark Duncan was published in the Yavapai Yellow Sheet newspaper in October, 2006.

Prescott Man’s Machine Does None of the Work

By Mark Duncan

Some folks spend their golden years doing nothing, but not Prescott’s Earl Wolf. He’s got a machine for that.

Wolf, a retired plumbing contractor, is a collector of arcane machinery. He has a tiny steam engine, a hot air engine, a solar motor that spins like the dickens in the Arizona midday sun, and a Dynavoice Piano Player (not a player piano) that sits on a keyboard and, driven by a vacuum cleaner motor, presses the keys on the commands of punched paper rolls.

But the jewel of his collection is without a doubt the 60-plus year old, one-of-a-kind, magnificent and wonderful Do Nothing Machine, which he picked up in an auction from the Antique Steam and Gas Engine Museum in Vista, Calif.

It was built by clockmaker Lawrence Wahlstrom of Los Angeles during a period of seven years starting in the late 1940’s. the machine has three electric motors that spin it on its pedestal while driving chains, sprockets, steel bars, a tiny taillight, and more than 700 gears in a flurry of activity that accomplishes absolutely nothing.

The machine, and Wahlstrom, had a flirtation with fame in the 1950’s, and Wolf has a scrapbook detailing more than 25 television appearances—including gigs on the Garry Moore Show as well as spots with Bob Hope and Art Linkletter.

From time to time, Wahlstrom called the machine a Flying Saucer Detector, or a Smog Eradicator. Obviously, it did none of those things—it does nothing but entertain, the inventor was prone to admit.

These days, Wolf spends several weekends a year going to fairs and festivals, where he and his useless device invariably steal the show. “It’s always the biggest hit at the show,” Wolf said. “People will look at it, they’ll stick their noses in there and study it, then walk away and then come back and study it some more.”

Truly, the softly whirring machine has a mesmerizing effect on an observer. Here’s a part of an oil pump from an old Volkswagen, and those little steel bars are from a World War II Norden bomb sight. There are square gears, round gears, even an oblong gear, a floating gear and the crankshaft from a linotype machine—as well as a ball bearing that plies an aimless path along a tilting metal race near the top.

And it breaks down—a lot. “The machine does nothing, but I have to work,” Wolf said. “I’ll show it for a day or for a weekend and then spend the next three or four days getting it running again.”

Despite having owned the machine for three years, Wolf is uncertain exactly how many gears it contains. The documentation lists 744 and 764, but Wolf is not about to try to count them. “Oh, God no, you can’t count them,” he said.

It’s about all he can do to keep the machine well lubricated—he’s become an expert in the properties of various brands of silicone sprays—and fix it when some part or another stops working.

“You just track it down,” he said. “I’ve worked on it so much by now that when I see something not turning, I pretty much know where to find the problem.”

Even though its heyday of television appearances is behind it, the machine still attracts admirers with a creative bent. At a show in South Dakota, Wolf said, a couple looked at the device for a half hour on Saturday, then came back the next day with a poem the man had written.

“He said he was up until three in the morning writing it,” Wolf noted. It read, in part: “A magnificent kind of invention. A wonderful thing to behold. The most beautiful thing in the world. It’s a Do Nothing Machine I am told.”

What is the value of a Do Nothing Machine? Wahlstrom built it for about $25 (Wolf recently replaced two sprockets for $33), and it last sold for several hundred dollars.

Wolf said he would certainly take $10,000 for it if anyone offered, but no one has. So he has a plan. Knowing the machine needs to go to a good home, where a mechanically-inclined lover of synchronized intricacy would give it the care it deserves, he plans to donate it to a young friend—once his own gears start to wear out.

Money isn’t really the object. “The thing has already given me a million dollars worth of pleasure,” Wolf said. So maybe it does do something after all.

Earl Wolf built a special transportation crate and display base for the Do Nothing Machine. It also served as a billboard to post photos, articles, and information about the machine for curious onlookers.

Preserved For Present and Future Engineers to Enjoy

In the machine’s present state, after being demonstrated thousands of times over the past 60-plus years—by both Mr. Wahlstrom and then longtime caretaker Earl Wolf—it’s a little worn, but still functional. A couple of the gear trains in the center of the mass have ceased to work consistently. However, the overall impression is still one that inspires both awe and cheer when seen in action.

The famous Do Nothing Machine is now on permanent display in the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum in Carlsbad, CA, courtesy of the family of Earl Wolf. It has been maintained and operated in its present condition, exactly as Mr. Wahlstrom and Mr. Wolf ran it. For as long as possible, the museum shop machinists will keep it running for visitors to enjoy.

Video of the Do Nothing Machine

Watch a YouTube video of the Do Nothing Machine was taken in the Craftsmanship Museum shop, with our machinist Dave Belt providing information.

Watch another YouTube video of Earl Wolf running the Do Nothing Machine.

Additionally, watch an older video of the machine when it was still shiny and new.

Summing up its function and purpose is the aforementioned poem, written in honor of the Do Nothing Machine, and presented to Mr. Wolf.

The Do Nothing Machine

By Keith Christensen, Tabor, SD

It’s wonderful, stupendous, colossal

It wakes up all of my loves

The most wonderful gadget ever

Now what would you say that it does?

It has big gears and small gears and levers

It has a governor too

This machine is downright exciting

I wonder what all it can do?

There’re seven hundred gears to amaze you

There’s even a flashing red light

Things go this way and that way and new ways

It’s just a most wonderful sight.

A magnificent kind of invention

A wonderful thing to behold

The most beautiful thing in the world

It’s a Do Nothing Machine I am told.

Our thanks to Dianna Moinet, Mr. & Mrs. Lee Stanek, and the family of Earl Wolf for the donation. Thanks also to Leo and Lisa Zugner at the Antique Steam and Gas Museum for restoring the machine and delivering it to the museum.