A Master at Building Steam Engines, and Showing Others How To Do the Same

Recipient of the 2005 Joe Martin Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award

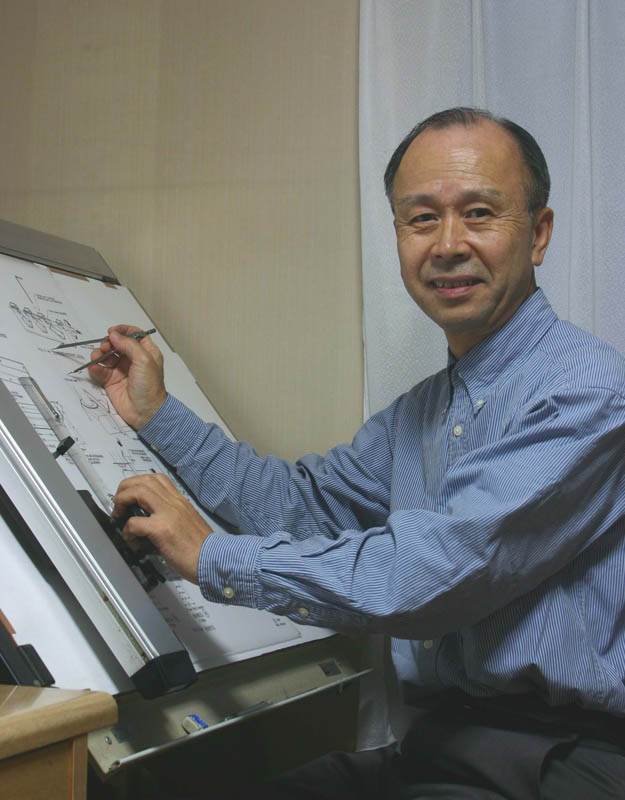

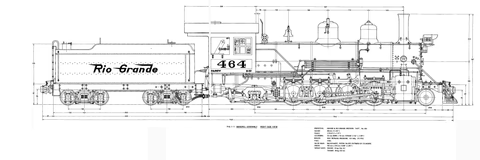

Mr. Hiraoka chose to hand-draw nearly all of his plans, because they have a warmth and personality that cannot be conveyed in CAD drawings. His drawings are an important part of relaying his steam engine plans to others—particularly because they act as a universal language.

Introduction

Mr. Kozo Hiraoka first came to our attention through his published books. These books have given Mr. Hiraoka a reputation as one of the key figures in live steam locomotive modeling instruction. In building these models, Kozo had to master many different techniques in metalworking and engineering. On top of that, he needed to successfully downsize massive prototypes to create models that not only faithfully represented the real thing, but also functioned in the same manner—despite size differences.

Additionally, Mr. Hiraoka has taken on the even more difficult task of documenting his work to provide instructions for other eager modelers. This involved making masterful mechanical drawings with ink, and providing clear technical writing. To make matters even more difficult, Kozo chose to present this work in his second language (English). We feel that Mr. Hiraoka’s accomplishments deserve special recognition because of both the enormity of the task he took on, as well as his masterful ability to pass his knowledge on to others.

A Career Working on Large Machines Includes a 200-Mph Railway

Kozo Hiraoka was born in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1937. He started his working life as a mechanical engineer, designing industrial boilers with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. With the rapid development of the chemical industry around the 1960’s, the company expanded their business to include engineering and constructing oil and petrochemical plants.

Kozo was involved in that work throughout his career. Each plant consisted of a wide variety of equipment and machinery. Kozo’s job involved the engineering and commissioning of oil and gas plants, mainly in the Middle East.

When Kozo retired at the age of 60, his employers requested that he continue assisting with several projects. As a result, in 2002 he was involved in the Taiwan Shinkansen Project—a 200-mph railway exported to Formosa.

Though Kozo was not familiar with high-speed railway technology, the project team persuaded him to join them. They explained that there were several tasks that could be managed by him. In 2004, Kozo was enjoying the engineering work of a real railway at the highest service speed in the world.

A Love of Model Engineering Goes Back to His Youth

Since he was a schoolboy, Kozo was attracted to models of airplanes and small gauge railroads. In his early thirties, Kozo realized his dream of owning a bench lathe with a 7” swing. It was at this point that he started to build live steam locomotives.

These working models satisfied Kozo for several reasons. First, he knew that the models would run with steam on the same principle as the prototype. Secondly, Kozo could fabricate all the parts himself. Lastly, the model could be run by riding on a passenger car. A critical issue that most model engineers must face is deciding how close to make the construction and performance of the small model to that of the prototype.

Because of the geometrical effect, the smaller the model, the more difficult its design will be. For example, on a model at 1/10 scale, the area is reduced to 1/100 of the size, and the volume reduces to 1/1000. However, air, steam, and other physical properties remain the same regardless of scale. Striking a balance between engineering challenges and running performance, Kozo chose 3/4” scale (1/16), or 3-1/2” gauge locomotives.

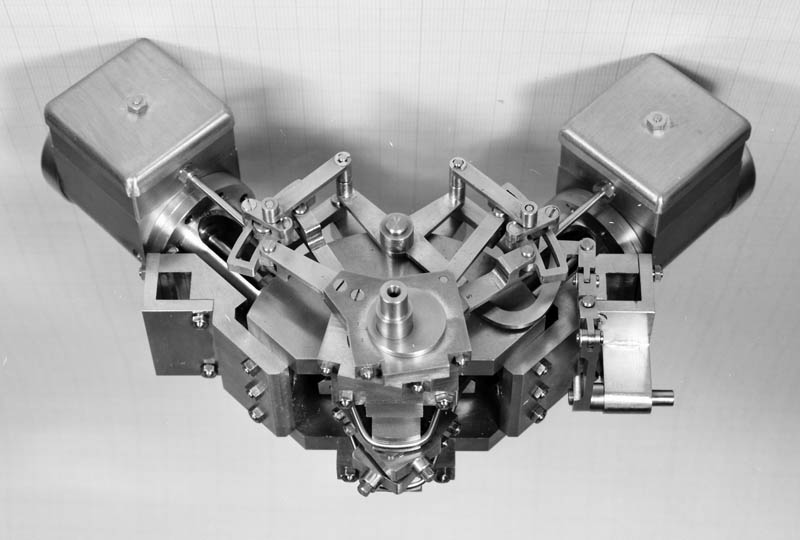

The V-type engine for Kozo’s scale model Heisler locomotive. Though photographed upside down, this angle shows the mechanism as it would more normally be seen.

Building Different Types of Locomotives

Among the many types of steam locomotives, the geared engines left the strongest impression on Kozo—including the Shay, Heisler, and Climax. These engines were invented in the US during a period when steam was the only big power available. These locomotives were designed to accommodate for one particular thing—running on steep, rough track. The engineers who designed the engines dedicated their efforts to achieving this required performance. As a result, each type of geared locomotive has a distinct personality.

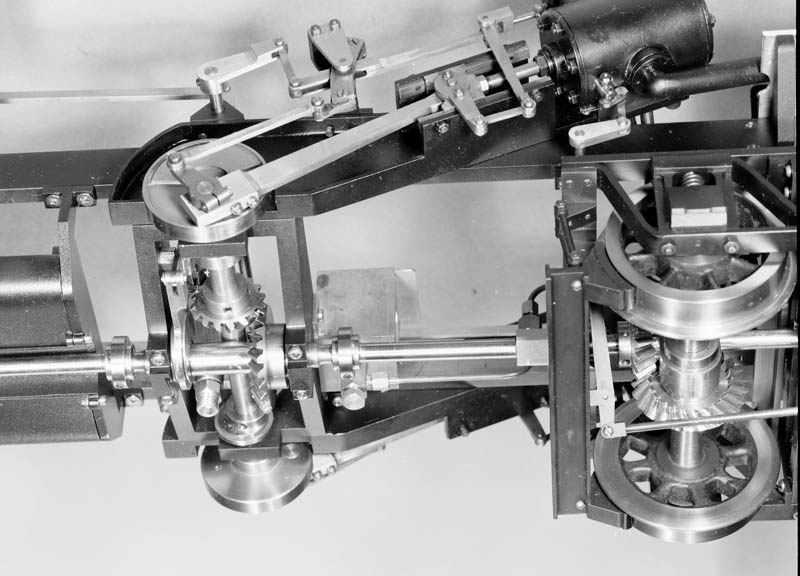

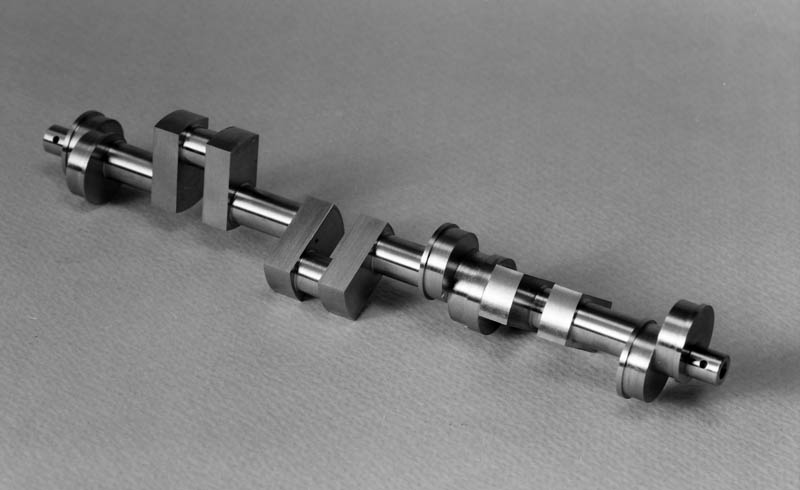

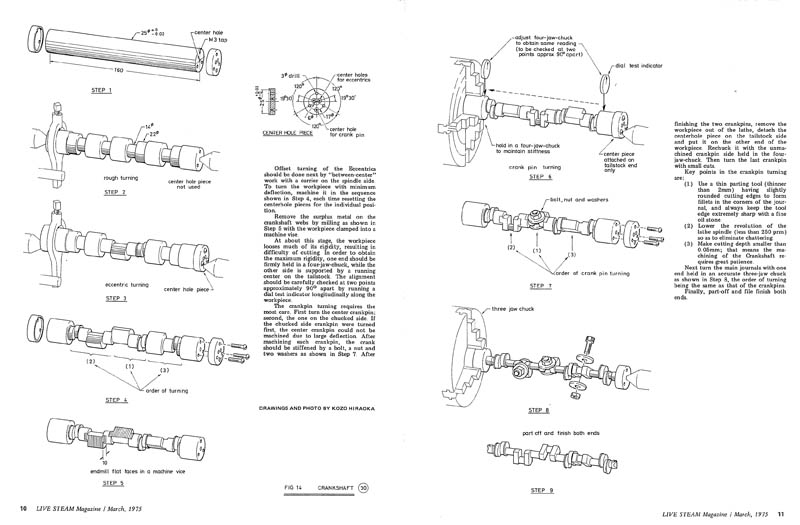

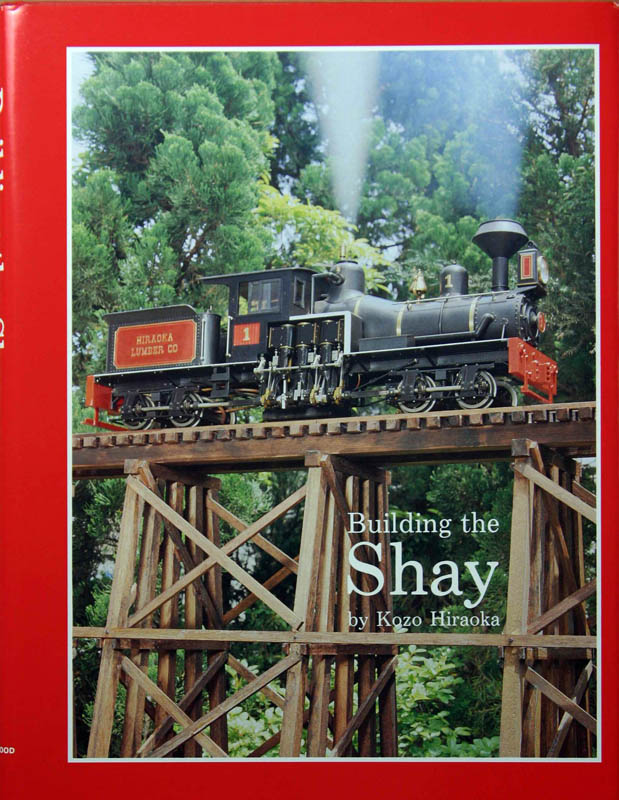

To build working models of these engines, Kozo had several obstacles to overcome. For example, the Shay locomotive (pictured below) had a crankshaft with ten different centerlines. It had three for the crankpins, six for the valve gear eccentrics, and one for the journals. Kozo developed a method to machine the single-piece crankshaft out of bar stock.

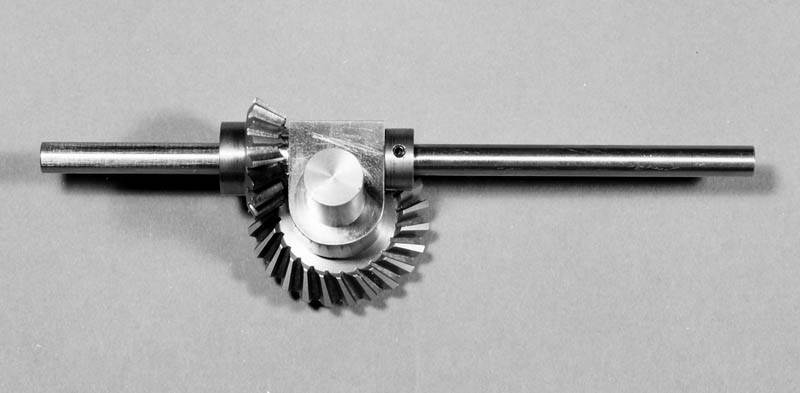

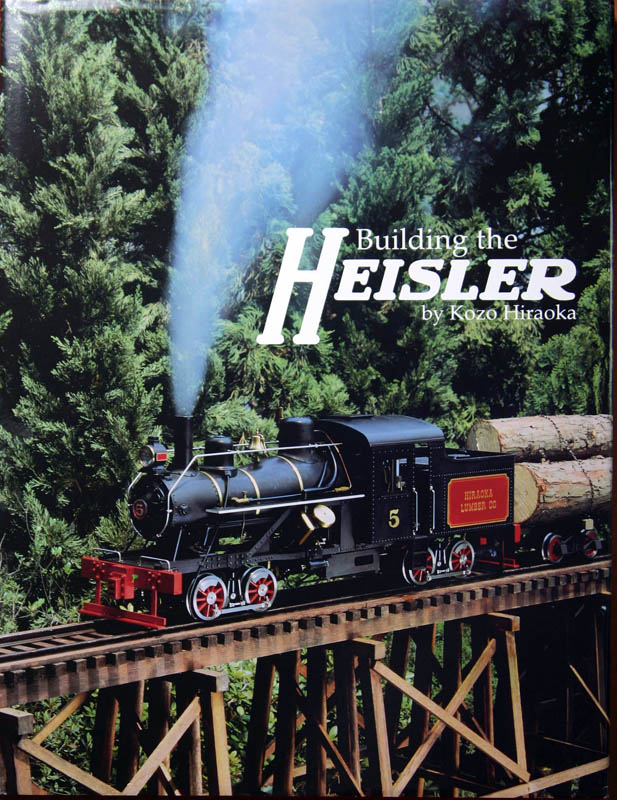

Similarly, the Heisler geared locomotive (pictured below) is equipped with a unique V-type engine. Its rotational power is transmitted through the line shaft to the farthest front and rear axles via bevel gears. In turn, power is transferred to the other driving wheels via slide rods. It can be said that the Heisler is a symmetrically balanced locomotive.

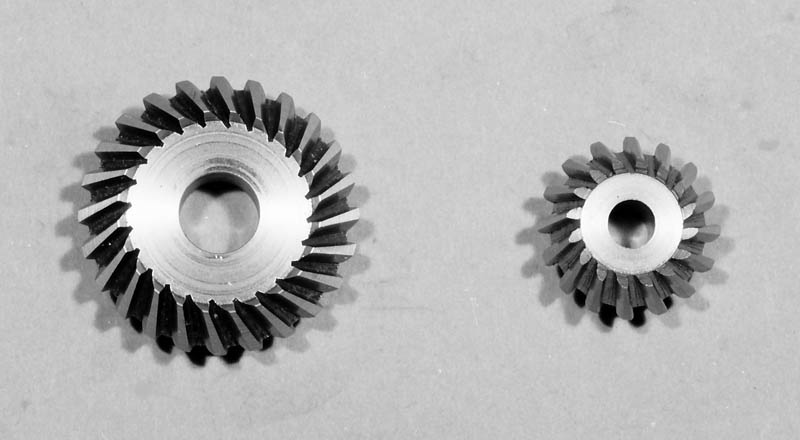

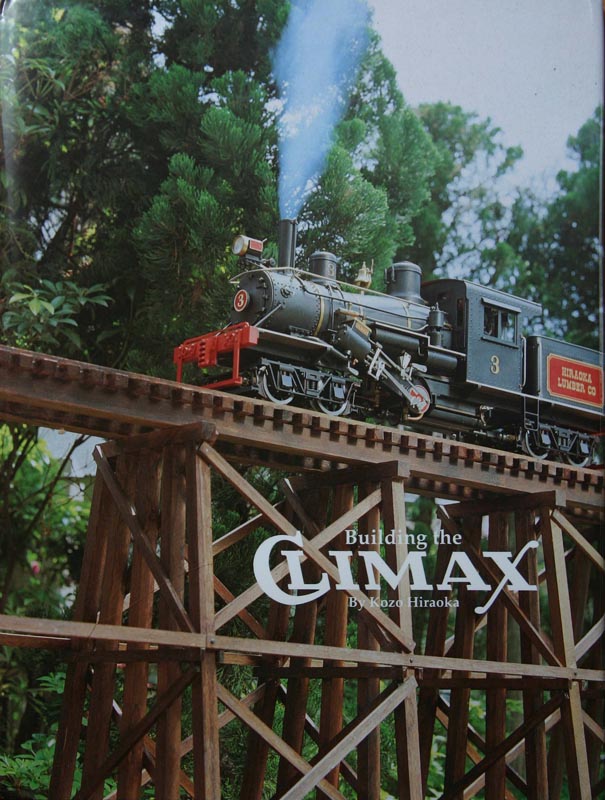

Another geared locomotive, the Climax (also pictured below), required five pairs of skew bevel gears. On these gears, the centerlines were offset from each other in a fashion similar to the hypoid gears used in current automobile driving mechanisms. Initially, it seemed impossible for an amateur to machine this type of gear. However, through several years of study Kozo succeeded in developing the calculation formulas.

He based this on the, “theory of uniform height tooth bevel gears on a hyperboloid,” by which industrially true gear teeth can be machined with simple tools by amateurs. Kozo’s instructions included how to calculate the dimensions of the gears and tools, and how to machine and heat-treat the cutting tools. He also wrote about how to machine the gears with a homemade index head on the lathe. Because the tooth profiles were logical in terms of mechanical geometry, the machined skew bevel gears ran smoothly, with an excellent tooth face contact pattern. No filing was required for adjustment. As far as the skew bevel gears were concerned, the working model of the Climax locomotive was equipped with those designed through a more advanced engineering practice than the original prototype!

Writing Instructions for Fellow Modelers

In addition to building the working models, Kozo enjoyed designing, photographing, making drawings, and writing instructions for them as packages. Compiling the instructions was a pleasurable way for him to share the joy of model engineering with others. Kozo’s first book, Building the Shay, was published in 1977 by Village Press, Inc. This was followed by the sister books, Building the Heisler, and Building the Climax. Each book covers instructions for all the components of each engine. These books have been a great resource for eager model engineers, including some of our own featured craftsmen, like Chris Rueby.

Some live steamers might be pleased with the instructions for fabricating a one-inch pressure gauge with a deadweight tester for calibration. Others could be excited by the theory and calculation formulas for the skew bevel gears in the Climax book. The designs and techniques presented in these books have been verified in professional ways—like strength calculation and fluid dynamics.

Learning English Adds Another Challenge

On top of all of the aforementioned tasks, in order to publish his instructions through Live Steam magazine, Kozo also had to teach himself how to write in English. Though he had been familiar with technical specifications in his business, the books for live steamers required something different. They needed to keep arousing the readers’ interest throughout the text.

After several trials, Kozo found that the most efficient practice was to make a comparison table, showing his original sentences next to those rewritten by the publishing editor. After receiving each issue of the magazine, Kozo would make a table, and then learn by comparing every sentence.

Besides the text, the most efficient tool for transferring an idea to the readers was through drawing—an international language, so to speak. The instructions were shown with dimetric drawings (a kind of 3D drawing) for easy understanding. Kozo drafted and inked all the drawings using pencil and rOtring pens.

Though he is familiar with CAD through his professional career, it has not been used in Kozo’s hobby drawings. This is because he thinks that high-quality handmade drawings are warm, and more attractive for readers.

After completing his three books on building the geared locomotives, Kozo’s next project was an instructional book for beginners. His work for this book started with selecting a prototype to model. After an extensive survey, the Pennsylvania A3 Switcher was chosen for the best balance between fabrication and performance.

The book contains instructions for building the engine, along with a guide for selecting and using every tool. By following the illustrated instructions a beginner can learn the techniques for, and enjoy the great pleasure of, building the working model from scratch.

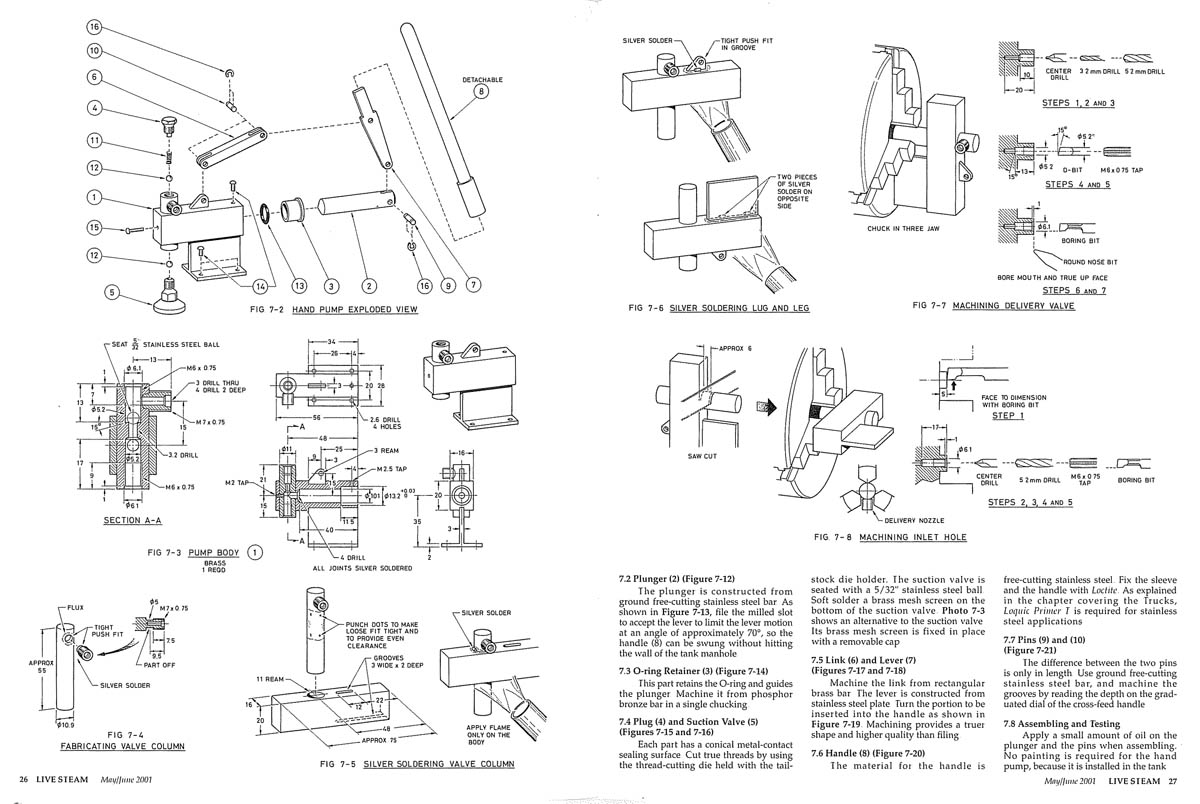

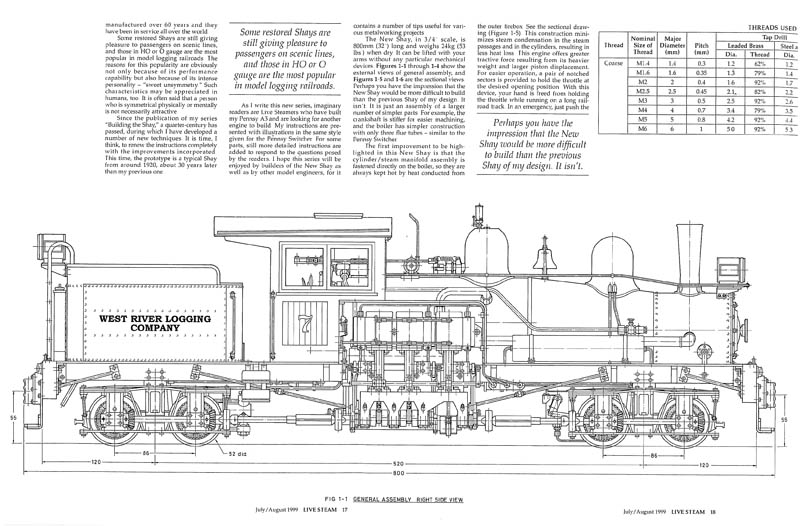

At the time of this writing, Kozo was working on a construction series for the “New Shay,” which ran in Live Steam magazine in 2004 (plans pictured below). This series contains the results of almost all of Kozo’s achievements in making difficult tasks look easy. The book, Building the New Shay, was published in April, 2007. It is Mr. Hiraoka’s latest publication.

To beginners, Kozo always says, “Think, and find a sure and easy way. The pro does his job in a way by which even the novice can do it—while the novice tries to do it in a way by which even the pro fails.”

Lifetime Achievement Award

The Joe Martin Foundation is proud to present the 2005 Lifetime Achievement Award to Kozo Hiraoka, for his contributions to model engineering through his books on small live steam locomotives. His excellent illustrations, clear photos, and concise technical writing have helped many people enjoy the pleasure of building their own live steam locomotives. Mr. Hiraoka was presented with an award plaque and an engraved medallion in March, 2005, in recognition of his many years of work in this field.

Books by Kozo Hiraoka

The following books by Kozo Hiraoka are still available for purchase through Village Press, and other retailers.

Kozo’s first book, Building the Shay.

Kozo’s second book, Building the Heisler.

Kozo’s third book, Building the Climax.

Kozo’s fourth book, The Pennsylvania A3 Switcher.

Kozo’s fifth book, Building the New Shay.

Kozo’s latest book, Building the Rio Grande Vol. 1.

Kozo’s latest book, Building the Rio Grande Vol. 2.