Scale World War I Aircraft With All the Right Details

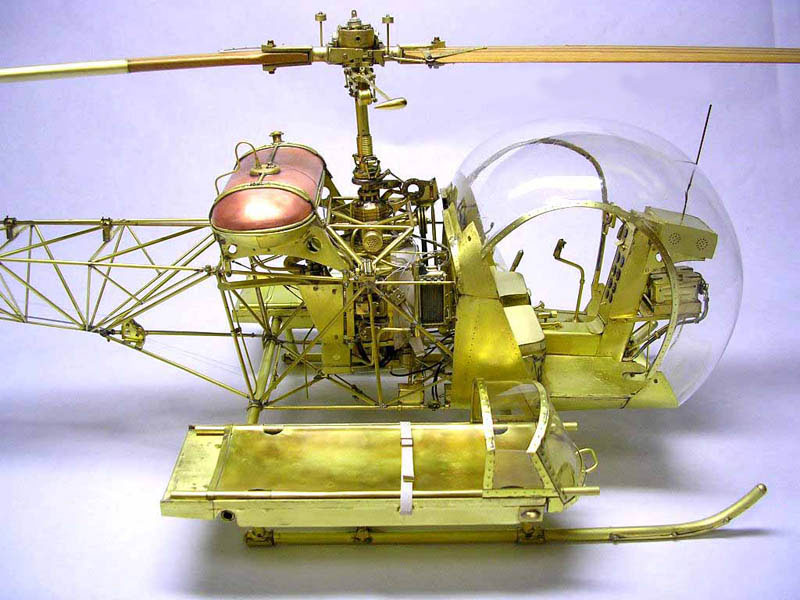

Ken Foran with a more recent project, a Bell helicopter that he made by special request for Fine Art Models. They would use the model as a master pattern for a limited edition run. Ken’s usual subject matter is aircraft from WWI.

Introduction

Ken Foran was born in Marathon, Ontario, Canada, and immigrated to the United States in 1965. He enlisted in the Marine Corps so he could get the GI Bill to attend college. After completing his three-year enlistment, from 1965-1968, with a 13-month tour in Vietnam, Ken attended the Cleveland Institute of Art. He graduated with a B.F.A. in Industrial Design. Ken spent his entire working career in product development. In that role, Ken and his development teams were given many patent and design awards, both domestically and internationally. Ken was responsible for the product development model shop, which utilized state-of-the-art prototype technology, including: 3D CAD, CNC machining, stereolithography, and hand fabrication.

Early Exposure to Model Building

Now, Ken’s first exposure to model building was watching his grandfather hand carve ship models while he was a child. His grandfather had immigrated to Canada from Denmark at the age of 16, and was a Canadian Merchant Marine for many years. He was “volunteered” into the Canadian Navy at the outbreak of WWII. After that, Ken’s grandfather then served on a Canadian Corvette, as a Chief Mate, in the North Atlantic convoys to Murmansk, Russia.

As a young boy, Ken would watch with fascination while his grandfather carved tiny ship models that he would then erect inside bottles. Ken still has one that his grandfather gave him. His grandfather also scratch-built large clipper ships, some of which ended up in local museums upon his death.

The first model that Ken built was a plastic Viking ship. It was given to him as a Christmas present from his grandfather when he was 10. Ken’s grandfather told him to always remember his “Viking“ heritage. Perhaps it was this heritage that lead Ken to join the Marine Corps.

Throughout his youth, Ken built various plastic and wooden models of airplanes, cars, ships, and even knights in armor. Early on, Ken would always go beyond the normal kit, doing what has now been coined as “kitbashing.” Ken had to take a hiatus from model building while in the Marine Corps; however, once in college his building skills really developed.

Military Experience Helps Pave the Way for College Achievement

Ken spent a lot of time in college building prototype models of products he designed. In college, not only did he have to design the product, but he also had to do the preliminary engineering drawings, and then build the prototype models using whatever techniques worked best. While in college, Ken was also selected to join the four-man group for the 1970 Clean Air Car Team at the Cleveland Institute of Art. Ken was the only underclassman on the team, and was selected because of his model building skills.

Those skills were used to fabricate a fully functional prototype car in six months, which was then tested at the GM proving grounds in Milford, Michigan. The car was awarded the Best Design Award. Ken’s background and education in the Marines are what really came into play in building the car. He had been trained as a Helicopter Structural Mechanic, so he just transferred his skills from helicopters to a car build.

A Return to Model Building

While Ken’s working career was very demanding of time, and he also traveled extensively around the world, he still managed to work with both of his children, Eric and Heather, on various school projects that required building. His son Eric figured out early on that he preferred flying RC planes to building them. Ken was a better builder than a flyer, so they made a great team.

Ken was always interested in how things were built, rather than how they looked finished. To this end, Ken started scratch-building models after years of assembling kits, and being somewhat disappointed in their quality and depth of detail. His first early attempts were WWI aircraft. Ken wanted to build certain aircraft that were not available in kits. Having built a few of the Guillow’s kits that were commercially available, he realized that the 1/16 scale was a good size for both detailing and display.

For modelers, especially married ones, storage and display is always an issue. For some reason, wives do not see the real decorative value of models around the house. Over the years, Ken has accumulated an extensive collection of tools that includes a tabletop lathe, drill press, milling machine, and hand tools. Most of these were found at liquidation sales of one form or another. Ken admitted to not being a machinist, and is self-taught on the equipment. Having the right tool for the job is the key to great model making. A lesson taught to him by his father was, “Sometimes the biggest mistake you can make is to buy cheap tools.”

Ken also taught himself how to use computers over the years. He admitted that as a corporate executive, he paid for designers and engineers to be trained on 3D CAD programs, but Ken himself was never in the position to learn the programs.

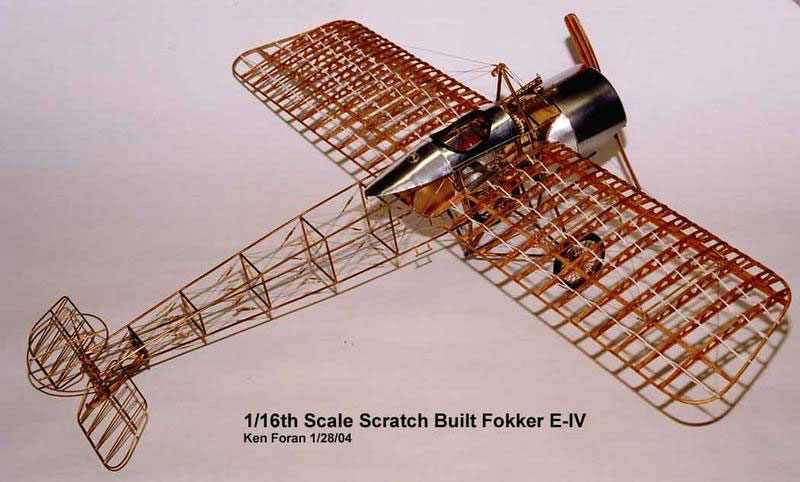

Ken Foran (right) explains some of the details of his Fokker Eindecker E-IV to a spectator at the 2008 NAMES Expo in Toledo, OH. In the foreground is his 1/16 scale Fokker D-VII. Being only a few hours drive away, Ken was kind enough to bring over two of his models for display at the Joe Martin Foundation booth. Ken’s models were greatly appreciated by the many craftsman who attended.

Getting Started With Scratch-Building

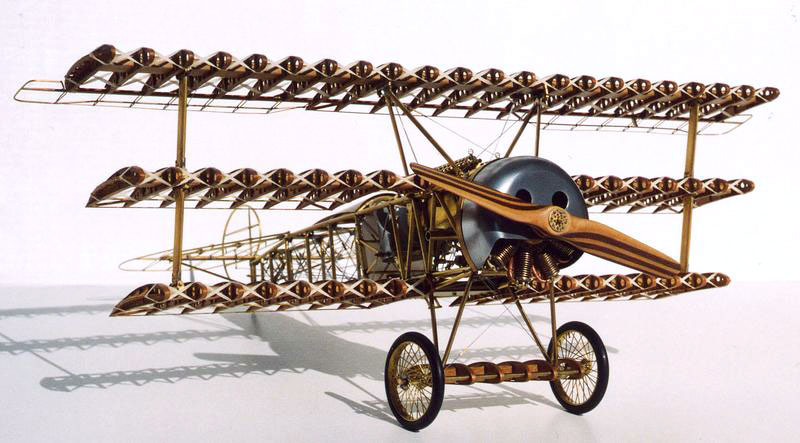

Ken has had a lifelong interest in airplanes, especially the WWI era planes. He attends all of the Dawn Patrol fly-ins at the Wright–Patterson Air Force Base, held bi-annually. As mentioned earlier, Ken was disappointed with the level of detail on commercially available kits. So rather than complain about that, he decided to take matters into his own hands, and started scratch-building his own. His first attempt was the Fokker Triplane.

Ken does all of his own research, and scours the internet looking for resources, reference material, and images of the planes to build. He noted that he’s very careful about using the drawings of others, because he’s found errors or outright mistakes in some. Ken said, “Whenever possible, I try to obtain original drawings or pictures from the period, and yes, there are sources out there to obtain them.” Eventually, Ken built the triplane, which he said was his first attempt and a learning experience.

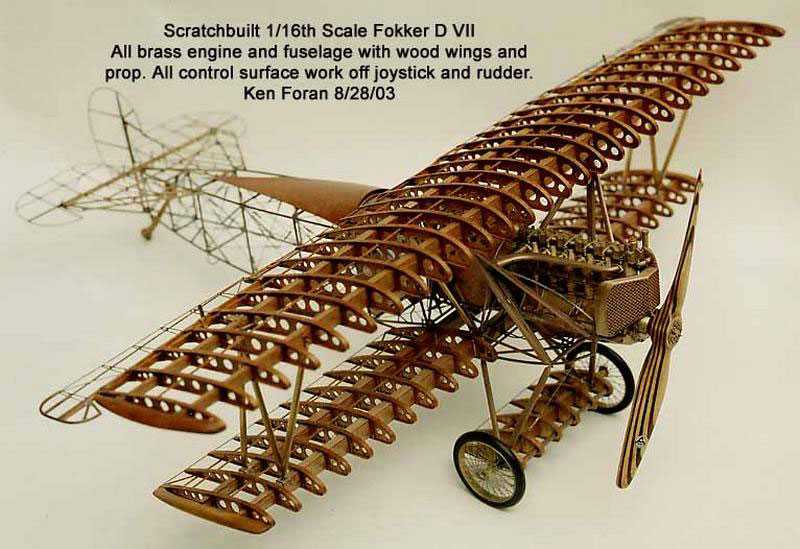

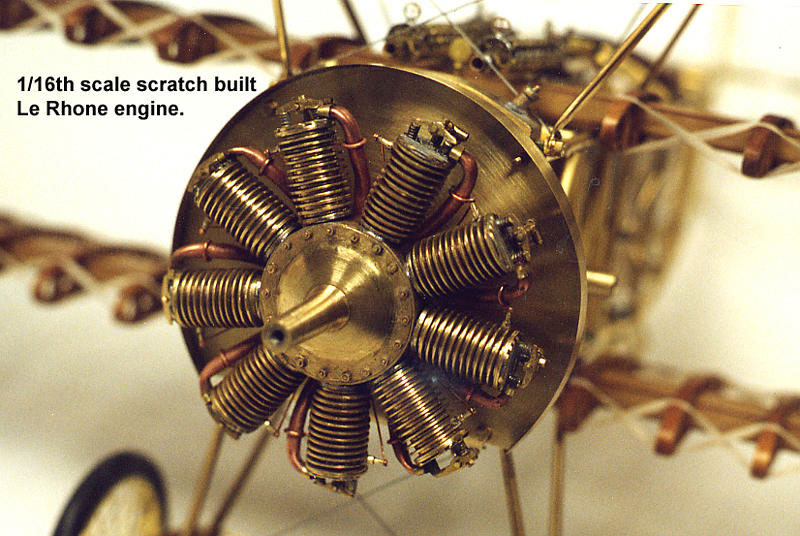

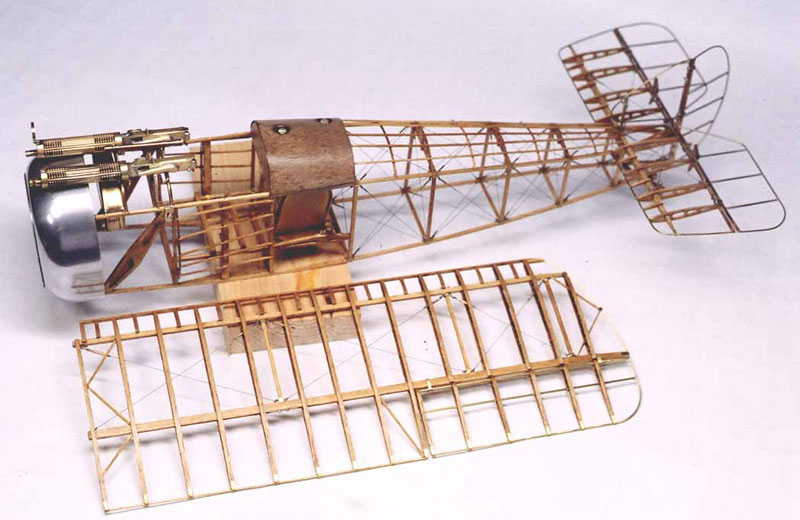

Then, his second project was the Fokker D-VII. He selected this plane because of the engine, and also because he wanted to push and develop his brass working skills. Again, Ken taught himself how to solder, work with, and fabricate brass. He felt that brass was by far the fastest and easiest medium to work and construct with. Ken noted that, “Many times I can build component parts while they are still hot from soldering, not having to wait for glue to set.”

Additionally, just about any shape, size, profile configuration, or sheet thickness is available in brass—and all can be soldered to each other. The Fokker engine did, in fact, challenge Ken’s building skills. He hand-fabricated and shaped the upper and lower crankcases with files. Ken said he had to work very slowly and carefully, for there was no chance of using filler if a mistake was made.

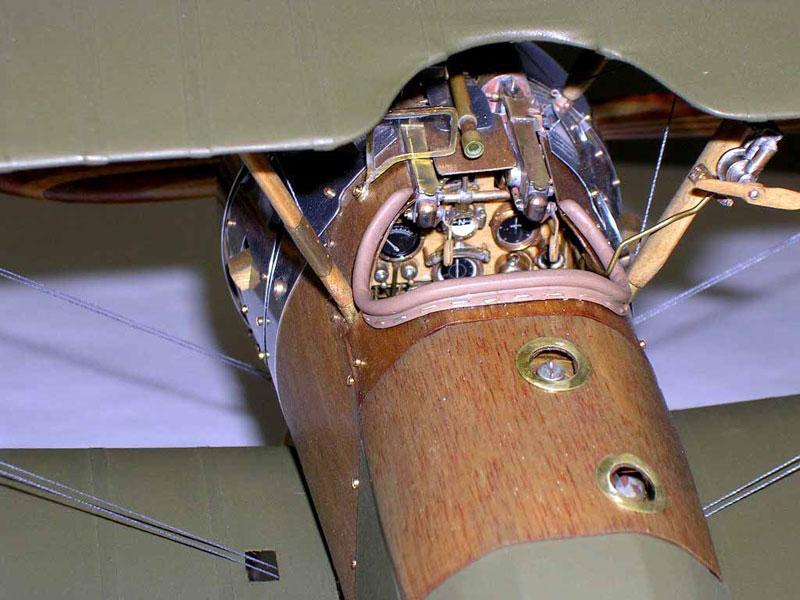

Now, all of Ken’s planes are built as close as humanly possible to replicate the real thing. All control surfaces work as they should, off the joystick and rudder bar. Some of Ken’s planes even have working suspension. Ken’s wife, Gretchen, helps him by hammering the cowls using .020″ dead soft aluminum. Gretchen is also a graduate of the Cleveland Institute of Art in silversmithing, and taught there for ten years. Ken says it’s amazing to watch her take a small circle of flat aluminum, and with nothing more than hammers and stakes, hammer cowls that are not only round, but also to a press fit tolerance.

Eventually, Ken posted images of his two Fokkers on a popular WWI website. Almost immediately, he started receiving accolades from around the world, which totally amazed him. Ken would receive requests on how to do this and that with modeling. He noted that he’d even emailed a renowned modeler with step-by-step instructions on the silver soldering process. Ken said that the modeling community is a great group of people, and that he enjoys sharing knowledge and building tips with others.

The aluminum cowl on this Sopwith Camel was expertly shaped by Ken’s wife, Gretchen, an experienced silversmith.

Notoriety Brings New Challenges

Before long, Ken had started his next project—a Fokker Eindecker E-IV—to round out the Fokker series. He had also started an obscure model, with a double bank rotary engine, when he learned that someone had sent a link of his work to Gary Kohs, of Fine Art Models. Ken and Gary emailed back and forth, with Gary wondering if the Fokker Triplane was in fact one of Ken’s models.

Ken was not aware of Fine Art Models at the time, and after a few emails Gary invited Ken to visit him in Detroit. Gary wanted to see the planes and Ken’s work in person. Ken had also brought the E-IV, which only had the engine, fuselage, and tailplane complete.

Within 5 minutes of looking at the models, Gary invited Ken to attend the Nuremberg Toy Fair, and to build a Sopwith Camel for Fine Art Models. Upon the completion of the Sopwith Camel in 1/15 scale, and exceeding Gary’s expectation with the build, Gary then offered Ken a challenge.

Gary told Ken that he had always wanted to build a certain model, but that in the previous 13 years he had not been able to find a builder to do it. Much to Ken’s surprise, it was a Bell H-13D Sioux M.A.S.H. Helicopter. Of course, with Ken’s background as a helicopter mechanic in the Marines, this was right up his alley. So Ken accepted the challenge, and located an H-13D being restored in Canada.

Ken visited with the folks restoring the helicopter for two days, shooting 10 rolls of film, and making numerous sketches with dimensions. Later, he located an engine builder in Detroit who was rebuilding a Franklin engine—again, a visit where rolls of film were taken. Ken also located and purchased original parts catalogs and erection manuals, with more details and dimensions. Ken said that, “God is in the details.” He tries to be as accurate as possible when he builds, and noted that the better the information, the more accurate the model.

With regard to the M.A.S.H. helicopter, the challenge was that most of the components had to be fabricated out of brass. The model is not only a prototype—it would also be used to make master patterns and molds for casting in brass. Thus, the model would have to be able to be disassembled and reassembled. To add features, Ken also enabled the main rotor to turn the tail rotor, and to turn the cooling fan for the engine. Note the 1/8” diameter working universal joint. He indicated that the greatest challenge was that there was little margin for error, because everything is seen.

Ken also noted the wide variety of component configurations and changes, which evolved over the years with model changes and upgrades. Fine Art Models have exhibited the H-13D model at the London Model Engineering Show, and the International Toy Fair in Nuremberg, Germany in 2006.

Additionally, Ken has sent us a number of photos of his planes and projects.