Beautiful Finishes on Unusual Projects in Wood and Metal

An Early Introduction to Woodworking

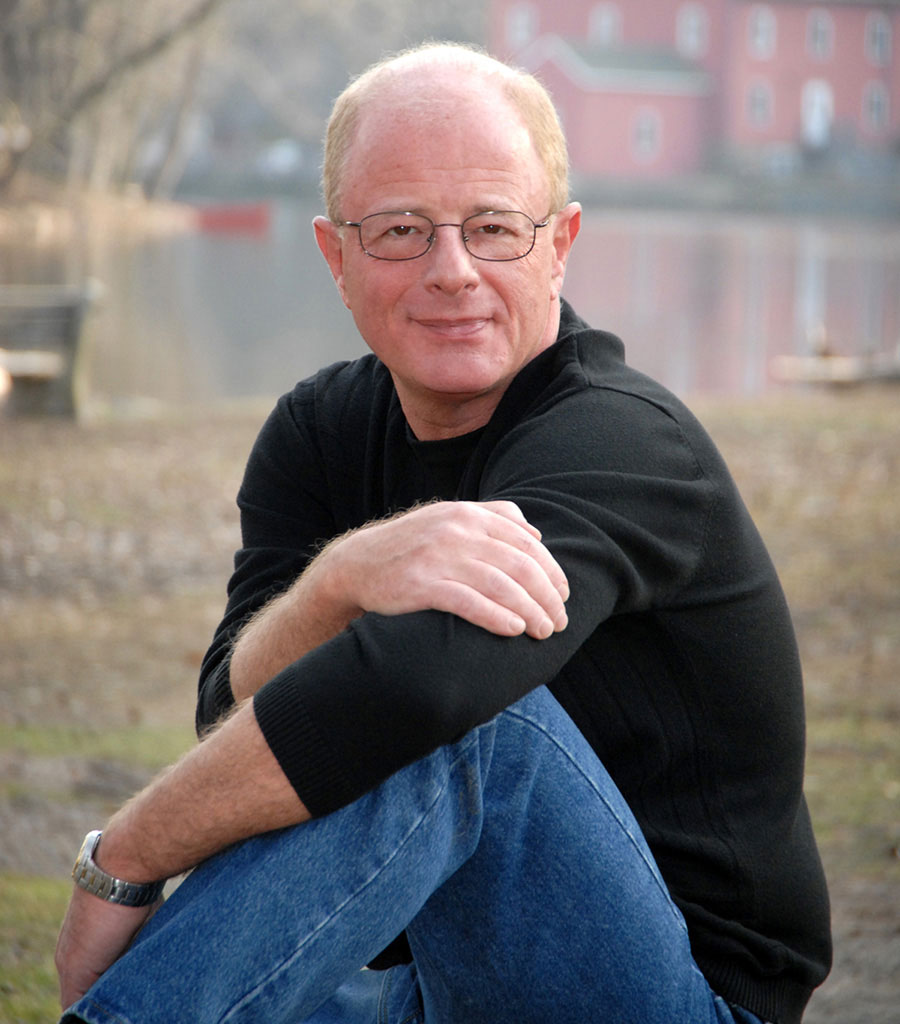

Ken Condal was first introduced to woodworking at the age of seven. While converting the basement into a playroom for Ken and his brothers, Ken’s dad taught him to use basic hand tools. He still remembers the fascination of watching raw lumber being turned into walls and built-in cabinets. While growing up, Ken used those skills to build forts, tree houses, go carts, and even a pair of stilts. A high school shop class introduced him to power tools, and much more refined techniques.

From Chemistry to Computers

Ultimately, woodworking was mainly a hobby for Ken. He studied chemistry in college, but it wasn’t the career he was looking for. At the time, computers were in their infancy with paper tape and punched cards. Much like woodworking, Ken soon realized that those simple things could be turned into complex programs that solved real world problems. Ken switched careers, and his first job was mounting tapes in a large computer room. A year later he was programming.

Now, there wasn’t much down time in the computer field, but Ken made the time. He became addicted to This Old House, The New Yankee Workshop, and other shows of that type—learning more advanced skills. There was no internet at the time, but there were lots of woodworking magazines, and Ken read them all.

A custom wooden knife block made by Ken. As his woodworking skills improved, his projects got more ambitious, and the finishes were perfected.

From Simple to Advanced Furniture Making

It wasn’t long before Ken got back into woodworking with his own furniture. First came simple pine furniture, stained and coated in varnish. Friends would ask, “Did you make that?” Although it was always meant as a compliment, Ken never took it that way, constantly thinking “I’ve got to do better.”

As the years passed, Ken acquired more skills, more tools, and enough money to start using exotic hardwoods. No more stain and varnish—now it was hand-rubbed oil finishes. Instead of being asked, “Did you make that?” Ken was being asked, “Where did you buy that?”

Another wooden table crafted by Ken. His pieces are so well made that he’s often asked where he bought them.

Combining Woodworking, Music, and Computer Programming

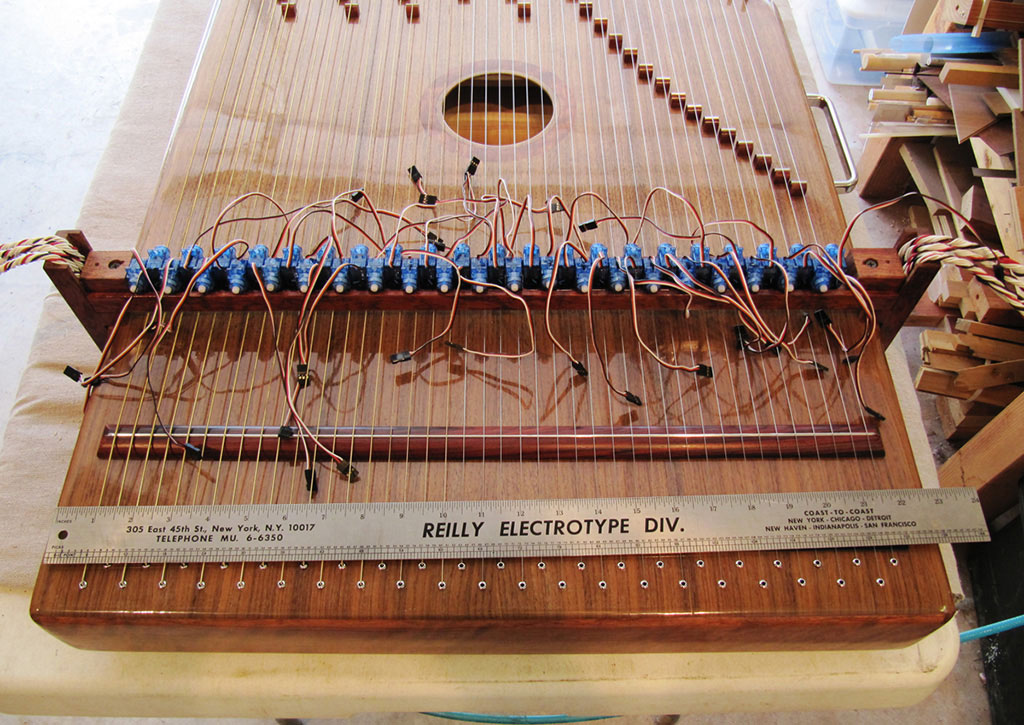

Now, having reached his goals with furniture, Ken decided to try something crazy—building a self-playing acoustic guitar. This would combine his love of woodworking, music, and computer programming. The end result doesn’t quite look like a traditional guitar, but it sounds like one.

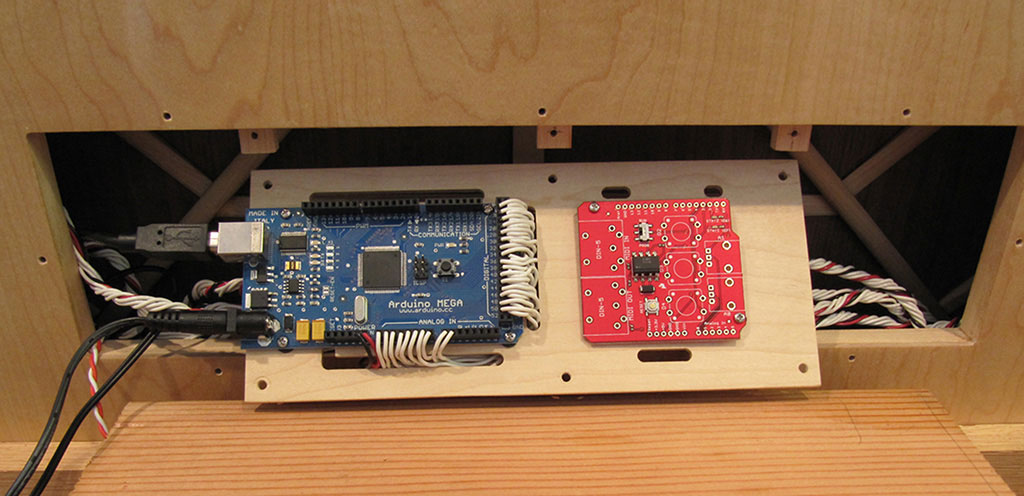

Rather than having a mechanism to fret the strings, Ken pre-fretted them, creating an instrument with 42 strings. Each string could be plucked by a servo, receiving its instructions from an onboard Arduino.

In turn, the Arduino receives notes via a MIDI stream from a laptop. Ken thought he could make the pluckers (odd shaped servo arms with picks attached) using a router table and a template; however, that proved to be both difficult and dangerous due to their small size.

Ken had seen videos of CNC machines, but didn’t know much about them. Some online research led him to the Sherline site, where Ken found a package containing a desktop mill, lathe, and computer.

Ken’s finished MIDI guitar has 42 strings. This project involved woodworking, electronics and music.

Ken joined a Yahoo group devoted to Sherline CNC users and asked a bunch of questions, which were promptly and courteously answered. He then spent several weeks watching YouTube videos of people making amazing things, though mostly in metal. He was hooked! Ken had always been fascinated by museum pieces made in metal, so he figured the tools could be used to finish the guitar, and then he would graduate to metal working.

Eventually, Ken decided to buy the Sherline package. He spent a few days setting it up and learning the very basics—like moving an axis. Now what? Proceeding any further would require a CAD/CAM package, and learning how to use it. Then came material and tool selection, feeds and speeds, fixturing and so on. Almost a year went by, and Ken learned the ins and outs of CNC machining while also accumulating quite the scrap pile.

Now it was time to take the guitar out of storage and complete it, which Ken did. However, as all of this was happening, Ken realized that his small shop couldn’t accommodate the delicate Sherline machines and their computer. There was always a constant cloud of sawdust from the large woodworking tools, which was a problem.

Sadly, Ken made the decision to give away all of his woodworking equipment. Fortunately, he was able to find a young man who had the same passion for woodworking that he did at that age. Moving forward, all of Ken’s projects would be metal.

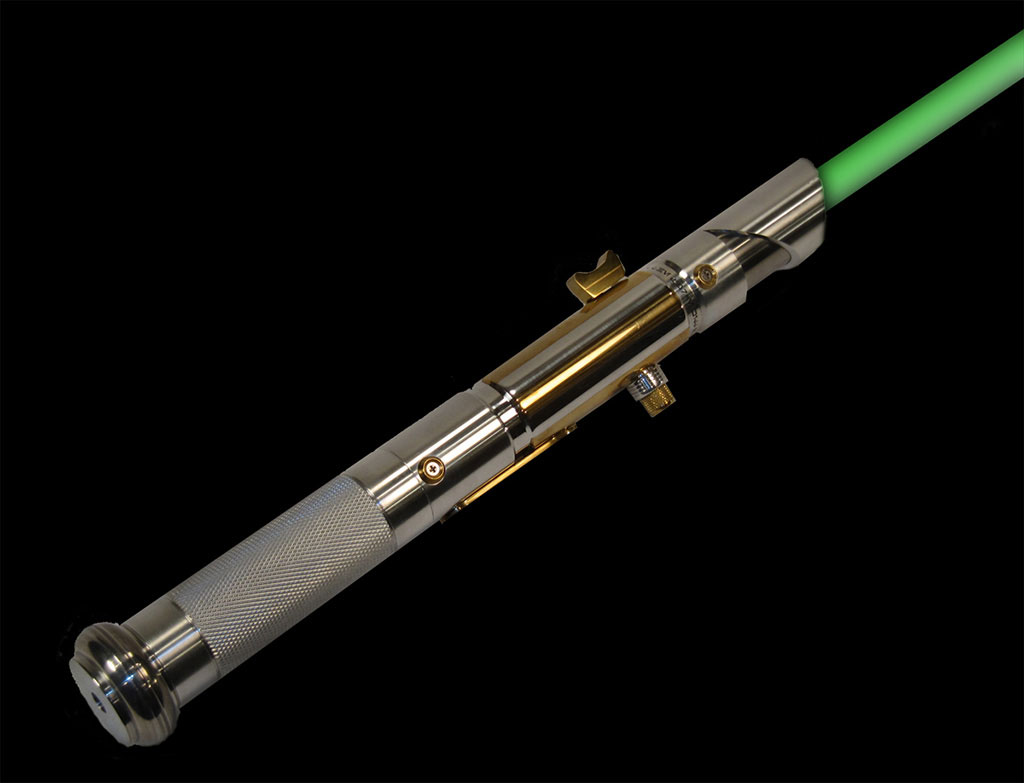

From Wood to Metal—Making a Jedi Lightsaber

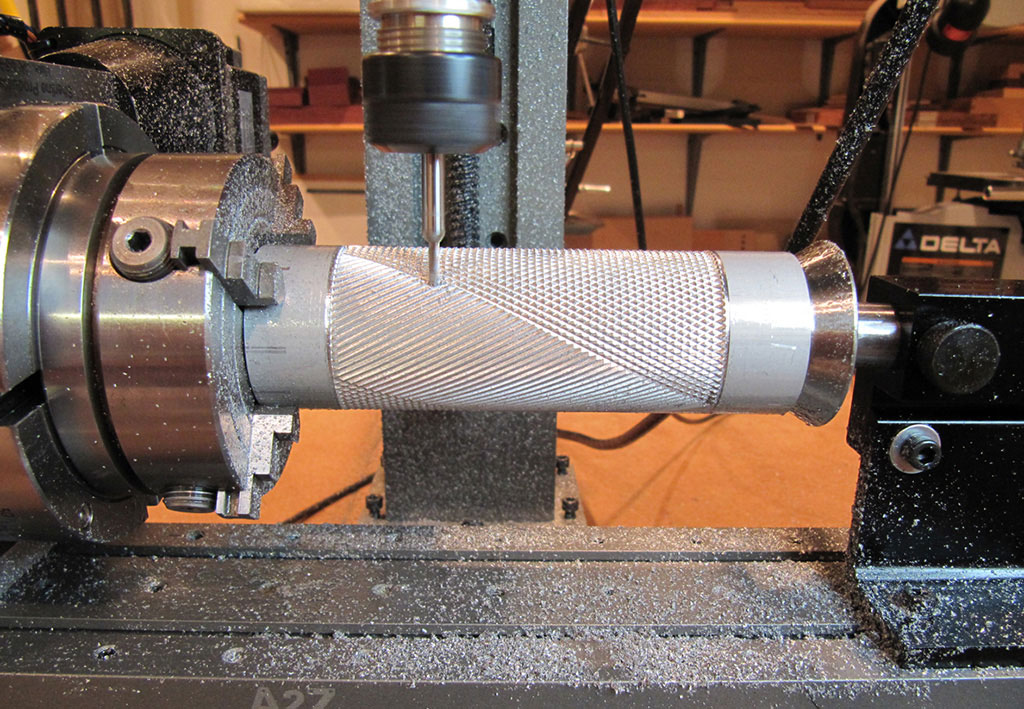

First up was a lightsaber, because every Jedi needs to make their own lightsaber. Ken had no idea what he was getting into for a first project, but he soon found out. Turning and milling was to be expected, but internal and external threading—along with fourth axis knurling—was a lot to learn.

At first, the plan was to just make the hilt, but Ken found a small piece of electronic wizardry that inspired him to keep going. The electronic component could light a straight neon tube from near to far end, all controllable with a variable resistor.

Once the decision was made to use this, Ken’s design began to take shape. All he had to do was figure out how to cram the electronics, two 9-volt batteries, a variable resistor slide switch, and an on/off switch into the hilt.

Ken spent a lot of time searching for stock aluminum tubes with the right dimensions. They needed to be machined and mated with internal and external threads, but still have enough interior room for the electronics and batteries.

What Star Wars fan wouldn’t want one of these? Ken decided to get into making metal parts, and was looking for a simple first project. However, his finished lightsaber was crafted too well to be considered amateur work.

Since this was Ken’s first metal project, a lot of trial and error pieces ended up in the scrap bin. When he decided to inlay brass into the aluminum hilt (because woodworkers love inlays), things got even more problematic. But Ken wasn’t done complicating his first project. He had found a Jedi font online, and wanted to engrave, “The force will be with you. Always.” around the cylindrical hilt. How hard could fourth axis engraving be?

The project took nearly a year, but all the techniques that Ken learned along the way would prove useful for future builds. Plus, the lightsaber is a real conversation starter when friends see it for the first time. Ken built a stand to display the lightsaber using black Corian and clear acrylic, two materials he would use frequently in future projects.

Around the handle of the lightsaber, Ken engraved the Jedi script: “The force will be with you. Always.”

A Movie Inspires Ken’s Next Project

The next idea came from Ken’s son, who gave him a working replica of the cryptex from the movie, The Da Vinci Code. The cryptex had a simple note attached, “To inspire your next project.” Naturally, Ken soon had the cryptex in pieces to examine its inner workings.

A cryptex consists of nested cylinders with an outer ring of letter dials. Only when the dials are turned to spell a specific word will the cryptex open to reveal its secret contents. Internally, a cryptex is similar to a key turning the cylinders in a lock.

The difference is that the key remains stationary inside the cryptex, and the cylinders (with letters on them) are turned until they align with the key. The internal mechanism required some very precise machining, which Ken says he really wasn’t prepared for.

The outside, on the other hand, was fun to make. Once again, Ken had to do some fourth axis engraving for the letters. The inlays, used to mark the selected letter, were made of wenge hardwood.

Inspired by the movie The Da Vinci Code, Ken’s cryptex device is used to conceal and lock documents (in this case, a USB drive). A series of rings and tumblers must be placed in the proper position for it to be opened.

Gearing Up for an Advanced Project—Building an Orrery

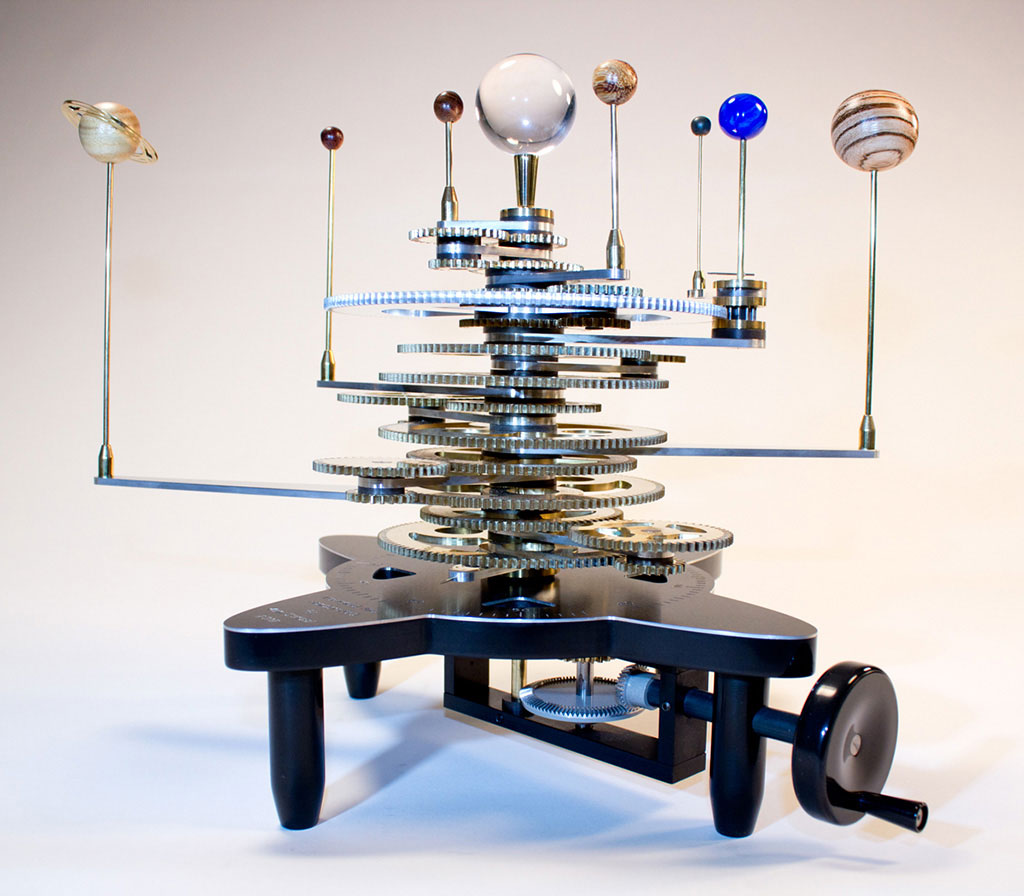

Ken was now feeling more confident in his abilities with these new machines, and wanted to build something more inspiring than a movie prop. He had read an article in Digital Machinist, describing the build of a simple orrery involving only the earth, moon and sun.

That article reawakened Ken’s memories of some beautiful orreries he had seen in museums, movies, and online. Ken knew nothing about working with gears, or even how to make one, but was determined to learn.

Ken found a software package called Gearotic Motion and began playing with it. Over the next three months, he read everything he could find about gears, and the motion of the planets around the sun.

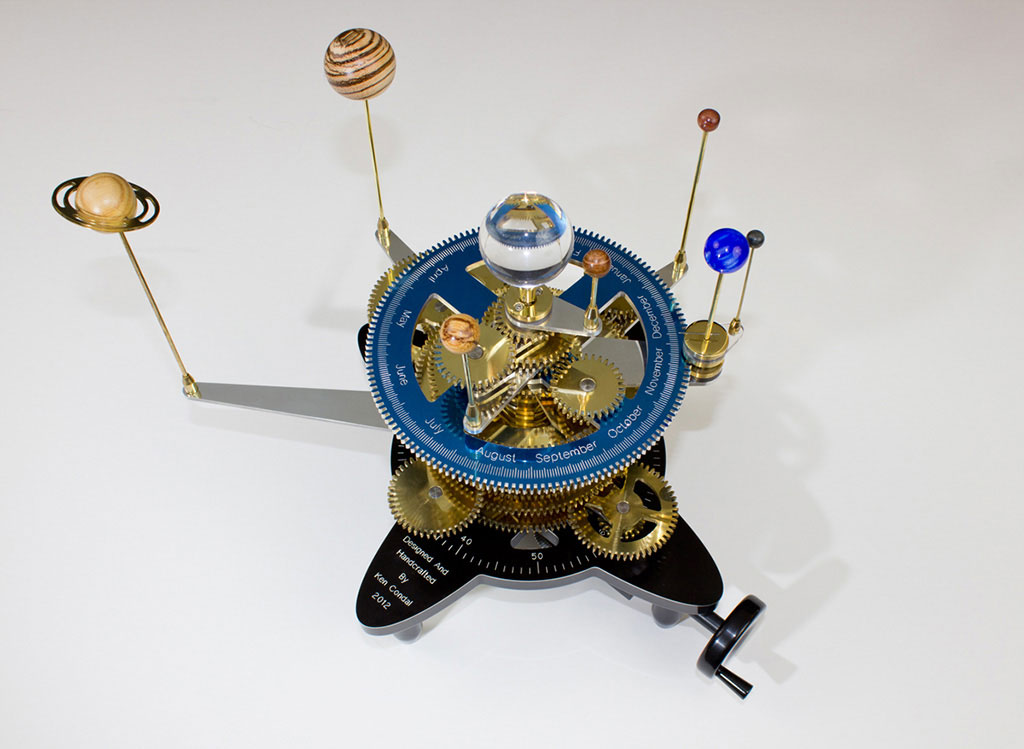

Then, Ken built a spreadsheet that let him experiment with different gear ratios. Eventually, he found a combination that would drive the moon, along with the planets from Mercury to Saturn, in near perfect proportion to their actual orbital periods around the sun.

Ken posted his preliminary plans for the orrery on the Sherline CNC Yahoo group, and began asking questions about assembling the mechanism. He wanted to know how the pieces would fit together, and how the planet arms could be made adjustable. If they were adjustable, the orrery could be set for a particular date, longitude, and latitude.

David Clarke, a member of the group and former NASA machinist, jumped at the chance to help out. David came up with a design involving clutches that solved the problem. He also took the time to instruct Ken on proper gear making techniques.

Documenting the Process

Ken wanted to document the build, and also to give back to the YouTube community that had been so helpful in teaching him many techniques thus far. From the first step of his orrery build to the last, Ken filmed and narrated each process, editing and uploading them as he proceeded. After finishing the project, Ken realized that he had posted nearly five hours of videos.

Now, only the most dedicated people would watch that, so he made a time-lapse of the build titled, Orrery Construction Time Lapse – Seven Months in Seven Minutes. The time-lapse video, which can be viewed below, proved to be Ken’s most popular post and attracted many would-be machinists.

Building Stirling Engines

Ken’s next two projects involved Stirling engines, which he knew nothing about—except that they looked cool. More research led him to Jan Ridders of the Netherlands, who designs and builds a wide variety of these engines. Jan has publicly provided beautiful plan drawings and detailed explanations of how the engines work.

Now, Ken chose a model that used magnets instead of a mechanical linkage for the return stroke, because it added a bit of mystery to the process. Holding the tight tolerances between piston and cylinder was a challenge, but after a few tries he had it right. The next trick was to figure out how to cut Pyrex test tubes on a lathe.

Ken used a Dremel tool outfitted with a diamond cutting wheel, and mounted it to the cross slide to get the desired result. Although, many test tubes were sacrificed in the learning process. Despite his best efforts, when the engine was completed it didn’t work.

After trying everything he could think of, Ken contacted Jan and asked for help. Jan was kind enough to spend hours helping him determine what was wrong, and eventually the engine was running. Ken noted that this willingness by total strangers to work together, even when they’re separated by an ocean, is one of the most enjoyable aspects of the hobby.

Ken’s polished Stirling engine. It features a clear glass displacer and main cylinders, so the piston action can be seen.

Now that Ken had a better understanding of how Stirling engines worked, he tracked down plans for a helicopter that several others had built. The design was both aesthetically and functionally magnificent, so Ken dug in and got to work. Much of the build involved techniques that he had learned on previous projects, so for once things proceeded smoothly.

The trickiest part was the 3D contouring of the rotor blades. Ken’s CAM software supported this, but it wasn’t straightforward. It required a lot of guesswork regarding step over, cutting depth, and the like. This took several tries, but the parts came out beautifully in the end. Watch a YouTube video below of Ken’s Stirling helicopter.

This project adapts the workings of a Stirling engine into the form of a brass helicopter, so observers can see more than just a piston moving.

At the time of this writing, in 2015, Ken was looking for inspiration to determine his next venture. Having successfully completed several very different projects, it’s anyone’s guess what this talented craftsman will do next.

View more photos of Ken Condal’s unique projects.