Exploring the Beauty of Craftsmanship—Turning Metal Into Art

Introduction

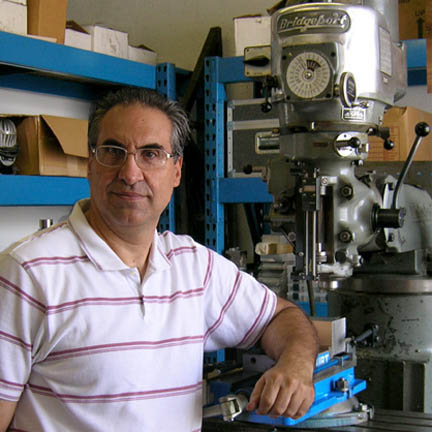

Machining is often seen as simply a way to get from a block of raw material to some useful part. However, among those who shape metal—either for a living or for the love of the process—the machined surfaces, shapes, and resulting constructions often have a beauty of their own that transcends function. In his youth, John Gargano discovered that there is both beauty and permanence in working with metal. After a career in architecture, he returned to what he really loved—creating works of art in metal. Fellow metal workers reading John’s biography will likely find much in common with his experience.

In John’s biography, he has managed to convey how and why he worked as he did. We have included a few photos of his main pieces so you can see how his life experience has shaped his work. John’s pieces are unique, and there are no schools for this kind of work. It comes from the hands, the mind, and the heart.

Early Experiences Building Models

John Gargano grew up in New Jersey. From his early childhood days, he recalls being fascinated with making things. He made all types of plastic models of cars, boats, planes, and military vehicles. He built train sets, and many kinds of wooden models. John played with Lincoln Logs, and also had an Erector set and a chemistry set. He made numerous science projects. One year, he made a scale model of a Mercury capsule, complete with the launch escape tower that was over four feet tall—all from scratch.

Growing up, John continually had some type of wheeled vehicle in some state of completion. Throughout his school days, John remembered always carrying around a wood shop project, along with his books and gym bag. John found hobby shops to be an endless source of inspiration. He never tired of looking at the various materials and processes that people were employing to create their projects.

With regard to building, John loved working with plastic, spray paint, colored pencils, balsa wood, decals, Testors cement, and X-Acto tools. When he wasn’t making something of his own, he was working with his father who was a home builder.

One summer, John, along with his brother and cousin, began cutting out circles from old sheets and attaching eight to ten strings to the perimeter. Then they experimented with tying rocks and other heavy objects to the strings, trying to form homemade small scale parachutes. They rolled these up in every conceivable way. The trio proceeded to hold contests where they threw the parachutes up in the air as high as they could, watching how slowly they could get them to come down. And they did this all summer long.

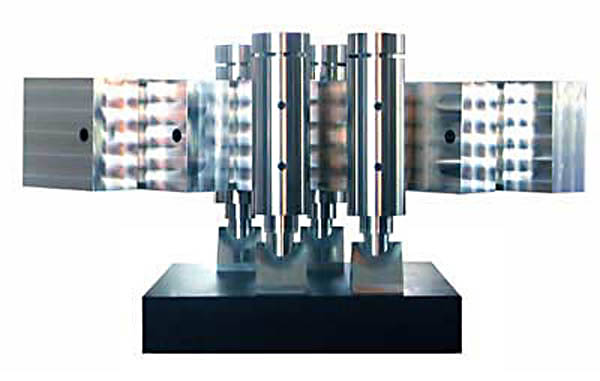

This sculpture entitled, “Dupree,” demonstrates the kind of shapes and finishes that John Gargano achieves in his work. John’s sculptures incorporate round elements made on the lathe, as well as flat and angled components that are machined on a mill. This sculpture is nickel plated aluminum, and 48” long x 19” wide x 48” high.

The Beginning of a Love Affair With Metal

After taking wood shop in school for many years, John finally opted to take a class in metal shop while in high school. He remembered his guidance counselor having an issue with taking metal shop once per day as a major course, as opposed to three times a week as a minor one. Since he was preparing to go to college, John was strongly discouraged from taking metal shop as a major. Nonetheless, he prevailed. He was fascinated by the power of the machinery, and liked the strength and permanence of metal objects, as opposed to those made of wood or plastic.

John recalled the enthusiasm of his metal shop instructor, who was a very dedicated, caring, and knowledgeable teacher. It seemed the capabilities of the metal shop were those of industry. No longer was John limited to making toys, scale models, or crude devices. In his first year, John learned about the capabilities of each of the machines, and the endless possibilities that could be achieved with fasteners, castings, welding, sheet metal, and machining.

In his second year, he took on a project that even his shop teacher tried to discourage—a ball-peen hammer from the South Bend project book—which had a tapered, knurled, and hollow handle. John went on to complete that project, much to the amazement of many people. It even won a prize in the annual science fair. The only problem with building the hammer was that John had to carry around the dirty, greasy bars wherever he went, for fear of having them stolen from a locker in the metal shop.

Aside from all of the knowledge he gained about materials, processes, and techniques, John had no idea that he was in the process of discovering something about craftsmanship that would transcend the face value of even the most skillfully made object. The metal shop came to represent an entire realm of capabilities, and John enjoyed working there so much that he even developed an affinity for that particular smell of a metal shop.

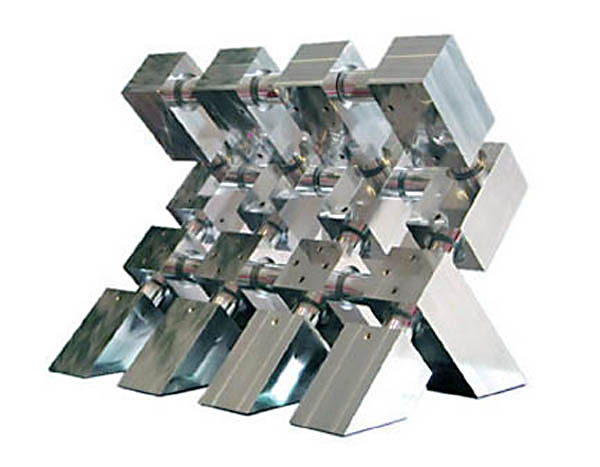

This sculpture is entitled, “Stiletto.” The piece is nickel plated steel, and 33” long x 13” wide x 11” high.

John later learned that by taking up the task of making tangible objects, he was accomplishing something that many people seemed to find illusive. After many years of making so many different things, John had no idea that by learning how to craft with metal, he was also developing a sense of confidence, and becoming a capable person. These things led to an overall feeling of confidence, and the development of a vivid and powerful imagination. These intangible attributes of character eventually came to permeate every aspect of John’s life.

When it was time to go to college, Mr. Gargano initially studied liberal arts. However, he quickly realized that this was not the most appropriate route for him. At that point, he transferred to Virginia Tech to study art and architecture. In his freshman orientation at Virginia Tech, John remembered a professor from Switzerland telling all of the new students, and their parents, that the college of architecture had no classes, no books, no lectures, and no tests. All they had were projects.

A hush came over the room, as everyone seemed to be amazed by this statement. Everything they had known about education up until that point was about to change, and they seemed visibly worried. John, on the other hand, was so elated that it took restraint to keep from jumping up and cheering! Over the next several years, he totally immersed himself in projects of all types. During those years, John had the feeling that sleeping was nearly a complete waste of time.

In John’s third year of study, he developed a five foot square modular graphic composition, which was made of illustration board and colored paper with a wooden frame. After the class in which he presented that project, the same professor from Switzerland who was at orientation three years earlier took John aside. The European professors at the time were not known for their diplomacy while evaluating the merits of a student’s work. To say there was a bit of tension in the moment would be an understatement.

The professor looked at Mr. Gargano very sternly, and said with a heavy German accent, “You should now begin to use more permanent media in your work.” Having prepared himself for a sound thrashing, John needed a moment to fully process the implications of that remark. Everyone at the time was making models and various design projects out of paper or cardboard, because with up to three projects per week, those materials were inexpensive and easy to work with.

Also, since the projects were only for learning about concepts, they had little value after completion, and were mostly discarded. With the recommendation to use more permanent media in his work, it took John no more than a few seconds to come upon a very simple yet distinct realization. He thought that going forward he could make his projects out of metal, and machine them if they were three dimensional.

The Seeds Are Planted for a Future Project

Despite John’s newfound realization, it was only shortly afterward that he came up against a stark reality—there was no machine shop! In high school, John’s machine shop had three South Bend tool room lathes, a pristine Bridgeport milling machine, a shaper, a drill press, two band saws, and many other tools for cutting and bending sheet metal. The shop also had a furnace and crucible for melting metal for casting, two welding machines, and supplies of materials, abrasives, and fasteners to be envied.

By contrast, the Virginia Tech College of Architecture, at that time, only had a rudimentary wood shop and several dark rooms for photography. Nevertheless, the distinct idea of machining the components of his work lingered in John’s mind for years. In the entire realm of artistic composition, one can readily see stone, plaster, cast bronze, clay, welded metal, glass, sheet metal, plastic, and nearly every other material and process known to humankind. However, after years of looking, John noticed that there was vanishingly little machining, or other industrial techniques, employed in the creation of artistic compositions.

There is no question that the most often used medium was paint on canvas. Why was this? John kept coming back to this seemingly obvious question. On every visit to nearly every museum, from New York to Washington D.C. (and that’s a lot of museums), John kept seeing similar media and techniques, over and over.

Mr. Gargano went on to practice architecture in Colorado for many years, and even took on simple industrial design projects. He kept up his photographic skills, and engaged in silk screening and painting. All along, though, that question from the third year of his college studies continued to linger in his mind. Why not use more permanent media? Why not make artistic compositions from machined elements?

Back To School After Twenty Years

Twenty years after graduating from Virginia Tech, after having practiced architecture and venturing into other diverse design disciplines, John decided that he had spent enough time thinking about this question. It was time to take on the task of learning the machining trade for the sole purpose of making artistic compositions.

So, John immediately enrolled in trade school, and began taking classes in downtown Denver three nights a week after work. It was clear that the trade school was on its last leg and about to be shut down. The machines were all very old, everything was out of square, and all the cutting tools were dull. Of the 14 students in the class, three were from Indonesia, two were from India, three were from China, and nobody knew about the last foreign student because no one spoke his language. All but three of the students were in the CNC class, and had never used manual machinery.

Again, Mr. Gargano had to persist against the strong encouragement to start with CNC. It was explained in the very first class that no one used manual machinery any more, and there was really no one to provide instruction for it. When John explained that he wanted to learn how to use the Bridgeport milling machine, he was told that he needed to learn how to use the lathe first. And the first thing someone had to do in learning to use the lathe was to grind a cutting tool—by hand on a dilapidated grinding wheel!

During the second class, John brought in the ball-peen hammer he had made in high school. He showed it to the teacher, hoping to persuade him that he could skip the lathe class. No problem there. He was then handed two video tapes about milling operations, and told to watch them. It soon became obvious that there was no time for the instructor to leave the CNC class, and provide instruction on the manual Bridgeport milling machine.

So, John contacted the local Bridgeport dealer and purchased a manual for the machine—fully expecting that it would explain how to use the machine. After spending $35 on the thin blue book, it was clear that the “manual” was nothing more than a disorganized compilation of technical information—sheets that the Bridgeport Company had accumulated for many different versions of that machine.

Useful as they were, there was no information on using the machine. John remained at the trade school for two more semesters until it closed. During that time he became very proficient at tramming the milling machine, because he had to tram it every time he used it!

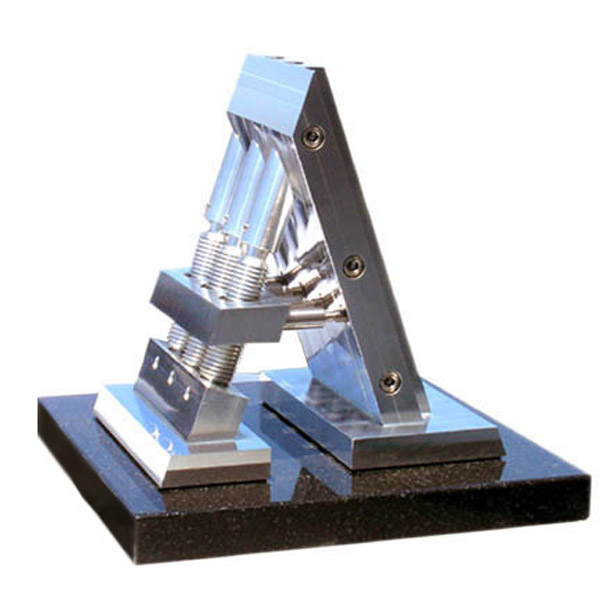

This piece is entitled, simply, “Capital Letter A.” The structural nature of this sculpture shows some influence from John’s 20 years in architecture. Machined in Aluminum, it’s 7” long x 8.5” wide x 9.5” high. It’s from an edition of 5, and weighs 7 lb.

Finally—Metalworking Machines of His Own

After the trade school closed, John decided to purchase a used Bridgeport milling machine. For many months, he found mostly worn out and pathetic machines. However, it turned out that the local dealer had just been traded back a machine that was sold to the University of Colorado 25 years earlier. It seemed that the machine was located in a physics lab, and although it was manufactured in 1968, it had hardly been used. It was in absolutely pristine condition!

Expecting that purchasing such a machine would include delivery, John was quite surprised to find out that he had to hire riggers, at a cost of $600, to load up the machine and have it delivered to his house. Delivery of that machine was an occasion the entire neighborhood would likely never forget. After having a semi tractor and trailer pull up with the machine, and a specialized fork lift, it became evident that fork lifts don’t work very well on steep icy driveways! Considering the hourly rate of the riggers, a few neighbors helped to clear a path through the ice, and the machine was subsequently placed in the garage.

After it was all done, one of the neighbors came up and said, “That’s a pretty fancy drill press you’ve got there!” Another neighbor, an 80 year old woman from across the street, knew exactly what was going on. Her father was a mechanical engineer who had worked with a Bridgeport milling machine. It turned out that she had a reasonably sophisticated wood shop in her basement, complete with several high-end machines. Not only that, but she really knew how to use them, and she could make anything known to humankind! Needless to say, that very nice lady was by far John’s favorite neighbor, and they became very good friends.

In the next few weeks, John hired an electrician to come over and wire up the phase converter. He leveled the machine, trammed it, and went to work. It was a great relief not having to lug all of his tools to trade school three nights a week. Over the next four years, John diligently worked with that pristine Bridgeport milling machine in every spare moment of his time. He could barely conceal his pleasure and joy. No more cardboard and paper models! As time went on, it became more and more obvious why no one was making artistic compositions from machined metal components.

First of all, many artists are not inclined toward technical disciplines. That said, it became very evident after making nothing but junk—for years—that simply acquiring a Bridgeport milling machine does not make one a machinist! Not only that, but an end mill that is the same diameter of a given drill bit is about eight to ten times the cost. All those little red Starrett boxes were quite an investment. The little blue Valenite boxes were even more of an investment.

So, the answer to John’s question began to reveal itself over time. No one was making artistic compositions with machined elements because learning the machining trade was extremely time consuming (as well as unforgiving), and the expense associated with the machines, tools, and materials was significant. That said, Mr. Gargano was not the least bit deterred.

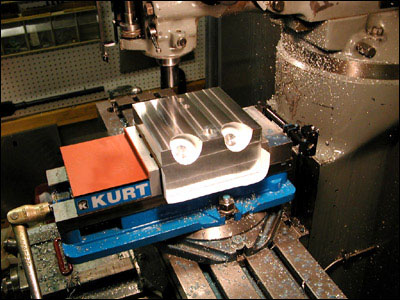

A final facing operation on the Bridgeport. The marks from the fly cutter would be left on the part, so as not to disguise the nature of the process used to create it—instead emphasizing it.

Now, just having a Bridgeport milling machine in his garage made John walk around with a grin like a Cheshire cat. It meant nothing to him that it was taking a great deal of time to become proficient. This was exactly what he learned growing up. Sticking with an activity that did not provide immediate gratification, but instead required a long-term concentrated effort—it required discipline.

John had already learned from all of his experiences in shop classes, and through working with his father, that nothing worth having came easily. Further, whenever one goes where they have not previously been, they are immediately bestowed the title of novice. If someone readily takes on that title, and honors it with an attitude of respect, the activity will provide a wonderful experience in the moment. And with the investment of time, there also comes a great feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment.

These feelings, which are absent among many of our young people today, in turn bring about feelings of security and self esteem. These feelings make one sure-footed and capable as they go through life. John believes that many so-called personality problems, which today are treated with pharmaceuticals, are in fact nothing more than deficits of self esteem and feelings of emptiness. He suspects that many people feel this way for not taking on, and prevailing through, objectives that require discipline and hard work.

Objectives of this type are not honored in a culture of instant gratification. While many people shy away from adversity, Mr. Gargano believes that only through embracing and overcoming adversity, with the proper attitude, can one realize their fullest potential in life.

John refers to this sculpture as “Whimsical 01,” which can be a description, a name, or both. Either way, it definitely took his work in a different direction.

After working with the Bridgeport milling machine for four years, John decided to purchase a lathe. He looked on eBay, and inspected various types of used machines in the region. Since Colorado was not known as a hub of industry, suitable machines were not readily available. But one day John found the perfect machine. It seemed that a local gentleman, who was an EMCO aficionado, had decided to rebuild one complete machine from three used machines as his first retirement project. The man disassembled each machine, inspected the parts under magnification, selected the best ones, and vibratory cleaned each one.

He then purchased German SST metric socket head cap screws to replace the black oxide fasteners that came with the original machines. When the gentleman couldn’t find acceptable parts from one of the three used machines, he acquired original parts from the manufacturer. All told, aside from new paint, the final machine was mechanically perfect, and extremely accurate. Mr. Gargano considered this machine to be a treasure, and he used it on every one of his machined metal sculptures.

It All Comes Together as Art

After having worked with both machines for another year, John decided to begin his first machined metal sculpture for public consumption. That sculpture, “Stiletto,” was meticulously produced over the course of the next year. Stiletto was machined from steel, and the parts were nickel plated. Because he developed tendonitis from handling the heavy steel cubes, John would work with aluminum moving forward.

Eventually, John started producing machined metal sculptures that typically required months to complete. A unique feature of John’s work is that he rarely removes the machining marks. Instead, the machining marks are carefully and consistently made to reveal the true nature of the process. This is consistent with the Bauhaus orientation, which honors the true nature of a material, and resists decoration or adornment.

When beginning a new piece, John learned to stay away from thinking about when it would be completed. That type of thought process is bothersome, and not conducive to making high quality parts. When people asked when a given piece might be finished, Mr. Gargano would simply smile and say, “I don’t know.” Consideration of dates and times of completion are not an integral part of the creative process.

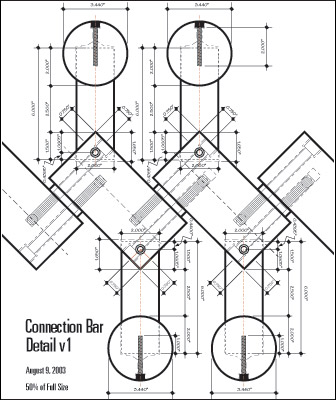

Four years after making his first piece, John had produced only seven pieces of machined metal sculpture. For each project, he carefully prepared detailed measured drawings and instructions. Each sculpture is an attempt to execute an all encompassing piece of art, and one which addresses both the technical and aesthetic aspects of the task.

John’s work has twice been accepted into the Rocky Mountain Biennial Juried Art Competition, which covers a seven state region. His “Stiletto” sculpture received an honorable mention in that competition. John has also exhibited his work in other fine art galleries, and his sculptures were accepted for exhibit at the Cherry Creek Festival of the Arts in Denver, Colorado. At the time of this writing, he had received two commissions to create pieces for specific art collectors. Most recently, after having moved to Florida, John exhibited his work in Naples as part of the Saturday Art in the Park Program. His piece entitled, “Barton,” was also accepted into the All Florida Juried Exhibit and Competition in June of 2007.

Art as a Universal Principle

Art is anything someone does as a form of expression. Throughout recorded history, fine art has provided viewers with a dimension of experience beyond one’s everyday occurrences. While some may debate and deliberate about whether or not a given piece of art is beautiful to them, people have learned to appreciate that which may not appeal to them if it exhibits merit, talent, or dedication on the part of the maker. This is a universal principle. Mr. Gargano creates art that embodies the values and principles that have defined his life.

Every piece of a given sculpture is a carefully executed composition, which expresses in machined metal the same things composers try to express with music, or poets try to express with words. Unlike many of the contemporary artists of the last fifty years, John has endeavored to challenge himself, as opposed to his audience. He enjoys seeing work of any kind that embodies the principles of discipline, dedication to learning, and the time honored practice of craft.