January 8, 1938—August 29, 2009

Designing, Building, and Providing Plans for Model Engines

Introduction

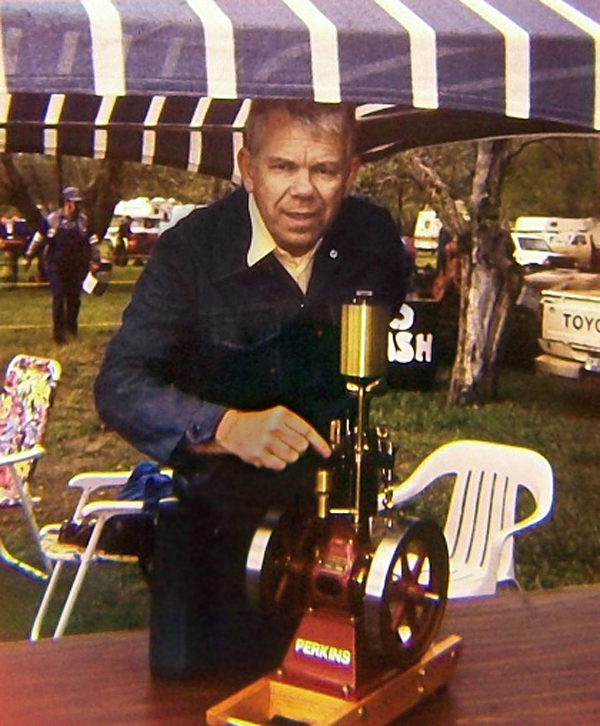

Jerry Howell was well known in the model engineering hobby for many years. He attended the North American Model Engineering Society Expo (NAMES) and a number of other shows almost every year, with a beautiful display of engines he had designed. Mr. Howell’s original engines undoubtedly grace many desks and mantels of proud builders around the world. When looking at the finish of Jerry’s own personal projects, it’s clear that he was not satisfied with anything less than perfection. His work is truly beautiful. More important to the Joe Martin Foundation, however, is the fact that Jerry went beyond just making his own engines. He also designed and produced plans and kits so that others could make them, too.

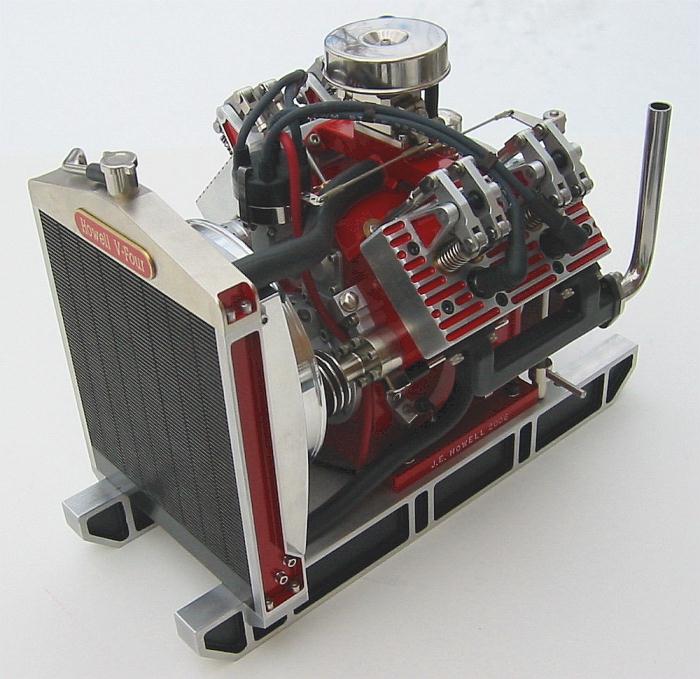

In fact, even Jerry’s plans go above and beyond the typical engine kit. That’s because they often show complicated parts at several stages of completion, making it easier for novice builders to comprehend. We were impressed enough with one of Jerry’s later projects, the Howell V-4, to make it one of the Craftsmanship Museum shop projects.

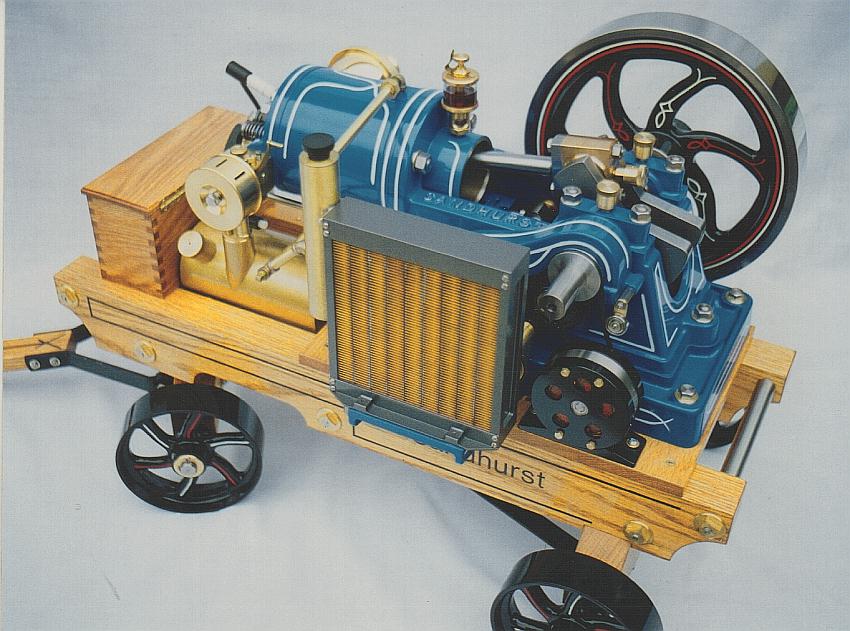

This Stuart Turner Sandhurst engine has a bore of 2” and a 3” stroke. Jerry made his own designs for the radiator, fan, centrifugal water pump, and pumping throttle. This engine was featured on the cover of the June, 1999 issue of Gas Engine magazine, with an accompanying article.

Building Models at an Early Age

Jerry Howell was born and raised in Central Ohio. From a very early age, he was always interested in mechanical things—especially miniatures. However, it wasn’t until Jerry was in his 50’s that he found out where that trait probably came from. Jerry’s dad told him about his grandfather, who had built a scale model of a house he was going to build. The model included all the studs, rafters, etc. Jerry’s grandfather then used the refined and proven model to actually build his full-size house.

Growing up, Jerry had several electric train sets, which led to a fascination with steam locomotives. In his teen years, around the early 1950’s, Jerry would regularly make wooden ship models, box kites, electric boats, balsa wood gliders, rubber-powered model airplanes, homemade firecracker guns, and soda straw rockets. Some of the soda straw rockets had two or three stages, and flew several hundred feet high.

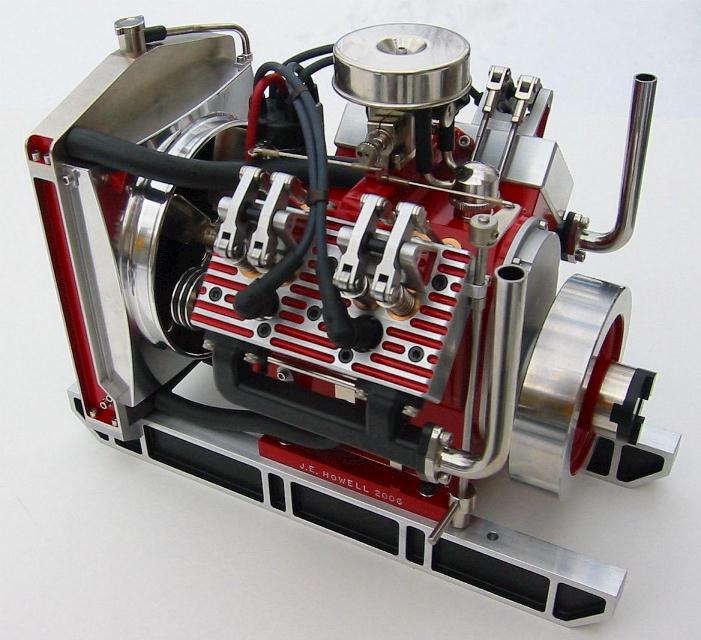

Jerry’s namesake Howell V-4 engine is 1.95 cubic inches (32 cc) displacement. The cylinders are 90° apart in order to balance the engine for vibration free running. The cylinder bore is .875”, and the piston stroke is .812″. The cylinder banks are not staggered. Robust knife and fork connecting rods were used.

A Hall effect distributor is driven off the end of one of the cam shafts. The multi segment built-up crankshaft and twin cam shafts are amazingly easy to make. The distributor body is linked to the throttle arm for spark advance/delay with the throttle setting. The throttle is Jerry’s proven 2-jet design, with an oiled foam air cleaner.

In metal shop, Jerry turned a brass Naval cannon barrel, which led to an interest in machining. Around the same time, Jerry began checking out every book he could find at the local library about steam engines, rockets, jets, astronomy, and telescope making. His best school subjects were physics and chemistry. Looking back, Jerry said he was positive that all of those things together had a large influence on his later endeavors. After high school, he would go on to work for his father.

Jerry drove one of his dad’s milk trucks, picking up 10-gallon cans of milk from farms seven days a week. As a young adult, he got into flying control line model planes, and then R/C planes and boats later on. In 1960, he acquired a 3” Unimat lathe which rekindled his interest in machining. Jerry used the lathe to build fuel filters and several throttles for his two-stroke engines. In doing so, he was able to improve the idle reliability.

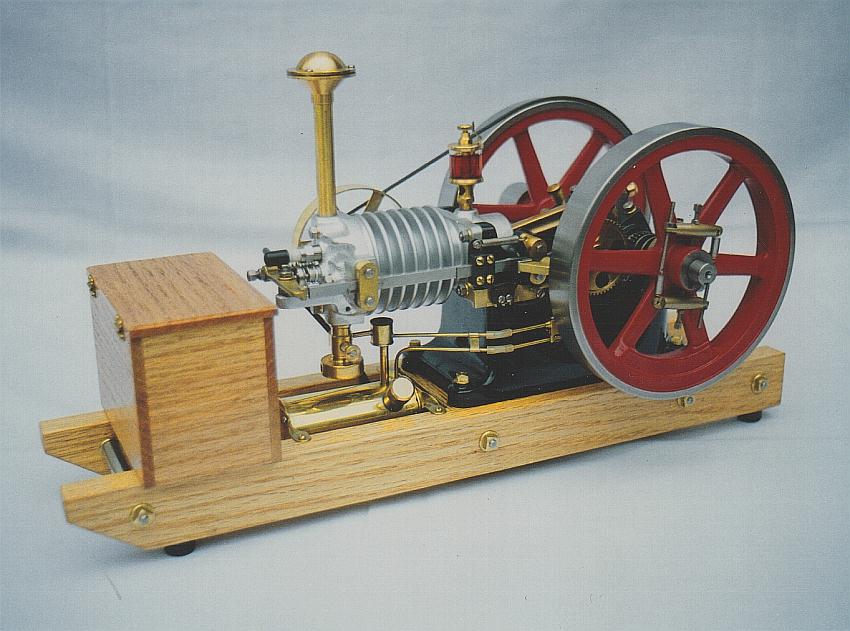

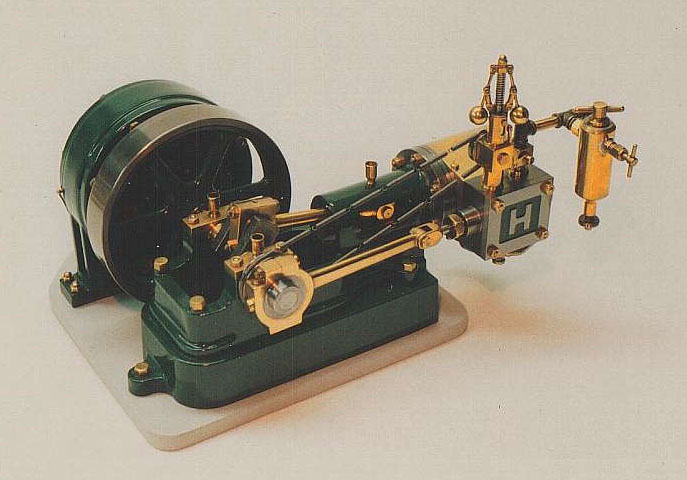

This No. 10 horizontal steam engine was made from a Stuart Turner casting kit. Jerry added his own 8-pole DC generator, working fly-ball governor/steam throttle, and a lubricator.

A Career Change Brings Machining Back Into the Fold

Jerry never cared much for driving the truck, so when an opportunity came about in 1962, he jumped on it. Jerry took a job in Jacksonville, Florida as an apprentice making plastic injection molds. He stayed there for a few years, learning a lot about machining and operating full-size lathes, mills, and other tools. During that time, Jerry made his first engine—a small 1/4” bore oscillating steam engine. He made it from bar stock on his kitchen table.

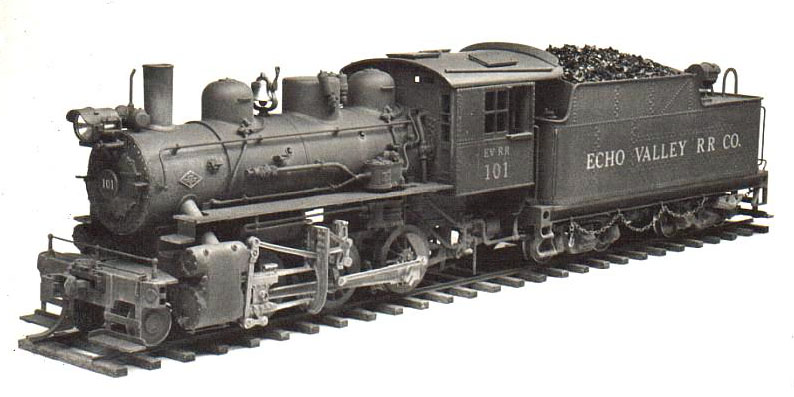

After a few years, Jerry moved back to Ohio, and eventually bought and operated a construction equipment business. At that point, his main hobby interest turned to HO model trains for a few decades. Jerry’s scratch-built 0-6-0 switch engine was an early Model Railroader magazine “Model of the Month” winner.

Switching to Computers and Adding CAD to the Toolkit

In the early 1980’s, Jerry sold the construction equipment business and opened a computer store. He learned about CAD software, and started using Draft CAD Ultra to design many of his projects. In fact, Jerry said he wouldn’t have wanted to make most of his later projects without the use of CAD software.

Shortly after, Jerry became interested in “hot-air” engines, both Stirling cycle and atmospheric (or vacuum). He began building many different types of these engines. As he went along, Jerry found that he enjoyed designing engines just as much, if not more, than building and running them.

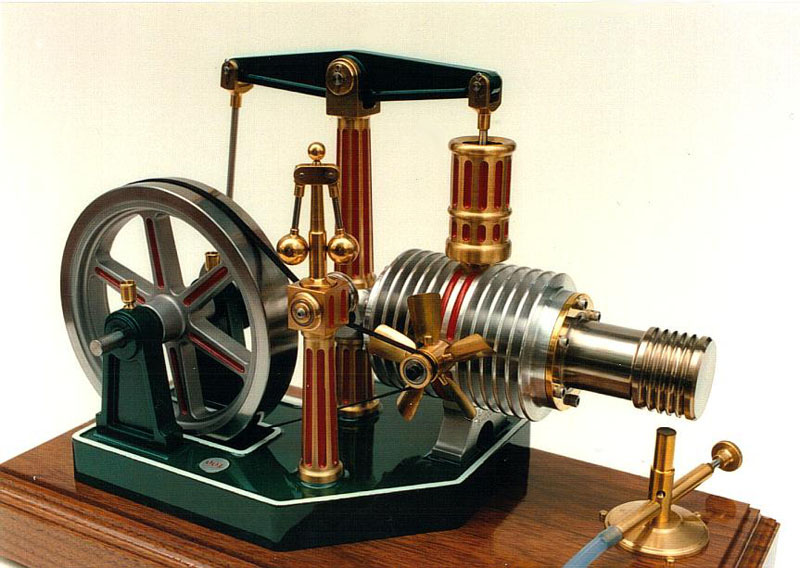

This engine, designed and built by Jerry, was produced as a “1 of 100” limited edition casting kit. The engine base, crankshaft supports, and beam are Petrobond sand castings. Everything else was made from bar stock. The flywheel is 4.3” in diameter. Dubbed the “Beamer,” this is a representation of a large Victorian style beam engine that could have existed in the mid-late 1800’s. The Beamer engine has a unique design, and nothing like it has been done before. A belt-driven cooling fan allows the engine to operate continuously at a temperature only slightly above ambient! All shafts are fitted with ball bearings for smooth running, and a maintenance free engine. An operating fly-ball governor, which is driven by the fan belt, adds another level of interest to the engine. However, it doesn’t actually regulate the engine speed. The Beamer runs at a leisurely pace powered by the flame of an alcohol lamp, or a propane burner as shown here.

Kit Requests Lead to a Full-Fledged Business

It didn’t take long before others in the model engineering community started asking for plans to build Jerry’s engines. In fact, it started with some of the early NAMES Expositions. At some point, Jerry came upon a used 1904 book showing the wooden cuts on beautiful late 1800’s Victorian era stationary steam engines. These engines really caught his attention.

Eventually, Jerry started incorporating that Victorian style into his own engines, concentrating more on the aesthetics. He also started designing his bar stock engines to look like they were made from castings as much as possible. At the same time, he didn’t want them to be too difficult for the average builder to make.

Jerry noted that a model made to be visually appealing only takes a little longer to build than a bare-bones one. His philosophy was that if it was worth doing at all, it should be made to look as nice as possible. Truly well crafted models will become valued heirlooms, to be handed down long after the builder is gone.

Now, Jerry wanted to make a few scale engines that just couldn’t be manually machined from solid stock. At least, they couldn’t be machined to look as if they were made from castings. Many of the parts were very small, so sand casting was out of the picture. Jerry’s solution was to make lost-wax castings.

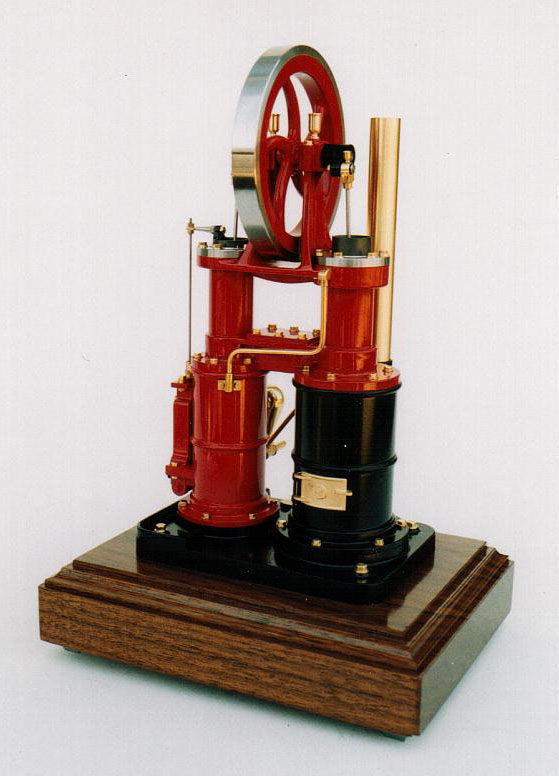

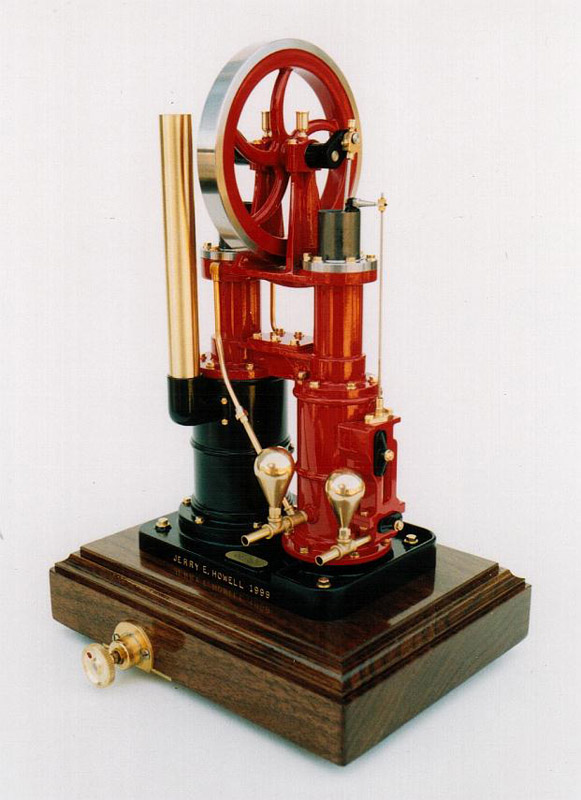

Jerry’s “Rider” compression pumping engine was made as a limited edition lost-wax casting kit, and only fifty were produced. The cylinders are stainless steel, with .600” diameter graphite pistons. Much of the balance of the engine comes from brass bar stock and tubing. The 3.3” diameter flywheel is a zinc alloy casting, with stainless steel rim. The two upper cross members are lost-wax castings, along with an 18 K gold fire door. The engine base is a zinc alloy Petrobond sand casting, which contains the kit’s serial number.

The double acting water pump is made from brass bar stock, and has a 3/16” bore. It also has two Delrin roller valves behind each of the black covers. All of the pumped water goes through the cold cylinder water jacket, and part of that water is diverted to the top of the hot cylinder water jacket for cooling. A small propane burner is inside the furnace.

A jeweler friend had taught Jerry about the very involved process of lost-wax casting. After purchasing a lot of high-priced equipment, Jerry made several detailed limited edition casting kit engines in both aluminum and zinc alloy. His favorite of these engines was the “1 of 50” serial numbered Rider compression pumping engine—which is now a collector’s item. (The Rider engine is pictured above.)

After designing many of the hot-air engines, Jerry’s interest turned to internal combustion engines. Having acquired larger machine tools over the years, Jerry decided to buy and build some antique model hit-n-miss engine casting kits (steam and internal combustion). Over time, he collected more than 25 of these kits, and built many of them. Those kit engines inspired Jerry to develop some of his own bar stock engines. He saw that there was a relative lack of non-airplane IC bar stock engines in the hobby.

Naturally, Jerry turned his attention to that deficiency. His first engines were single cylinder. Later came the air-cooled 90° V-twin, and the liquid-cooled V-4. The V-4 features twin cams, a Hall effect distributor, pressure feed oil system, magnetic drive water pump, and a water-heated intake manifold.

Jerry always wanted his IC engines to serve some kind of purpose while running. Many others have geared or belted their engines to can crushers, peanut roasters, water pumps, etc. However, having a fondness for stationary industrial engines, Jerry decided that a generator was about as practical and clean a load that could be driven by a model engine. Also, a permanent magnet generator (actually a DC motor) doubled as a starter motor. After 1995, all of the prototyped IC engines that Jerry designed included a starter/generator as standard equipment.

Along with his engines, Jerry made this miniature precision drill press entirely from bar stock. It features a quill depth stop, quill lock, 2” travel depth indicator, variable speed DC motor, 3-step pulleys, and electromagnetic base.

In short time, these became Jerry’s trademark engines at shows. Over the years, he attended more than 50 model engineering shows. In that time, Jerry was able to meet some of the finest folks on earth, and more than a few became close friends. Model engineering is truly one of the world’s great hobbies! Jerry considered it a great honor that the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum chose his Howell V-4 as our second team build project. Watch a YouTube video of Jerry running his Howell V-4 engine at the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum.

In October, 2007 Jerry (left) visited with founder Joe Martin (right), and shop craftsman Tom Boyer at the Miniature Engineering Craftsmanship Museum. Jerry’s red Howell V-4 engine is sitting on the table next to the recently completed Seal Engine— which was made as our first museum team build project.

Jerry’s Workshop

Even after many years, Jerry held on to his original 1960 Unimat DB200. Although, the lathe was only being used for polishing with a buffing wheel for the better part of 20 years. Jerry also owned a Maximat 7 and Maximat Super 11 lathe. In the mill department, he used a jet JVM-836 (manual with Mitutoyo DRO and 6” Kurt Vise). He also used a Jet JVM-836 mill that he converted to CNC with ball screws.

Jerry did the CNC conversion in January, 2007. His first CNC project was to mill the skids and the exhaust rain caps for the Howell V-4 engine. Jerry used his mills for drilling large holes, and his own mini drill press for everything under 1/4”. He also had a cantankerous old Jet 5” horizontal/vertical bandsaw, which Jerry said he was ready to take a sledgehammer to!

Jerry’s 1990 Emco Maier Maximat Super 11 lathe. He also made the bench, with removable chip tray and backsplash.

View more photos of Jerry Howell’s exceptional model engineering.