Master Live Steam Model Engineer

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2018

The Joe Martin Foundation selected model engineer Charles “Chuck” Balmer, of Ohio, as the Craftsman of the Year for 2018. His work was honored at the North American Model Engineering Society Expo in Southgate, MI. The award included a check for $2000.00, an engraved gold medallion, an award certificate, and a commemorative book.

Mr. Chuck Balmer. Craftsman of the Year for 2018. Photos used on this page are courtesy of Chuck Balmer, Lee Hodgson, and Craig Libuse.

Introduction

Over the years, the Joe Martin Foundation has honored miniature craftsmen of all kinds. The foundation has featured the work of professionals ranging from clockmakers, jewelers, engravers, gunsmiths, dedicated model making amateurs, and more (amateur here meaning simply that they are unpaid, not unskilled). However, museum founder Joe Martin’s favorite form of craftsmanship was that done by home shop builders. Mr. Martin appreciated those craftsmen who worked simply for the love of creating an object of beauty—regardless of how long it might take, and what new skills would be required for the job. This is why the foundation’s overall focus often returns to the hobby of model engineering, where many devoted, often self-taught craftsmen invest their spare time.

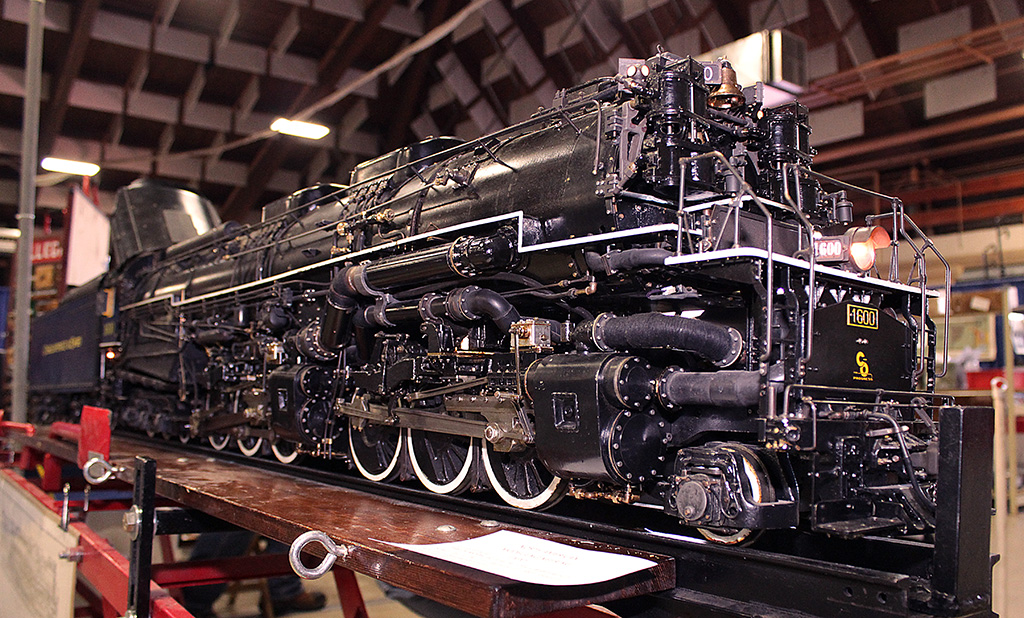

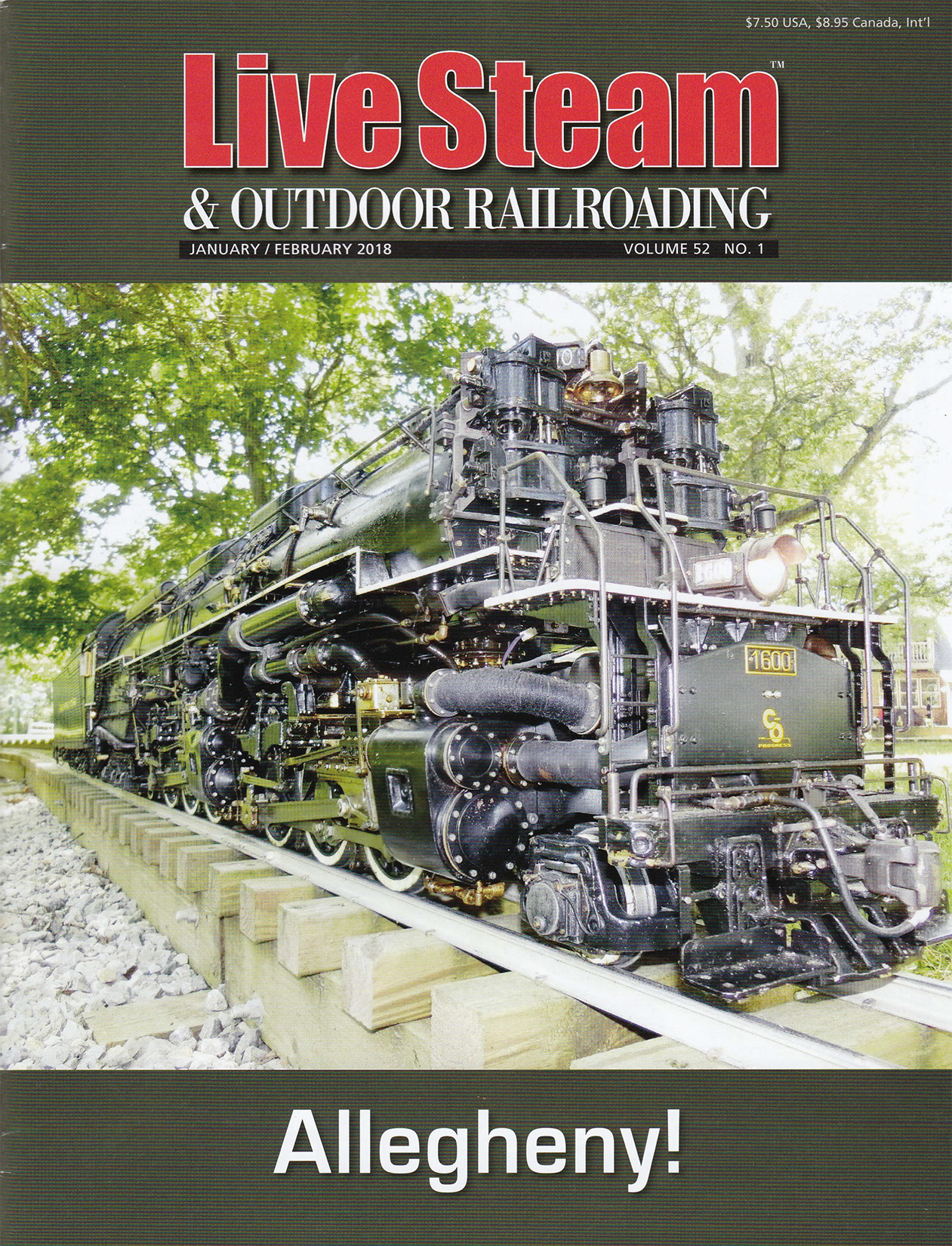

In general, model engineering typically involves building a miniature running engine of some kind. Steam engines, in particular, are among the earliest and most popular projects for model engineers. Building a running engine faithfully to scale is a challenge—getting one to run well is an art. The smaller the scale, the tougher the job. Chuck Balmer’s remarkable 1:16 scale Allegheny meets the challenge, and then some.

Chuck Balmer posing with his most recent, and perhaps most ambitious finished project: a 2-6-6-6 Allegheny on the 3-1/2” gauge club layout.

A Model Engineer Nominated by Fellow Club Members

Now, the foundation was introduced to Mr. Balmer’s work when several members of the “Cinder Sniffers,” a steam model railroad club in Ohio, sent along some photos of Chuck’s work. It was immediately clear that Mr. Balmer’s work was some of the very best in the field of miniature live steam locomotives.

To offer some background on Balmer, a few of his craftsmen colleagues weighed in on his achievements. In his nomination letter to the museum, the Cinder Sniffers club president Donald Frozing had this to say about Balmer:

“Chuck’s work is without parallel, and his contributions to locomotive modeling are immense. He is most recognized for his 1:16 scale Allegheny—a tour de force in modeling that required him to create parts from measurements and photos, build his own patterns, and cast parts in his home-built foundry. This locomotive is in the small 3/4” scale—the small end of rail park locomotive construction. He is a prolific and meticulous builder who is a resource and mentor to other builders. Enclosed is a nomination with further details. We believe Chuck Balmer epitomizes the Joe Martin Foundation Ideals.”

Mr. Frozing also noted the following:

“Chuck Balmer epitomizes the technical skill, extensive research, and attention to detail that fine miniature modeling requires. This is coupled with an enthusiastic willingness to share his expertise with fellow modelers. He is a retired electrical engineer, who, at the start of the space age, designed aerospace testing equipment, data systems, and even robots, while preserving the technology of the railroad age through painstakingly accurate work on locomotive models. The jewel of his collection is a 1:16 scale 3-1/2” gauge live steam model of the famous 2-6-6-6 Allegheny locomotive, built by the Lima Locomotive Works in Lima, Ohio. This effort took 14,000 hours, and more than seven years to complete. Balmer was inspired to model steam engines by memories from his youth of watching The Wonderful World of Disney on TV, as Walt drove a scale steam locomotive around his property. After graduating from the University of Dayton in 1968, he built and equipped a home machine shop and electronics lab; built a foundry to cast his own parts; learned pattern making and welding; and honed his machining skills by building a stable of locomotives in the small 3/4” scale, as well as two robots.”

A low angle shot of Balmer’s model Allegheny gives an idea of how impressive the real thing must have been coming down the tracks.

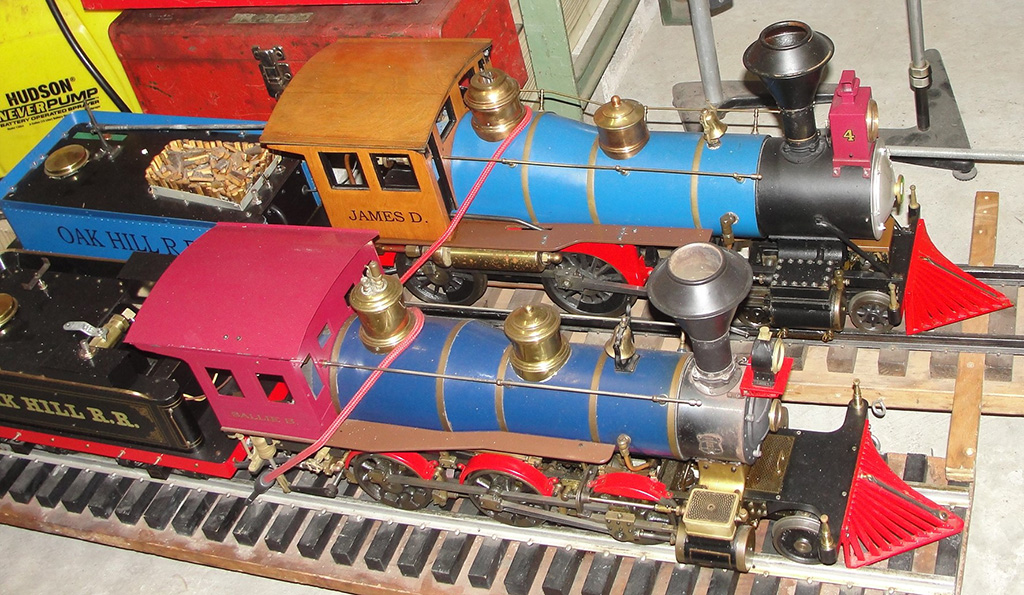

Chuck Balmer’s collection of models and robots includes:

- An NYC 4-6-4 Hudson steam locomotive, completed in 1971.

- The “Pidge” locomotive, an 0-4-0 Switcher completed in 1973—the year Balmer and his wife, Julie, were married. (Pidge is Julie’s childhood nickname.)

- An EMD F7 Diesel electric locomotive, completed in 1975, based on copious photos he took of an Erie Lakawanna F7 that was on its way to the scrap yard.

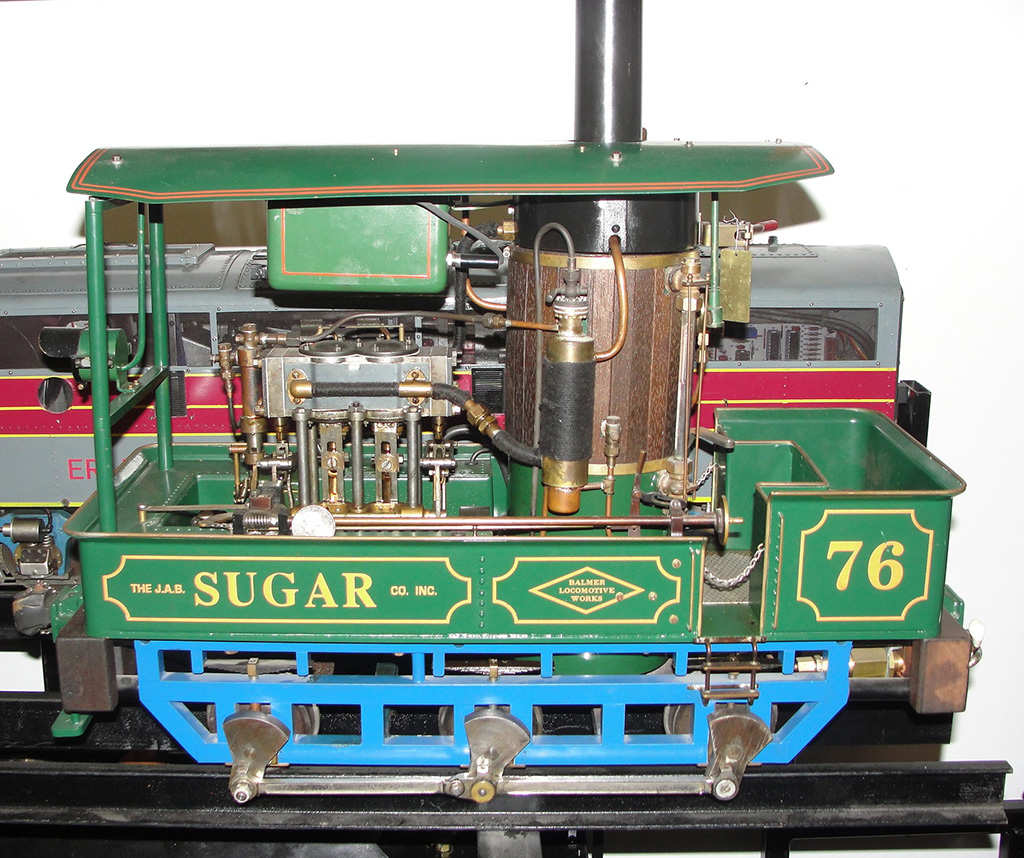

- The “Sugar,” an 0-6-0 vertical boiler plantation engine completed in 1976.

- The “Allegheny” 2-6-6-6 articulated engine, completed in 2013. It’s 8 feet long, and weighs 350 lbs.

- An SD70 “Ace” diesel electric locomotive in BNSF colors, completed in 2014.

- An 0-6-0 gasoline powered boxcar switcher in 1-1/2” scale, completed in 2017.

- Another 7 additional engines acquired from other sources, that have been either restored or completed by Balmer.

- 9 different railcars, including riding cars, freight cars, and a caboose.

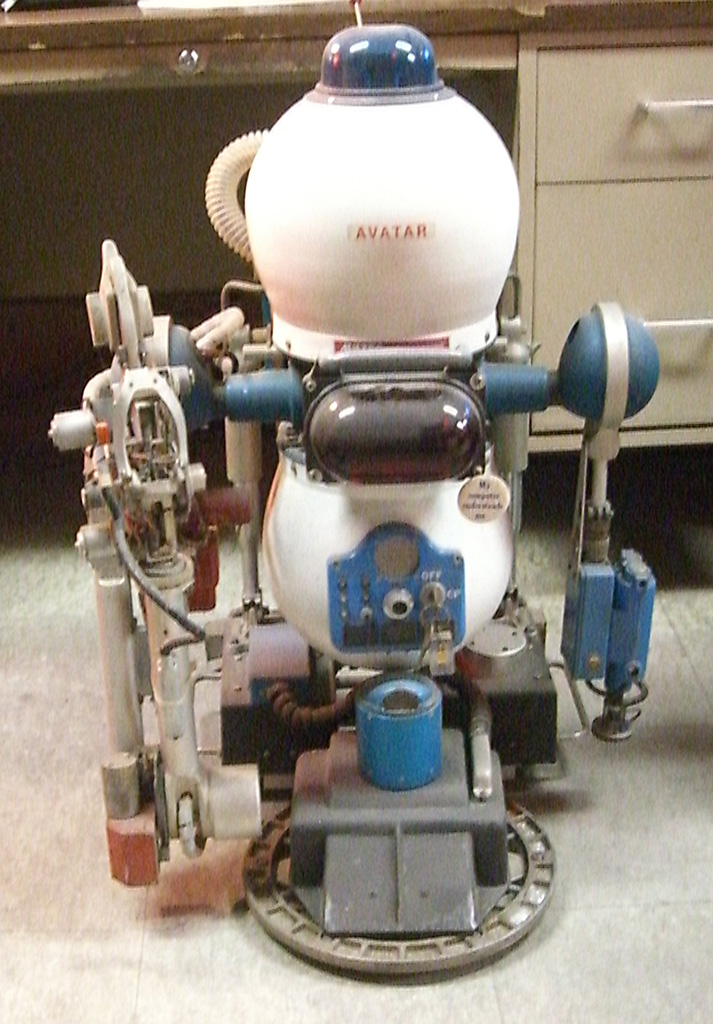

- The “Avatar,” a knee-high robot that received the 1982 Robot of the Year Award by Robotics Age magazine. It was displayed in the Boston Computer Museum for three years. Avatar was written about in several publications, including The Wall Street Journal.

- The “Huey,” a 12-inch tall autonomous robot built in 1992 that wanders through Balmer’s shop, mapping its course and then backtracking home to its charging station. Huey is programmed to remind Balmer of birthdays, anniversaries, and holidays.

Although the robots are not models, they are powerful examples of Balmer’s miniature machining and design skills. The Diesel engines mimic full-size engines with an internal combustion engine driving a generator with appropriate electronic controls. Few diesel models are so internally accurate.

Balmer had first seen the massive, full-size Allegheny in the Henry Ford Museum in 1963. It sparked a passion to build it in miniature. In 1977, he purchased a set of 100 blueprints of the Allegheny, which showed basic schematics, but few part details. Family visits included hours of research at the Allen County Historical Museum in Lima, Ohio. After photographing and measuring the full-size engine in the Henry Ford Museum, Balmer was able to create the needed part designs and dimensions in sketches that fill a thick binder.

Parts ranged from a 4-foot long copper boiler that took a week of 8-hour days to machine, and generated 28 pounds of copper shavings, down to tiny fittings no bigger than a fingernail. Balmer also made 59 wooden patterns. Then, over two summers, he and his son, Jim, made more than 100 castings. Building fully functional miniature steam locomotives often poses daunting engineering and design challenges.

The Allegheny, like most of Balmer’s other engines, runs on steam. This creates additional issues dealing with heat and expansion, as steam and water do not scale. All of his engines run, and are regularly seen steaming around the Cinder Sniffers Rail Park in Indiana, as well as Balmer’s backyard track in Urbana.

Chuck Balmer is a master designer, as well as a master builder in miniature. He is also a champion of the work of other model builders. Several aging model builders, and widows of model builders, have turned to Balmer to complete locomotives that would have otherwise been scrapped. Finishing a partially completed project can be more challenging than building your own. Balmer has resurrected seven locomotives, ranging from rebuilding once-running engines, to completing locomotive projects that were only 20% underway when they came into his shop. —Donald Frozing, President of the Cinder Sniffers Steam Model Railroad Club

Balmer’s Allegheny was featured in the Jan/Feb 2018 issue of Live Steam magazine (Article reproduced here with permission from Live Steam magazine.) Watch a video of the Allegheny’s first live steam run below. Additionally, you can also view another video of the Allegheny running on the Cinder Sniffer track.

Chuck Balmer’s Path to Craftsmanship

A Love of Trains Since Childhood

Like many young boys raised in the 1950’s, Chuck had a Lionel train set which he loved. His family lived just two blocks from the train tracks in Urbana, Ohio, and he would go down and watch the steam locomotives switch cars around in the yards. He moved on to HO trains for a while, but then got interested in electronics at around twelve years old, and temporarily put trains aside. Chuck had seen Walt Disney’s backyard steam railroad on TV, and a seed was planted that would later flower into the live steam hobby that Chuck would enjoy for years to come.

Chuck has been building live steam locomotives for quite some time. In this photo, he’s at the controls of one of his earlier projects—a NYC 4-6-4 Hudson. It was completed in 1971.

Developing Skills in Electronics Leads to a Career

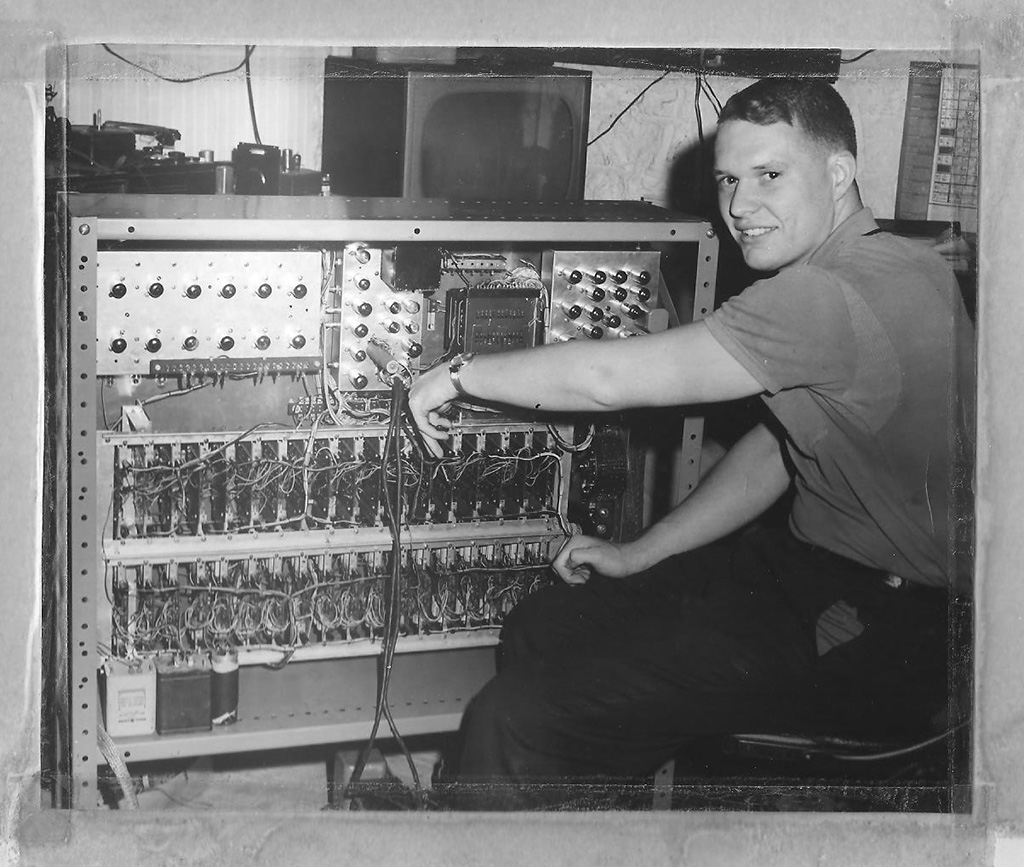

As a young boy, Chuck built many models—some plastic, and some scratch-built. When he got to grade school, Chuck became interested in electronics. He built a number of radio transmitters, radios, audio amplifiers, and eventually computers using vacuum tubes. Chuck continued to build radios, and even worked for a local TV repair shop at an early age. He continued doing TV repair into high school, where he began building computers as well. In fact, some of his computers won superior ratings in state science fairs.

Chuck also built his first robot in high school! While an undergraduate at UD, he built another small robot, and several other computer related projects. Chuck was also offered a part-time technician position in the instrumentation department at the UD Research Institute. Additionally, he built a fuel injection system for his Triumph motorcycle, and wrote an article about it for the UD Engineer magazine— which won a prize for the best article published that year.

Following his graduation, Chuck built his first locomotive, and proceeded to build three more by 1976. In 1972, Chuck designed the first 16-channel digital multi-train control system for electric trains. The system was known as the DIGITRAK 1600 multi-train control, and was featured in an article in Model Railroader magazine. Chuck then started a company called Electro-Plex Inc. and marketed these controllers for several years.

When Chuck initially graduated from UD in 1968, he received his BSEE degree, and went straight to work as a contract engineer at Wright Patterson Air Force base. He then moved on to Grimes Aerospace as a project engineer. At Grimes, Chuck worked on an aircraft proximity warning system, among many other projects. While employed there, Chuck would also earn his MSEE degree, and eventually moved on to work for an instrumentation company. In that role he designed data acquisition equipment. Having also started their microcomputer program, Chuck became software engineering manager, and was responsible for developing large data acquisition systems.

In 1982, he left the company to strike out on his own. While slowly developing a consulting customer base, Chuck taught a computer course at Ohio State University, and also took on contract engineering jobs. He continued running his own business for 25 years, specializing in the design and manufacture of electronic production test equipment for the aerospace industry. Chuck officially retired in 2006, but was still doing some consulting for one of his long-time customers at the time of this writing.

This diesel/electric Burlington Northern Santa Fe engine is also a part of Balmer’s collection, seen with two other engines.

Star Wars Inspires Work on Robots

When the movie Star Wars came out in 1976, Chuck’s focus shifted back to robots. He built a robot named Avatar, and won a contest in 1982 for an article on the best home built robot from Robotics Age magazine. This robot was put on display for 3 years at the Boston Computer Museum. While it was gone, Chuck built another more complex robot named Huey in 1992, which was still roaming his shop at the time of this writing.

Getting a Start in Metalworking

Now, Chuck first learned how to use machining equipment in the mechanical engineering department at the University of Dayton, making fixtures for the test equipment he was building. After graduation, he decided to put together an electronics and mechanical laboratory at home, where he could pursue his own projects. The first mechanical project was a 3-1/2” gauge 1:16 scale model of a New York Central 4-6-4 live steam locomotive.Chuck learned most of his mechanical and metalworking skills on his own, and with a little help from his brother-in-law who was a tool and die maker.

A Return to Live Steam Locomotives

After retiring in 2006, Chuck returned his focus to the live steam hobby, and began building the Allegheny 2-6-6-6 locomotive. This project took seven years full-time to complete (14,000 hours). Before 1976, Balmer had scratch-built four locomotives. Since 2013, he has scratch-built three more locomotives, restored or completed another eight, and built seven different train cars to go along with them.

Learning the Casting Process

Moving forward, Chuck ran into some problems when he needed to make castings for another locomotive. He purchased a small furnace, some books on casting, and began learning how to make his own patterns and molds. Eventually, Balmer would need a bigger furnace, so he designed and built one of his own—which was still in use at the time of this writing. Over time, and learning from experience, he was able to develop his own techniques for making castings. Mr. Balmer even created a video explaining the casting process, from making patterns to pouring metal. Chuck went out of his way to share his experience with other craftsmen.

Advancing His Welding Skills for the Allegheny

Now, Chuck learned to gas and stick weld when he built his first locomotive. However, when building the Allegheny, he realized that he needed to learn how to TIG and MIG weld, too. So Chuck and his son enrolled in an eight-week course at the local vocational school. The course provided them with the basics of TIG/MIG welding, and they were even able to bring in the chassis of the Allegheny for final welding. Eventually, Chuck bought his own welding equipment so he wouldn’t need to rely on the school’s workshop.

Building a Home Workshop

Later in his life, around 1972, Chuck bought a piece of property and built a 24’ x 30’ frame building. He then moved all of the equipment he’d acquired—which was in his parents’ basement—into the new building. The interior was organized into an office area, a machine shop, an electronics lab, and a foundry area! Over the years, two additions were added to accommodate the welding area, stock storage, and to make room for Balmer’s many locomotives.

In addition to the many specialized hand tools acquired while building test equipment, Balmer also has three metal lathes. These lathes range from a small Unimat for very tiny parts, to a WWII vintage 5” South Bend thread cutting lathe for bigger pieces. Chuck also has a small vertical milling machine, as well as two drill presses. All of the lathes and the mill have been outfitted with digital readouts on all axes. The shop also has a 1.5 ton arbor press, a 20 ton hydraulic press, and a 24” sheet metal sheer, brake, and roller.

Other equipment includes a 14” band saw, a horizontal power hack saw, and a 16” scroll saw. The welding area utilizes a Miller 200 amp TIG welder, a Hobart MIG welder, a band saw blade welder, and an acetylene welding set. The foundry consists of a propane-fired furnace capable of melting eight pounds of cast iron, and additional equipment for preparing casting sand and making molds.

The electronics area of the shop has several computers, three oscilloscopes, a function generator, several power supplies, several types of meters, soldering equipment, and a selection of thousands of electronic components. However, perhaps Balmer’s most important asset is his understanding wife, who shares his enthusiasm for trains, and has fully supported Chuck’s shop activities!

View more photos of Chuck Balmer’s award winning craftsmanship.