Striving for Perfection in Model Engineering

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2017

Cherry Hill (left) accepts The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award at the Centenary Model Engineering Exhibition in 2007. The award was presented by Chief Judge, Ivan Law. The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award is the highest honor given in the UK for model engineering. Cherry has won the award 9 times!

Introduction

When Joe Martin first began working to establish a non-profit organization to honor fine work in miniature and model engineering, we also began a search for the world’s best model engineers. That search started mainly with people we were familiar with inside of the United States. Having attended model engineering shows in the US for many years, representing his line of Sherline precision miniature machine tools, Joe was acquainted with many world-class model makers and engineers—as well as their work.

However, Joe also recognized that some of the world’s finest model engineering projects are built in England. Joe asked around among those who had traveled or shown their work internationally. He wanted to find out whose work outside of the US might be considered “the best of the best.” One name kept coming up—Cherry Hill.

Photos used in this article are courtesy of David Carpenter, Norman Mays, Cherry Hill, The Institution of Mechanical Engineers, and Model Engineering Magazine (My Time Media).

To be certain, the world of metalworking and machinery—as well as the hobby of model engineering—have traditionally been male-dominated fields. So, it came as a bit of a shock to many that the very best in their field might be a woman. However, none seemed dismayed by this, and Mrs. Hill’s work has been primarily met with intrigue and amazement. Who was this woman building these incredible working scale models of ornate Victorian traction engines?

Now, for those who want the full details, and an extensive sample of fine photos of Hill’s work, we recommend David Carpenter’s book entitled, Cherry’s Model Engines—The Story of the Remarkable Cherry Hill. (The book can also be found on Amazon.) The hardbound book tells her story, and is packed with photos that do justice to Cherry’s award-winning work. David and Mrs. Hill have given us permission to use some of the copy and photos from that book here to give a brief introduction to her work.

Indeed, no website proclaiming to honor model engineers would be complete without reference to Cherry Hill and her models. The information obtained from David’s book and used here was correct as of the 2014 publication date. However, in our most recent communication with Mrs. Hill, she professed that she was finally going to slow down a little, as the demands of extremely fine work on her eyesight and fine hand skills have taken their toll—but only after some 60-odd years of world-class model engineering!

What may be her final major project, a Nathaniel Grew ice locomotive, was a work in progress at the time of this writing. Fortunately for those who appreciate fine model engineering, the body of her lifetime of work will continue to set the very highest standard for other model engineers to strive toward. Also, the results of the extensive research she has done on vintage engines will be preserved in her models.

Getting Started in Metalworking

To start, Cherry was the daughter of George Hinds, an agricultural machinery manufacturer. In 1936, he started a business in Worcester manufacturing hop-picking machines. However, the outbreak of WWII would bring a close to that business. With machinery in short supply, George and his equipment (including a Pittler lathe dating from 1914) were relocated by the government to the Royal Aircraft Establishment, in Farnsborough. In 1946, they would return to Malvern. Cherry was just 7 years old when the war broke out, and her father’s 1914 Pittler lathe was still in her workshop over a century after it was built.

Now, Cherry’s first model was made at the age of 9 or 10. It was a small wooden chest of drawers. Then, at age 11 she made a scooter, which gave her experience using nuts, bolts, and threads. Like many children building models of warships and aircraft during the war, Cherry built a model of a Sunderland flying boat—which received special mention in a model contest. After the war, she purchased a secondhand 2-cycle Excelsior motorbike—despite parental objections. This was soon replaced by a 250cc 4-cycle Matchless.

After graduation, Cherry joined the family firm building hop-picking machines. When her father died in 1961, the company was purchased by a larger group, and she worked with Bruff Engineering until 1975. Cherry then worked for a weighing and packing company in research and development until 1984—when she married professional toolmaker and fellow model engineer, Ivor Hill.

Cherry’s interest in engineering as a hobby had been stimulated during her vacations from the university. On those breaks, she built a custom car based on a 1926 Humber. The chassis was narrowed by 8 inches, and shortened by 26 inches. Also, Austin 7 axles and wheels were fitted. She also built her own hydraulic brakes, duralumin bodywork, and registered the car for road use in 1954. Eventually, she traded the custom-built car for a 1936 MG TA. After that, Cherry owned a series of British sports cars.

Cherry’s 1/16 scale model of an 1870 William Batho 25-ton road roller, built between 1983-1986 (approximately 6,000 hours). It weighs 22 lbs., and has the following dimensions: 15” x 7-3/4” x 9-1/2”. The model was awarded a gold medal and the Aveling Barford Trophy in 1987. It also won The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award for 1990.

Additionally, Cherry also went on to invent and patent a carburetor balancing device for pairs of SU carburetors. It was called the Crypton Synchro Check, and was manufactured by AC Delco. Original versions are still sought after among classic car enthusiasts.

However, in 1953 Cherry’s interest in engineering shifted back to scale models with the purchase of a Stuart No. 9 steam engine casting kit. She built the kit in 18 months between 1956-1957. Watching the engine come to life after making minor adjustments to improve the scale appearance left Cherry, “thrilled to bits.” She noted, “For the first time, I experienced the amazement that I had managed to build an engine that ran!”

In 1964, that model won a bronze medal at a model engineering exhibition at a London hotel. It now resides with the Society of Model and Experimental Engineers (SMEE). Both Cherry and her late husband Ivor were longtime members of the organization. That first model changed the direction of her model engineering career, eventually leading to an interest in ornate Victorian traction engines. These Victorian engines became her main focus moving forward.

Coincidentally, Cherry became a subscriber to Model Engineer magazine at about the same time that Bill Hughes was starting a series of articles on how to build the Allchin traction engine.

Plans for the Allchin engine could be purchased for 50 shillings (about $3 USD today), and model engineers around the world did so in large numbers. It became the most popular traction engine model of all time.

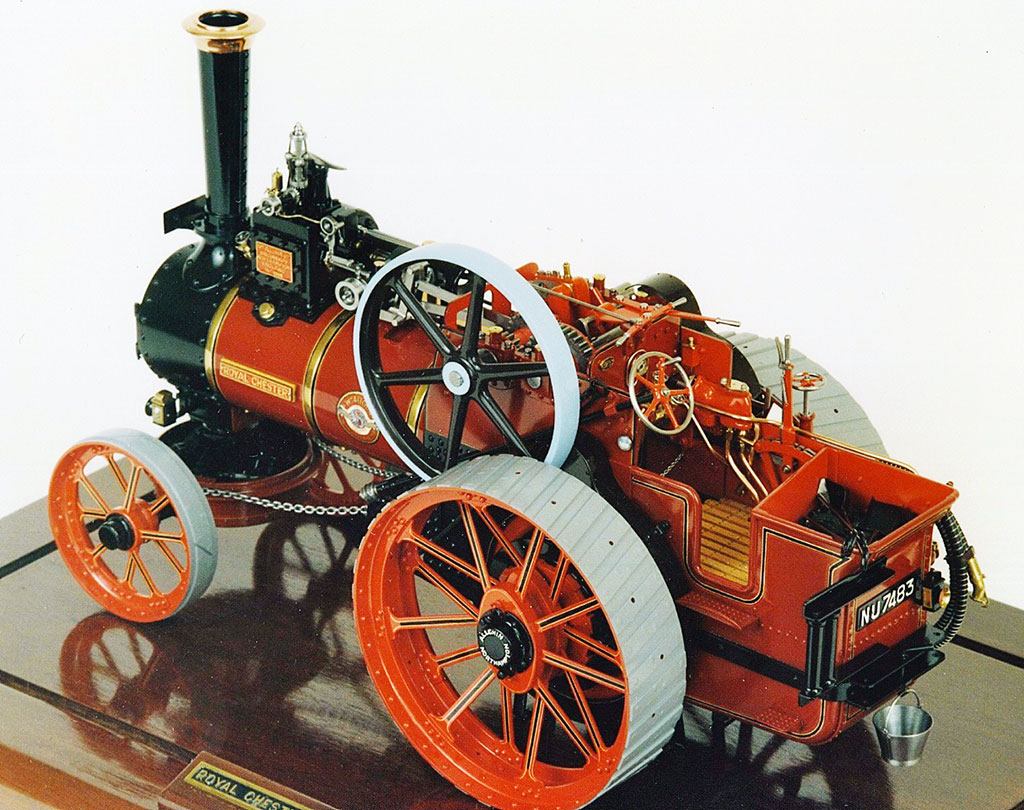

However, Cherry was concerned about the model’s large size. At the suggestion of her father, she decided to make the model at half the scale of the plans. She would build her traction engine at 1/16 scale, rather than 1/8. Following this decision, Cherry would build almost all of her future models at 1/16 scale. Unfortunately, there were no casting sets made for the Allchin at this scale, making her task all the more difficult. However, Cherry was able to locate the original Allchin Royal Chester No. 3251 at a location nearby.

Finding the original Allchin made it possible for Cherry to measure important parts, ensuring that her model was totally accurate. Ultimately, it took seven years to build, being completed in 1964.

The traction engine model was entered into the Model Engineer Exhibition, where it took a silver medal. Then, two years later the SMEE judges named the model runner-up for The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award—the highest honor in model engineering. Cherry’s career in model engineering was certainly off to a good start.

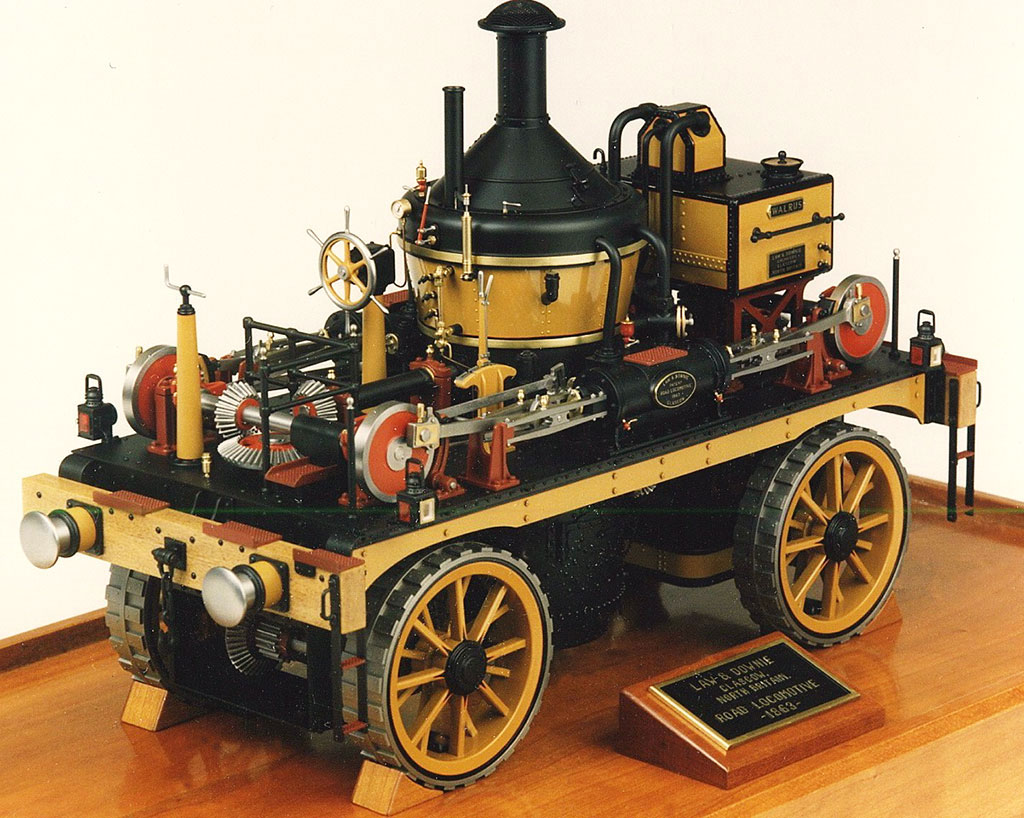

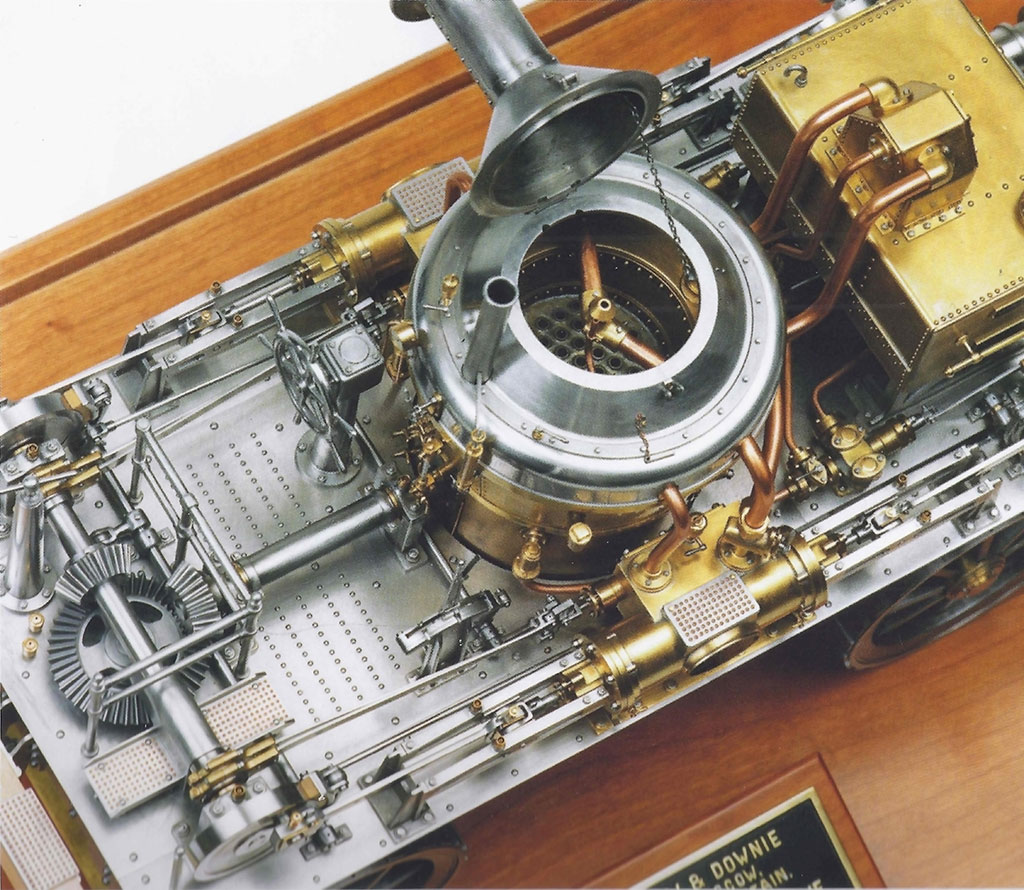

This 1/16 scale model of an 1863 Law & Downie road locomotive was built between 1986-1990 (approximately 6,500 hours). It weighs 16 lbs., and has the following dimensions: 14-1/4” x 6-3/8” x 9-3/8”. This model won a gold medal and the Bradbury Winter Memorial Trophy in 1992. It also won The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award for 1993.

Building Her Models

Starting out, Cherry’s first models were built from designs that existed as models, full-size examples, or at least had complete plans available. However, she became drawn to more unusual models, many of which were poorly documented, or had no surviving originals. After extensive research in old archives and magazines, Cherry would choose subjects with unusual designs. She sought out projects that were challenging to build, but could still be made to run. After settling on an engine, the process of researching, measuring, and making working drawings began.

Typically, Cherry would also make a simple study model of her engines to map out the basic forms, and to test certain functional aspects before starting on the final model. Each of Cherry’s models took about seven years to build, so it was critical to have all the kinks worked out in advance. The study models built prior to final construction definitely helped with that. Additionally, Cherry has never used CNC machinery during the building process. She prefers to do everything manually on traditional machine tools, including the occasional use of the Pittler lathe.

Accordingly, even a specialized process that might normally be farmed out—like photo etching tiny nameplates—was completed by Cherry in-house. Even though it took six months to learn this process, Cherry decided it was worth it to be able to control every aspect of her models. With few exceptions over the years, any part that was a casting on the full-size original would be machined from billet stock on the model.

Finally, the projects are tested, painted, and photographed. Most of Cherry’s models were shown in public exhibitions for several years, and then given away. None of them have ever been sold, and most reside in the archives of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in London. Earlier models were given to friends of family. The Institution of Mechanical Engineers website has photographed thirteen of Cherry’s models, and converted them into zoomable, rotatable 360° surround photos. They are individually linked near the bottom of this page.

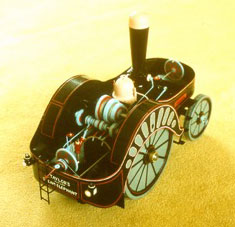

Cherry would first build a study model, like this one, to test out aspects of construction before starting on the final model. This is a James Taylor “Steam Elephant” traction engine.

Cherry’s Workshop

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Cherry’s machine shop includes tools from many eras—from a pre-WWII Gamages sensitive drilling machine to a Myford Connoisseur lathe. Her largest tool is a Myford milling machine, but she has an Emco and a Centec mill, too. Of course, she also still has her father’s old 1914 Pittler lathe, which was permanently set up for dividing.

Among her several other lathes are an IME watchmaker’s lathe, and a Cowells lathe for small work. For tasks on the really small end, Cherry has a row of tiny homemade BA open-ended wrenches, from 16BA increasing in gaps of 0.002”. There are also several custom-made dividing plates.

Cherry’s shop is very well organized, with wall racks for storing raw material, and divided matchboxes for the smallest parts and fasteners. Cherry also has a room with a large drafting table, and a mechanical drafting machine for making scale drawings. Painting and grinding are done in a separate room at the end of her garage.

The uncompromising craftsmanship exhibited in Cherry’s work is a result of her attitude. She never accepts anything less than perfection. For example, when a stud boss on her Blackburn engine turned out to be 1 mm too long, it was scrapped and remade. When she was reminded that no one would recognize the flaw, her reply was, “I would.”

Cherry Hill with two of her models gracing the cover of Model Engineer magazine in February, 1968. (Cover photo reproduced here with permission from My Time Media Ltd.)

Model Engineering Awards

The Joe Martin Foundation has selected model engineer Cherry Hill, of Malvern, Worcestershire, England as the 2017 Craftsman of the Year Award winner. Though she could not attend in person, her work was honored at theNorth American Model Engineering Society Expo in Southgate, MI. The award included a check for $2,000.00, an engraved gold medallion, an award certificate, and a commemorative book. Mrs. Hill generously asked that her award money be returned to the Joe Martin Foundation to be used for encouraging and rewarding craftsmanship through our awards program.

As further testament to Cherry Hill’s exceptional career, she won the following awards for excellence in model engineering with her ornate traction engines. Her earlier steam engine models also received awards in 1964 and 1968.

- The Sir Henry Royce Trophy for the Pursuit of Excellence (1989 and 1995).

-

MBE (Member of the British Empire) awarded by the Queen for services to model engineering (2000).

-

Elected Companion of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (2004).

-

Honorary member of the Society of Model and Experimental Engineers (2004).

-

Won nine different gold medals at the annual Model Engineer Exhibition in London.

- Won the Bradbury Winter Memorial Trophy eight times.

- Won the Aveling Barford Cup two times.

-

Won the Crebbin Memorial Trophy.

-

Won the Championship Cup three times. (Forerunner to the gold medal, with only one awarded each year.)

-

Won The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award nine times.

This model is unique because Cherry Hill made her own original design for the traction engine, then patented it and built it at 1/16 scale. It’s modeled after an 1862 Gilletts & Allatt traction engine. It was built between 1990-1998, then finished in 2001 (approximately 6,500 hours). The traction engine weighs 15.4 kg., and consists of over 7,800 separate components. It was awarded a gold medal, and the Bradbury Winter Memorial Trophy in 2002. It also won The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award for 2003.

Virtual Archive of Cherry Hill’s Engines

Thirteen of Cherry Hill’s models now virtually reside in the archives of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in London. The institution has posted an archive page featuring these models, with a 360° panoramic photo of each engine, which can be rotated or enlarged.

Here are the thirteen individual models made by Cherry Hill which can be seen in the archive link above:

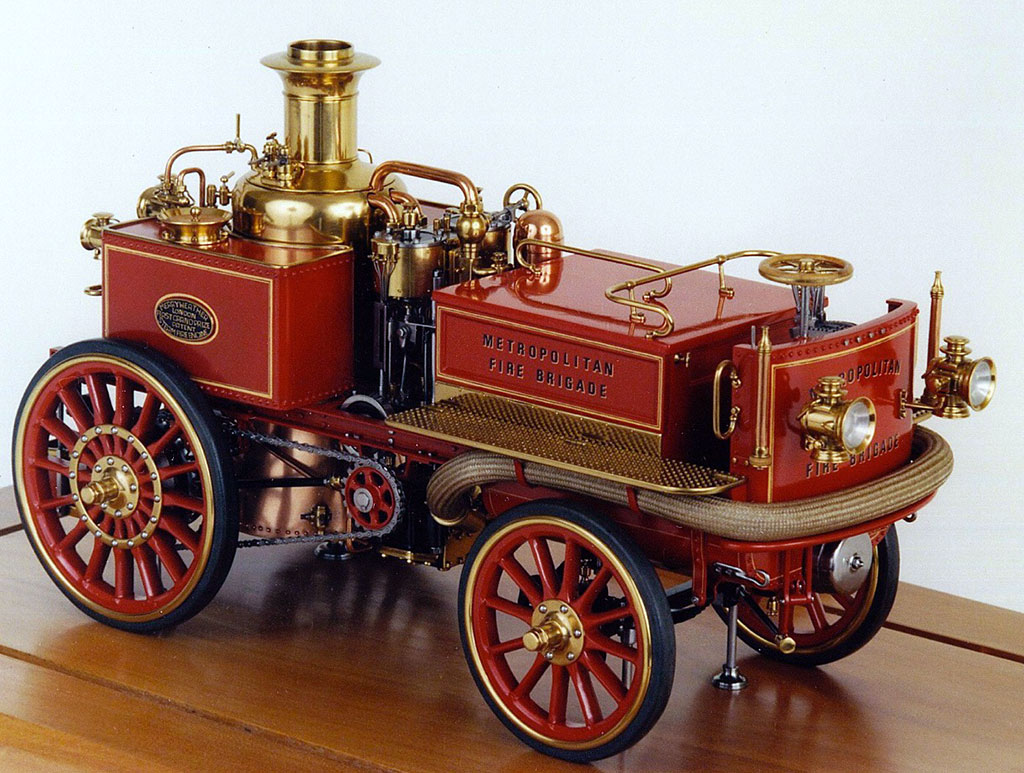

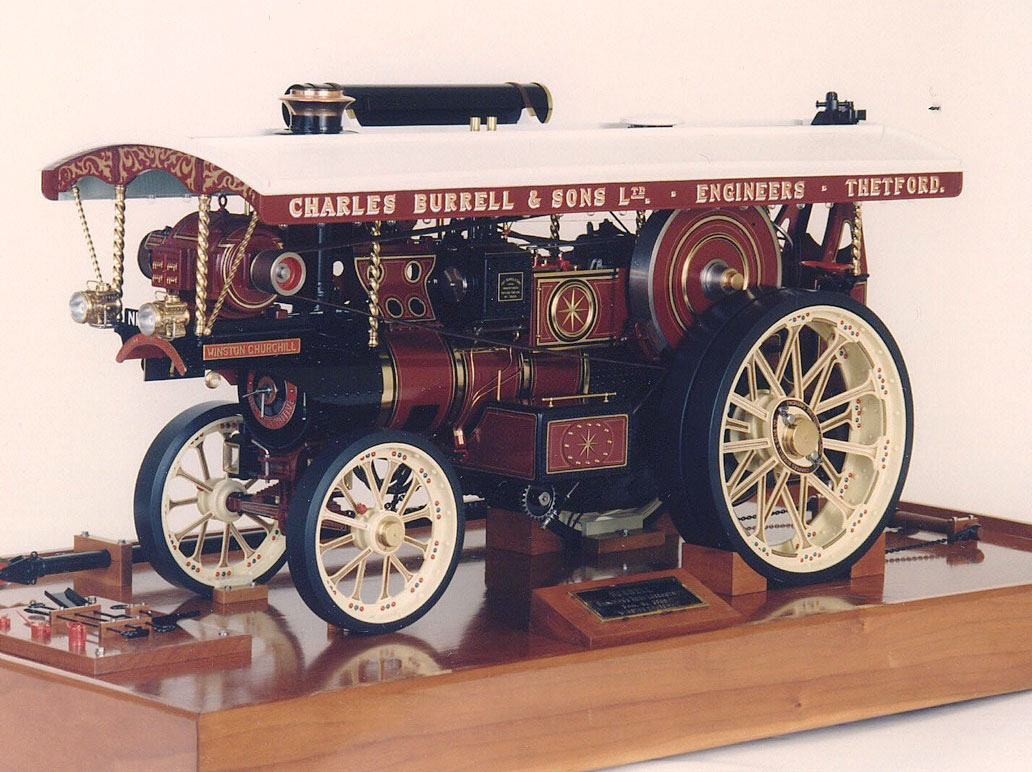

Gellerat steam road roller; Savage Centre engine; William Batho road roller; Merryweather fire engine; Law & Downie road locomotive; Aveling & Porter road roller; James Taylor “Steam Elephant” traction engine; Wallis & Steevens “Simplicity” road roller; Wallis & Steevens “Advance” traction engine; Andrew Barclay’s traction engine, and boring and winding engine; Gilletts & Allatt traction engine; Isaac & Robert Blackburn agricultural engine; and a Robert Blackburn agricultural engine.

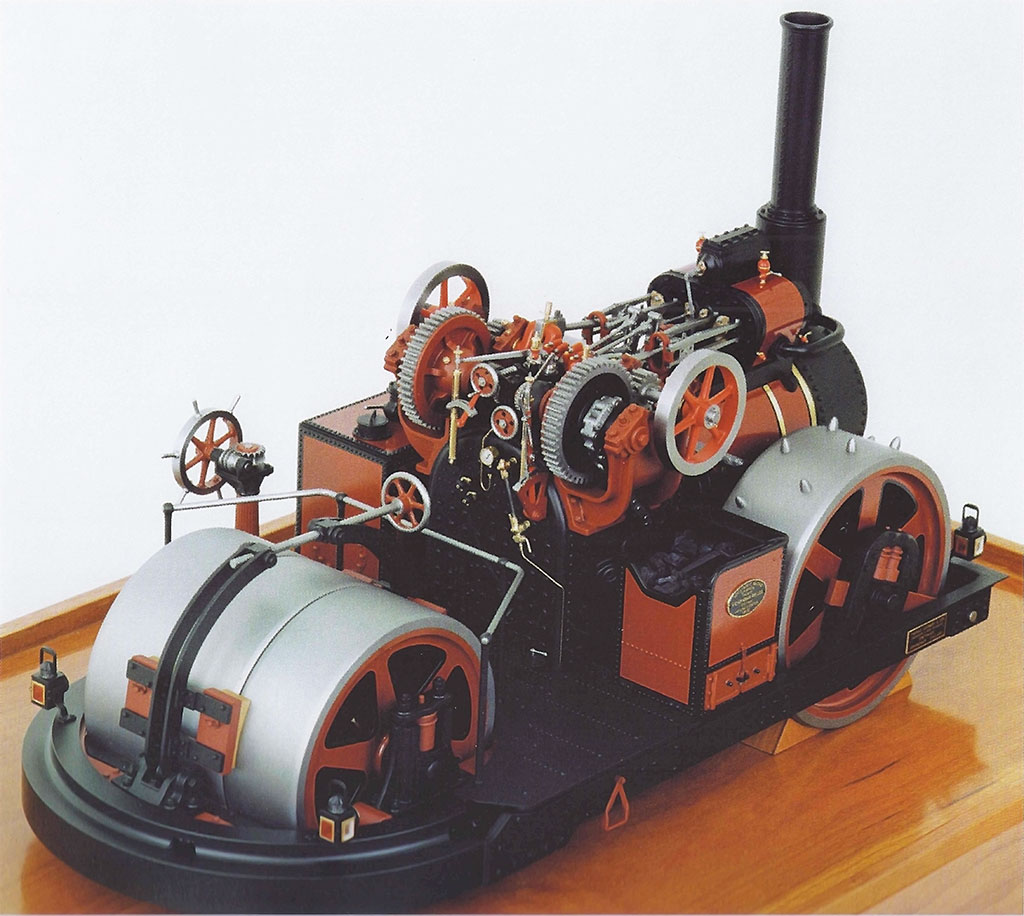

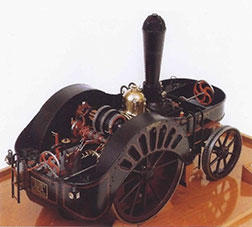

This 1/16 scale model of a 1931 Aveling & Porter road roller was also built between 1966-1969 (approximately 2,500 hours). The model weighs 16 kg., and it has the following dimensions: 15” x 5-1/2” x 7-7/8”. It was awarded the Championship Cup (predecessor to the gold medal), and the Crebbin Memorial Trophy in 1970. This model also won The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award for 1971.

Cherry Hill’s models can be seen in person at the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in London, England. Though open to the public, it is recommended that visitors call in for an appointment to see the models in the archives section. David Carpenter, author of the definitive book on Cherry Hill’s work and former editor of Model Engineer magazine, also produces an online magazine on model engineering where you can see more of Cherry’s projects. We regret to inform that Cherry Hill passed away on December 4, 2024. We thank her for her dedication to exceptional miniature craftsmanship.

View more photos of Cherry Hill’s award-winning model engineering.