Artist in Machined Metal

Introduction

When craftsmen are honored by the Joe Martin Foundation, their inclusion in the museum is an acknowledgement that their projects go beyond mere metalworking. In most cases, the pieces made by these craftsmen are truly works of art. William Dubin honors that tradition in a very direct way, by taking elements of model engineering and turning them into kinetic sculptures—which are displayed in an art gallery setting. His pieces show that the elements and movement of vintage steam engines are more than just a collection of metal parts.

The combination of these functional parts, their precisely machined surfaces, their interrelated movements, and the aged patina of their exterior, become more than just an engine. They become functional works of art. Mr. Dubin started his career as a sculptor working with wood. However, one day he saw an issue of Model Engineering magazine, and realized what his work was missing—precision. William was impressed by the beauty and precision of the steam engines he saw, and felt that this precision was what he wanted to capture in his own work.

Following this instinct, William bought a metal lathe. With the help of a fellow artist and metalworker in the studio where he worked, William set it up and began to make metal parts. He had no formal training in machining, nor any experience, and went about learning the process on his own.

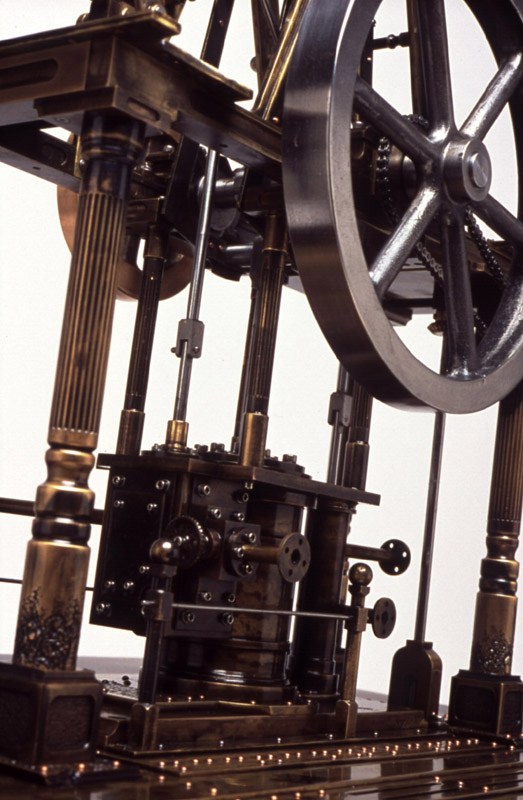

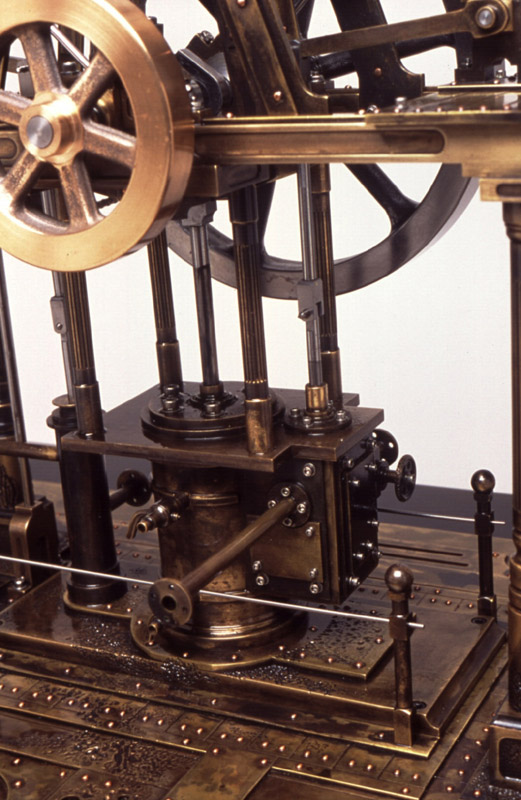

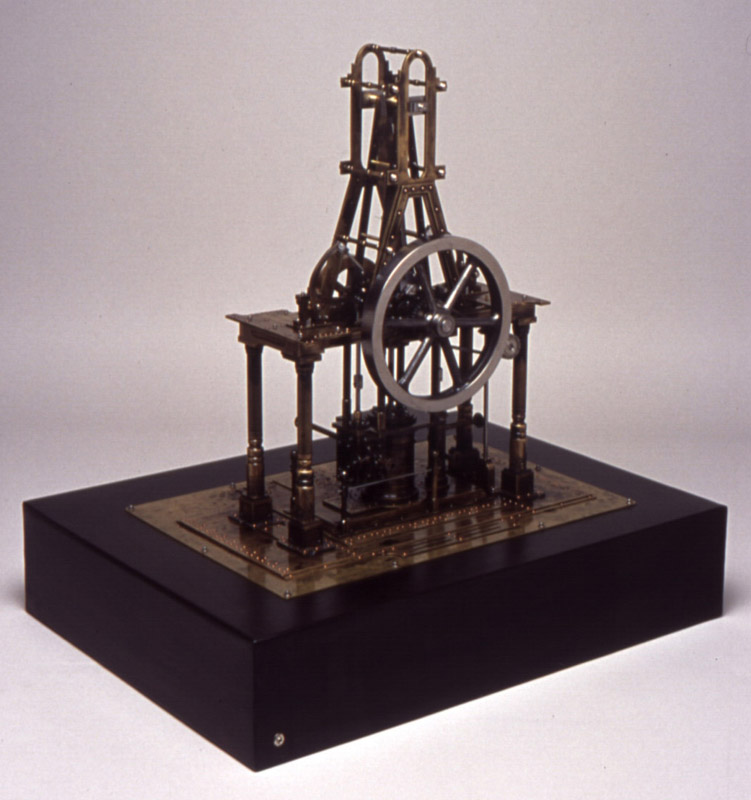

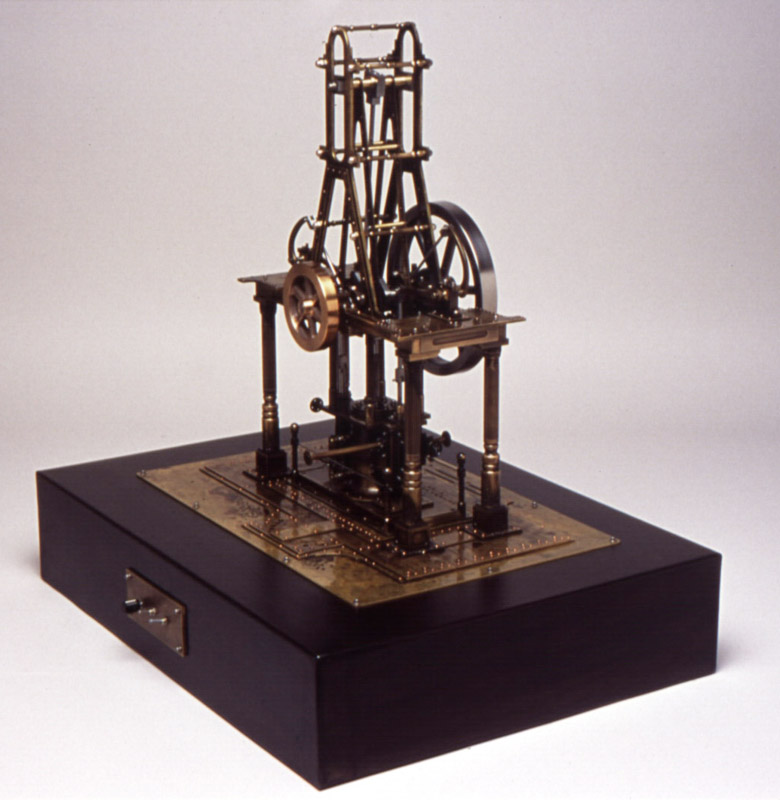

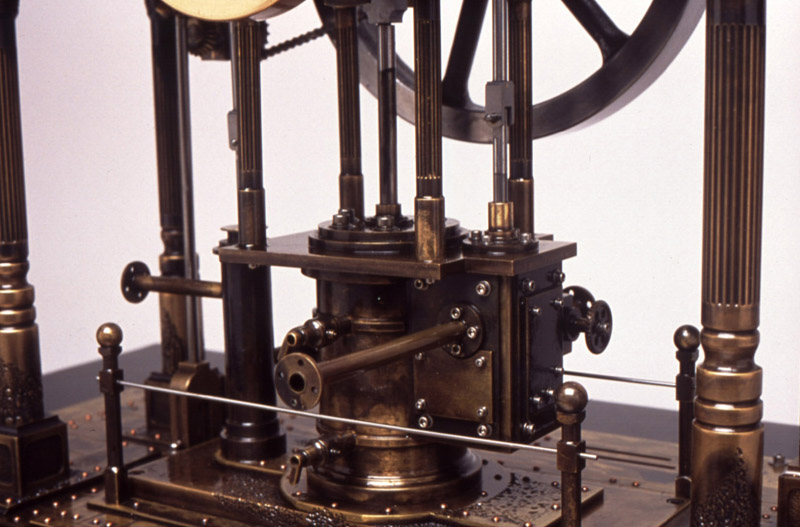

This photo shows Dubin’s steam engine sculpture, Jenny. The engine mechanism can be seen on the lower level.

In the early stages, William’s first pieces were fairly organic. He then produced a piece that was very much like a steam engine. His next work included elements of movement with belt driven shafts, and he knew he was on track for what he wanted to do. But why not just build models of steam engines? Why turn them into art? Mr. Dubin explains the difference between his work and conventional model engineering:

“This question goes to the heart of what I do. I am a sculptor. When I construct something, it is specifically to make “art.” While my sculptures have a great deal in common with model engineering, it is with the process of model engineering, rather than the end results. My sculptures are a way for me to express my ideas and reactions to the world I live in, and to my experience of that world. Each piece I construct constantly evolves, as my reaction to what I’ve just built alters my ideas of what I’d like the final piece to look like. This is very different from model engineering, where the adherence to a specific prototype dictates most, if not all of the final appearance of the model. This is not to say that model engineering isn’t artistic, quite the contrary. I continually see models which are amazingly artistic; however, the intent of the model engineer is to closely resemble a prototype—not to create art. It is in this intent that the two differ.

This postulates two levels of engineering: the first, an aesthetic based engineering; the second, one in which the engineering does not go beyond function. In the first example, the finished piece compliments the prototype, but goes past the visual impact the prototype would make. This quality is elusive, but it exists, and can be easily seen in the best work of model engineering and the fine arts.

What happens in these pieces is a meeting of creativity, craftsmanship, and a highly evolved personal aesthetic of beauty—all combining to produce a category unique to both model engineering and sculpture.”

—William Dubin

Notes on Building the Jenny

By William Dubin

Jenny evolved from a sketch I had seen in Model Engineer, the Centennial Celebration Collection, #7 Stationary Steam Engines. The original sketch and letter were from J.A. Blythe (of Glasgow), and dated November 18, 1937. These appear on page 84 of the magazine. The sketch and description (from memory) are of the single cylinder steeple engine from the paddle steamer Glencoe, built in 1846. The sketch (a side and end view) offered the most unusual configuration I had seen to date for a steam engine, and I knew I needed to build a sculpture based on the prototype.

My practice is to start with the basic mechanism, which I pretty much reproduce intact, and then to embellish the environment in which I locate it. In Jenny’s case, as there was not going to be a ship deck involved, I put her entablature on four stout columns, with the cylinder mounted underneath. Once the basic configuration was worked out, the parts were made in the traditional fashion.

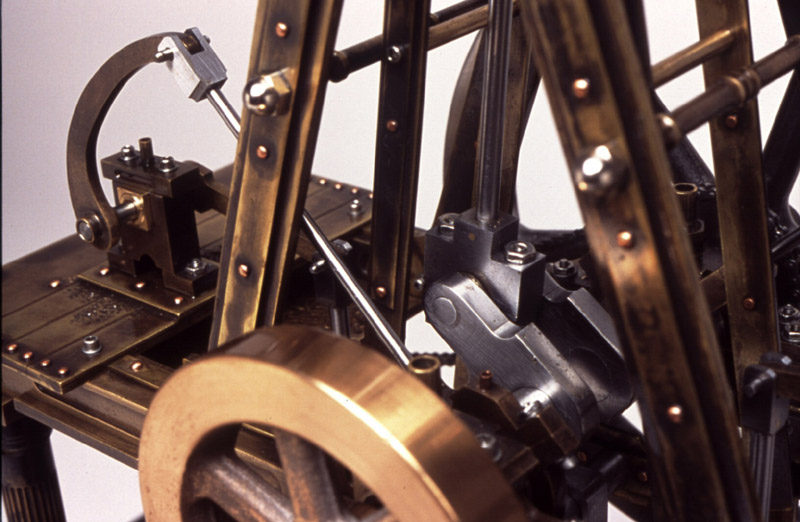

Recently, I have been using tiny carbide ball-end bits, in a Foredom shaft, to create various textures by carving directly into the surfaces of the metal. With Jenny, I took this further than I had before. The result was that the sculptural aspects have asserted themselves, as opposed to the mechanical and the machined, in a very powerful way.

The biggest problem I encountered in building Jenny was designing her drive unit. I used a shaft with two sets of bevel gears, running from the motor mounted in her base up to a sprocket, and chain connected to her crankshaft. Jenny has a decidedly syncopated beat, both in her motion and her sound. The motion has a tiny visual stall at both TDC and BDC, and the sound she makes has a jazz beat that I’ve come to enjoy.

Jenny operates through an inverted “V” shaped yoke. The bottom of the yoke connects to the piston rod, and the top to the crosshead and side blocks. The whole rides between the two upright pieces that form the “steeple.” The crosshead is linked to the connecting rod, with the small end located between the twin frames of the yoke. The big end is attached to the crankshaft, which is located in the center of the entablature. There are two eccentrics located on either side of the crank journals. These activate the cylinder valve and the boiler feed pump.

—William Dubin

Mr. Dubin’s work has been displayed in art galleries, and sold as artistic pieces. An excellent article on Mr. Dubin’s work, including a cover photo, appeared in the January 10-23, 2003 (Vol. 190, No. 4186) edition of Model Engineer magazine. This is particularly appropriate, since it was an issue of that magazine which inspired Mr. Dubin to proceed with his art in the first place.

You may see more of Mr. Dubin’s work in his website gallery. Additionally, view more photos of William’s artful model engineering sculptures.