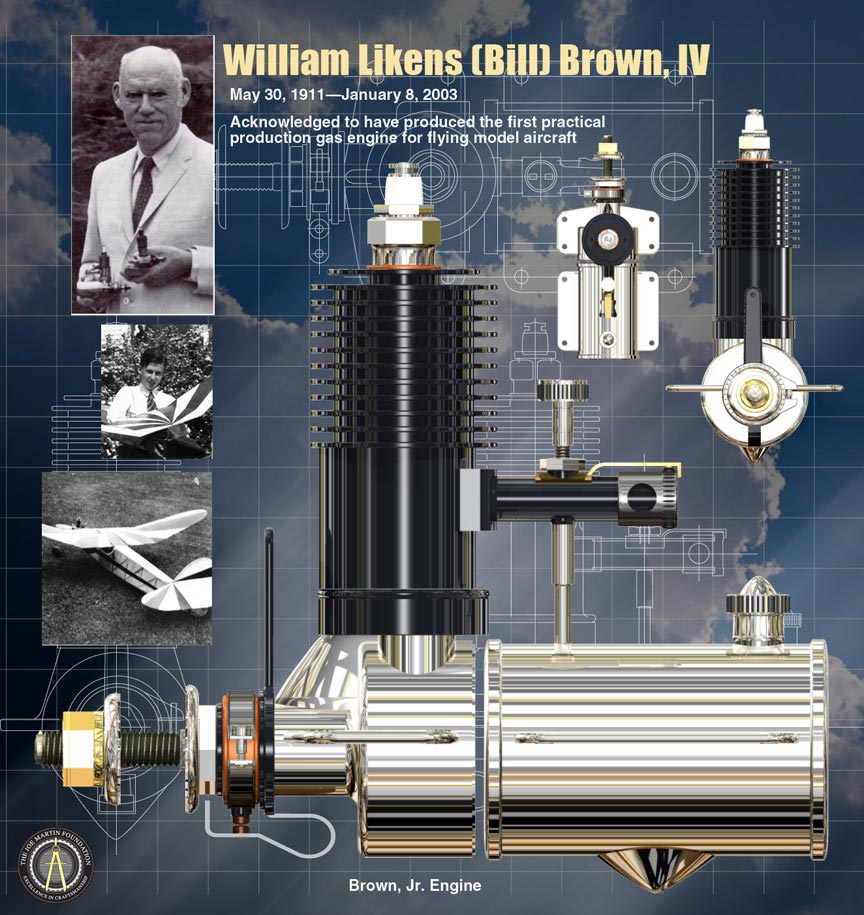

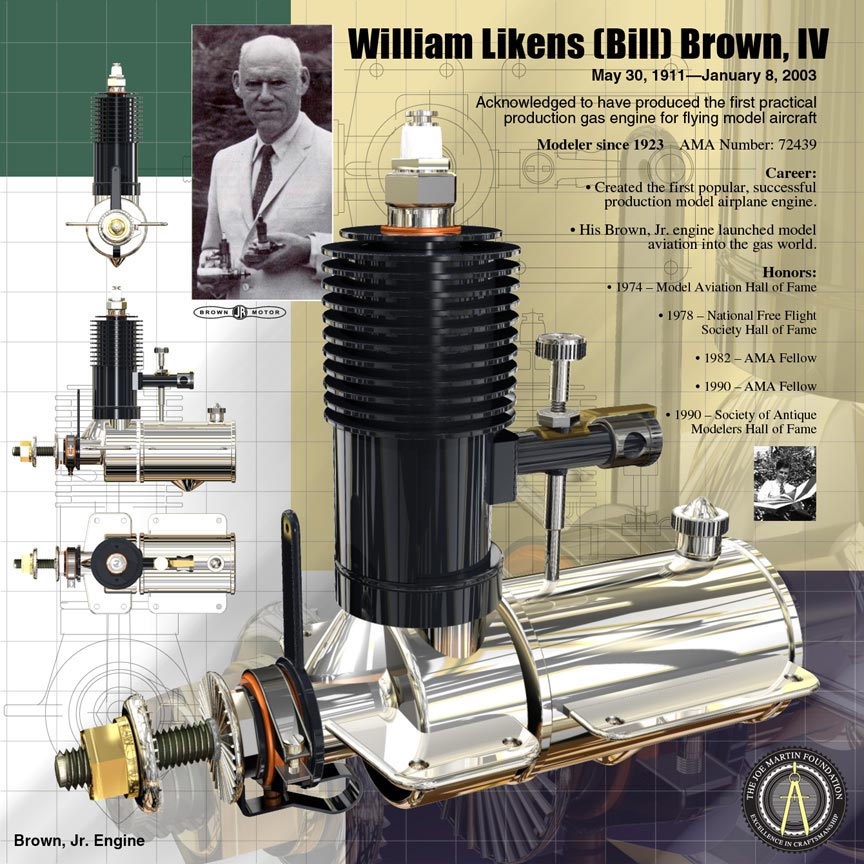

May 30, 1911—January 8, 2003

Acknowledged for Producing the First Practical Production Gas Engine for Flying Model Aircraft

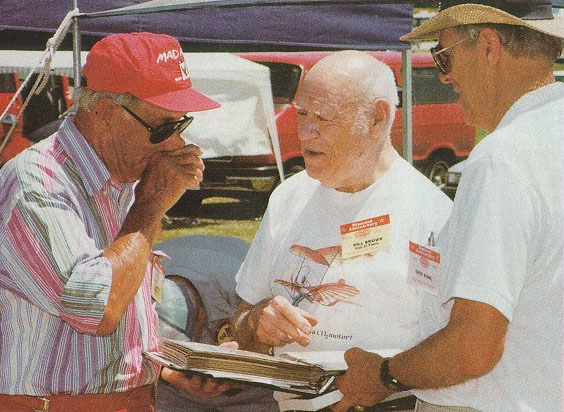

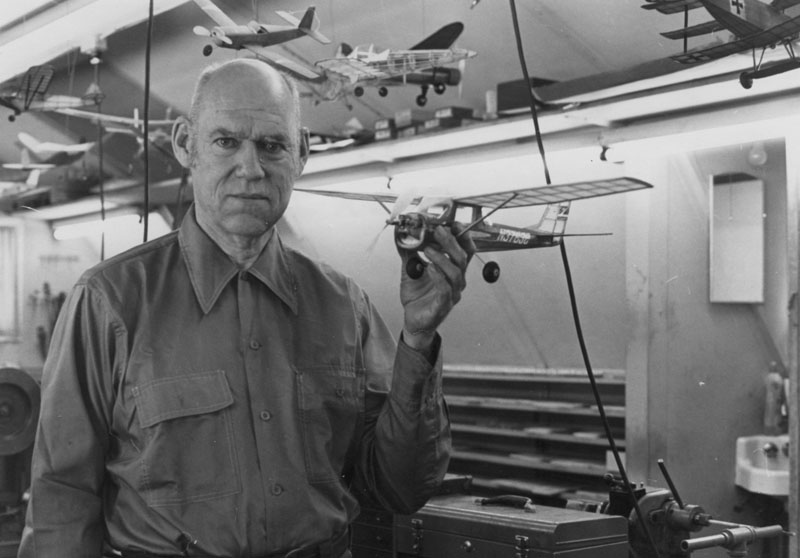

Mr. William “Bill” Brown. This photo, along with others on this page, were provided courtesy of the State College Radio Control Club. Photo from Model Aviation magazine, 1969.

Intro

Model airplane engines were first developed as early as 1909. However, these were experimental engines that were made one at a time. They worked to varying degrees of success. The “Baby” engine of 1911 was produced in very small quantities, but still couldn’t be called a production engine. In this regard, the engine designed by Bill Brown was the first to be built in significant numbers, and sold to the general public—revolutionizing competitive model airplane flying.

In the 1930’s, during the Great Depression, these early engines were being developed. Unfortunately, not many photos were taken. Many of these engines were being built on a shoestring budget, and the builders were more interested in getting them built than documenting their progress. As a result, the history of early model engine builders is not well documented visually.

Fortunately, a great deal of research was done by Mr. Evan Towne to provide an account of Bill Brown’s life work. In fact, Mr. Towne worked with Brown himself to come up with an authoritative profile of his early days, and the invention of these groundbreaking engines. These engines served as the foundation for the model aircraft engine industry, and Mr. Brown’s contributions deserve recognition as such.

We thank the Academy of Model Aeronautics for permitting us to use Mr. Towne’s biographical information and photos here. We would also like to thank Tim Dannels, of The Model Engine Builder’s Journal, for contributing photos of Bill’s rare early IC and CO2 engines.

The following biography of Bill Brown is provided courtesy of the Academy of Model Aeronautics’ History Project. You may access the complete biography directly from the AMA archives.

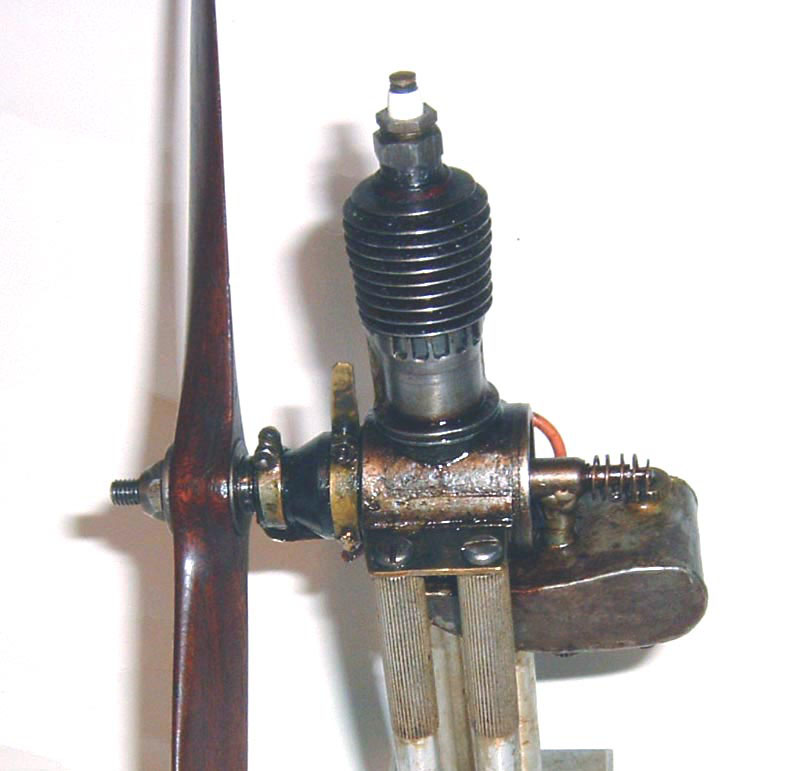

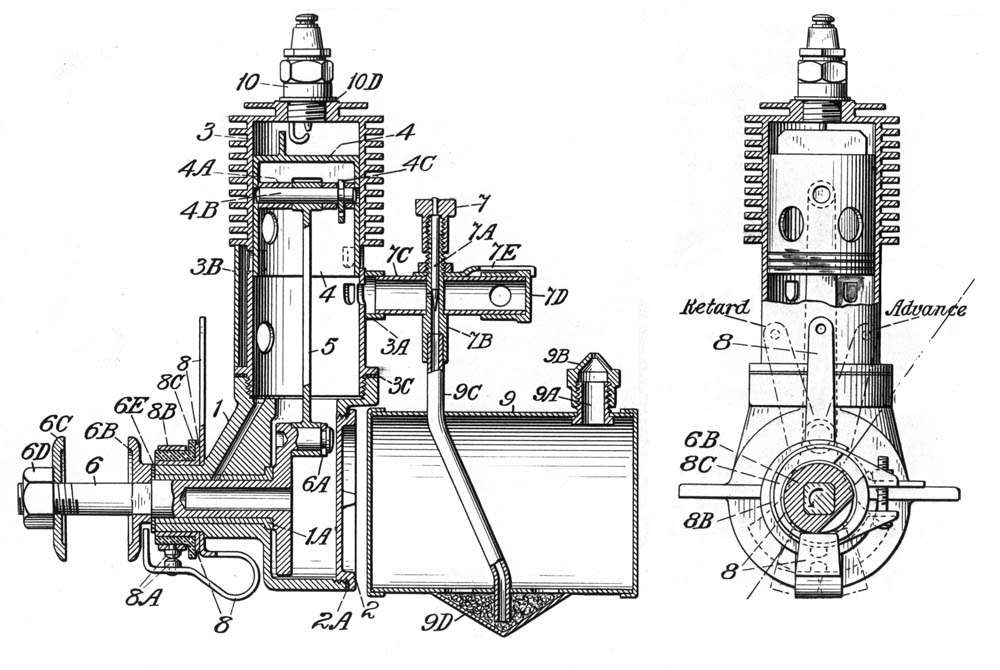

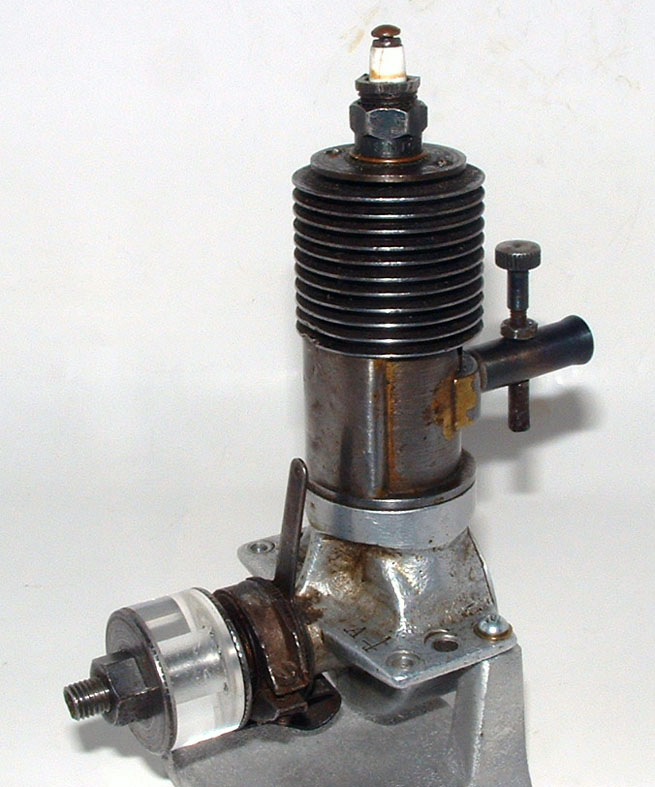

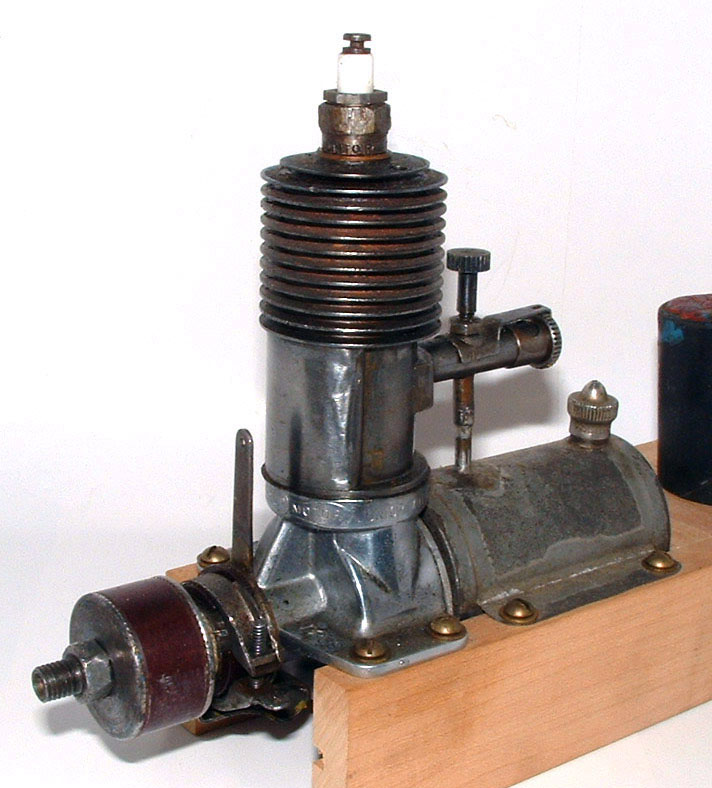

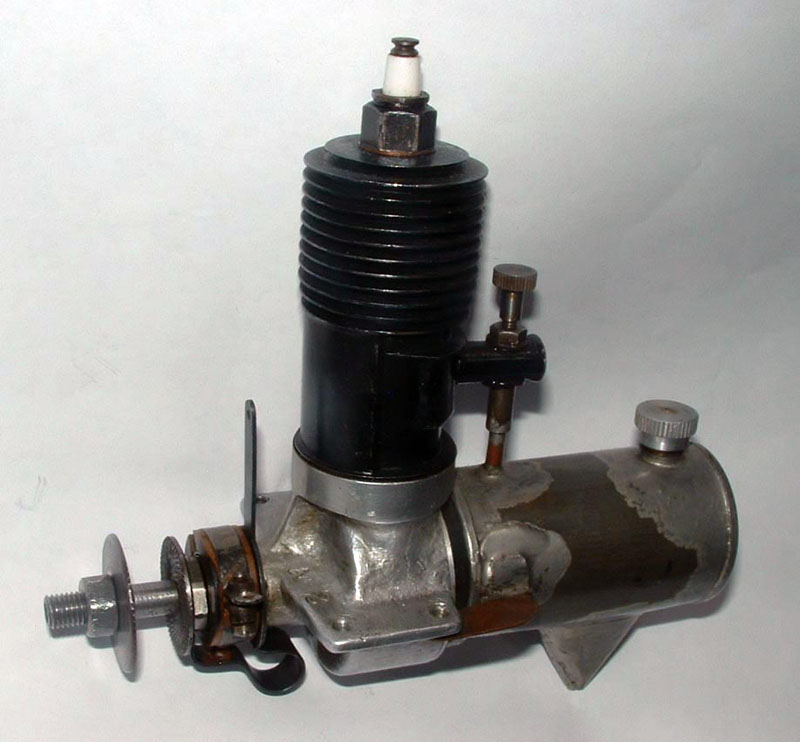

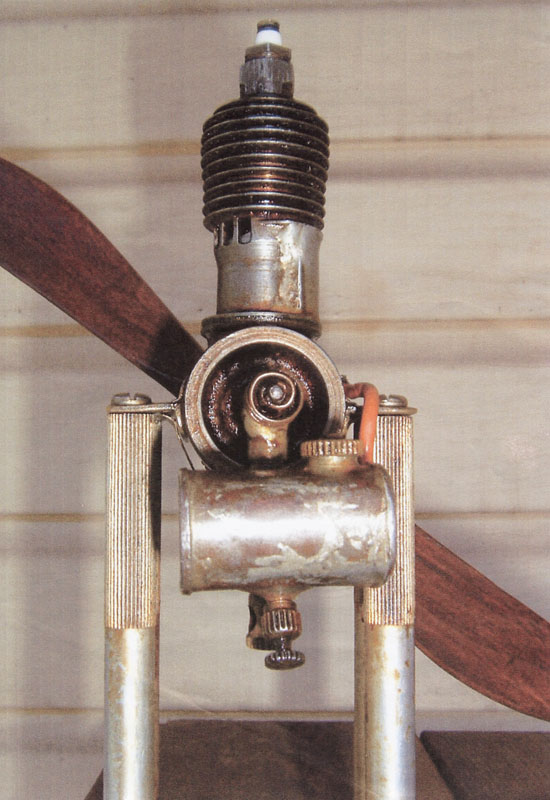

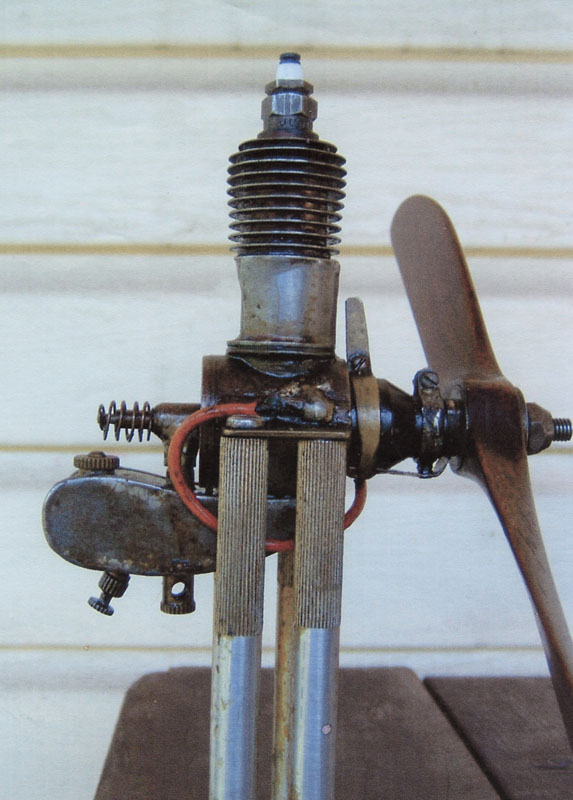

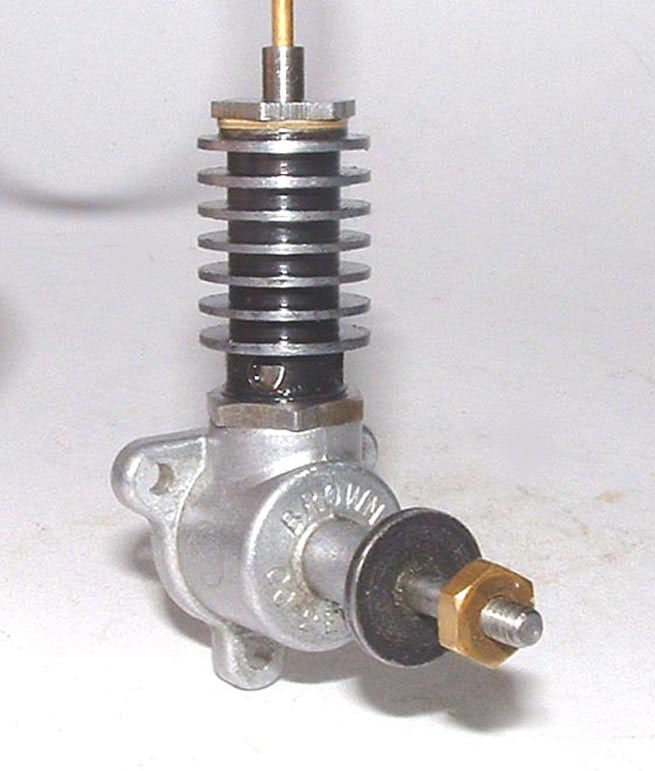

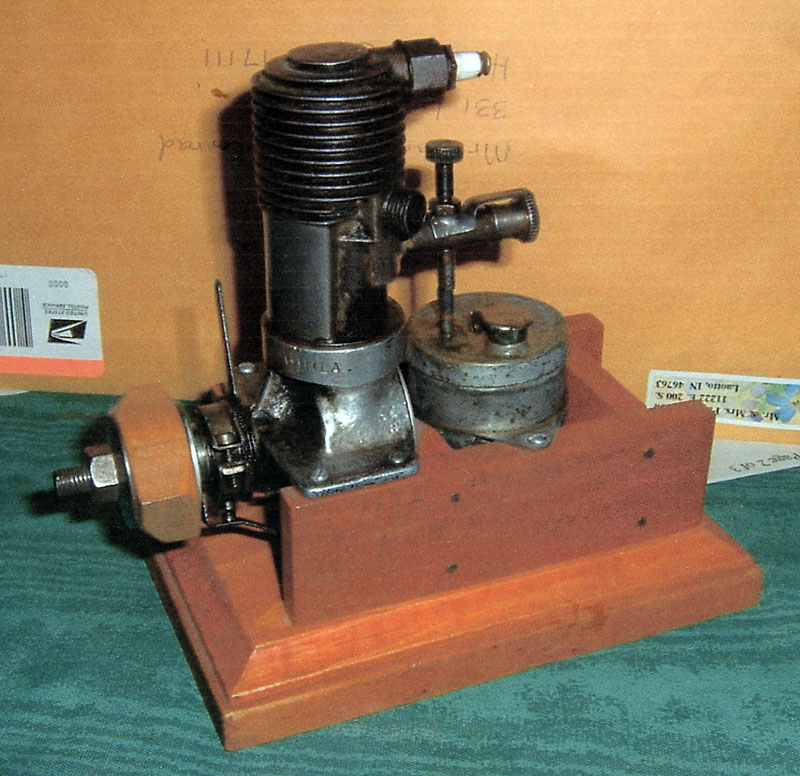

Here are two views of what is generally called the “High School” Brown engine. It was the first operating model engine that Bill built in his dad’s home shop, while still in high school. Photo by Jack Conrad.

Bill’s father didn’t think much of the High school engine at the time, but it’s now considered one of the most significant engines in modeling history. This is because the design truly introduced gas powered flight to smaller model aircraft—with an engine that could be purchased by the public. Photo by Jack Conrad.

Brief Career Summary—Bill Brown IV

Mr. Bill Brown began his modeling career in 1923. Brown created the first popular, successful production model airplane engine. His Brown Jr. engine launched model aviation into the gas world. Over the course of his career, he garnered these honors:

-1974: Model Aviation Hall of Fame

-1978: National Free Flight Society Hall of Fame

-1982: AMA Fellow

-1990: AMA Fellow

-1990: Society of Antique Modelers Hall of Fame

Mr. Model Engine—Bill Brown

Biography by Evan T. Towne.

Bill was born on May 30, 1911 to good upper middle class parents, as his father was a respected mechanical engineer. Bill had a brother and a sister. As the first son in the family, he became the fourth generation to have the name William Lykens Brown. (Later, Bill’s son became the fifth—but he is a bachelor!) Bill’s father (the third) made sure that Bill got a good understanding of mechanics. At the age of three, Bill’s dad would show a picture of a locomotive or machine and point to a part. Bill would tell the audience what it was, and sometimes what it would do.

Now, Bill’s dad was a proud man, who provided for his family of five, plus his own mother. Naturally, he had an excellent wood shop and machine shop on the first floor. The fact that it was not in the basement reveals how important it was to him. Even though he smoked a pipe, he told Bill never to smoke, and never to drink alcohol. Bill thought this good advice, and took it.

In first grade, one of Bill’s classmates had a rubber powered model airplane. Bill was fascinated. Later, his dad bought him a book, Model Flying Machines, by Morgan, 1913. Bill still had the book at the time of this writing. At age seven, Bill tried to make his first model from the book. He used a broomstick for the body, and cardboard for the wings—but it didn’t fly.

Years later, he made another one from the same plan. This time it did fly. He and his neighborhood flying buddy, Maxwell Bassett, built and flew many rubber-powered models, some that Maxwell had designed. Bill lived on 10th Street in Philadelphia, and Maxwell lived on 11th Street.

When Bill was 12, he made his first model that really did fly—a Cecil Paoli twin boom pusher, from plans purchased from Ideal Model Aeroplanes and Supplies. In the 1920s, he said he worked all summer, building kites and selling them to the neighbor kids, so he could buy a three foot Jenny for $8 from Ideal. Later, he had a dream that his model had an authentic tiny working engine in it, just like the original Jenny. This started him thinking about a model airplane engine.

His dad had a twin cylinder outboard motor that fascinated Bill. He figured out how it worked, and eventually used it as a basis for his model engine. This is where he got the poppet valve intake idea. In 1926, he started drawing up sketches for his model engine. For several years, he kept thinking and drawing up his ideas.

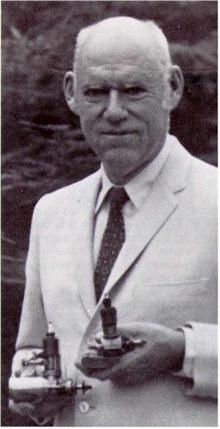

Bill Brown holding one of his first handmade engines (right) from 1930, and one of the Brown Juniors (left) from the first production run. This photo is purported to be from the AMA news section of American Aircraft Modeler magazine, February, 1975. The AMA started producing its own magazine, Model Aviation, shortly thereafter in July, 1975. Photo courtesy of Potomac Aviation Publications, Inc. 1975.

When the Great Depression came along, Bill’s father lost his job, as did many others. He sold his vacation home and barely survived, compared to what he was used to. Somehow, he was able to keep his home and his machine shop. He had several small jobs, including selling railroad spikes.

In high school, Bill finally started fabricating parts for his engine while just “monkeying around.” When his dad saw him working on it, he told Bill that it was a waste of time, and that Bill should be studying instead. All the work on the engine was done in his dad’s machine shop, including the spark plug. The spark plug was made just like big aircraft plugs, with a built-up mica insulator. The spring tension on the poppet valve was very critical, but he finally got it right.

When it was finally running, and his dad found out about it, Bill said, “His exact words were a sarcastic ‘Now what does that prove?’” Bill did not realize what a strain his father was under, having been fired from his job through no fault of his own. Bill was deeply hurt at the time, but he came to understand that whether he wanted to or not, he had taken some of the position of leadership away from his father—at least in this area. Bill said that as much as he loved and respected his dad, their relationship was never the same again. (This was around December of 1930.)

Bill carried the parts of his engine around in a briefcase. One day in shop class, he showed it to some students who then asked him to run it—so he did. The instructor investigated the noise, and was flabbergasted when Bill admitted to having built it.

Maxwell Bassett was as innovative at designing models as Bill was in making engines. As soon as Bill had an engine ready, Maxwell had the plane designed and built for it. Fortunately, Bill had located an excellent supply of balsa planks and smaller scraps at one of the lumberyards. Bill and Maxwell took their new plane out on 10th Street and fired it up. It struggled into the air, but never got over four feet off the ground. Bill decided that it needed more power—and he already had some new ideas for the next engine.

So he started all over again, but this time he doubled the size and made the first Brown Model A. They put the new engine in the same plane, and again took it to the street. This time it leaped off the ground, did a couple of loops, went over a house, and landed in some bushes. Maxwell experimented and practiced all summer long, and started getting better results with the model design.

On Bill’s 20th birthday, Saturday May 30, 1931, the Philadelphia newspaper, The Evening Bulletin, ran a picture of Bill and his plane—with a close-up of the engine held in his hand. There was also a working drawing of “How to Build a Midget Gasoline Motor.” The three-column story was titled, “Builds Tiny Motor Monkeying Around,” and was written by Bill’s friend, Victor R. Fritz.

Even though Bill’s original engine had a built-up steel crankcase, an aluminum casting was offered to those interested in building the engine. Right next to the column was a scripture verse, “Whatsoever things are true…. honest, … just, …pure,… lovely …of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things” (Philippians 4:8). Bill took this as a go-ahead from God to develop his model engine.

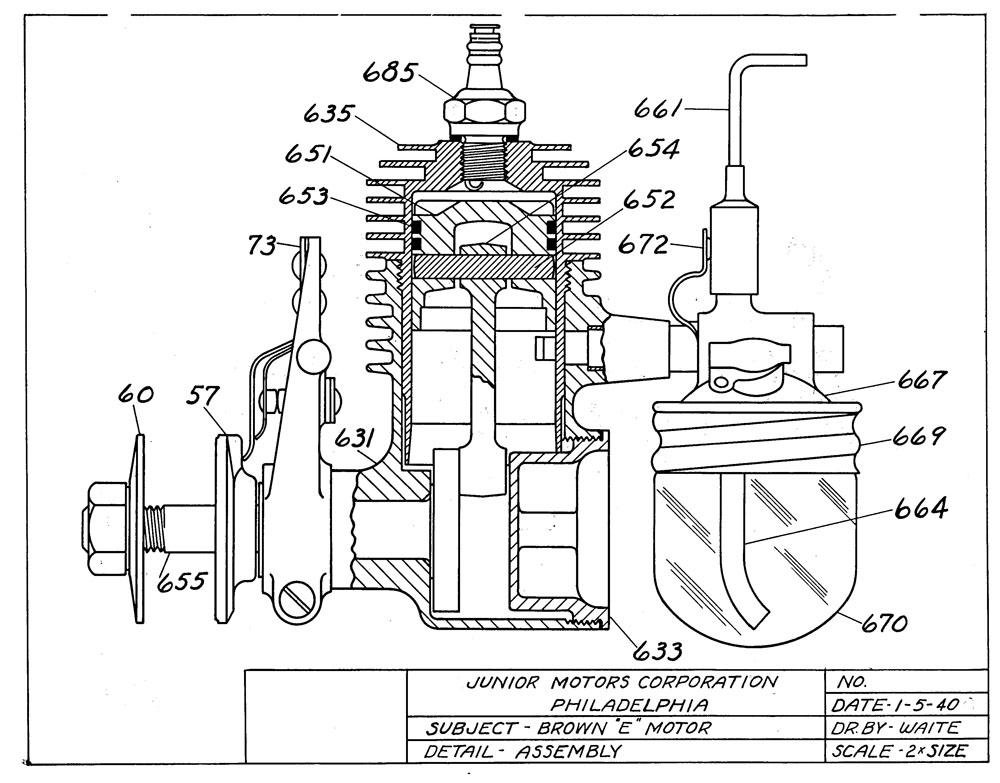

Because of all the publicity Bill had gotten over his first small engine, his father decided to help Bill design his next engine. As Bill wanted more power, his dad designed the Brown Midget Motor to be a .451 cubic inch engine. During the summer of 1931, they built three in their shop, but none of them ran! Nine years later, this design became the basis for the new small engine for Junior Motors Incorporated (the Brownie model E).

Bill learned a great deal in the process, as this was his first experience with formal machine design, ink tracings, blueprints, patterns, castings, and further experience in machining. Plus, he was learning all this from his father. At school, they were drawing simple bushings, projections, and other basic things. (Bill never thought to take his engine drawings to show his teacher.) Sixty-three years later, these very tracings were unexpectedly returned to Bill by someone that had worked at Brown Junior Motors!

In 1932, the ruling authorities at the National Championships (Nats) had only one classification—powered models. In order to encourage contestants to be innovative, any power source could be used, but almost all contestants used rubber power. A very few used compressed air, with limited results. Maxwell took their gas model to the Nationals at Atlantic City and entered it. His model that he named Miss Philadelphia came in fourth. To some perceptive people, this was the “end of innocence,” as the gas model had arrived! To others, though, including the rule makers, this was just a passing fancy that would create little further interest.

This trophy for the 1934 record flight was awarded to Bill Brown. Maxwell Bassett received a similar one. Because of their overwhelming success sweeping all three divisions, the rule makers finally realized the game had changed, and added a “gasoline engine” division in 1934. The plaque attached to this trophy reads, “P.M.A.A. Achievement Award to Wm. L. Brown Jr., for Gasoline Powered Flight, 2 Hrs. 35 Min., 35-1/2 Sec., May 28, 1934.” The trophy was awarded for the flight of Max Bassett’s aircraft powered by a Brown Jr. 60 engine. It flew from Camden, NJ to Delaware—reaching 8000 feet in altitude. It was followed by a full-size Fairchild aircraft, which landed near where the model went down. The crew retrieved it, and returned it to New Jersey. The trophy is now owned by Jim Conrad, who submitted this photo.

The next year, Bill and Maxwell both showed up at New York’s Roosevelt Field for the 1933 Nationals with several different models and engines. They won first place in all three powered contests: Stick model Mulvihill with a time of 14 minutes 55 seconds, Cabin model Stout with 22:22, and Moffeft International with 28:18. There was also one other gas model entered, the K.G.

Charlie Grant, the editor of Model Airplane News (and a real model engine enthusiast), and Joe Kovel entered a big eight foot model into the contest. It was named for them, and had a big aluminum engine. Grant designed the model and Kovel built it. Unfortunately, it was not finished until the day before the contest.

On the day of the contest, they worked and worked to start the engine, but only got a few coughs from it. Bill even went over and tried to get it going, but had no luck! Bill had handmade 12 engines to sell at the competition for $15 each. Charles Grant got the last one that Bill made in his dad’s machine shop. The judges finally woke up and made new rules for gas models.

The two Philadelphia boys got worldwide publicity. The model magazines wrote all kinds of stories, some with bad inaccuracies. People all over the world wanted to try gas models, which resulted in a ready market for model engines. Of course, he could not keep up with demand, so Bill’s dad found an excellent machinist and innovator, Walter Hurlman, who ran a tool and die, and experimental machine shop. Bill said he was the best in the business! Together they made about 50 more Brown Model A’s (now called A-60 by the engine collectors).

Even though it was the middle of the Great Depression, and even if you did not have a job to go to, you could still make models. If you wanted an engine badly enough, there were a few available from Bill, then others. With so many people wanting engines, Bill’s dad had been scraping the bottom of the barrel long enough. He swallowed his pride, took Bill’s engine (which now looked much better to him than before), and with a friend who knew some high finance people, convinced them to start a model engine company.

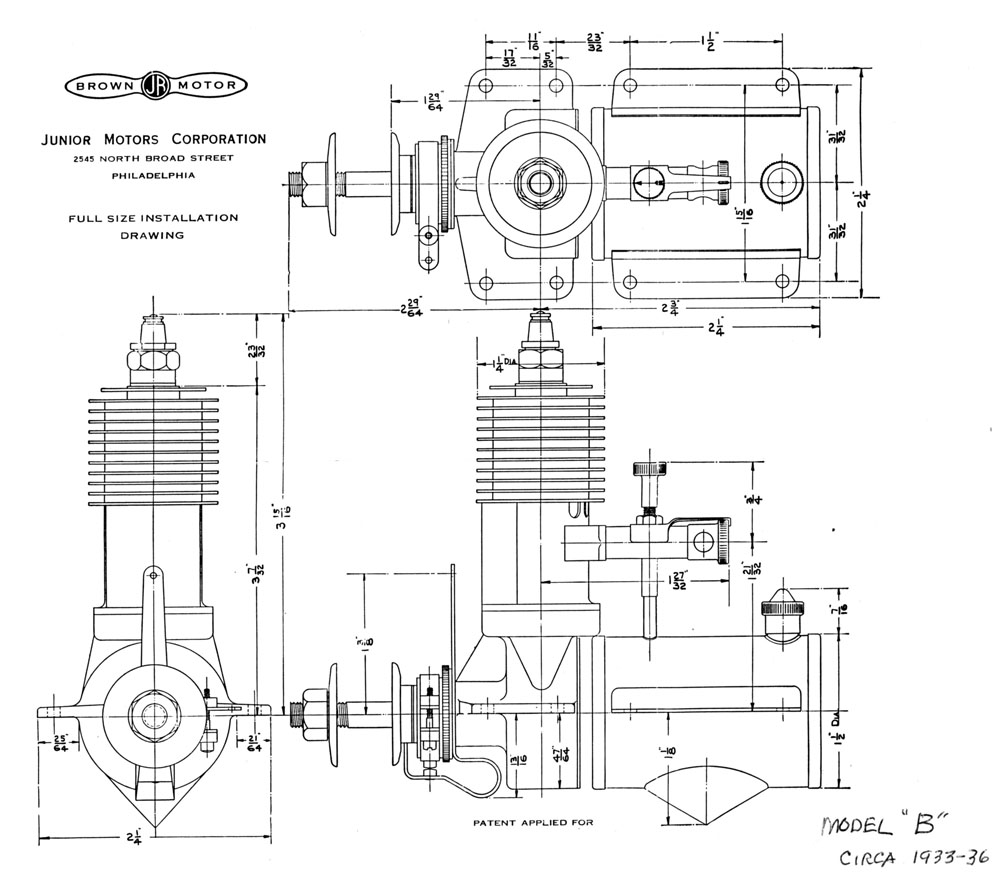

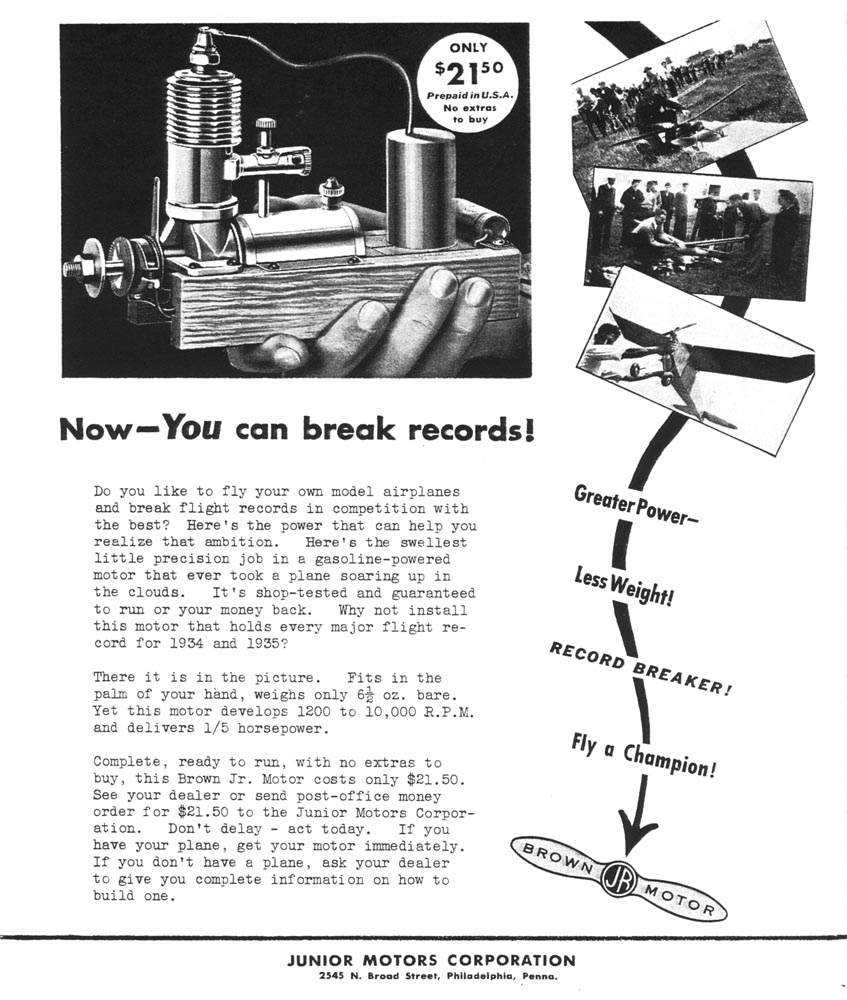

The first mass produced model engine was the Brown “B,” produced by Junior Motors Corp in Philadelphia, PA. For years, this engine won many flying contests, and held a number of records. A failure to acknowledge the need for a larger selection of engine sizes—a need anticipated by Bill Brown himself, but ignored by the company leadership—eventually led to the downfall of company.

As a qualified engineer, and by using his precision tools as a start at putting together the factory, Bill’s father became president of the new company. His real ace-in-the-hole was, of course, his son Bill’s wonderful engine design. Getting in on the ground floor, and with worldwide publicity, they figured that they would become the biggest name in model engines.

General Motors was a big name in autos, so they patterned their name after them. They chose Junior Motors as their name (Junior, meaning small, not Brown, Jr.). Of course, the Brown name was magic now, so they added that to the engine crankcase (Brown Junior Motor, inside the outline of a propeller).

When Junior Motors was getting started, Bill recommended an acquaintance named Walter to set up the assembly line. The vice president of the company was the son of a millionaire, who had big ideas about how it should be done. Bill’s father was supposed to introduce Walter to him, but had become sick, so Walter went to see the VP by himself.

However, when Walter heard what was being planned, he would have none of it, and left in a huff. So another engineer had to be found. Walter went back to his shop and made some more Brown’s that he called the Hurlman Aristocrat. (Ted Belcher has one that he says is a superbly made engine.)

Despite all of that, the Brown Jr. engine was an immediate success, even at $21.50. In the first two years of business they sold 5,000 engines. The weakest part was the curved breaker point arm that lost its elasticity with use. Interestingly enough, Walter’s was superior in quality. (Those in the know would put these points on the Brown for a winning combination.)

During this time, Bill went to Penn State College for three terms (until the money ran out). He was working on a mechanical engineering degree. He then came home and was hired on as a machinist at Junior Motors. This job is all Bill got out of inventing the first widely accepted model airplane engine. Of course, it also got a good job for his father, which pleased Bill.

More images of Bill’s first “High School” engine. Photos taken by Jack Conrad.

For several years, Junior Motors engines won most of the contests, and were world acclaimed. Bill’s father was at the top of company leadership. After regular working hours, Bill was back in the shop monkeying around. Bill reasoned that the large models being made were making it hard to get to a flying site. He realized that in order to start designing a smaller engine, he first needed a much lighter coil and batteries.

One day, he asked the company purchasing agent to find a coil of the finest enameled wire he could get. Bill still had it at the time of this writing (and I have a piece of it, too!). When word got back to company leadership, they did not like it! Bill was called into the office, and he said that Mr. Roberts spoke to him as if he were a small child, scolding him for wanting to make a smaller engine. His father concurred; he did not want it either.

Here is the “Statement of Policy” given to him:

Decided upon at a meeting of Mr. William L. Brown, and Mr. Edward Roberts in the presence of William L. Brown, Jr. on September 25, 1936. The Junior Motors Corporation at this time has decided to spend no further money in the development of a smaller motor than the present BROWN JUNIOR MOTOR for model airplane flying.

We feel that the present 1/5 h.p. BROWN JUNIOR MOTOR if adjusted properly can fly planes of a wing spread between 2-1/2 ft. to 15 ft. The reason the Company has decided not to make a smaller motor is because we feel that the present motor can be adjusted to fly such a small plane. Also, this same motor can cover the field of Radio Control. If there should be a larger or smaller motor, it would only reduce the number of sales of the present BROWN JUNIOR MOTOR.

Therefore, we feel that we want to bend all our efforts towards the development work of the Commercial size motor. Nothing in the above should discourage any individual from development efforts working outside regular business hours.

(Bill added this comment: The Junior Motors machinery, however, was now off limits for such developmental efforts.)

Therefore, the Policy of the Company is to train and inform the model builders that the BROWN JUNIOR MOTOR is capable of doing the work, which they require to enable them to carry out all their experiments in the model airplane line.

Soon after, Junior Motors put out a newsletter in an effort to get the word out. Here is what they said:

WHERE ARE WE GOING—BACKWARD OR FORWARD?

A few boys have started the craze for small gas powered planes, which is fine. Most of these boys do not know enough about present-day motors and planes to be at the top of the list. It is known that you cannot make many mistakes in the design of a high-speed small plane, and this is where the boys decided to use less power to overcome their faults in design. At a low flying speed, the adjustments are not so critical, but if you double the speed there would be some affect to the performance (sic) which may have been over-looked before.

The present BROWN JUNIOR MOTOR is as light as you can get it without sacrificing power, easy starting, and durability. If you want to run the motor in a very small plane which requires less power all you have to do is close the Choke Nut almost all the way and then reduce the amount of fuel by screwing the Needle Valve down to get your motor running fast but smoothly. By doing this you reduce vibration and power which makes it suitable for flying a small light-weight plane.

Bill Brown (left) with some of the members of the Science Park Aero Radio Club (SPARC), and spectators in the early 1960’s (1960-1961). SPARC was a radio control club started by several engineers at HRB Singer, in the late 1950’s. SPARC later became SCRC when the members expanded to include many non-HRB R/C enthusiasts. Photo courtesy of State College Radio Control Club.

Because Bill could not use the company equipment anymore, he wanted to distance himself from Junior Motors. Bill and a friend, Jerry Smith, started riding a motorcycle 200 miles each way on weekends to State College, Penn. Bill liked the area where he had gone to college. He bought tools on the time payment plan, set up shop in a garage, and built the Lykens Brown .12 engine. It was five times smaller than the Brown Jr. .60. The fine wire made coils were very light, and could be powered by pen cells, instead of D cells.

Even though he was ridiculed by his father and others that it would never work, Bill went ahead with it. He even put it on the big Brown Junior, and ran it with the tiny coil and pen cells. The Brown Junior company leadership would change nothing! Bill made Megow, the leading model kit manufacturer and mail-order firm, his sole distributor; thereby he did not have to advertise!

They sold about 100 Lykens Brown engines. Jerry eventually went back to Brooklyn, NY and made the Smith engine that looked like a tiny Brown Junior. When 1939 came, and Junior Motors found other companies were passing them by, they finally decided to make a smaller engine. With Bill still in the doghouse (even though he was still a machinist for the company), the job of designing the engine was given to Bill’s dad.

So, Brown Sr. redesigned the Brown Midget to a .29. Bill still had reservations about it, but it was put into production. The engine was a big disappointment, and Bill and his dad were both fired! Junior Motors struggled along for a while, but went downhill. This ended any serious work on internal combustion engines for Bill.

Addendum: Bill Brown—Mr. CO2

By Evan T. Towne

The use of carbonic acid gas, we now call it CO2, is not a new idea. In 1890, a Frenchman by the name of M. deGraffigny was investigating its use as a power source. In 1906, Traian Vuia hopped his full-size CO2 powered aircraft off the ground. This machine still exists in the collection of the Musee de l’Air, near Paris, France.

In February 1943, during World War II, Mechanix Illustrated magazine ran an article about William Lykens Brown, IV, and his “model airplane motor no bigger than a thumbnail.” This was Bill’s first CO2 that ran. The article shows him holding the tiny power plant, fastened directly to a CO2 cartridge. All you Old Timers know that this is the Brown Junior that brought model airplane engines to the whole world, back during the Great Depression. It is the famous Brown Junior engine!!!

Bill said, “6336 N. 10th St. Philadelphia, Penn. was the address of my father’s house where I grew up. He had a very fine workshop, which included woodworking and metalworking tools. Without this shop I could never have built the model aircraft engines.”

In September of 1931, Model Airplane News ran a story on page 25 called, “How to Make a CO2 Gas Engine Model.” The idea was to hook up six CO2 sparklets to a two-cylinder air engine, and run it for one hour and six minutes (calculated). One day in 1936 or 1937, Victor Fritz, a modeling buddy, remembered reading about it. He brought a bunch of cartridges and a three-cylinder Hoosier Whirlwind, plus a hypodermic needle, for Bill to check out. The supposition was to solder the hypo to the airline of the engine then puncture the lead seal in the cartridge to power the engine.

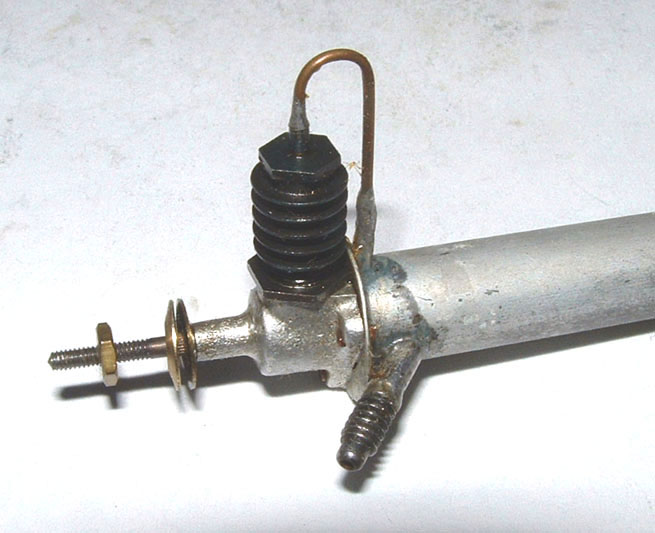

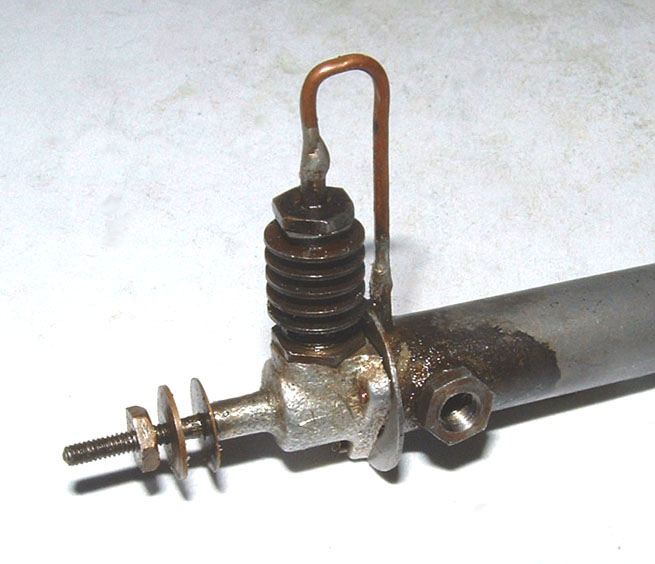

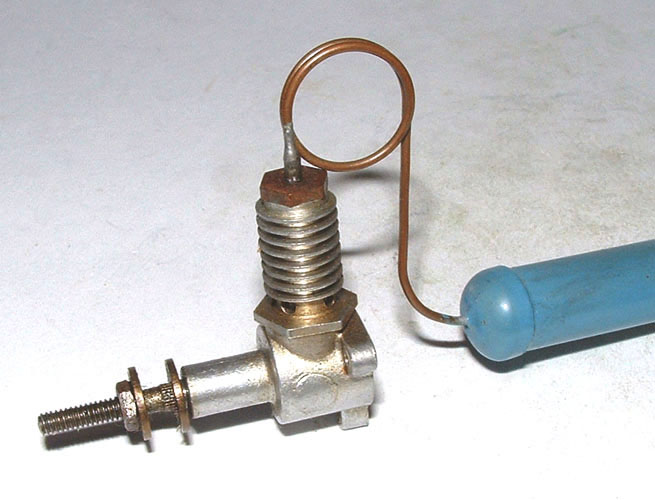

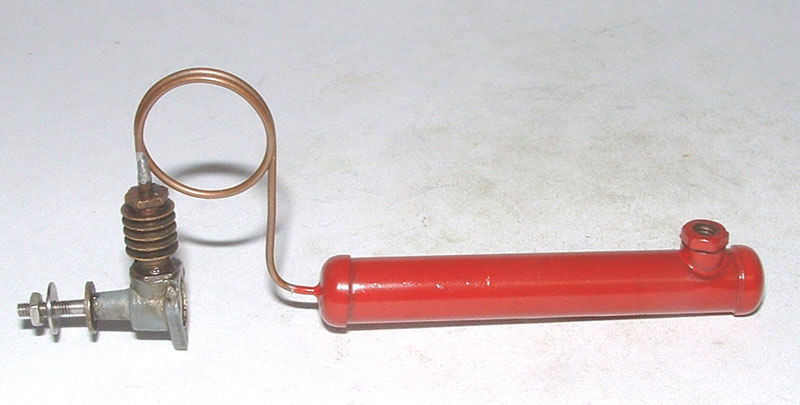

The first Brown CO2 engine, The “Mark 1,” which became the OK engines series—made in production by Herkimer Tool & Model Works in 1946.

It all sounded really good. The only problem was that the seal was not lead, but steel. When they attempted to puncture it, it just bent the needle. No problem, they were in Bill’s dad’s machine shop, so Bill just made a stronger “needle.” They then punctured the cartridge, and it started shooting around the room, bouncing off the walls. They were learning fast. The next time they locked a new one in a vise. This time the pressure went to the engine and Bill says that the pistons all started moving without waiting for their turn. This bent the connecting rods and cylinders all up, wrecking the engine!

Even while Bill was working for Brown Junior Motors, he was thinking small rather than big. Bill was reprimanded by the leadership for asking the purchasing agent to get him a spool of fine enameled wire, with the object of making a tiny coil—the first step toward a new small engine. They said a smaller engine was not needed—just put a Brown Junior in a smaller plane, and throttle it down. When they did finally decide to make a smaller one (the Brownie .29), Bill was not around to engineer it properly, because he had been fired! As a result, the other engine companies soon put Brown Junior Motors out of business. (Bill did put out his own small engine, the Lykens Brown .12. He put out about 100 of them, and did it on his own. They were sold through the Megow Company.)

During 1940, Bill went with a friend to a Philadelphia armory to see some small flying scale models. He asked the modelers if they would like to have a power source small enough to replace their rubber bands. The positive response sent him to his drafting board. The first CO2, with a calculated size of 118-inch bore and stroke (with a cubic inch displacement of only .0153), refused to run—but the second one did! More refinements coupled with a light steel tank, and Bill had the A-100. (100 has no dimensional meaning.)

On April 26, 1946, William Brown III and IV applied for a patent for the Brown CO2 Engine, Mark 1. They had a local company make a batch with seven fins, and “Brown CO2 Engine” stamped around the front of the crankcase. It was too big for them, so it was sold to O.K. Herkimer. They added a fin, and modified the crankcase and cartridge holder for mass-production.

Bill progressed through three different models. In 1947, he became an instructor at Drexel Institute of Technology, and set up Campus Industries. He saw a couple of problems that he wanted to help solve:

1. How to pay for your education.

2. How to get some practical experience in addition to education.

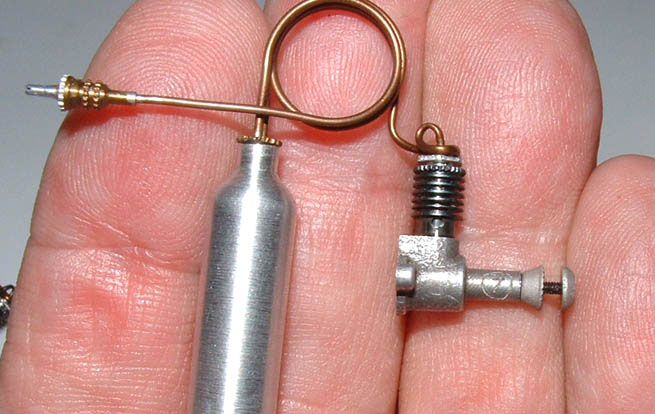

This tiny CO2 engine displaces only .005 cubic inches, and is seen connected to a CO2 cylinder via copper tubing.

Bill had been thinking about his little CO2 (that could be built on a jeweler’s lathe), and suggested that as their first project. Investors took his new prototype, A-100, to a flying field, and they all watched as engine and model flew out of sight—never to be seen again. Campus Industries was incorporated, and many A-100’s were made and sold, starting at $12.50 in three different models. There was a larger one called Campus Bee, and the Buz, which was made for another company.

Concerning the CO2, he said, “It was my father who did most of the work of dealing with the patent attorney. We both signed the patent as the inventors. He took all the engines larger than 3/16 inch bore, and made the deal with Herkimer Tool and Model Works, Herkimer NY. I took all the engines smaller than 3/16 inch bore, and helped establish Campus Industries, whose first product was the A-100. The Ludlow Street address is where Campus Industries moved to be near the Drexel Institute. Some of the workers hired were students.”

He added, “In 1950, I moved from Philadelphia with my wife and three boys, to Pine Grove Mills, PA, near Penn State University. My intention was to open a branch of Campus Industries near Penn State. The main office was to remain in Philadelphia. They moved to Adams Avenue on the other side of town, and farmed out the A-100 to the G&F Co. We thought they could do a good job, since they were manufacturers of watchmakers’ tools. They thought they could, too. Meanwhile, the Adams plant continued with the Bee engines. However, G&F made some ‘minor’ changes on the A-100, including: A zinc crankcase which was easier to cast, but three times the weight; a crankshaft with 1-72 thread, which doubled the weight of that part; and the stainless steel burnished pistons, which did not seal as well as the hardened tool steel lapped pistons. This resulted in the end of the A-100 production. By itself, the Adams plant was not profitable enough to stay in business, and had to quit. There were no more Brown CO2 engines until 1969.”

The GB-24 is a twin cylinder version combining two GB-12’s, displacing a total of a whopping .0014 cubic inches.

Reorganized under different ownership, Campus Industries added new projects. Finally, Bill elected to buy out the model side of the business, and form his own company to manufacture his own creations. He renamed the new company Brown Junior Motors, Inc., bringing back a very famous name to the world’s modelers!

In 1969, Bill came out with the first of a new generation of CO2‘s. He called it the Brown .005 (.005 cubic inch displacement). It was the same size as the Campus Bee, but it had a very light spun aluminum tank that could be re-filled from a cartridge loader. It sold for $24.95, and required a load and launch gun for $5.95. It was a difficult engine to make, and he could not keep up with demand for them. The magnesium crankcase was difficult to clean up, and it was hard to get a good piston fit with a blind bore. He made only about 1,000 total—500 of them with lapped steel pistons, and 500 with “Nylatron” plastic pistons. (Nylon contained a lubricant called Aluminum Disulfide. This made them black and they sealed well, but they also added more friction, according to Bill.)

After he had developed the light-weight spun aluminum tank, Bill took one and added a length of copper tubing to a nozzle with a tiny hole—about one-hundredth of an inch in diameter—and made a true reaction jet. He called it the Micro-Jet. It sold for only $2.95. The cartridge launcher for $5.95 could also be used with the .005 engine. Both of these came in waxed sandwich bags.

The zoning board gave Bill much trouble, and wouldn’t let him add new buildings to make manufacturing easier. Nonetheless, he redesigned and updated his engines, and added others to his line—all while working in rather limited facilities.

In 1973, Bill came out with the MJ 140 twin, and MJ 70—which was the updated .005, but not as hard to make. He also went to metric for size. (MJ stands for “Metric Junior”—cubic millimeters.) The old Campus A-100 was the next to receive a redesign. When Bill was finished with it, it weighed less, but produced twice the power. He called it the A-23, and it weighed only 1/4 of an ounce.

This A-100 engine is from Bill’s time at Campus Industries. The A-100’s were produced in 1947, and displaced .00153 cubic inches.

Bill’s early engines had four exhaust holes, and did not have serial numbers. Starting with the .005, serial numbers were used, and only three exhaust holes. The first generation engines came in boxes; the second came in clear zip-lock bags. The filler nozzles were first 1.5 mm in size, then the international size of 2 mm. Also, sometime after bringing out the Ansul adapter, Bill got word that some Ansul dealers were refusing to sell cartridges for purposes other than fire extinguishers—so he discontinued them. At times, Bill would start selling engines before he had printed instructions for that particular engine—but all instructions were about alike anyway.

He also told me that he had actually received money for the A-23 before the first one was finished and tested. I do not care to get into semantics, but my use of the word “engine” comes from the definition: any power source that is derived from the piston being forced down or by internal combustion is called an engine. Bill has just finished the tooling for the tiny GB-12. (The name stands for Gasparin Brown.) Bill gave me a beautiful cut away that I have mounted on my display paddle. As of July 1994, Bill was selling Brown Junior B-100, B-200, A-23, GB-12, and the GB-24.

Bibliography:

The information above was written by Evan Towne, but he lists these sources in his bibliography: An article in the February 1943 issue of Mechanix Illustrated; Several articles by Bill Cannon in Model Builder 1986-87; Information sheets and personal correspondence with Bill Brown himself; and an Article by Peter Chinn in the May 1992 issue of Aero Modeler.

The last of the Campus Industries engines, the “Campus Bee,” was produced in 1949. It also features a separate tank, and displaces .0052 cubic inches. A slight modification to this engine was also available, which was called the Buzz CO2.

This biography was provided courtesy of the Academy of Model Aeronautics’ History Project. You can access and read their complete biography of Bill Brown IV for more information, written by Evan Towne. More information on Bill’s correspondence with Czechoslovakian engine designer Stefan Gasparin can also be found there.

Bob LeDoux Recalls a Chance Encounter With Bill Brown

By Bob LeDoux

Between 1971 and 1973, I was a graduate student at Penn State University in State College, PA. I joined the local sailplane club that operated out of the State College Airport. The airport had a long history, going back into the 1930’s. The airport provided three intersecting wide turf runways. I think the longest of these was 4500 feet long and 300 feet wide. The airport owner and manager was an old and cantankerous gent named Sherm Lutz, who also shared much of Pennsylvania’s early aviation history.

Arriving early one Saturday morning to do glider preflight operations, I was approached by an older gentleman who was flying a small CO2 model airplane. Because of my modeling background, I recognized the Brown CO2 motor. I stopped to look at the model and told the man it looked like a Brown motor. The elderly gentleman said, “yes, I make them, I’m Bill Brown.” I was flabbergasted to think that on a rural airport I had run into a significant designer from my youth. He knew Sherm; they shared a lot of history.

The event is well remembered, almost 45 years later.

—Bob LeDoux

The B-100 engine is shown next to the GB-12 for size comparison. The B-100 was the largest CO2 engine Bill designed, displacing .006 cubic inches. The GB-12 was the smallest. The B-100 was first available in 1990. Tim Dannels noted that engines and sizes produced by Bill Brown were (in order of size): the B-100 (.006), MJ-70 (.004), Bee 70 (.004), A-23 (.0014), and GB-12 (.0007). Most of these were also available as twins at twice the displacement, making for a fascinating assortment.

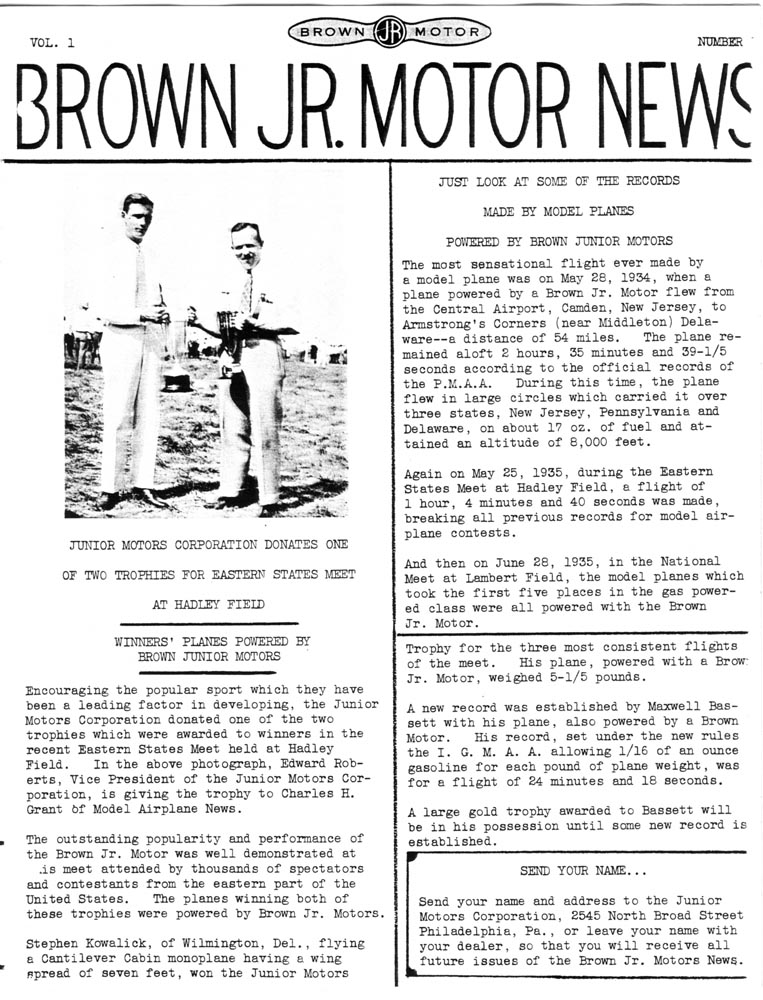

Company Newsletters

The Brown Junior Company put out a newsletter for some time. Jack Conrad sent us several copies for our files. Below, you can view Volume 1, No. 1, which was probably published around 1936. The Craftsmanship Museum has also archived copies of Volume 1, No. 2, and Volume 2, Number 1, thanks to Mr. Conrad.

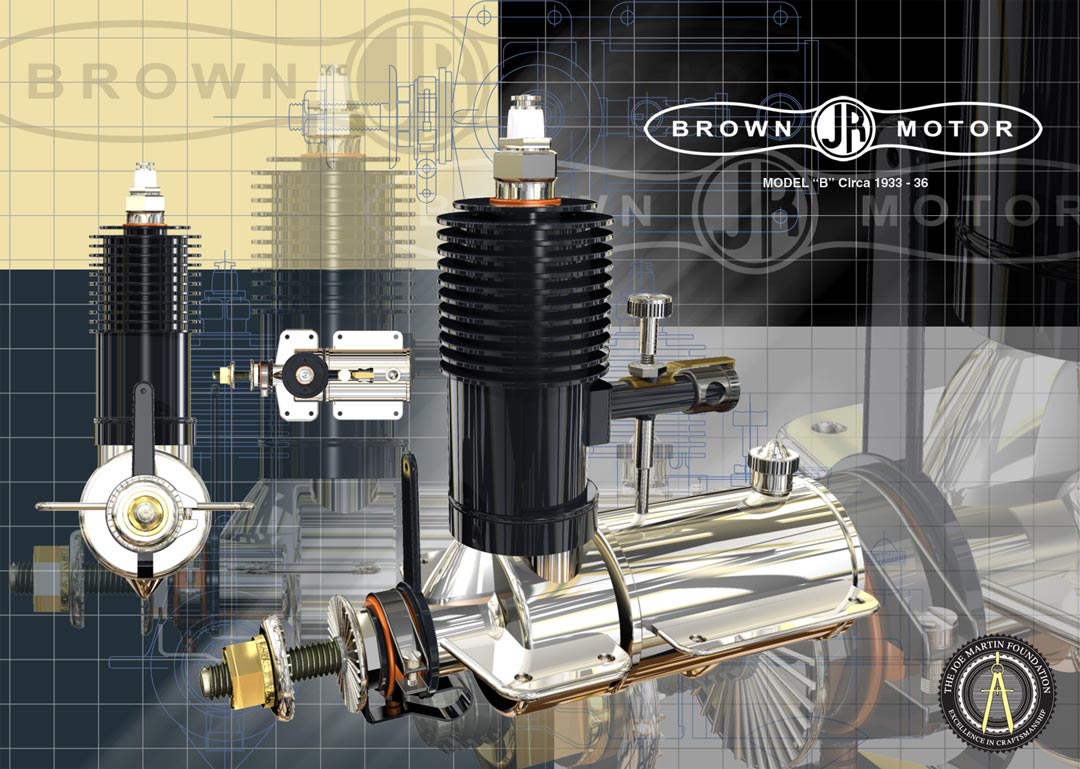

Artwork Honoring Bill Brown

By Charlie Tomalesky

Industrial designer and accomplished technical illustrator, Charlie Tomalesky, sent us three computer renderings to display. These images are in honor of Bill Brown IV, and his Brown Junior model airplane engine. Click on images to enlarge. Charlie was a big help on the foundation’s Seal Engine build.

This is a one-of-a-kind Brown motor, with the spark plug facing backwards horizontally, rather than upright. Photo by Jack Conrad.

William Preston’s Red Zepher plane—with Brown engine—made many successful flights. William went on to become a naval aviator, piloting a torpedo bomber in 1945. Engines like the Brown Jr. led many young pilots toward a lifelong interest in aviation.