December 26, 1896—1979

Outstanding Miniature Machine Tools From a Lifelong Tool and Die Maker

“It should be up to every individual, absolutely, to make his own way in life. This is absolutely necessary in order for creativity to exist. I don’t think you will find much creativity, or invention, in a society where there are too many handouts or giveaways, or where there is no desire to work hard at a job and excel in your work.” —John Aschauer

The following information was written and submitted by Jeff Bond and Mr. Aschauer’s daughter, Hilda, and granddaughter, Claudia.

Introduction

John Aschauer was a master machinist, toolmaker, and an extraordinary miniature machine tool maker. Like many other miniature builders, his models are literally works of art. He once conservatively estimated that he had spent more than 25,000 hours building over fifty machine tool models, as well as the many accessories that make up his miniature machine shop collection. That is equivalent to almost twenty years of full-time employment. His complete collection is on display at the American Precision Museum in Windsor, Vermont.

An Early Start With Tools in Germany

He was born Johann Aschauer, on December 26, 1896, in Sauerlach, Bavaria, Germany. Johann came from a humble family. His father was a railroad man who worked for modest wages, and always made sure that his family had enough to eat. Johann was the middle of three boys. He had an older half-brother, Josef, and a younger brother named Franz. When once asked what he remembered as his first tool, Johann replied, “I remember going out into the woodshed and picking up the handsaw. I held it a minute, then cut a piece of wood because I wanted to see how it would feel. I liked the way it felt, but the cut was cock-eyed. I couldn’t really hold the big handle, and it kept slipping.”

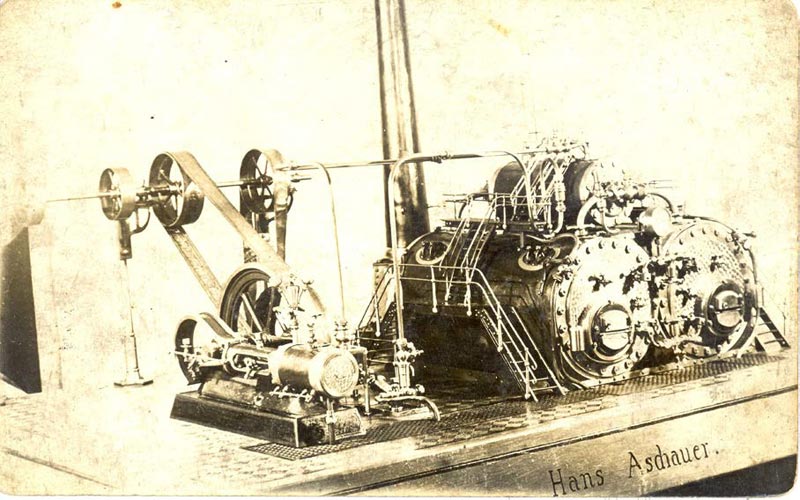

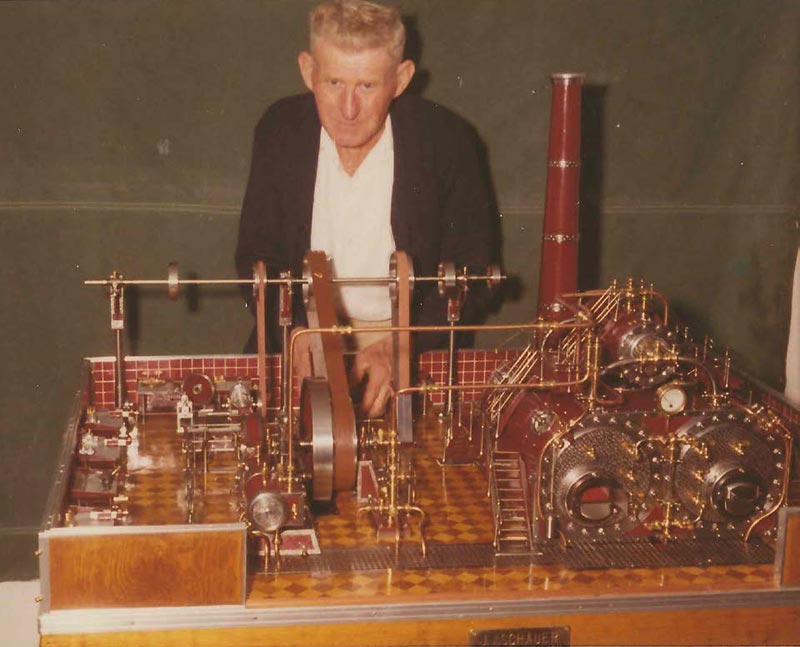

At the early age of 12, Johann began a three-year tool and die apprenticeship at Alois Stocker Machinefabrik GmbH (in Pfaffenhofen, Germany), which manufactured lumber mill saws. At this company, there was a double-boiler steam power plant that was used to drive line shafts, which powered all the factory machinery and equipment. Two years into his apprenticeship, Johann began working on a scale model of this double-boiler steam power plant. He used the windowsill in his mother’s kitchen as a work bench for the project. Johann would complete his apprenticeship at the age of fifteen, with the highest recommendation of his superiors. It took him another three years to complete the model, which he finished at age eighteen. This was around the same time that World War I began.

Johann “John” Aschauer’s first model, which took 3 years to complete.

At some point, Johann’s model was disassembled and stored in several suitcases in the attic of his parents’ house. It would stay there until he was able to retrieve it and bring it to the United States for reassembly following World War II. The model is now on display at the American Precision Museum. The piece is amazing for several aspects. First, despite being built by a fourteen to eighteen year old teenager, it exhibits very high quality craftsmanship. Additionally, it survived two World Wars in Germany hidden in an attic. During World War II, a bomb did strike near enough to his parents’ house that its blast tore off the roof, and blew out doors and windows. However, the model still survived.

John standing on the left in a family photo. In the second image he is pictured in his Army uniform.

Coming back to Johann’s upbringing, he was one month shy of nineteen years old when he joined the German Army (infantry) in November of 1915. He served in the German military for about three years, and was released in November of 1918. Johann suffered a slight bullet wound to a finger while fighting in one of several battles located in Flanders, Belgium. He earned the German Iron Cross for his service.

On October 1st, 1921, at the age of twenty-four, Johann married his wife Paulina Santer (“Paula”) who was nine years his senior. They had a daughter, Krimhilde Johanna (alternate spelling “Crymhilde” or just “Hilda”) on February 4, 1923 in Pfaffenhofen, Germany. This was during the height of Germany’s hyper-inflation crisis. At the time, a one-billion mark note was not enough to purchase a simple cup of coffee, and printing presses were working non-stop printing money.

From Germany to Canada to Detroit

John emigrated from Bremen, Germany on the S.S. Yorck on April 5th, 1927. He arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia on April 15, 1927, and briefly settled in Kitchener, Ontario.

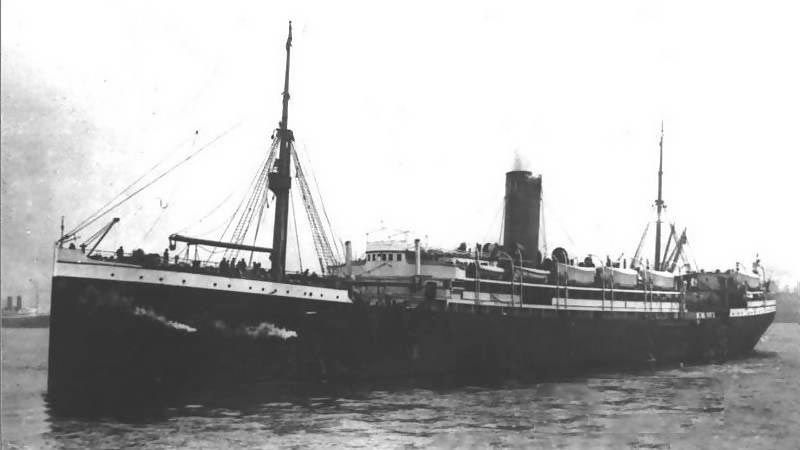

John’s wife, Paula, and his daughter, Hilda, would join him four months later. They left Bremen on August 2nd, 1927, and arrived in Halifax on August 12th. The two traveled on a similar ship, called the S.S. Seydlitz. The entire family settled in Kitchener (a German community known as “Little Berlin”) because Paula was Austrian, and the quota for Austrian immigrants to the U.S. had already been reached. This was because the Immigration Act of 1924 limited the number of immigrants allowed entry into the U.S. through a national origins quota. John’s younger brother, Franz, also came over and settled with them in Kitchener. While living there, John worked for Jackson, Cochrane & Company. This company made a full line of woodworking machinery.

Eventually, John immigrated to Detroit on May 6th, 1928, followed by Paula and Hilda on June 29th. A border crossing record that was found later on noted that John spoke good english.

The S.S. Seydlitz (pictured above), which brought John’s family to Canada four months after his arrival. John’s first job in America was with Jackson, Cochrane & Co. where he built woodworking machinery (an advertisement for them is pictured in second photo).

Work in the Auto Industry

Once in Detroit, John initially found work as a machinist, and a tool and die maker. Although records are scarce, it’s believed that he worked at the Century-Detroit Company, the Studebaker Motor Company, and the Hudson Motor Car Company. After that, he finally landed steady work at Ford Motor in Highland Park, and then moved to Ford’s River Rouge Plant.

According to U.S. census records from 1930, John was a toolmaker for an auto factory in the Detroit area. His family, including his brother Frank, were living in Highland Park, Michigan (Wayne County) at 12821 Trumbull Avenue. Their monthly rent was thirty-five dollars. During the beginning of the Great Depression, John lost his machinist job because of complaints that newer immigrants were holding jobs while other unemployed workers had been in America longer. Jobs were obviously highly sought after during this timeframe, and having a trade or skill—although valuable—was no guarantee of employment. However, in John’s specific case these complaints were more focused, as he was not yet even a citizen. When asked about this once, John said, “I lost my jobs because citizens complained about a non-citizen having work, and that was sensible. I had to wait five years to get my citizenship papers.” Records show that John became a naturalized citizen of the United States on January 3rd, 1934.

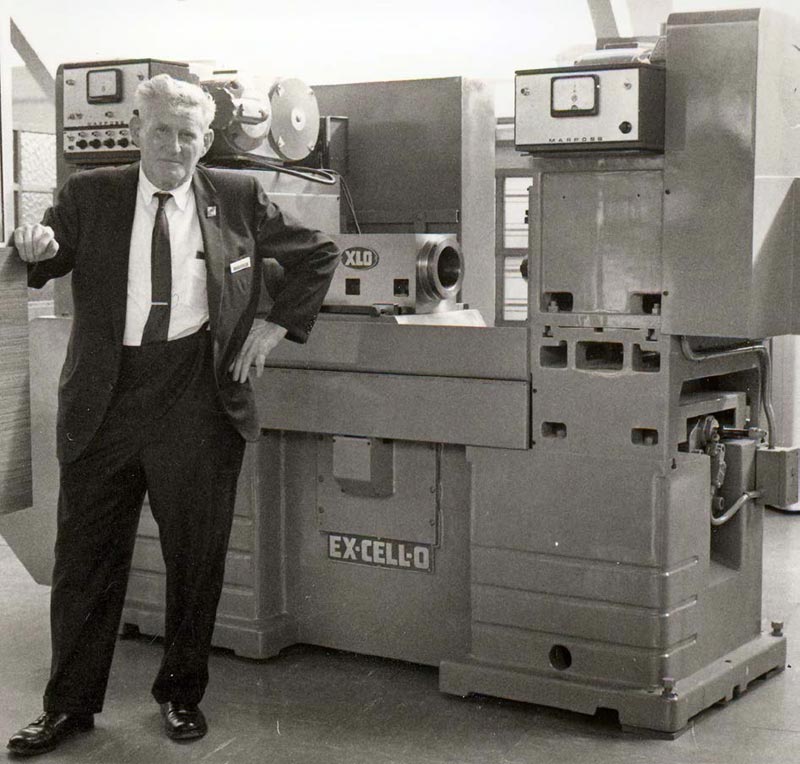

A 27-Year Career at Ex-Cell-O Starts in 1933

John began working at Ex-Cell-O in 1933, and retired from the company in 1960 after twenty-seven years of continuous employment. While employed at Ex-Cell-O during the later years of the Depression, he and his wife bought some land little by little until they had about five acres. During World War II, John and his family personally constructed an eleven-room stone house in Warren, MI, complete with a basement. Their level backyard became a small four and a half acre farm. They had a vegetable garden, and they also raised a few chickens, cows, and pigs there. During World War II, John was a “farmer” during the day, and a tool and die maker by night. The family used their own farm to put food on the table, and any extra produce was sold to John’s co-workers at the Ex-Cell-O plant. John sometimes worked different shifts, depending on various manufacturing needs at the time.

Unfounded Espionage Charges Result from “Suspicious Activity” in Home Basement

One interesting anecdote from John occurred during World War II, when anti-German sentiment and suspicion was very high across the United States. There was a lot of propaganda generated to be on the watch for suspicious activities, and for strangers asking unusual questions. This was particularly true in areas where efforts to support the war were especially important—like in heavy manufacturing towns where industrial operations might be concentrated. As a result of this heightened sense of security, John and his family were reported by neighbors as German spies. The neighbors thought that the family was having secret meetings to plan a sabotage on armored tanks, which were being built at the nearby Chrysler Tank Plant. Once completed, the nearly combat-ready tanks were transported by railcar along the Grand Trunk Western Railroad which ran directly behind John’s house. Neighbors were seeing lights on in John’s basement late into the evening—sometimes all night long—and felt that something suspicious was happening. What else could it be? Acting on this reported suspicion, an FBI agent visited the house, interviewed John and Paula, and explained that neighbors had reported them due to the constant basement lights. John then escorted the FBI agent downstairs to the basement, and showed him the homemade chicken incubator that he had constructed by hand. To keep the newly hatched baby chicks warm, a number of lightbulbs used in the device were kept on at all times. The FBI agent told John that he felt his neighbors had probably reported them out of jealousy, and that they had nothing more to worry about. One can only imagine the kind of discussion that probably followed at the FBI agent’s office.

The Aschauer family home in Michigan. Neighbors mistakenly reported the family as German spies during WWII, after seeing lights on in the basement at night.

Understanding the “How” and the “Why”

Now, John was noted as being able to fix almost anything, and when he did fix something it usually remained that way. He enjoyed working with his hands, and he always liked to understand how and why machines (and other things) worked. He built many items for himself and his family over the years.

In John’s last several years at Ex-Cell-O, he worked within their Special Machinery Division. He also worked in their welding area making various airplane components of the time. Due to the fumes generated from welding operations, this work was housed in a separate building. John’s formal education had ended at the age of 12 when he began that first apprenticeship. However, his engineering knowledge, and complete grasp of manufacturing and machining principles, would match that of the best graduate engineers of his day.

John was also a skilled trades member of UAW Local 49, and was issued UAW Journeyman card number 129553 on October 20th, 1977. His card was issued for the trade of Toolmaker. As often as he could, John would attend functions and events where his miniature machine tools were displayed. He enjoyed talking to others with similar interests, backgrounds, and experiences at these events. John absolutely loved the industry that provided him an occupation, and more importantly, a vocation.

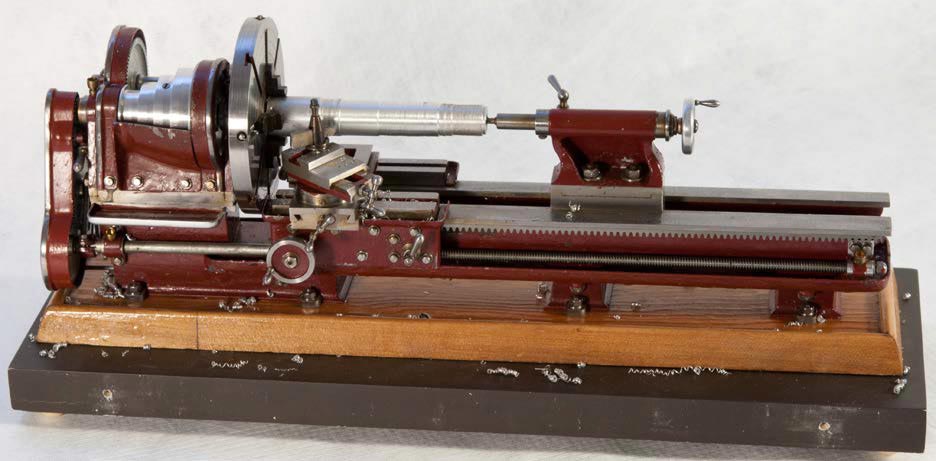

One of over 50 miniature tools made by John. Though hard to tell in the photo, this is a 1/16 scale model of a belt-driven lathe. (Photo courtesy of Ted Jerome)

Miniature Tool Collection Displayed in Numerous Locations

John’s complete collection of over fifty 1/16 scale models was first displayed in the Fall of 1967, at the International Machine Tool Exposition (EMO) in Hanover, West Germany. They have since been displayed at such places as: The International Manufacturing Technology Show (1968 and 1974); Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry; the UAW Skilled Trades Conference in New Orleans (1977); the Detroit Bank and Trust; the Detroit Historical Museum; California’s Museum of Technology; the Watervliet Arsenal (New York); Charlotte, NC; West Springfield, MA; and several industrial facilities and community anniversary celebrations throughout the country.

Entire Tool Collection Now on Display at the American Precision Museum

In 1972, John’s complete collection of incredibly well-crafted scale models was presented to the National Machine Tool Builders’ Association (now known as AMT—Association for Manufacturing Technology). Then in July of 1990, the AMT transferred the entire collection, minus eleven miniatures, to the American Precision Museum in Vermont. The eleven models not transferred were kept at AMT headquarters in McLean, Virginia, for display until 2010. After that, those models were also transferred to the American Precision Museum to be reunited with the entire collection in Windsor, VT. This fulfilled John’s one enduring wish that his collection would never be broken up, and ultimately kept together at a single location.

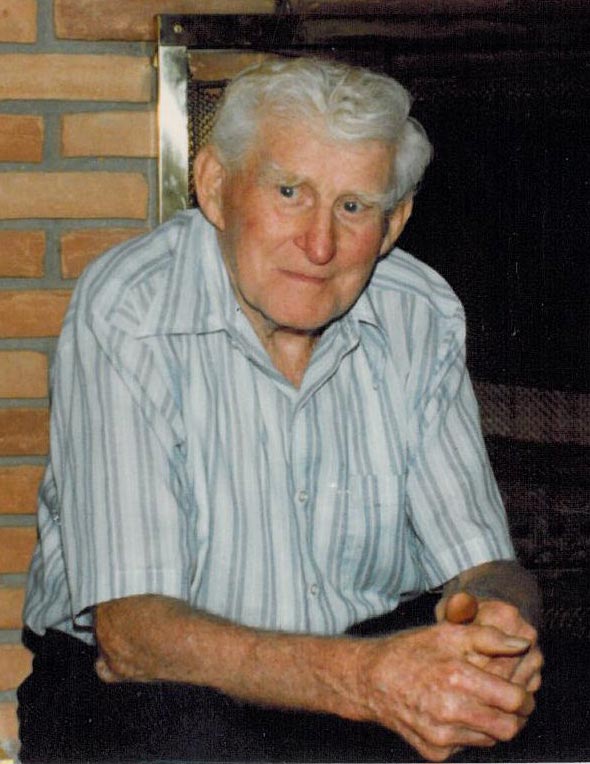

Unfortunately, John passed away in 1979 at the age of eighty-four. As of this writing, his daughter, Hilda, and three granddaughters—Paula, Laura, and Claudia—all still fondly talk of their grandfather, his models, and the shared memories of his legacy.

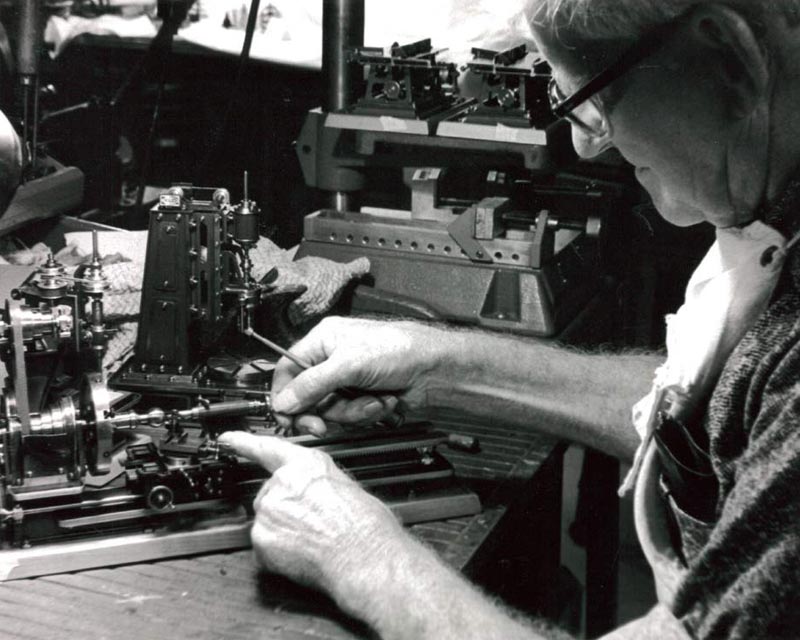

John in his early 80’s. In the second photo, John is pictured working on one of his 1/16 scale lathes.

No Plans or Drawings Used to Make His Models

When considering all of John’s accomplishments, one amazing fact about his models is that he made each one by hand, from memory, and with a lot of patience and love. He didn’t use any plans or detailed drawings, yet the models are incredibly reflective of each full-size machine that John personally worked with over the years. John used only small hand tools, emery cloth, a battery of files, and a small engine lathe which he designed and built himself. He also used a simple bench drill press, and a bench shaper. John motorized all of his miniature machine tools, and they all still worked at the time of this writing.

In 1974, NMTBA provided a specially constructed set of display cabinets which now house John’s collection. Overall, these models represent a complete miniature working machine shop factory that would be typical of the 1920’s-30’s. Every miniature machine tool actually works. In fact, John made each and every tiny screw, nut, and bolt. Every small hammer, file, and C-clamp was made to exacting detail. He machined every gear, and made every hydraulic pipe and fitting. John even turned out handles from bone, which he split, ground, and hand rubbed to size. John was a fine craftsman, a gentleman, and a gentle man.