For many centuries, before the advent of photography (or even electricity for that matter), artists of all types had established standards for what constituted craftsmanship in their fields. When photography did come around, there were many debates as to whether the images captured through these mechanical devices could be considered “art.” These days, great photographers are now recognized as artists in what has become a new form all its own—digital and film photography. Over time, opinions and processes change, but there is no knowing where future tools and developments may take us. In that sense, we are forced to consider what new artists in varying fields of craftsmanship may look like, and what tools they might use. With specific regard to metalworking, we are already in the midst of a great discussion about what the capabilities of CNC might be, and whether the use of such tools can indeed be considered craftsmanship in full. What might the new artists in CNC be called, and where can these tools take us?

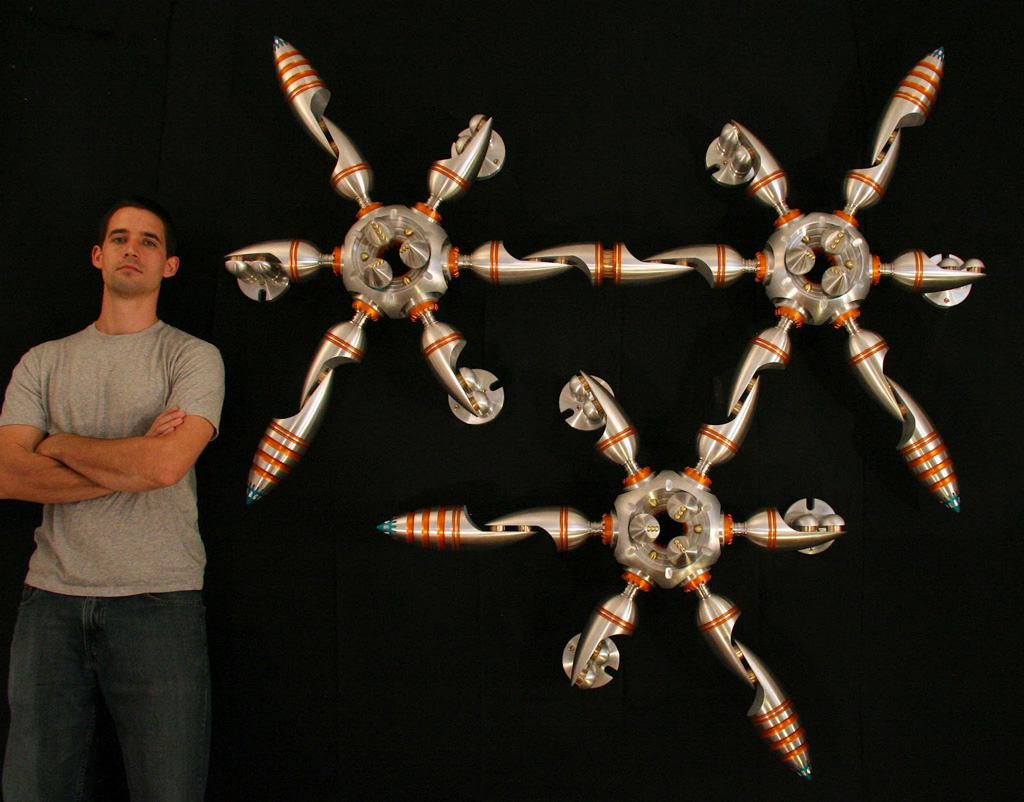

Metalworking artist Christopher Bathgate started out by simply purchasing manual machine tools and teaching himself how to use them. He would eventually upgrade the capabilities of his machines over time, and learned how to create drawings of his future projects in CAD. He even began writing the G-code used to produce parts with CNC on a machine he had built himself. After many years of practice, Chris is now highly skilled in the use of both manual and CNC machines. In general, he uses whichever process he feels will best accomplish the intended results for any given part. In his opinion, each has its advantages, and one is not “better” than the other. Visit his Craftsman page, or see his website to get an idea of the type of work he does, and the level of craftsmanship he is able to achieve.

Chris with one of his elaborate metal sculptures. This one is a large, multi-part creation known as ML 622254434732323.

Thoughts on Craftsmanship and the Use of Computer Control

By Christopher Bathgate

I was asked about my take on the whole craftsmanship conversation with regards to the relationship between manual machining verses CNC, and which qualifies as pure craftsmanship. Here are some thoughts to consider.

As a background on myself, I have never had any formal training as a machinist. When I was starting out, I had no one to teach me how to do anything, no one to ask questions, and no one to help me solve a problem when I got stuck. All I had was a stack of books and a computer. So I set out to teach myself, more or less ignorant of this notion that there was some sort of divide between what one type of craftsman thought was worthy of high praise over another. I just learned one project at a time, one tool at a time, and one process at a time. I started out on a small lathe and mill, and figured out the intricacies involved in using each. I sketched my ideas on graph paper at first, and figured out the best practices for making various shapes while using multiple techniques as opportunities arose. Slowly, over time I added new tools—rotary tables, radius cutters, boring heads and so on. I designed my projects so that they always required me to learn something new, and continued to build one skill on top of another. Eventually, I taught myself how to use a CAD program, and quickly realized that not only was it useful as a design tool, but it was itself capable of producing elegant drawings. These drawings, when given the same level of effort and attention to detail that I was applying to my machine craft, yielded technical drawings that were not only indispensable to making my sculpture work, but were themselves works of art.

After a good number of years, I began the long process of researching and building some of my own CNC equipment. I taught myself how to retrofit some manual machines with the proper screws, pulleys, and motors. I built my own drivers and control boxes, and learned how to write programs by hand. I wrote my part programs manually for quite some time, and only took up using CAD/CAM software well after I had fully mastered writing G-code without it. I did this to ensure that I would never have a gap in my knowledge base. I wanted to make sure I would be able to make changes to, and find and fix problems with, any code my software was outputting. Anyone who uses CAD/CAM can attest that this often happens. More generally, I wanted to make sure I was learning as much about every aspect of the process that I had fallen so very much in love with.

It all felt very linear to me. Never once did I feel like there was a quantum shift in my process, level of difficulty, or way of working. Adding the CNC equipment never really saved me much labor or made things easier. For me, it only added new layers of complexity to my work, and allowed me to explore ideas that would have been extremely prohibitive by hand—or even impossible. At no point along the way did I ever feel like any of it was cheating, or that I was making my job easier. Each new process had a purpose, and each way of working had its benefits and its drawbacks. Each of them provided me with greater and greater perspective on the things I had already learned, and allowed me to connect various pieces of information I might have otherwise missed.

In my mind, CNC is not inherently better than manual machine work. In fact, I don’t see how you could be any good at it at all if you do not already have a strong foundation in working manually. Knowing how to machine something on the fly is one thing. Telling a machine how to make a part entirely from your mind is another. It requires you to imagine every single step of the process ahead of time without missing any steps or making any mistakes, and that is before the first cut is even made. This is not necessarily an easy task if you don’t already know the finer details of what goes into the process you are writing a program for.

The way I see it, CNC is certainly extremely good at some things, while using a manual tool has its own strengths. I still use both types of tools on a daily bases for just this reason. I personally think part of being a craftsman is an intimate enough understanding of your processes to use the best tool to achieve the desired results, without allowing any particular dogma to dictate how you proceed.

As an example, it may actually be much more accurate to creep up on a very close tolerance cut using a manual tool, especially if it is a one-off part where you don’t necessarily need any repeatability in the process. Also, drilling operations are notoriously tricky (for me anyway) to fine tune in a CNC program, so it’s just smarter to drill most things by hand. You have a better feel for how things are going in the cut, provided the number of holes is manageable. On the other hand, in most circumstances it would be a waste of time and mental resources (we all only have so much) to try to mill a complex helix using a manual setup. It can certainly be done, but it requires building a very elaborate and specialized gear train, and rigging it to your manual machine to make the cut. If you really think about it, it is hard to draw much of a difference between building a mechanical gear train to make a cut, and building a CNC machine yourself to make the same cut. Both are problem-solving exercises with overlapping parts that yield the same result. It’s just that one solution has a very limited use while another is much more flexible, and can be used in many other ways. It’s the old “working smarter not harder” thing that I think is a better indicator of a craftsman.

That brings me to another thing that often comes up in the discussion of CNC. That would be the myth of CNC as “hitting a button and a part pops out.” Since I mostly make one-of-a-kind objects, I tend to work on parts in fairly small batches. CNC is great at making life easier if you have to make ten thousand of something very boring and simple. But it’s actually not very efficient to draw up a part, create a program, set up the machine and the tooling, and test the program—all to make just one or two parts of something relatively straightforward. So I frequently make things on my manual tools when it makes sense to do so. On the other hand, I enjoy the challenge of designing things that can only be practically achieved on my CNC equipment. I also enjoy the process of writing elegantly simple G-code to achieve complex parts. It gives me another way to appreciate some of my designs, and has changed my perspective of how I think about the act of creating geometry. It has given me another opportunity to grow as an artist and as a craftsman.

As an artist working with machine tools, I tend to take most of my inspiration directly from my process. Because of this, I tend to see every new tool, process, and piece of information as an opportunity to be inspired. To create some new and elaborate work of art that is reflective of both my imagination and my love of technical problem solving. I would no sooner limit myself to one way of working than I would limit myself to just one or two colors if I were an oil painter. All of the various tools I use add to my visual vocabulary or mechanical palette. Which is why, in addition to teaching myself machine work and building all of my own CNC equipment, I have also set up my own homemade anodizing line and powder coating booth. I have dabbled in electro plating, acid etching, gun bluing, and a slew of other interesting related processes. I am even currently in the process of constructing a homemade 3D printer. What for? I am not even sure, but I feel that it must have its uses, and I intend to find out. It would seem to me that all of these things, when used for what they are best at, can add wonderful new dimensions to one’s work. I would never consider any of it lazy or cheating. Nor do I believe craftsmanship should be limited to hand work any more than I think surgeons who operate using robots to augment their abilities are any less talented at what they do.

So at the risk of rambling on, I’ll bring things back around to the question of where one draws the line between what qualifies as craftsmanship and what does not. I think a most fitting analogy lies in history, with the development of ceramics as an art form. Before the invention of slip casting, highly skilled potters were needed merely to produce the stoneware used for everyday life. But around the 18th century, the invention of slip casting started to change all that, and before long most ceramics where being mass-produced by relatively lower skilled workers. This created a vacuum in which the most talented ceramicists were no longer needed for the mundane act of making shingles and bowls. They were now free to practice their craft purely for the joy of it. Because they were no longer limited by the demands of society, they were able to experiment wildly, and elevated their work to the level of an art form. The results of which can be seen in museums around the world.

I think we are seeing something similar today. Modern manufacturing has created a space where there are a great number of craftsmen practicing a way of working that no longer has a place in a modern factory. There is room now to explore these machines and techniques for what other purposes they might serve. We can now mine them for their worth as a means of personal expression. That is what I hope to achieve with my work, and it is what I think many great machinist are working towards as well. So if you ask me where I would draw the line on craftsmanship, I would not say it should be between one particular process or another. Instead, it would be between what we would consider a mass produced, mindless commodity, and a lovingly crafted, one-of-a-kind object that can be appreciated for what it is, what it does, and what it represents as a technical and creative masterpiece.