Industrial Archeologist Reverse Engineers the Past With His Scale and Virtual Models

Bill Gould with a 1/2 scale model on the desk, and a 3D CAD model on the screen. Both illustrate a telescope made by Joseph von Fraunhofer, which was the largest telescope in the world in 1823. Bill’s craftsmanship inhabits the world of the real, as well as the virtual.

About Bill L. Gould

Designer—Craftsman—Modelmaker

Bill Gould successfully turned his childhood passion for “making things” into a lifelong career as an artist, product designer, and professional model maker. Self-employed for over 34 years, some of Bill’s clients included: Pacific Fast Mail, Kemtron, Texas Instruments, Mattel Toys, WD-40 Company, CBS, Revell Models, Monogram, General Telephone, Polaroid, and Fallbrook Engineering.

Bill had always been drawn to all things mechanical. Born in 1946, both of his parents were artists. His grandfather was a noted architect, and his great-uncle, Frank Crowe, was the Chief Engineer of the Boulder Dam construction project. Following suit, Bill had repaired a neighbor’s typewriter at just five years old, and by twelve he was winning awards for model railroading projects.

While just a Cub Scout, Bill manufactured kits for the Nike missile, and even “lectured” at the local library. By fourteen, Bill was machining brass patterns for model railroad manufacturers, eventually creating some 500 patterns over a 30 year period! During high school summer vacations, Bill would work in a precision machine shop operating a tiny Levin turret lathe. He invested his earnings in machine tools.

Bill created this 1/12 scale model telescope for the National Geographic Society’s Centennial Celebration, at Explorer’s Hall in Washington, D.C. The original telescope was made by Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787-1826), who discovered the dark absorption lines in the spectrum of the sun now known as Fraunhofer lines.

College and Early Career

Oddly enough, Bill’s primary interest at that time was technical theatre. He studied it throughout high school, and then while enrolled at Cal State University, Los Angeles. He even worked professionally in that field for several years. Bill started his first business while in college, making gift products and custom furniture, along with his continued pattern making and kit design. He distinctly remembered a period during which he was juggling college, his business, stage managing two shows, and working with Richard Dayton on the models for the Petticoat Junction television series—all at the same time, on fours hours of sleep a night!

It was at Cal State that Bill’s first love of model making would become his second love, when he met Geri Jimenez, an aspiring actress in the theatre department. He proposed to her at a model railroad convention, and they were married in 1969. The couple celebrated their 38th wedding anniversary at the time of this writing (2007).

Feeling burnt out with theatre, Bill decided to become a model maker full-time. He joined the model shop at Hughes Aircraft Company in 1971. The Hughes shop primarily focused on woodworking. They had a 96″ swing ‘T’ bed wood lathe, a 24″ jointer, a 48″ planer, some 20 hp table saws, and two huge bandsaws.

Although a skilled woodworker, Bill’s job involved precision machining. There were few metalworking tools in the shop, so he was allowed to request practically anything that he needed. Naturally, he asked for a Tree Knee mill, and a fully toothed Monarch EE metal lathe—considered by some to be the “Rolls Royce” of precision tools! Bill worked on the TOW, Phoenix, Falcon, and Sidewinder weapons systems, along with the Anik and OSO satellites. He received commendations for his work.

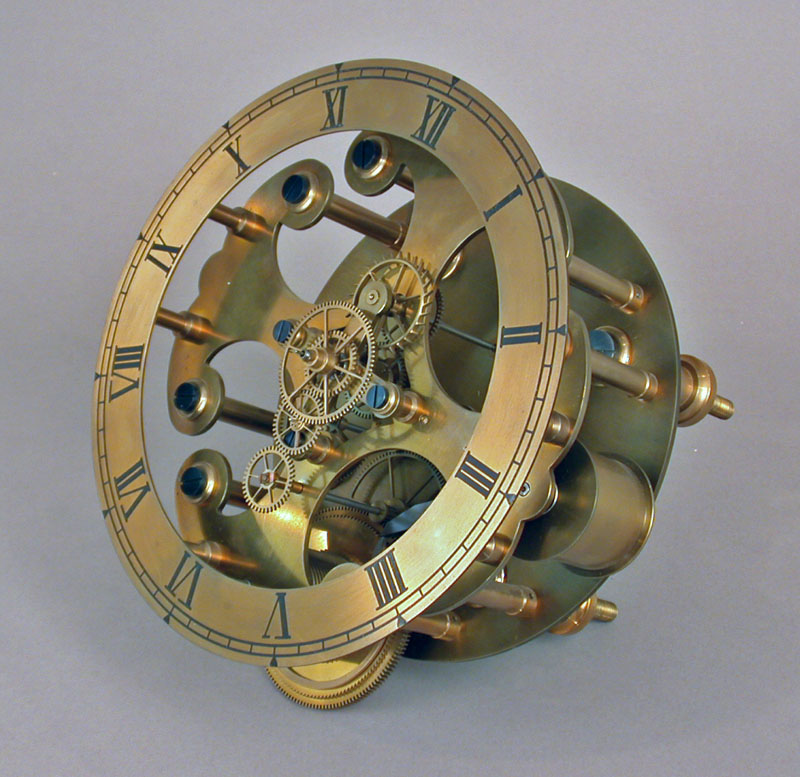

This clock was a work-in-progress since 1973! Bill took a design by Claude Reeves, and reconfigured it from a gravity escapement to a Graham Dead Beat (yet to be made)—which was moved to the front of the clock. Bill had plans to make a new dial, and since the piece was unfinished, it had yet to be polished or lacquered. All parts, including gears, were made by Bill.

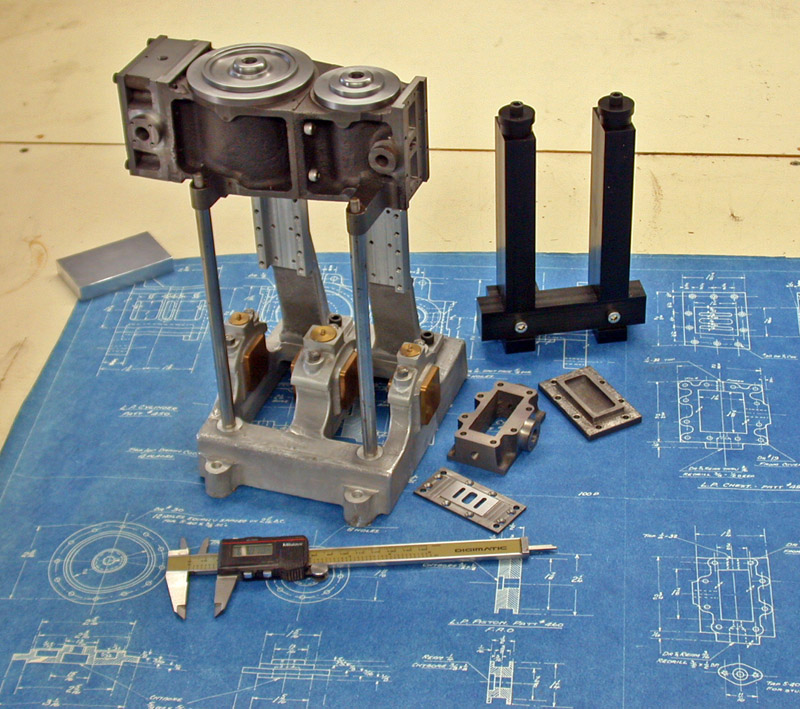

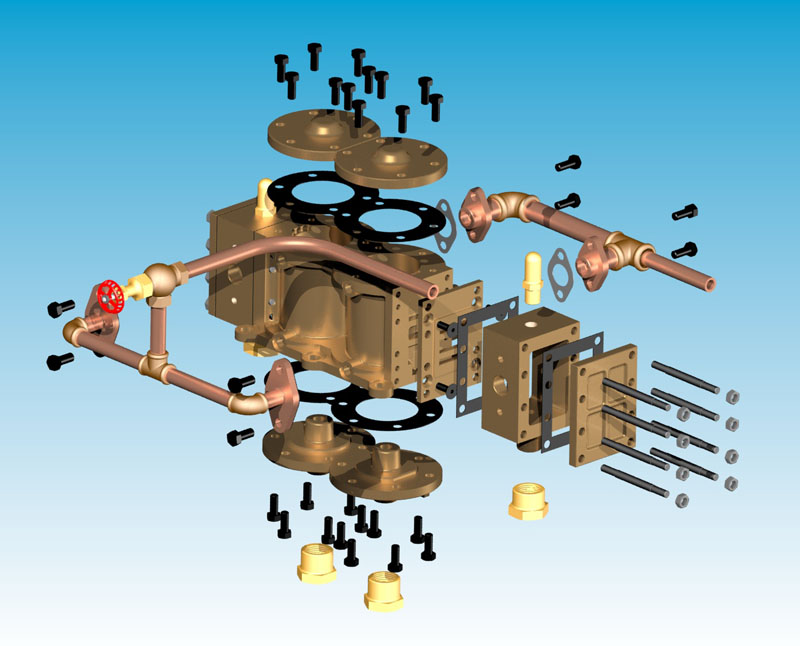

This classic Coventry twin compound steam launch engine was put back onto the bench after a 30 year hiatus! Bill was inspired by the SEAL Engine project. Note the alignment fixture for locating the many loose parts during machining.

Striking Out a New Path

In 1973, Bill decided to leave Hughes Aircraft. He and Geri started Gould Studios with only $500—and no clients! Needless to say, it was a tough beginning for the business that they would still share some 34 years later. Bill worked part-time as an engraver during the first year. However, as a result of the coming Bicentennial, he became very busy sculpting models for commemorative medals and coins. Additionally, Bill sculpted the Rancho San Rafael Memorial in Montrose, and also made another sculpture of a heroic figure for the Orange County Courthouse. Of course, prototype and museum model making continued throughout that time for Bill, with an ever growing client list.

In 1977, Bill added plastic injection molding to his arsenal, and shortly after launched The Gould Company. Producing a line of plastic model railroad kits, the company rapidly became known as a quality leader in the hobby industry. Bill made all of the tooling with the help of Brian Leppert, a fellow model railroader and exceptional engraver. Plastics quickly became their primary focus.

They soon outgrew their facility and moved to a large industrial building, adding more plastic machines and a packing line. Geri managed the office. The line was sold in over 1500 retail hobby shops in nine countries. In 1987, Bill sold the kit line to Tichy Train Group, and it was still on the market at the time of this writing.

Eventually, Geri and Bill moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he turned entirely to product design and prototype modelmaking. He mainly produced designs for consumer products and medical devices, while Geri focused on sculpture. Tired of the snow, they returned to California in 1997 to be closer to Bill’s primary medical device clients.

However, a major turning point occurred in 2001. Bill had seen a steady decline in sales of his prototype models, largely due to the impact of CAD design on the product development cycle. Simply put, hand-fabricated prototypes were seldom required now that designs were created on the computer, and sent out for rapid prototyping. Knowing that he needed to join the crowd, Bill consulted with his clients, and settled on the program SolidWorks®. This was considered the industry leader for product design. To speed up the learning curve, Bill enrolled in the ROP (Regional Occupational Program) at Palomar College. The ROP was a California state funded program to retrain working professionals for new job sectors.

Being a “T-square and drafting board guy,” with no CAD experience, Bill had a frustrating start. Fortunately, he recalled that, “the lights went on” after about three weeks, and he finished with an A in the course. Bill then did the same with the advanced SolidWorks class. By 2007, CAD design would account for some 70% of his work.

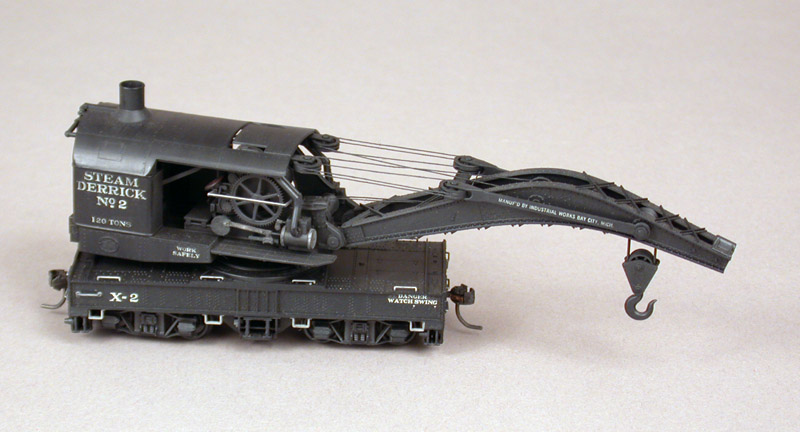

This model 120-ton industrial Brownhoist crane was the first injection-molded plastic, HO scale kit produced by The Gould Company. It is still regarded as possibly the finest kit ever produced! The kit contained over 200 precision plastic parts, each of which fit perfectly.

Becoming a CAD Master

Bill would eventually become an award winning CAD designer with an unusual twist, combining his expertise in SolidWorks with his lifelong passion for the history of technology. Much of his work became focused on the field of Industrial Archaeology. Bill’s SolidWorks model of the Mason Bogie 2-6-6T narrow gauge locomotive, requiring over 400 hours of research and computer time, was awarded 2nd runner-up in the SolidWorks 2006 International Design Competition. The awards were chosen from hundreds of designs by major firms from around the world.

A feature article on this project was published in the May, 2006 issue of Cadalyst Magazine, a leading CAD trade journal. Bill was also interviewed for podcasts, and featured on numerous websites. Full color lithographs and digital blackline scale drawings of many of his projects were also offered on the Gould Studios website for a time.

Ultimately, an increased focus on CAD design allowed Bill to downsize his model making business. By 2007, he was only making models for very select clients, and was finding time to work on many unfinished personal projects. Those projects included a skeleton regulator clock, a 3-1/2” scale live steam locomotive, and a Coventry compound launch engine. Each of those projects were started some 30 years earlier, but had been set aside due to time constraints.

Bill’s well-equipped shop included: a Bridgeport mill, a high precision Aceria mill (Swiss), a fully tooled Peerless watchmaker’s lathe, a 1907 belt-driven Potter 7” x 18” Instrument lathe (his favorite), and a large 13” x 40” engine lathe. Bill avoided CNC (farming it out) in favor of manual machines, which were better suited to one-off prototypes. This included Deckel 2D and 3D pantographs which were also perfect for his miniature work.

Bill’s 3D templates were often cut for him by others on CNC, using his CAD models. The advantage was that the template, say at 10:1 ratio, could be rapidly cut in acrylic with large cutters (1/8″ diameter or less). He then machined the final product or mold cavity with a .012″ diameter (down to .004″) four-sided cutter, at up to 30,000 rpm.

Bill’s hand engraving tools (gravers) were given to him 35 years prior, by a close friend of his dad who had used them as an engraver at Tiffany in 1917. Many of Bill’s hand tools dated to the late 19th century. Additionally, Bill was an accomplished writer, with many articles in national magazines like Sky, Telescope, and Live Steam.

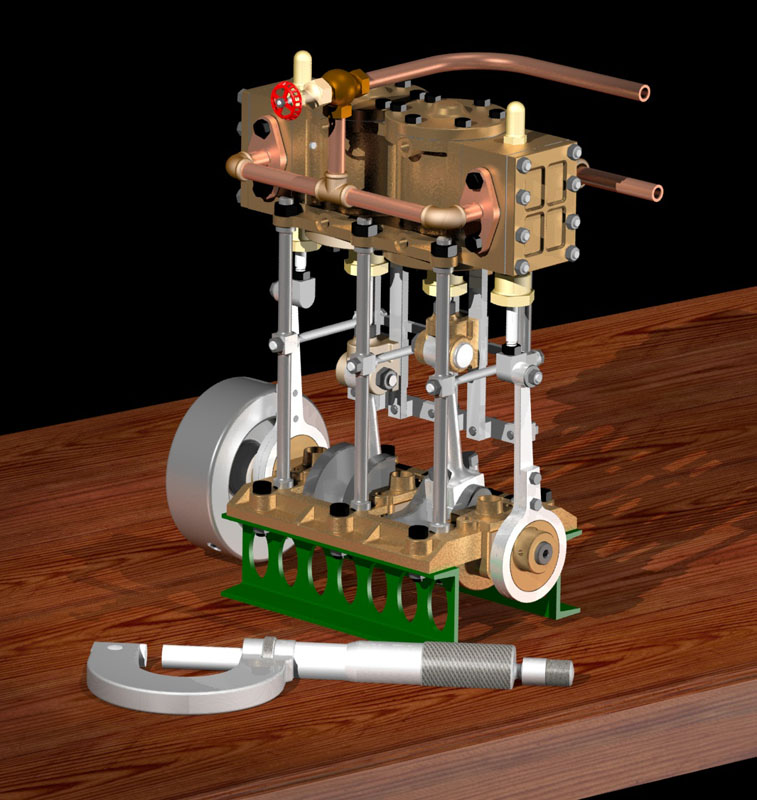

A SolidWorks/PhotoWorks CAD rendering for a live steam model of a Pinnace Launch Engine. The model has a 3/4” bore and stroke, and would have made an interesting kit. Some of Bill’s CAD models can still be seen on the Gould Studios website.

On top of all of that, Bill also crafted musical instruments and Native American style flutes. He had made over 250 instruments by 2007, most of which were made for recording artists and performers. Many of them were constructed in a traditional manner. Bill hand-carved them from split branches—often willow or elderberry from his own property—as well as cedar, walnut, and some exotics. Bill’s wife, Geri, is Native American from the Gabrielino/Togva tribe, or San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians. Bill and Geri were musicians in there own right, with a well-equipped home studio. The couple regularly recorded music together or with friends.

More of Bill and Geri’s work can be seen on the Gould Studios website. You can view many of Bill’s CAD renderings for different projects. At the time of this writing, Bill was also working on a project to develop a series of renderings of classic hotrods and race cars, which can be seen in the photo section at the bottom of the page.

Interestingly, Bill’s CAD drawings of the Miller 91 race car were used to produce a 1/4 scale model using 3D printers to make the parts. Watch Bill’s race car plans come to life.

One of Bill’s projects was to model classic race cars in highly detailed 3D CAD. The Miller 91 was a popular race car of the 1920’s and 30’s. This particular version was the 1928 Perfect Circle Piston Rings sponsorship #3 car. This rendering was used to make the 1/4 scale model in the video link above.

An Essay on Craftsmanship

Bill was kind enough to contribute this thoughtful essay on what craftsmanship means to him, and how important it is to the preservation of culture. We appreciate the honesty and insight from a true craftsman.

Additionally, view more photos of Bill’s craftsmanship and design work.