1934—2019

A Collection of Models that Represent Over 400 Years of Wheeled Transport—From Carriages to Formula 1 Cars

Joe Martin Foundation Craftsman of the Year Award Winner for 2005

Building the Wingrove Collection

For seventeen years, Gerald Wingrove was devoted to the business of light engineering as a centre lathe turner. Seeing no future in that vocation, he decided to turn his hobby as a model engineer into a full-time job. So, Gerald went to work as a freelance designer and patternmaker for film, TV, jewelry, and toy companies. He did work for companies like Meccano (Dinky Toys), Mettoy Playcraft (Corgi Toys), and others. In 1967, Gerald received a commission from Lord Montagu of Beaulieu to build a series of fine detailed scale models. These models were for the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu, in the south of England.

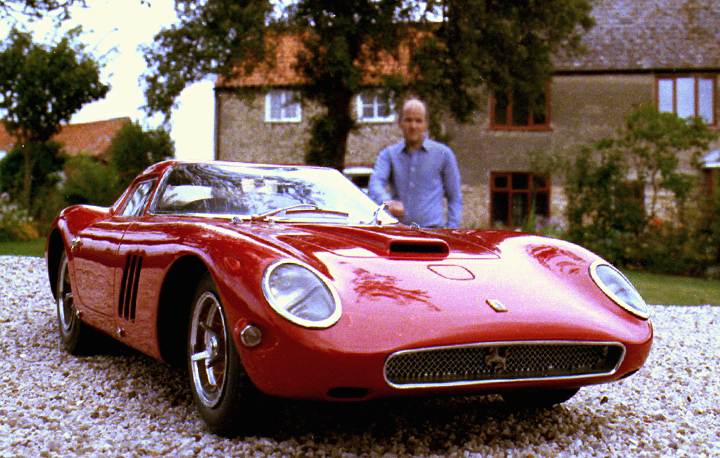

Other similar projects followed, as collectors became aware of the quality of Gerald’s work. He soon found himself being invited to visit some of the best private car collections in Europe and the USA, to document and reproduce in miniature some of these elegant works of “rolling sculpture.”

As he collected photos and data on the cars he was to build, Gerald also became interested in other aspects of carriage building—dating back well before the automobile. Gerald would come to document the fascinating world of the elegant carriage, which is all but forgotten today. The Wingrove Collection now represents a comprehensive and unique record of nearly four hundred years of the art and craft of the “carrossier.” It illustrates the development of fine personalized wheeled transport.

With a base of over 10,000 detailed photographs covering more than 200 vehicles, it was believed to be one of the largest and most comprehensive car and carriage data collections available. Gerald even made scale plans available for the models he built, so that others could recreate them in accurate detail. His photo and plan portfolios have also been used for full-size automobile restorations.

Getting Started in Model Making

Now, Gerald Wingrove got his start in model building in 1954, with two 1/43 scale Maseratis. The first was a kit of a pre-war GP car, while the second was a 50% scratch-built, post-war example. Both of those models had bodies carved from hardwood. Around 1966, Gerald had a chance discussion with a dealer in the model world. During this conversation he learned that there was a certain lack of supply in the field of high-end scale model cars. With that information, Gerald set out to further educate himself in the world of automobiles.

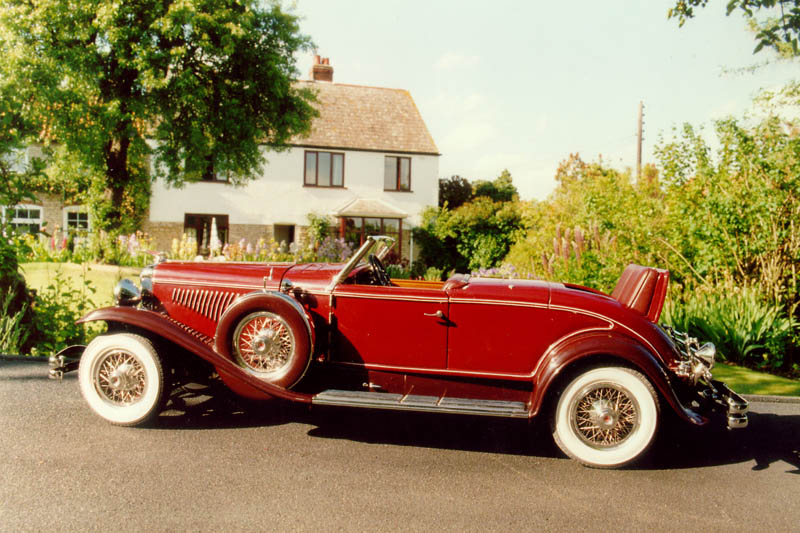

He frequented his local library and book shops over the next several months, and went through numerous glossy coffee table books. Gerald sifted through countless documentation of just about every conceivable machine that had four wheels. He was particularly inspired by an illustration of a Torpedo Convertible Victoria SJ Duesenberg from 1934, in deep maroon by Rollston, J517. Although Gerald had never heard of the make before, this to him was a real CAR—elegant, sophisticated, powerful, visually stunning, and alive.

During the next two years, Gerald discovered and joined the Auburn Cord Dueseberg Club based in the US. He collected enough general data to draw up a set of working drawings for a chassis, and made a set of wire spoked wheels (his first), and the main parts for the first engine. In fact, Gerald did all of this while still working full-time as a centre lathe turner.

Then in 1968, on a whim, Gerald decided to write to Lord Montagu at the National Motor Museum. He wanted to see if there was any future in model making for the institution. To his surprise, a positive answer came back, and he was invited down for an interview. At the time, Gerald only had a set of Duesenberg wheels and tires, and a partly made “Duesy” engine.

Fortunately, on the strength of those parts alone Gerald was invited to take on two projects for the museum. The first project was to produce a series of models showing the evolution of the sports car. The second was to build a model of the world championship Formula 1 Grand Prix car each year.

This commission, along with some toy development work that he was already undertaking for Mechano Dinky Toys, was sufficient impetus for Gerald to give his notice at the engineering company. He would leave the job that he’d spent the past 17 years with, and set himself up as a freelance model engineer.

Unfortunately, neither of these commissions necessitated the making of a model Duesenberg, or even a model with full engine detail for that matter. The scale that he was given was also somewhat smaller, at 1/20, than what he had personally decided upon (1/15). However, Gerald was content to settle with that for the time being. Regardless of scale, he had his work cut out for him.

Gerald had to contact the owners of the subject vehicles for the two projects, collect data, draft plans, and make the models to museum standard in metal. At the time, Gerald had not actually accomplished the latter task with a complete model—as the first Duesenberg parts were never finished.

From the start, Gerald quickly realized that he would need to make a number of special tools and patterns to produce a given model—whether he was building one or several of them. He noted that it was taking nearly as much time to make these tools and patterns as it would to produce an individual model from them.

At the same time, Gerald also started receiving requests from the owners of the full-size cars. They wanted to know, considering the fact that he was going to use their cars for the museum model, if he couldn’t also make one for them at the same time. Lord Montagu had no objection to this, and Gerald pointed out that it would be no greater cost to the museum, as the tooling would be shared. As long as the models were not produced in any great number, there were no objections.

As the models started to materialize, so did Gerald’s articles, which would circulate in the motoring press and model magazines. These generated more work, and it wasn’t long before the Wingrove name reached the US. Shortly after, Gerald received his first orders from across the pond. It was in 1973 that he made his first trip to the States to deliver the first models to an American collector. During that trip, Gerald was able to visit several museums and collections in the US. Perhaps most notably, he was finally able to get a firsthand look at the Duesenberg cars that had come to captivate him.

In the summer of 1980, Gerald met Phyllis Millar-Watt. They were married that November, and began a partnership as husband and wife—but also as miniaturists. Although Phyllis did not have any training in the area of drawing, she decided to try her hand at creating plans for the miniature cars. The plans were based upon dimensions, notes, and photographs taken by Gerald from existing full-size cars. Phyllis soon discovered that she had an enormous talent for drawing and painting. She began turning out drawings that complimented her husband’s work in structural materials.

After this, Phyllis set out to learn all of the processes involved in building the miniature cars themselves. She mastered soft soldering, silver soldering, lathe work, milling, and then began building engines and chassis! With this, Phyllis and Gerald began a new life working side by side in their workshop building the miniature cars. They also assisted each other with the necessary research for creating more books on their model subjects.

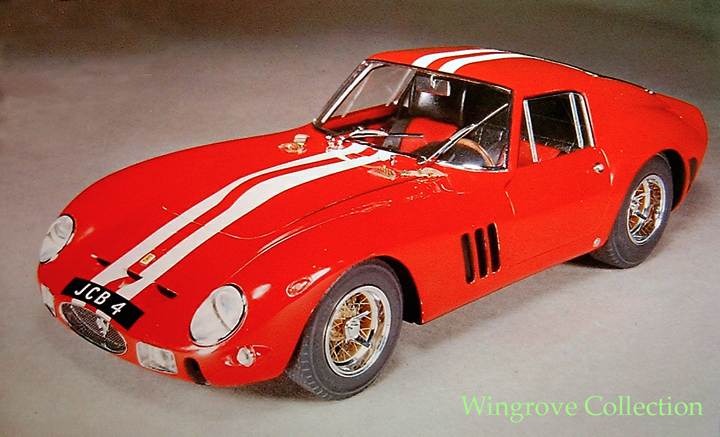

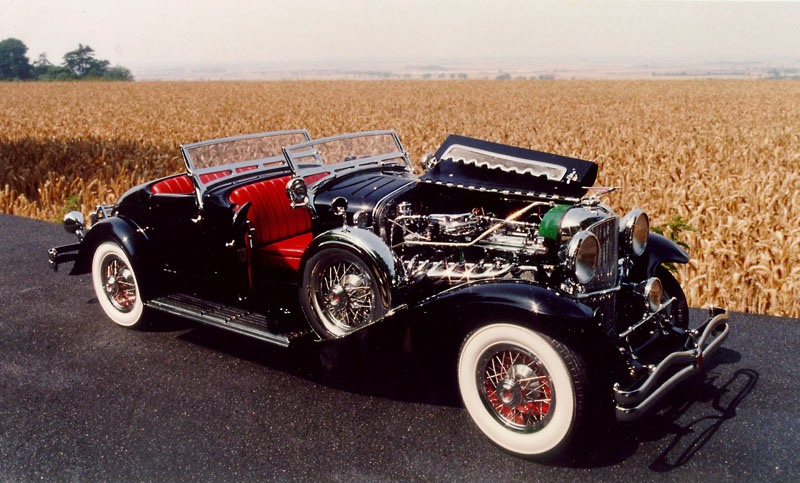

Construction of the Models

Starting out, each piece of a given model was handmade in metal or another appropriate material, based on the plans and photos. Copper, brass, nickel silver, and aluminum were all used. When necessary, parts were machined on a lathe or mill. Fenders and shaped parts might be hand-formed from brass sheet. They could also be made from copper sheet pounded over steel or carved wooden forms. Tires were molded from silicon rubber.

Frames were made up of machined brass pieces, and then silver soldered together. Major engine parts were cast in metal, starting with hand-carved patterns. The Wingrove’s documented the construction of their models in painstaking detail so that everyone could see the work that goes into building replicas with this level of expertise.

Awards and Honors

It goes without saying that Gerald Wingrove has been honored for his work as a model engineer. In July, 2000, Mr. Wingrove was awarded the honor of Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE). He received his award from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in the State Ballroom at Buckingham Palace. Photos of this event can be seen on his web site. Gerald was honored for his craftsmanship and “service to Model Engineering.”

In January, 2005, Gerald was selected by the Joe Martin Foundation to receive the Craftsman of the Year Award. Mr. Wingrove was the 9th person to win the award, which included a plaque and a check for $1,000.00. Although unable to attend the NAMES Expo in Detroit, Gerald and Phyllis were able to visit the Craftsmanship Museum later that year so he could be recognized in person. Gerald also kindly donated a number of signed copies of his latest book to be used as prizes in the Sherline Machinist’s Challenge contest.

Now, Joe Martin selected Mr. Wingrove for this award for several reasons. Chief among them is the number of unique skills and techniques that had to be developed in order to make the many parts for his models. From metal forming to casting, or molding rubber tires and replicating interior materials—everything had to be right for the car to look authentic. Additionally, before the building process even started, Gerald and Phyllis spent hundreds of hours researching the cars and making detailed dimensional drawings.

Over the years, Gerald also took the time to photograph and document his work in the form of many books. His tireless efforts allowed others to become both inspired and informed in the art of model making. Gerald’s body of work leaves behind a detailed record of some of the world’s most significant cars. It also leaves a legacy of quality model engineering that has served as a benchmark for future modelers.

On March 1, 2005 Phyllis and Gerald Wingrove stopped off in California to meet Joe Martin and receive the 2005 Craftsman of the Year Award. They were on their way to Hawaii to measure a vintage 4-masted steel sailing ship called, “The Falls of Clyde.” The Wingroves wanted to draw plans, and make an all-metal model of the ship. Though retired from model making as a career at this point, they continued to pursue projects that interested them.

Books by Gerald and Phyllis Wingrove

Although this list doesn’t cover every book or plan that the Wingrove’s compiled and disseminated, the following texts are some of the most comprehesive. While some of the publishers are no longer in businesss, many of these books cans still be purchased online.

The Art of the Automobile in Miniature: The Works of Gerald and Phyllis Wingrove—Model Engineers, by Gerald Wingrove. Published in 2003 by Crowood Press Ltd., Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire SN8 2HR. ISBN: 978-1861266323.

The Techniques of Ship Modeling, by Gerald Wingrove. (With a foreword by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu.) Published in 1974 by Fountain Pr Ltd. Reprinted 1976 and 1981. Approximately 15,000 copies sold. ISBN: 978-0852423660.

Unimat Lathe Projects: A Beginners Guide to the Lathe and How to Make Ten Useful Tools, by Gerald Wingrove. Published in 1999 by New Cavendish Books. Approximately 10,000 English editions have been sold, along with 5,000 Dutch and 5,000 German editions. ISBN: 978-0904568202.

The Model Cars of Gerald Wingrove, by Gerald Wingrove. Published in 1979 by New Cavendish Books. Approximately 5,000 copies sold. ISBN: 978-0904568127.

The Complete Car Modeller 1, by Gerald Wingrove. Updated and reissued in 2004 by Crowood Press. Approximately 8,000 sold. ISBN: 978-1861266446.

The Complete Car Modeller 2, by Gerald Wingrove. (With a foreword by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu.) Updated and reissued in 2005 by Crowood Press. Approximately 8,000 sold. ISBN: 978-1861267504.

*The Complete Car Modeller 1 and 2 have also been reprinted in paperback.

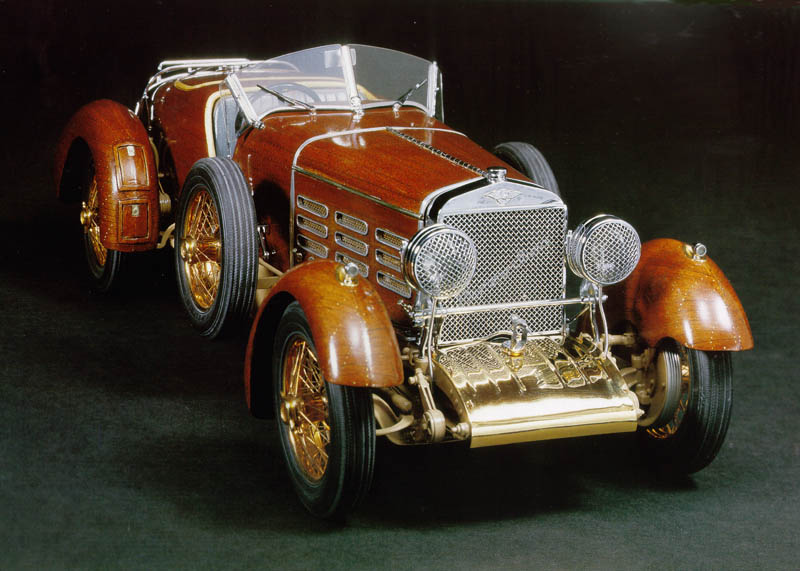

This 1924 Hispano Suiza H6C presented a unique challenge in model construction—namely because of its wood-planked body and full wood “pontoon” fenders. The tight grained pear wood on the model faithfully represents the original Honduras mahogany. Over 13,000 brass pins, each .012″ in diameter, were installed to represent the original brass rivets.

Unfortunately, we regret to inform that Both Phyllis and Gerald Wingrove have passed away (in 2018 and 2019 respectively). The Wingrove’s have made a lasting impression on the model making world, not only with Gerald’s incredible models, but also through the pair’s dual commitment to sharing their expertise. Gerald built approximately 220 automobile models during his long career as a master model maker. Many of them now reside in private collections and museums. We thank the Wingrove’s for their enduring contributions to miniature craftsmanship.

View more photos of Gerald and Phyllis Wingrove’s world-renowned model automobiles.