10/30/1885—6/8/1973

Whittling Doesn’t Begin to Describe This Level of Wood Carving

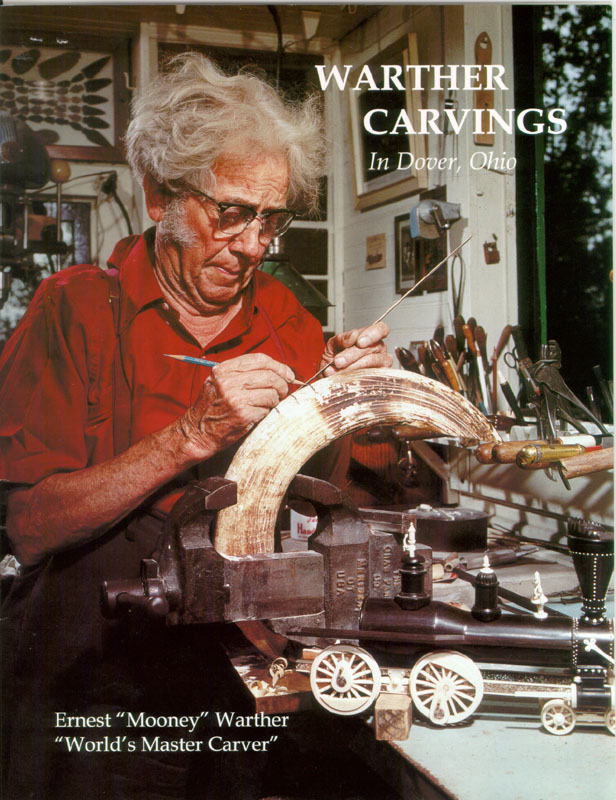

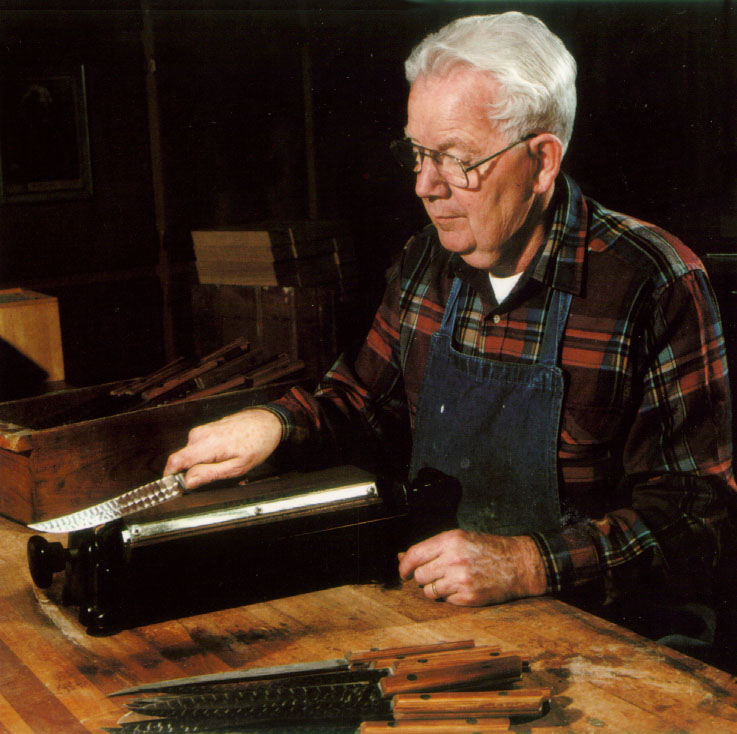

Ernest “Mooney” Warther is shown marking out a piece of ivory before carving his next part. This photo is from the cover of a book offered by the Warther Museum. The book covers the highlights of Ernest’s career, and features many photos of his work. (All photos courtesy of the Warther Museum.)

Introduction

Ernest Warther wasn’t satisfied with the quality of knives he could buy, so, in 1902 he started making his own. Over a century later, Warther Cutlery is now a third generation company being run by Ernest’s grandchildren. However, Ernest became even better known for his skills using knives to hand carve wood and ivory objects. The Warther Museum and Gardens, as well as the Warther Cutlery Company are located in Dover, Ohio.

How Ernest Got His Nickname, and His Start in Carving

Ernest “Mooney” Warther was born in Dover, Ohio on October 30, 1885 to Swiss immigrants. His father died when Mooney was just three years old, and his mother struggled to keep the family together by taking jobs washing, ironing, mending, and housing boarders. Because of the pressing economic conditions, Ernest was only able to attend school through the second grade. It took him four years to get through two grades, because he would only go to school when the weather was too bad to take the cows to pasture.

Calling on his Swiss heritage, Ernest went to work as a herdsman. At the time, everyone had a family cow or two for milk. Those who lived in town had to arrange for a pasture, and this was the basis for Ernest’s business. For a penny a day, he would take cattle from Dover to pasture in outlying areas, returning them at nightfall.

This was when Ernest acquired his nickname, “Mooney.” The name came from a Swiss word meaning “bull of the herd.” It foretold of the vibrant life force that Mooney would exhibit throughout the rest of his days. In fact, he became so well known by this name that few people outside his family knew his real name.

On one of Mooney’s daily treks to pasture, he happened to find a penknife on the road. Little did he know that this knife would become the instrument of his greatness. Mooney took up whittling, which passed the time admirably. His carvings during this period were rustic in style: caged balls, chains carved from one piece of wood, canes and pliers.

At one point, a hobo carved him a pair of wooden pliers. Mooney took it home, studied it, and then mastered how to carve his own pliers. These pliers became his calling card. It is estimated that Mooney carved about 750,000 pliers in his lifetime. At the age of 14, he quit herding cows and got a job as a scrap bundler in the local steel mill. Mooney spent the next 23 years working there.

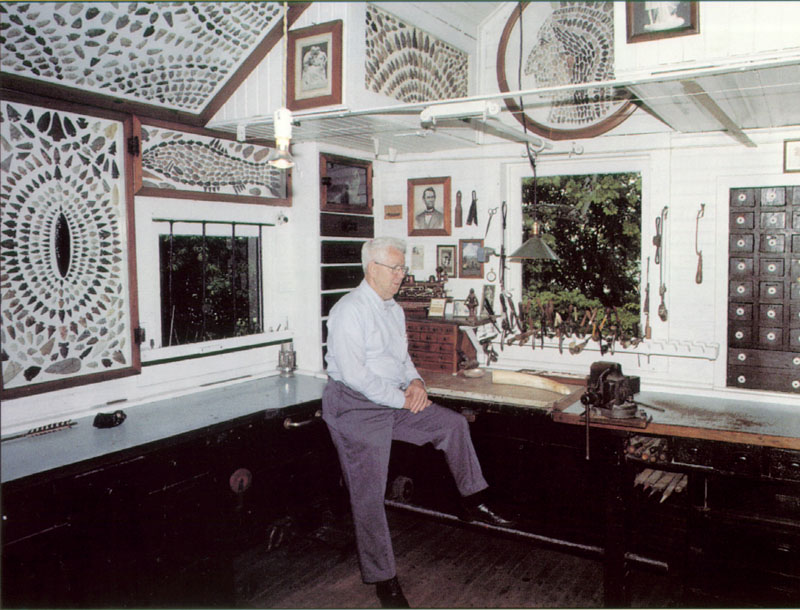

It was with the building of his workshop, at age 28, that Mooney, in his own words, “stopped whittling and started carving.” Thus began the great work of his life, carving the history of the steam engine. Mooney felt that his early carvings, such as pliers and canes, were mere whittling. His steam engines were carvings.

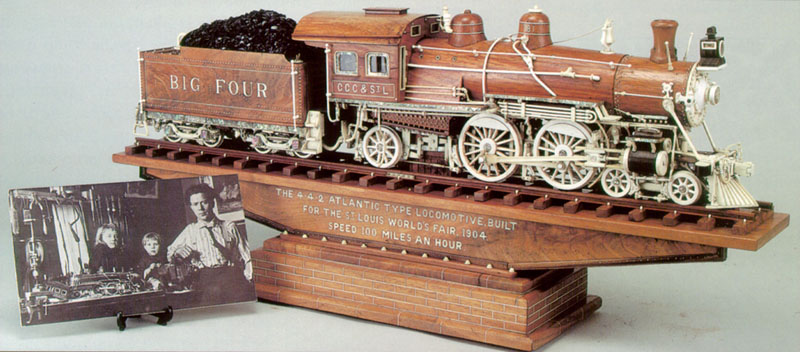

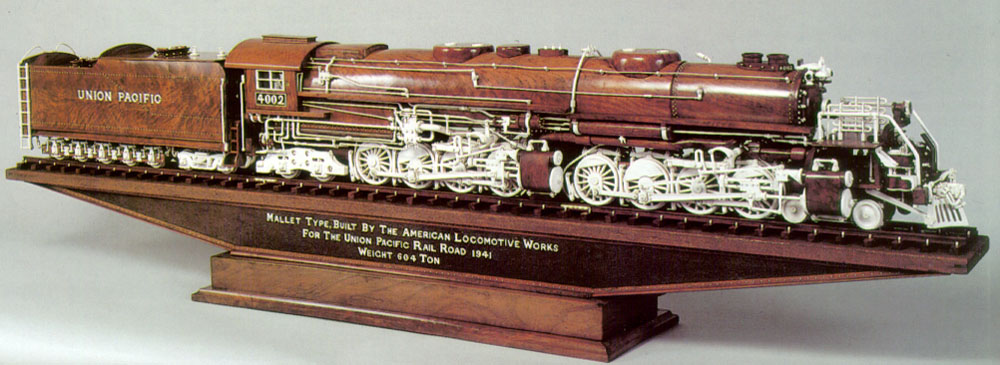

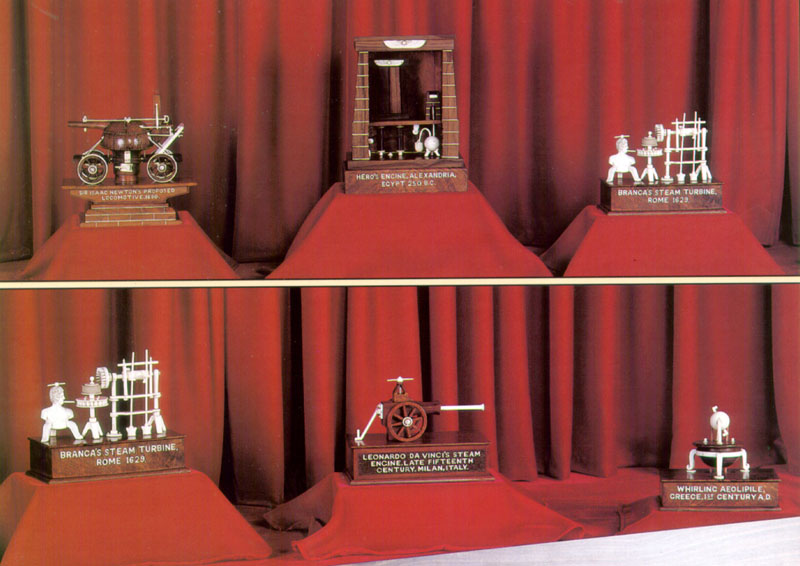

Mooney thought that the steam engine was one of the most wonderful inventions of all time. They had done more to advance civilization than any form of transportation to his time. Mooney’s hand-crafted works of art depict the evolution of the steam engine through 64 carvings. The timeline starts in 250 BC with Hero’s Engine, and ends with the Union Pacific Big Boy Locomotive of 1941.

At the age of 28, Mooney Warther built this little workshop. It was at this point that Mooney said he, “Stopped whittling and started carving.” The original 8’ x 10’ shop is now incorporated into a larger building. Note the arrowhead collections on the walls. (Photos courtesy of the Warther Museum.)

Now, Mooney’s first fifteen carvings were made from bone and walnut. In 1923, he was able to purchase ivory. On fourteen of his original pieces, he re-carved the bone portions out of ivory. From then on, Mooney carved walnut, ivory and ebony. For the last ten years of his life, he carved only in ivory.

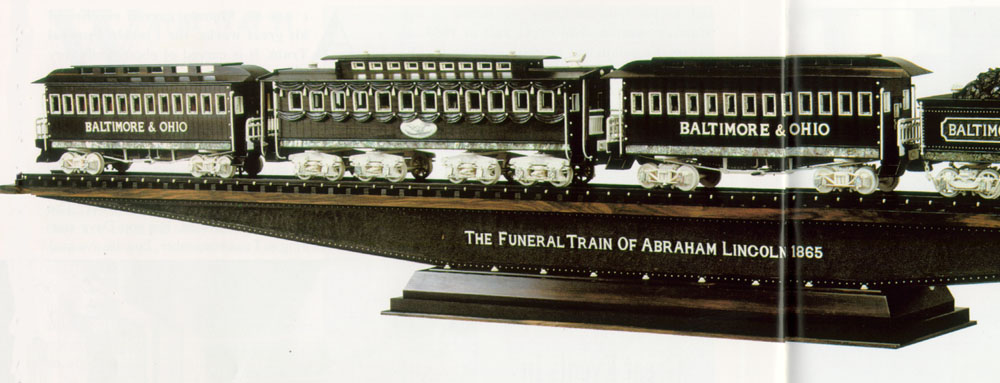

Interestingly, Mooney’s first sources of ivory were from cracked billiard balls. Later, he was able to purchase elephant tusks. On the Lincoln Funeral Train, he used the eyetooth of the hippopotamus, which was considered the finest grade of ivory.

For the first 23 years of his working life, Mooney was employed at the local steel mill. Starting in 1899, at age 14, he began at the American Sheet & Tin Plate Company as a scrap bundler. He would eventually work his way up to the job of head shearsman.

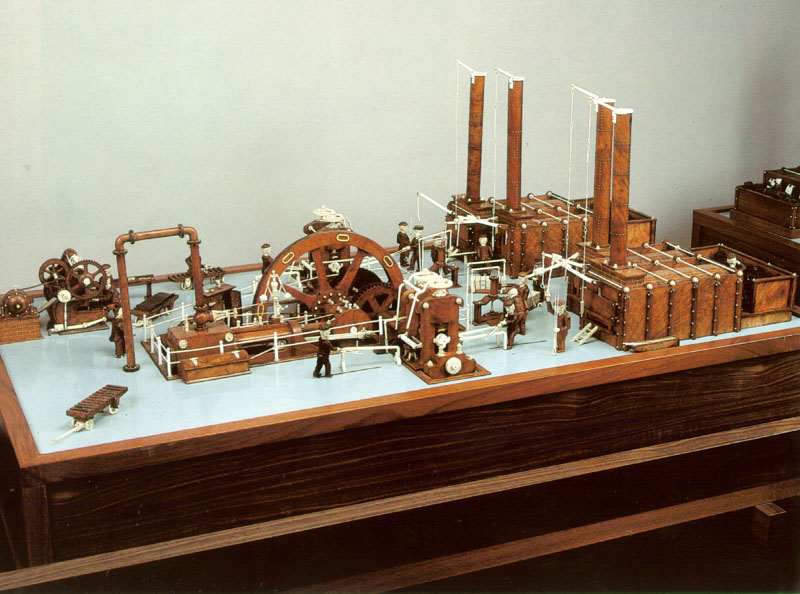

During that time, Mooney carved out 25 works of art. He would later carve a mechanized model of the steel mill out of ivory and walnut. Around the same time, he also learned to forge and temper steel from the neighborhood blacksmith.

The Union Pacific Big Boy locomotive was the largest of the steamers. Mooney carved his version from burled walnut and ivory, from January 19 to October 30, 1953. He completed the carving on his 68th birthday. The locomotive consists of over 7,000 individually carved pieces. As with all of Mooney’s carvings, the Big Boy is mechanically accurate, and carved to a scale of 1/2 inch : 1 foot. The wheels, pistons, flyrods, driving arms, and valves all operate just like the actual steamer. Even the bell swings. The original locomotive weighed over 600 tons, had 6’ tall drive wheels, and burned 22 tons of coal per hour. There were 25 built in the 1940’s. They were used mostly west of the Mississippi River. These were the last steam engines built, and by far the largest.

Not finding the knives he needed to suit his carving needs, Mooney learned to make his own. He designed a knife that fit his hand well, and had a selection of replaceable blades about an inch long that locked into place. When his mother complained that she couldn’t keep her kitchen knives sharp, he made a small paring knife for her.

His mother’s friends admired it, and soon Mooney was making knives for them—along with pocket knives for their husbands. During extended shutdowns of the mill, he would make knives for income for the family. This marked the beginning of the Warther Kitchen Cutlery business, which is still run by the Warther family today.

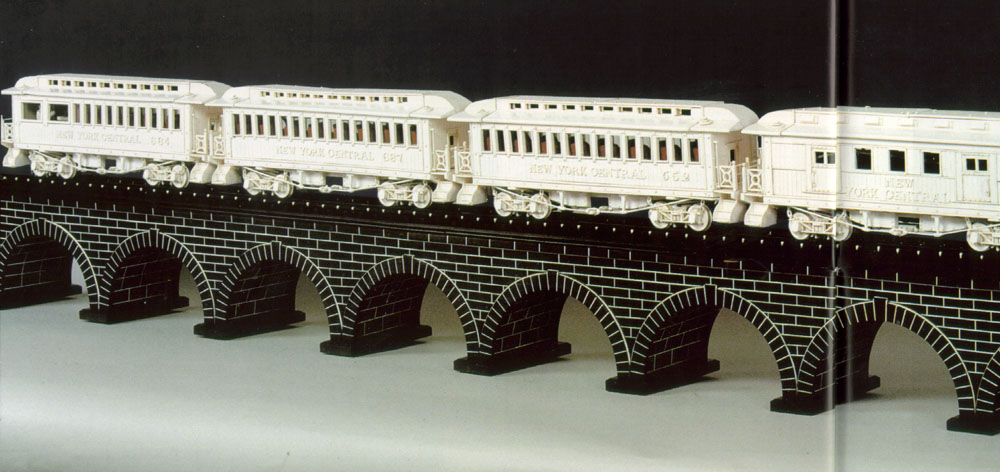

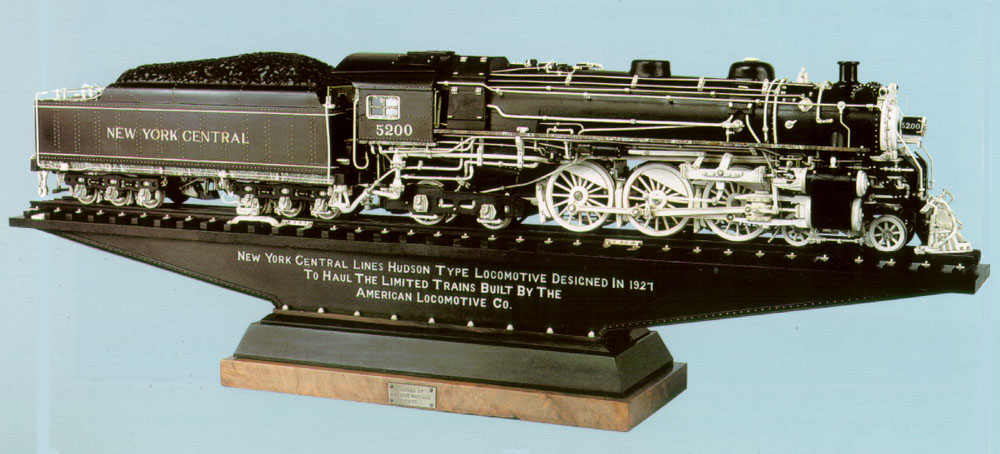

The 8-foot long Empire State Express was carved from ivory, while the stone arch bridge was made from blocks of ebony. The “mortar” is inlaid ivory. The photo from the Warther history booklet was too big for the scanner, so it’s published here in two sections. (As are several other carvings.)

Mooney is Discovered

In 1923, the New York Central Railroad heard about Mooney’s carvings, and made him an offer to exhibit his models on a special train. Mooney quit his job after 23 years at the mill, and toured the country displaying his carvings for six months. After that, he displayed them in Grand Central Station in New York City for another two and a half years. Mooney spoke about his carving and made souvenir pliers for show goers.

At the close of the show, the railroad offered Mooney $50.00 for his carvings, and $5,000 a year to remain with the display at the station—but he declined their offer. Mooney also received an even more handsome offer from Henry Ford, but turned that down, too. He replied, “My roof doesn’t leak, I’m not hungry and my wife has all her buttons.” (His wife was a collector of buttons, and her collection is also on display at the Warther Museum.)

After returning from his exhibit at Grand Central Station in 1926, Mooney decided not to go back to work at the steel mill. He felt that the old style hot rolling equipment would soon be out of date. (The plant closed for good in 1931.) Instead, Mooney decided to devote himself to carving. He and his wife, Frieda would make a living making and selling knives, and showing his carvings in a traveling show.

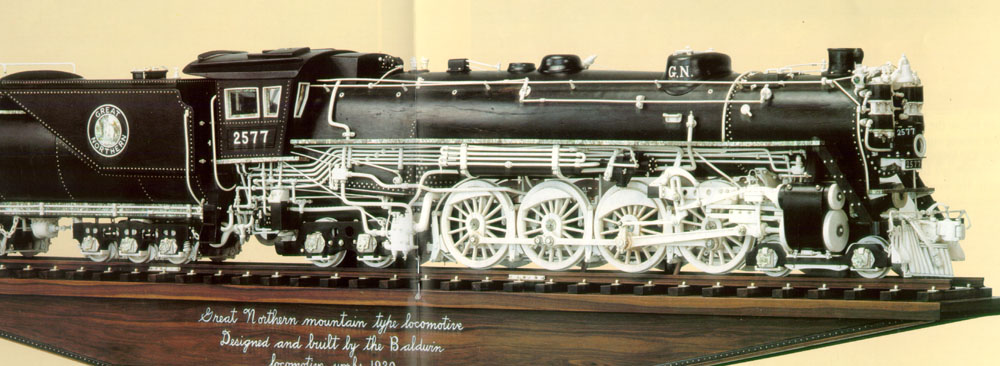

The stock market crash of 1929 was hard on everyone, including Mooney and his family. In 1933, he completed his finest work, the Great Northern Locomotive. Mooney continued to carve, make knives, and display his work in shows until 1936. At that time, he built a 12′ x 16′ brick building in the corner of Freida’s garden, which became the home for his carvings.

The carvings remained in that building until Mooney’s son, Dave bought a neighbor’s lot in 1963. Dave constructed a larger building adjoining the original workshop. This became the lobby to the Warther complex.

During WWII, Mooney took some time off from his carving. Through that time he exclusively made Commando Knives for local servicemen. Mooney made about 1,100 of these hand-forged knives, and they are said to have taken part in every major battle that the United States fought—with the exception of Pearl Harbor. Each knife was personalized with the serviceman’s name stamped into a brass plate in the cocobolo handle. Each also included a sheath of copper and stainless steel. Mooney had obtained all the inventory from the Canton Cutlery Co. in 1940, when they closed their doors. He used the steel from this inventory for his knives.

Since Mooney didn’t have a government contract, other necessary materials were hard to obtain. The community got together, and factory workers would bring scrap copper and brass to Mooney’s shop. He became known locally as the smallest defense plant in the nation.

Personally, he was strongly opposed to war, but felt that if the boys had to fight, they should have the best fighting knife he could make. When Mooney heard the announcement of the end of the war on the radio, he put down the commando knife he was working on and never finished it—nor did he ever make another. The unfinished Commando Knife remains in the museum today.

In 1953, at the age of 68, Mooney completed his 54th carving—the Union Pacific “Big Boy” locomotive. At the time, railroads were converting from steam to Diesel power. Mooney vowed that he would never carve a Diesel, even if he lived to be 1,000. He retired at the age of 68, and his son encouraged him to return to carving. At age 72, Mooney started his most extensive work, dubbed “Great Events in American Railroad History.”

These carvings included a solid ivory representation of the driving of the golden spike on the transcontinental railroad. Mooney also depicted the great locomotive chase of the Civil War, the Casey Jones locomotive, and the first passenger train—the John Bull. His largest project was the 8-foot long Empire State Express. At age 80, Mooney carved the Lincoln Funeral Train in ebony and ivory, with mother of pearl accents.

The Lincoln Funeral Train was completed on April 14, 1965—the 100th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination. The train was carved from ebony and ivory, with mother of pearl accents at the bottom of each car. A carving of Lincoln’s body rests in a casket in the center car.

With the construction of a new display building in 1963, Dave Warther was able to realize his dream of a display dedicated to his father’s work. Mooney continued to work on his Great Events series, carve pliers for visitors, and generally enjoy life. He died at the age of 87, leaving his last work, the Lady Baltimore locomotive, unfinished.

His son Dave stated, “As long as I can remember, Pop always said he wanted to leave a carving unfinished on the workbench. He believed everyone should do something creative, and should do it as long as they can.”

Selection and Use of Materials

Most of Mooney’s carvings started out with basic materials: an ebony or walnut log, an elephant tusk or ivory billiard balls, and abalone pearl. Warther lived in an era when elephants died of old age or disease, and less so from poachers. When he first started carving, Mooney used soup bones from his wife’s beef vegetable pot for the white trim on the carvings. Warther loved elephants, and the family today believes that he would have returned to using soup bones if he had lived long enough to see the devastation from poaching.

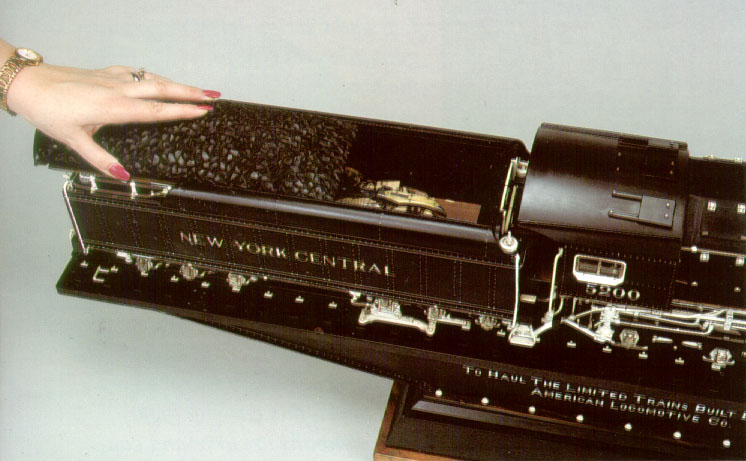

A top view of the tender for the New York Central Hudson reveals a secret compartment hidden under the coal. In each tender, Mooney hid a time capsule with notes from the children when he finished each project, along with the last piece of sandpaper used for finishing. On the back of the sandpaper, Mooney wrote the start and completion date of the carving, the number of pieces, and the total number of hours it took to carve.

Model Railroader Magazine Features Mooney’s Locomotives

Mooney Warther took on the project of carving steam engines throughout history. Model Railroader magazine featured his work in 1970, when Mr. Warther was 84 years old. The article is in black and white, and we have provided scans of each page here: page 1, page 2, page 3, page 4, page 5. The article is copyrighted by Kalmach Publishing Co. 1970. It was reproduced with permission of Model Railroader Magazine—Russ Larson, Publisher. A collection of Mooney’s carvings are on display in the Warther Museum and Gardens in Dover, Ohio.

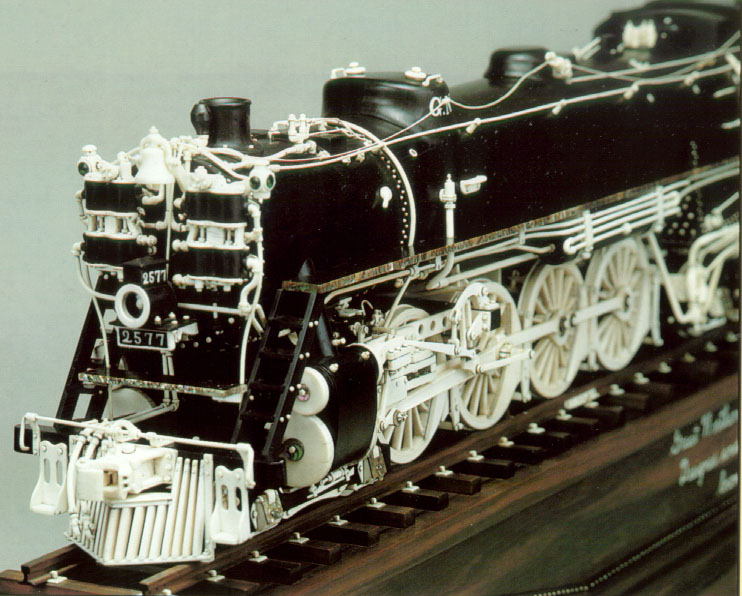

A front view of the Great Northern locomotive shows more detail in the driving wheels. Note the thin ivory bell chain looping down the top of the boiler.

Carving a “Plier Tree”

One of Mooney’s more unique carvings is pictured below this text. His round carved tower contains a “plier tree” which has 511 working pliers. The entire thing was carved from one block of wood. During Mooney’s cow herding days, a hobo showed him how to carve a pair of pliers from a solid piece of wood using only ten cuts. Mooney would then carve each handle into two more sets for a total of three. Then, he would carve each of the four handles into two more pliers, for a total of seven sets—all branching from the first.

In his twenties, Mooney took that progression to the unbelievable level seen in the photo below. This tree of pliers required 31,000 cuts, and took from June 24 to August 28, 1913 to complete. It was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. Professors at Case University studied the plier tree, and declared that someone would need an advanced mathematical education to design a block of wood in the correct shape to begin such a project. Mooney replied that he was glad he was told this after he made the tree, and not before.

Additionally, a book entitled, Mooney—The Life of the World’s Master Carver, was written by John P. Hayes. The 135-page book contains much more detailed information on Ernest Walther’s life and career. It also includes 14 black and white photos of Mooney, his family, and his work.

To learn more about Ernest “Mooney” Warther, visit the Warther Museum website.

Mooney Warther’s son, Dave, continued to run the family cutlery business and the museum. The knife making business is still run by the next generation of Warthers, maintaining the high level of quality that Mooney instilled from the start. The knives are handmade from high carbon steel, and finished with their trademark “engine turned” finish. Each blade is hand ground and honed.