1906—December, 1981

Founder of L.M. Cox Manufacturing Co. Inc.

This page is based on a more detailed biography from the Academy of Model Aeronautics website, written by Evan T. Towne.

Bringing Powered Model Cars and Airplanes to Millions of Enthusiasts

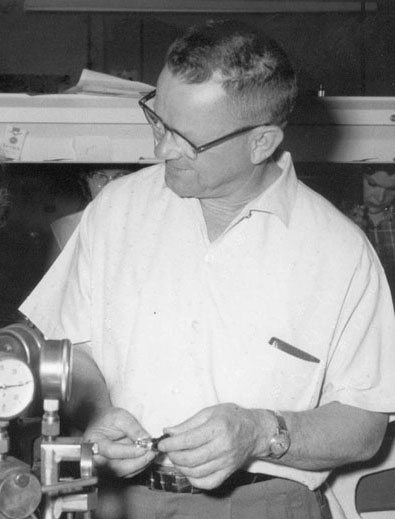

Growing up, Leroy Cox developed an early interest in mechanical devices while working around his father’s bicycle shop in Placentia, CA. Once out of school, he spent 20 years as an electrician, running his own electrical business part-time. Later on, efforts to branch out into a photography equipment business were unsuccessful due to material shortages caused by World War II.

In 1944, Leroy came up with a superior design for a wooden popgun, and produced it on a small budget in his garage. He employed some neighborhood women as the workforce, and put an initial investment of $2200 into the project. Like some of his later products, the popgun’s success was based on the fact that it was better built than the existing competition. Sales took off rapidly, and the product was a success.

However, the renewed availability of metal for toys at the end of the war meant that wooden toys would soon be a thing of the past. Cox recognized this, and along with his friend Mark Mier, the pair came up with a design for a metal model racecar. They aimed to take advantage of post-war America’s fascination with cars. By August 6th of 1946, Leroy and a crew of 20 people were turning out 1500 unpowered model cars a day!

Unfortunately, a devastating fire totally destroyed the factory on August 7, and brought an end to production after just 4 months. The destruction was almost total, and there was no insurance. However, they still had some orders on hand. So Leroy did some fast talking and bought a nearby vacant lot. A military-type Quonset hut was set up in 4 days! By October 15th, Leroy was back in business filling orders for Christmas. He even managed to double his production capacity despite the emergency change.

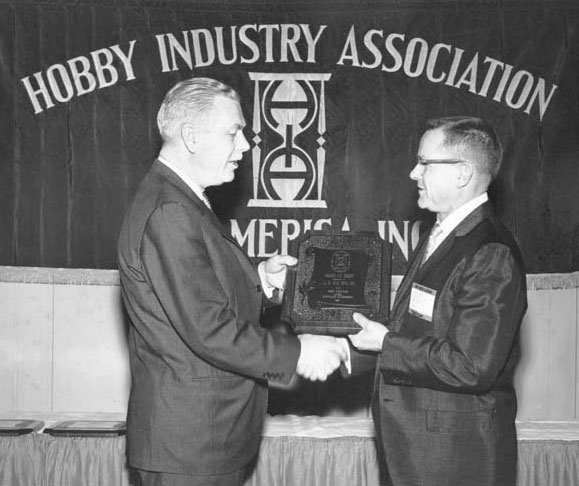

Leroy Cox (right) receiving an award from the Hobby Industry Association. Photo courtesy of Pegasus Hobbies archives.

In short time, Leroy introduced the Cox Thimble Drome Champion racecar in 1947. This model was not a pull toy. However, it included a handle and cord that attached to the side so it could be swung in circles at high speeds. The 9-1/2” long metal car had rubber tires and an attractive paint job, adding to its success. The car, which sold for $4.95, ushered in the start of the popular fad of tether car racing. The Thimble Drome name would soon be applied to future products as well.

Now, Cox noticed that customers who were fascinated with the realism of the Champion racecar were installing engines from model aircraft in them. So he contracted with Cameron Brothers model engine company for a .25 cubic inch engine, which could be installed in the Champion using a direct drive. The confined cockpit area dictated vertical cooling fins rather than horizontal—as was the convention. A later engine called the Doodle-Bug was similar, but smaller. It had a displacement of .099 cubic inches, and a larger .19” engine was also developed.

By 1948, Leroy was ready to introduce a groundbreaking engine-powered racecar. It was the first available for under $100, and it was considerably lower than that—at only $19.95. Sales that year surpassed $500,000 for cars with and without engines. Additionally, Leroy also developed and sold his own brand of Thimble Drome racing fuel.

Later in 1949, the company added a smaller car called the Special. Its .045 cubic inch engine was made up from a piston, rod, cylinder, and head from the Mel Anderson Company. However, they were produced in Leroy’s own factory so he could have better quality control. Other engine manufacturers at the time were experiencing quality problems, because often they could not afford to produce all of the parts themselves. They would outsource production of certain parts to others, and then do the final fitting and assembly themselves.

Cox recognized that in order to get the high quality production and consistency that he wanted, he would have to control all production himself. Leroy even designed the manufacturing equipment needed to do so. Eventually, the entire racecar and engine were made within his own facility. Although, he later outsourced production of plastic parts for some products. The year 1949 marked a rapid decline in the popularity of tether cars, but engines were still in demand in the rapidly growing model airplane market. Cox spent that next year working on an engine that would overcome some common problems (hard starting, lack of dependability) that plagued existing engines.

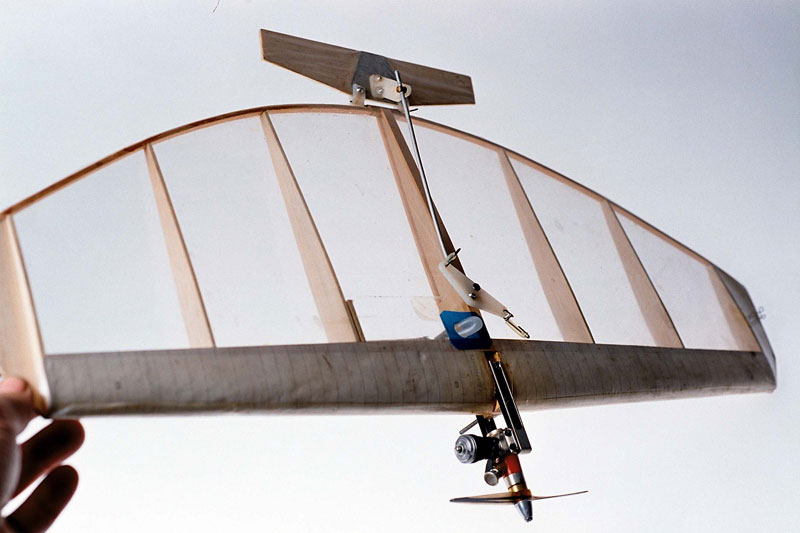

Paul Cords contributed this photo of a Cox P-51. It showcases the scale realism typical of the .049-powered aircraft models from Cox.

Ultimately, Leroy felt that a better running, easy to start, high quality engine would attract many more people to model cars and airplanes. So eventually he came up with a .049 cubic inch glow engine called the Thimble Drome Space Bug. This hit the market around October, 1950. The Space Bug engine featured a glow head, with a built-in coil of Cox’s own design.

However, the main advance came with the steel piston and cylinder—which were machined to very close tolerances for the time. The compact crankcase was cast aluminum, and attached to a large cast aluminum gas tank. This was mounted to the firewall with four screws. Inside the tank was a Reed valve fuel induction system. The Space Bug sold for just $6.95.

Additionally, this engine was available with the heavy tank removed—rebranded as the Thermal Hopper. That version also sold for $6.95. The Space Bug Junior featured a plastic tank, and sold for $3.95. The new products, and a timely 1953 engine review in Model Airplane News magazine, sparked a new wave of enthusiasts.

With racer production underway, Cox developed their first complete airplane in 1953. The Thimble Drome TD-1 was a U-control model weighing 10 ounces. It had aluminum wings that were 24-1/2” long. The plastic body was 18” long, and it sold for $19.95—ready to fly. The model included an accessory kit with a Skyon control reel, battery wires, connecting clip, control lines, filler hose, and finger guard.

Shortly into production, the TD-1 was already winning almost all of the 1/2-A flying contests. Around the same time, a new factory was built in Santa Ana, CA, where 250 people were employed. In 1955, Cox Manufacturing introduced their second generation .049” engine, which was called the Babe Bee.

This new engine featured a spun aluminum tank, and a signature black glow head and cylinder. The engine initially sold for $3.98, but was also sold mounted in different plastic U-control planes. It had a spring starter, making it easy for any novice to start properly.

Here you can see some of the production area at the Cox factory. Photo courtesy of Pegasus Hobbies archives.

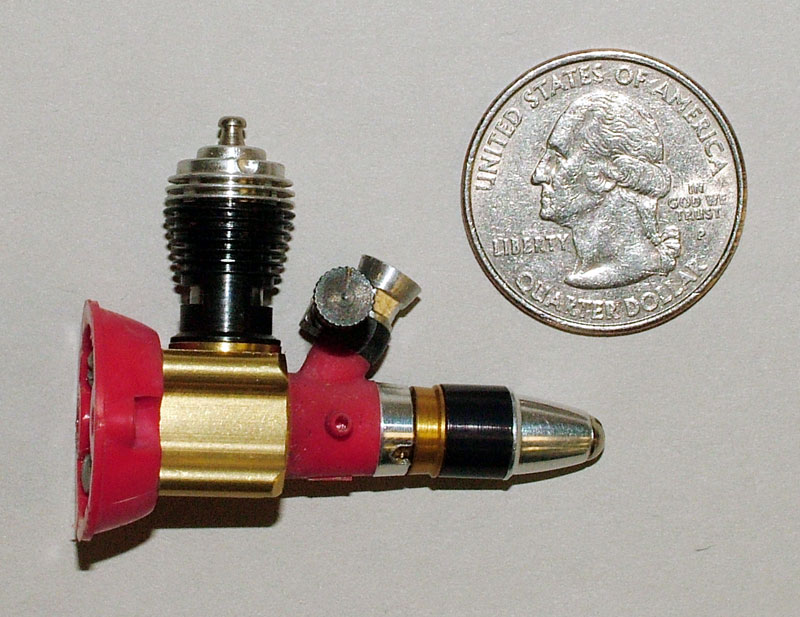

With the success of the Babe Bee, Leroy later introduced the Pee Wee. This was an exact scaled down copy of the Babe Bee, displacing .020 cubic inches. Interestingly, despite the smaller size it still put out almost as much power as the larger counterpart. It was billed as, “The World’s Smallest Model Engine” and sold for $3.98. These two engines were to remain in continuous production for well over 50 years—a remarkable achievement in itself!

In 1961, Cox took the Reed valve sport engine line and expanded it to include contest and high performance engines. They had engine designer Bill Atwood come up with a front rotary valve induction system that increased rpm, and resulted in what was called the Space Hopper*. This new method was applied to four engines in a 1961 release: the .010, .020, .049 and .15 cubic inch models. *Bob Beecroft noted, “The front rotary induction engines were the Tee Dee series.”

For the .010 engine, there was no fuel tank, so it could be used with light, thin-wall brass tanks. It could turn up to 30,000 rpm, and sold for $7.98. (It was sometimes offered with a brass tie clip, in case the user wanted to wear it to work instead of using it to power an airplane. This was a testament to its tiny size!) The .020 sold for $6.98, the .049 for $7.98, and the .15 for $12.98. These engines have sold in huge numbers, and brought the company a lot of financial success.

As time went on, the slot car fad did not go unnoticed by Leroy Cox. In 1962, they established Cox International in Hong Kong to meet this demand. However, the sudden collapse of the slot car fad in 1967 left the company with a cash flow problem. At this same time, Roy’s wife passed away, and he was experiencing health problems himself. So he sold the company in 1969 to Leisure Dynamics, Inc. They would continue production of the engines until that company was purchased again by Estes/Centuri in 1996. Estes/Centuri celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2005.

Unfortunately, Leroy Cox passed away in December of 1981. Over the years, his company produced so many engines (sometimes over 1 million a year) that it’s said their total output exceeded that of all model engine manufacturers in the world—combined! That is quite a remarkable achievement, and many modelers got their start with Mr. Cox’s products.

The Cox Tee Dee .051 was made in 1961, and was basically an .049 with a slightly longer stroke. (Bore: 0.410″, Stroke: 0.386”). The packaging refers to it as a front rotary valve contest engine.

Marketing Success

Early Disneyland visitors during the late 1950’s may remember the flying circle near Tomorrowland, where young pilots gave demonstrations of U-control aircraft. On an hourly basis, these pilots would do some fancy flying while teaching others how to fly, too. Leroy Cox managed quite an advertising coup when he got his own aircraft and employees chosen for these demos. They were seen by hundreds of thousands of visitors at the popular amusement park.

The “Flight Circle” had initially been manned by flying club members, and then by the Wen-Mac company. But Cox’s reputation as a more reliable manufacturer got them into that premium space starting in the summer of 1958. They would continue to operate there until it closed in 1965. The young flyers would sometimes fly two or three aircraft at a time, or bring people in from the crowd to try their hand at flying Cox aircraft. Tether cars ran in circles, and powered boats also ran in a pond. Read more about the Flight Circle at Disneyland.

Along with his ability to lead the company, Leroy was also well attuned to what the public wanted. He was always ready with the right product at the right time in history. However, the basis of his success with each product was always rooted in quality. His engines were successful because he insisted on standards of production excellence not previously achieved by other manufacturers. He was able to maintain this standard despite the large number of engines he produced. Leroy developed his own manufacturing and testing equipment to achieve this level of excellence. It’s claimed that piston/cylinder tolerances of over 25 millionths of an inch (0.0000025”) would result in rejection!

Additionally, Leroy Cox was also one of the first hobby manufacturers to exhibit at the Nuremberg Toy Fair, and the first American company to have a booth there. This gave his company worldwide exposure, and resulted in the export of his engines to over 50 countries.

This photo shows Lee Heinly, one of the Cox pilots, at the Flight Circle following their last show. Behind him is the model boat pond. Photo courtesy of davelandweb.com.

More Information on Cox Products and History

See a more complete discussion of the development and specifications for various cox engines. This includes diagrams of how the engines work, and photos of the various glow heads.

Additionally, read more about the Cox Museum. This German site has quite a collection of Cox specs and details. It’s probably the most complete source available on Cox products and history.

Read an article about Leroy Cox from Mechanix Illustrated, November, 1958.

View more photos and descriptions of Leroy Cox’s groundbreaking engines and models.

“I hadn’t realized it was Bill Seltzer who came up with the machined bar stock concept to replace earlier castings. Man, he was there a very long time! I met him in 1995, when Cox agreed to manufacture the Medallion .051 specially for the NFFS (National Free flight Society). We made a contract that was sealed on nothing more than a handshake, and the motors were made. It’s really a shame that they are now gone.”

—Bob Beecroft.