April 16, 1929—February 10, 2012

Fulfilling a Lifetime Goal by Building His Own Scale Steam Crane

Introduction—Jerry Brown’s Model Steam Crane

By Craig Libuse

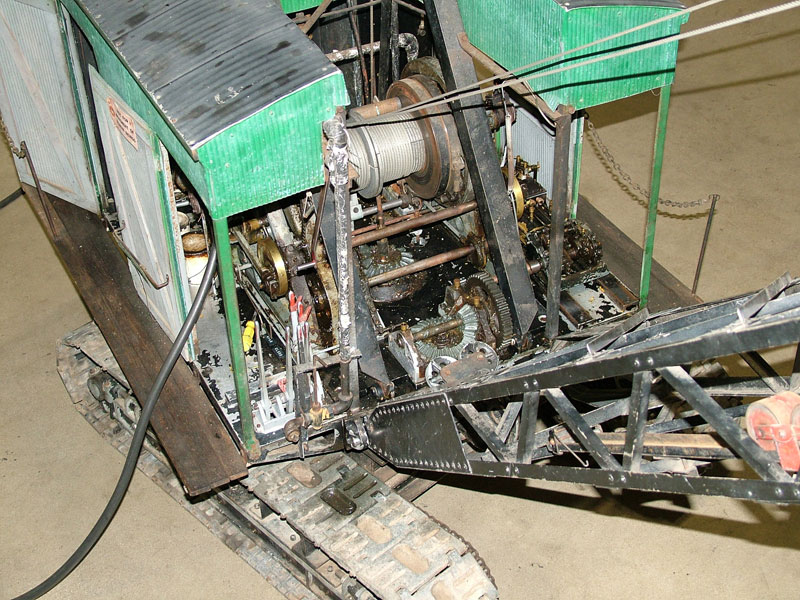

In 2005, many spectators, including myself, were treated to seeing Jerry Brown’s steam crane in action at the Men, Metal and Machines show in Visalia, CA. Restrictions on the use of live steam indoors meant that it was running on compressed air, but it was impressive to see nonetheless. The crane project was started in 1972, and first run in public in 1978. It took 1700 hours of work over the course of six years to complete. By 2005, the crane had been hard at work for 27 years, and it had the look of a real working machine. Unlike the pristine display engines usually seen at model engineering shows, it was greasy, oily, and not disguised as anything but a machine intended to do heavy work. In actuality, Jerry does use the crane to dig “full-size” earth.

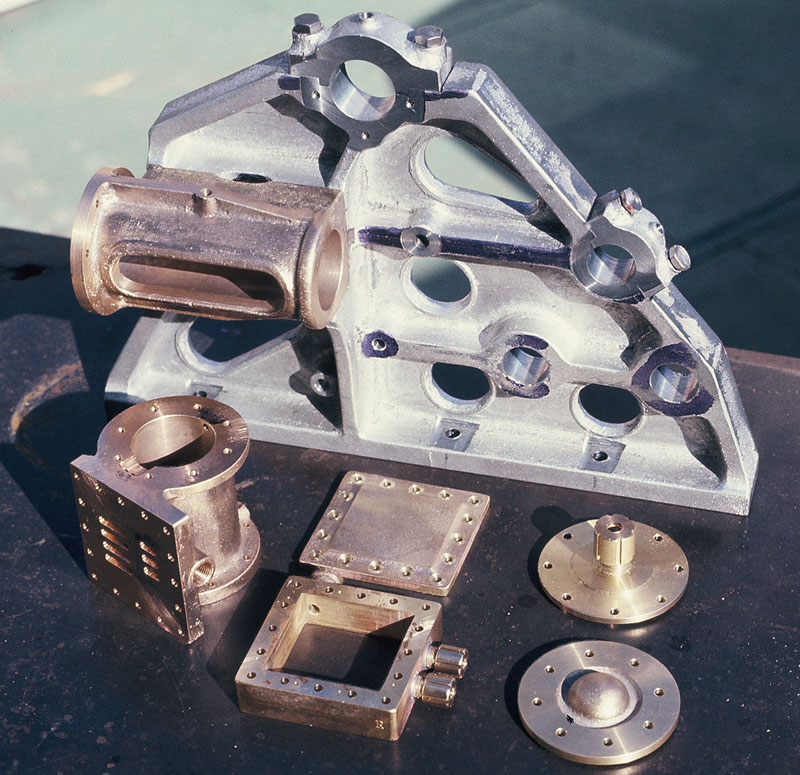

Below is an article which Jerry wrote for Australian Model Engineering magazine. The photos that accompany the article were taken during the construction of the project, when parts were freshly cast, machined, and painted. By contrast, the photos immediately below this writing (and elsewhere) show the crane after years of use. This is an example of good craftsmanship put to work, instead of being pampered.

The following is a little information from Jerry about how he came to work with metal. After that is the Australian Model Engineering magazine article where Jerry describes how and why the crane was built. It’s reproduced here with permission. Jerry’s experience is similar to many other stories of great model engineering accomplishment. He was always fascinated with the big machines, and knew he would never be able to own the real thing. So Jerry did the next best thing—he built himself a scaled-down working model instead.

Update: February, 2014. We recently received word that Jerry passed away in February, 2012. We confirmed with the executor of his estate that the steam crane featured here is now in storage. The executor hopes one day to prepare an operator’s manual for it and get it running again. Future display plans have not been confirmed.

These photos are from the 2005 Men, Metal and Machines model engineering show in Visalia, CA. Jerry is demonstrating the crane for a spectator. The second photo shows the crane in “operating” condition. An air line is used to power the crane, as show regulations prohibited the firing of a boiler inside the venue. (Photos courtesy of Craig Libuse)

The Making of a Model Engineer

By Jerry Brown (Submitted in 2009)

The hobby of building miniature functional models of full-size machines is known as model engineering. It likely originated in England, as did much of the machinery modeled. Quite fittingly there is an English magazine called Model Engineer that put out its first issue in 1898.

For as long as I can remember, this has been my main hobby. I’ve always been fascinated by large machinery. Of special interest are engines and earthmovers such as revolving power shovels. When I was growing up in the 1930’s, large industrial engines ran at speeds so slow I could count the exhaust beats. Many were steam (external combustion) and early gasoline or diesel (internal combustion) engines with exposed moving parts, which helped in understanding how they worked. Early on, I was building crude models from fruit crates, tin cans and whatever else I could scrounge, which was easy in those days. Now, even the trash is locked up.

I had no idea how to build miniature engines to run these things, so they were all hand-powered. In 1945, about halfway through high school, I built a lathe from scrap material. It was crude, but it could cut metal. I had learned basic foundry skills in the school shop, and had set up a small non-ferrous foundry in the family garage. This enabled me to build a small steam engine. It was patterned, from memory, after a toy (Weeden) engine I had years earlier. Not much, but it ran, and proved I could do it. I was on my way. Magazine articles kept up my interest, and a few years later I built a better lathe (which is still in use). The lathe and a drill press from a WW2 machine shop constituted my shop. (That old drill press is also still in use, and I wouldn’t trade it for any current import.)

A lifetime of various metalworking skills were needed to take on a project like this.

With these I built another engine, and this one could rightly claim the title of a miniature steam engine. I was hooked. After a hiatus for Army service, I made up for lost time with an intensive build-up of my shop. After acquiring a standard lathe and milling machine, I was ready for a serious project. My goal was to build, from scratch, an engine big enough to do useful work. Perusing old steam engineering books, I was able to design what I wanted—a 1.25″ bore x 2.25″ stroke engine similar to those that powered mills and factories in the 19th and early 20th centuries. I made wood patterns to form sand molds, and poured metal castings for the major parts.

After everything was assembled I tried a test run on compressed air. No problems, so next was a steam test (with borrowed steam at a club meet, since I had no boiler.) It ran fine, with no leaks, which an onlooker said was rare for a first-run on steam. I subsequently had a boiler built, and mounted it with the engine on skids for portability. After some 40 years, it’s still running as well as ever powering a grain mill which grinds corn for my pancakes. Fired with scrap wood (or corn cobs) it’s a big attraction at antique engine shows.

Despite these accomplishments, I still hadn’t fulfilled my childhood dream of building a steam-powered miniature revolving crane/excavator. These were all gone from the construction world in my time, except for some that survived into the 1970s as pile drivers, because their boilers could supply steam for the hammer. I always liked watching these things. If I were a musician I’d have to be a percussionist because, like the legendary John Henry, I love to hear that cold steel ring. In 1972, working for a company that made live-steam miniature railroad equipment, I figured the time had come and I’d best not wait any longer. The crane would be a vastly more complicated project than a plain stationary engine, but I plunged in, learning as I went.

It was a labor of love, culminating in 1978 with the first steam-up. Thirty years later it’s still going strong, digging in my garden and demonstrating at shows what steam power once did (like building the Panama Canal). Since schools are closing out shop courses, I hope it also shows that old technology is still viable, and that you don’t need a lot of formal education to make use of it. The first locomotive that came here from England arrived disassembled. The story goes that a village blacksmith (one of a now nearly vanished breed) with little theory, but lots of experience and intuition, could build or repair anything. He was chosen to put the locomotive together. He’d never even seen a steam engine, but assembled the parts into a working locomotive.

I like to think there may be a little of that old blacksmith in me, and that with my miniatures I’m helping to interest young people in this kind of creativity before it all goes across the pond to China. For if that happens, we may some day wish we had it back.

—Jerry Brown

Jerry’s 1/6 scale Crane digs up the earth.

A Miniature Live Steam Crane

By Jerry Brown

Photos by Jerry Brown and Bruce Ward. (Article published in March/April, 2008 issue of Australian Model Engineering magazine.)

My interest in power shovels and cranes goes back at least as far as I can remember. While more “normal” people were watching sports, I would be happier looking at these things. Their operators seemed no less skillful than ball players, and what they were doing seemed much more useful. Revolving shovels, with their various mechanisms working in concert, have a measure of balance and coordination matched by few other machines—a symphony of motion. When run by steam, with all its characteristic sights, sounds and smells, they take on added interest, almost seeming to come alive.

Ever since childhood days of building crude wood and tin-can toys, I had dreamed of building a genuine operational miniature, and since steam seemed the only practical self-contained power source that could be satisfactorily scaled down, there was no question about how it would be powered. But due to the usual interventions, those dreams were a long time materializing. By 1972 I had accumulated most of the equipment needed for such a project, realized I wasn’t getting any younger, and that I had better get started while such things could still be done.

As it turned out, that was a more timely decision than I knew. What I still lacked was know-how. I had built stationary engines, but this was obviously going to be far more complex. Port-reversing slide valves would be required as a convenience on the main engine and a necessity on the swing engine, and I hadn’t the foggiest idea how to make them. Then there would be all the gear ratios, power calculations, clearances, controls, etc. All kinds of information and parts are available for railroad models, but none for this sort of thing.

Faced with all that, plus the skepticism of some who learned what I had in mind (along with no small amount of my own), away I went. At this point I would like to gratefully acknowledge the help I received from fellow live steamers, without which the project may never have been completed, certainly not as successfully as it was. One fellow had a full-size Erie shovel; another was a collector who graciously loaned old parts books and drawings. That solved the valve problem plus many others.

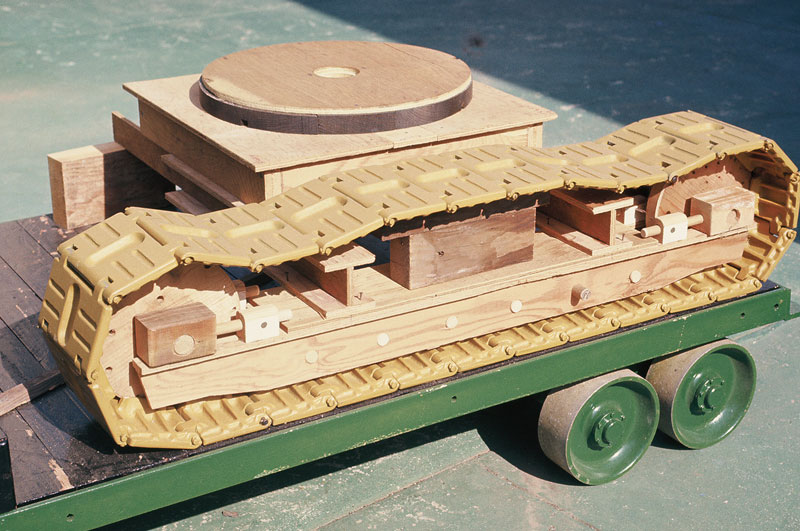

The first decision concerned size: How big should this thing be? I guessed that a 2 inch-per-foot scale (1/6 full-size) version of a 50-ton crane might be about right. From pictures I built a wood and cardboard mockup. I had guessed right—much bigger would be a transportation problem, and much smaller wouldn’t have the weight to dig very well in full-size earth. So with that, I set to work, learning as I went. What developed was a sort of composite of Bucyrus and Northwest, the makes I had most access to. Except for chains, most plumbing fittings and spur gearing, it is all scratch built. The caterpillar track base is 25 inches square, rope size is 1/8 inch 7 x 19 galvanized steel, and the working weight with heavy clamshell is nearly 600 pounds. Its stability was demonstrated when the clam picked up a 50-pound log, nearly a 100-pound total load, with the boom at about 45 degrees and no sign of tipping. Castings are mostly of zinc alloy and bronze, poured in my shop foundry.

All functions are steam operated. Boiler feed water is from three sources: injector, duplex steam pump, and a power pump run by the main engine. There are two double-cylinder engines, one powering all hoist and travel functions, and another (the swing, or slewing engine) for rotating the superstructure. I suspect the reason for a separate engine for this function, rather than a clutch system from the main engine as in more modern machines, was that it was simpler since the same engine was used for the crowding action on dipper shovels. In any case, it was an additional challenge, and adds more interest to the operation. One of the biggest thrills of the entire endeavor was the first test run of the main engine.

Going from drawings of the cored steam passages in the full-size to drilled ones on the model, I wasn’t sure I hadn’t gotten disoriented somewhere until I finally put air to it. With only one side assembled, less stuffing box packing and with the valve cam set by eyeball, I hesitantly opened the air valve. Much to my relief it ran beautifully in either direction.

The tracks are independently driven through jaw clutches for steering. The two hoist drum clutches are external bands worked by steam rams. The brake bands are direct mechanical with over center toggles. Both are operated by a complex system of links, bell-cranks and springs from the control station levers, a departure from full-size practice due to the operator being some six times too large to fit inside to use foot pedals. (The pedals ARE functional, though; they lock the levers in clutch position for powering down loads, useful in crane work). The boom hoist is a separate drum, worm-driven (and self-locking) from the main hoist gear. The boom is of riveted aluminum angle, 100-inch basic length with 20-inch optional section. Not really a “shovel” (I haven’t gotten around to building that attachment yet), it is a crane with heavy and light clamshells and a dragline bucket. Capacity is about 2 scale cubic yards (just under 2 gallons).

To check bucket geometry and operation, cardboard mockups were tested in sawdust. After finishing the clamshell I had to see what 45 pounds of bucket would do in real soil, so I hauled it out into the garden and hastily reeved it with some old sash cord. What it did (you guessed it!) was break the cord, but not before a quite respectable bite had been taken.

On to steam! The boiler is a conventional vertical fire-tube type, originally steel but now, due to corrosion and maintenance problems, copper. It’s big enough to make all the steam needed and is a good counterweight. I first tried firing with wood, but soon found it was a nearly full-time job. My first oil-firing attempt was with used engine oil. It was free and burned hot, but only after raising steam with a wood fire like the big ones did in the old days.

That problem was eliminated by changing to diesel fuel. I use a small spray-gun type atomizer, and when I get the feed pump at the right rate the boiler pretty much takes care of itself. In 1978 at the Fall Meet of the Los Angeles Live Steamers after six years and some 1700 hours of effort, most of it enjoyable, some of it challenging, and all of it interesting, the rig was fully operational. I bravely decided to test myself and the machinery by attempting to pick up an aluminum can with the clam. Considering the vagaries of the control system, distractions from the usual crowd of observers and my inexperience as a runner, I was sure the can would be crunched into a shapeless blob.

To my surprise and relief it wasn’t—it hardly suffered a dent. I’ve never worked up enough nerve to try it again, being content not to drop a load in the middle of a swing! Allowing for the physics of reduced size, it operates much like the full-size rigs, and it’s big enough to get into the same kind of trouble if the runner goofs. Fortunately, the troubles are easier to correct.

The size choice has proved to be ideal, and the non-standard control system, though inconvenient when raising suspended loads, has worked very well. (Never having run a full-size machine, I had nothing to unlearn.) Running the clam was no big deal, but the first time I tried the dragline I acquired an instant respect for the runners of the big ones. Why did I build it? Why does one swim the Channel or build a Brooklyn Bridge from toothpicks? In this case, as I say, it was a lifetime ambition.

I’ve always liked to watch the wheels go ‘round, especially when they’re steam powered. And maybe because this machinery is kind of a reminder of a time long-gone when some of our present problems hadn’t even been thought of. In any event, I’m glad I did it when I did. One thing I’ve learned is that if you want to do something, do it as soon as you can because you never know when it will be too late.

Watching the clam pull itself into the ground as the closing line snakes through all those sheaves to the sound of the engine and smell of steam and hot oil made it all worthwhile. Not to mention the amazement of spectators, most of whom never saw the big ones at work. And the small boy, growing up in the plastic, throw-away age asking sort of awe-struck, “Is that made out of metal?” Steam machinery buffs will understand.

Crane Specifications

-

Description: Steam Locomotive (self-propelled) Crane, Caterpillar Mounted Main Engine, 1-1/4 x 1-1/2″ double port-reversing slide valve type.

-

Max. Rpm: 500, Indicated HP: 0.7 @ 80 psi.

-

Estimated torque: 51 inch-pounds.

-

Swing/Crowd Engine: .75 x 1” double port-reversing type.

-

Hoist gear ratio: 7.38

-

Scale pull on main line: 116 lbs. (25000/216).

-

Main drum: 3” diameter x 3.5” long. Capacity: 17.25’ per layer of 1/8” rope.

-

Auxiliary drum: 3-12 x 2-1/4”, 12’ per layer.

-

For clamshell work, both drums are 3-1/2” dia. X 2.81”, 16.5’ per layer.

-

Drumshaft speed: 40 rpm.

-

Swing rpm: 4; Total gear ratio 86.4.

-

Boom hoist ratio (from crankshaft): 15.3.

-

Drum: 1-1/4 x 1-1/2” long.

-

Line speed: 8.3 fpm average.

-

Track base: 25 x 25”; Loading (at 600 lbs. total weight): 2.4 psi.

-

Maximum travel speed: 10 fpm.

-

Gear ratio bull wheel to crankshaft: 87.

-

Travel/rev. of bull wheel: 21-1/4”.

-

Weight with 100″ boom, 3 gallons of water, 1 gallon of fuel oil and steel boiler: 634 lbs. (less bucket) (determined by teeter-board/spring-balance method).

-

1/6 scale cubic yard = 216 cubic inches, or 0.94 gallon.

View more photos of the construction process, and Jerry’s finished live steam crane.