A Wide Variety of Steam and Gas Engines That Were Made to Run

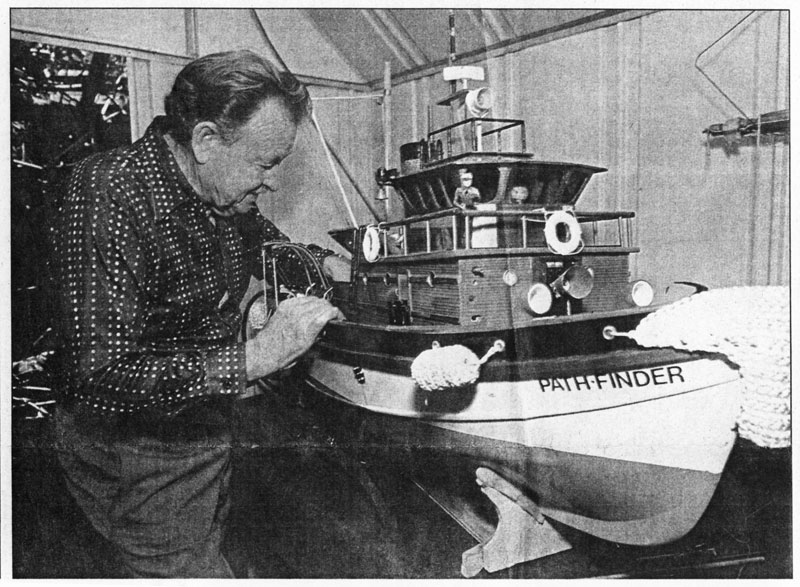

Clarry Dawson fine-tuning the steam engine in his tugboat “Pathfinder.” This photo was taken from an article about Clarry in the San Diego newspaper, the Blade-Tribune.

Mr. Clarence Dawson was known to his friends as “Clarry.” When he passed away in 2005, his daughter called the Joe Martin Foundation seeking advice on what to do with Clarry’s large collection of steam engines. Because Clarry lived near the museum, in Carlsbad, CA, we had the opportunity to document some of his work. Read on to learn more about the man responsible for this diverse collection of engines.

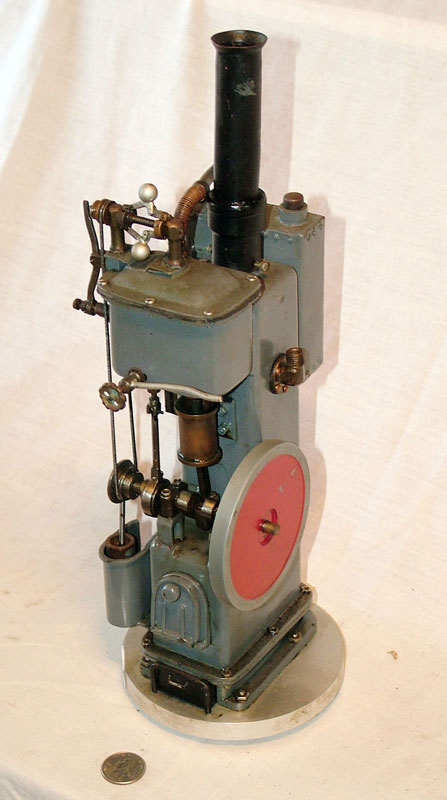

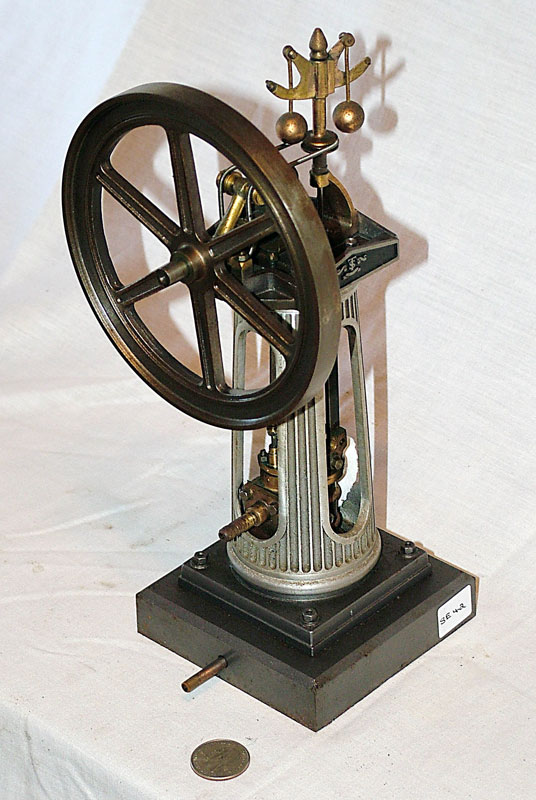

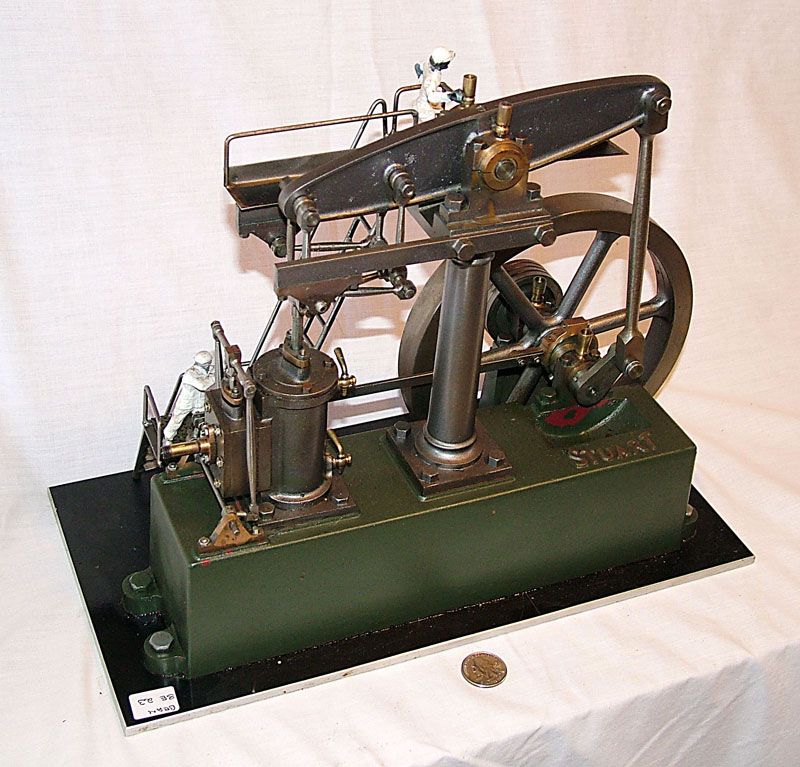

Detailers Versus Operators

Among model engineers, there are those whose primary concern is appearance, while others are strictly concerned with operation or function. Clarry Dawson was an operator, but he was also a clever and prolific craftsman in retirement.

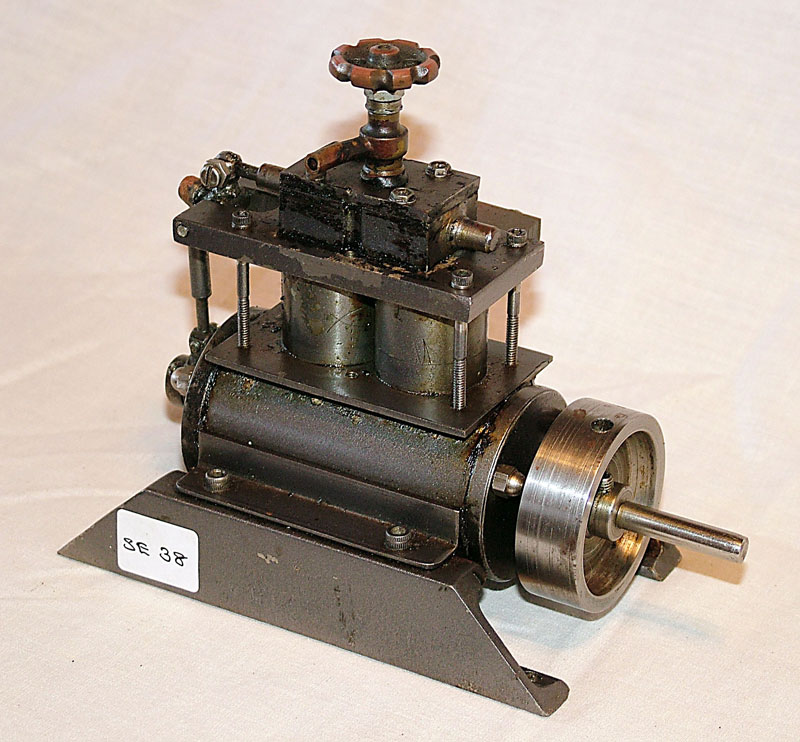

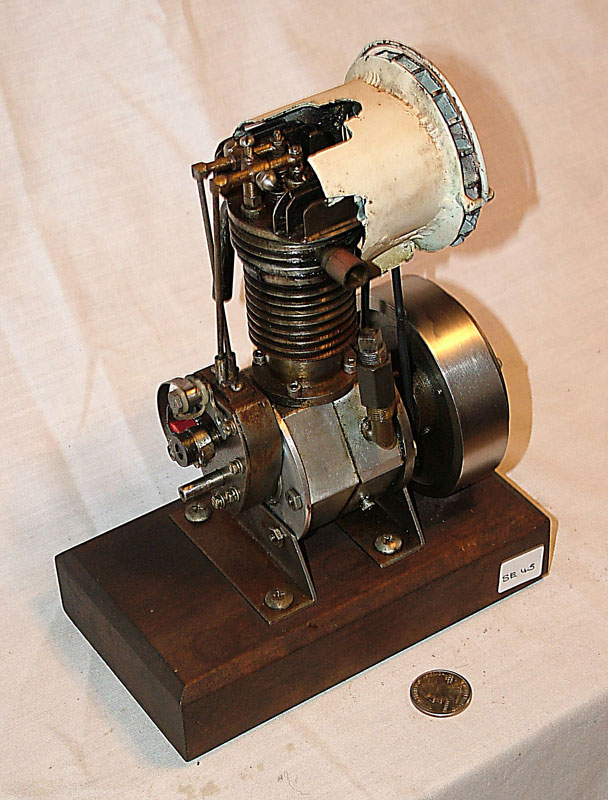

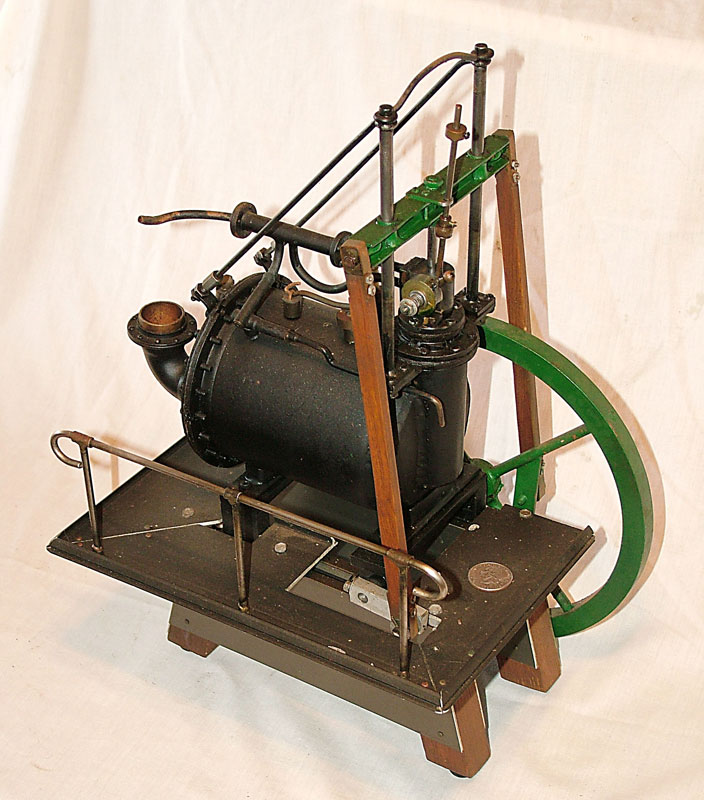

For Clarry, retirement meant continuing to work as he had, only this work would involve projects he was truly passionate about. In fact, his daily schedule simply changed from repairing other people’s cars, to making his own engines. The engines shown on this page represent a variety of types and configurations, showing that Clarry was always willing to take on a new challenge when it came to building engines.

From Australia to England, and Eventually the USA

Clarry Dawson was born in Australia, but moved to Kent, England at the age of ten. In Kent, Clarry loved to watch the steam trains that were then in service, transporting all kinds of goods. Jumping ahead, Clarry would later serve as a Flight Engineer in the Royal Air Force (RAF) during World War II.

The RAF provided him with most of his mechanical skills. After the war, Clarry took advantage of these skills by building custom vehicles once he moved back to Australia. However, he found it hard to make a living there. At the suggestion of an American friend, Clarry moved to Los Angeles in the 1960’s.

Once in LA, Clarry found the big city traffic intolerable, and was almost ready to return to Australia. However, he drove down to San Diego by chance, and found the coastal communities there to be more like his native Queensland. Leaving Australia behind, but retaining his native accent, Clarry decided to stay in the United States.

In 1967, Clarry started working for a body shop at an auto dealership in Encinitas. Three years later, he left the dealership and opened Dawson’s Body and Paint shop in Carlsbad. Clarry ran that business successfully for the next decade, and then retired.

Early Love of Steam Sparks a Retirement Hobby

Now, Clarry often remembered his youth in England, where he initially acquired a fondness for steam engines. Beyond just appearance, Clarry was also interested in them for the history they represented—namely, powering the Industrial Revolution. A few years before his retirement, Clarry started purchasing the machine tools he would need to build steam engines. By the time he retired, in 1975, he had a very well equipped home shop, ready for use. With more free time in retirement, and a lifetime of metalworking skills to rely on, Clarry was ready to do what he really wanted—build model steam engines.

Over the years, Clarry had collected many books and magazines full of photos and drawings of the engines he wanted to build. He usually spent about three months on each engine, working until it ran to his satisfaction. Once Clarry had an engine running well, he had achieved his goal, and was ready to move on to the next project.

However, some of these projects took up to nine months to build due to size, complications, or because Clarry was also building a boat or locomotive for the engine. Over the years, he built several large radio-controlled launches and tugs, as well as several steam locomotives. Through it all, Clarry still managed to turn out 20 models in a 5 year period. Ultimately, his collection would consist of more than 45 engines!

Though most of Clarry’s engines were tested and run using compressed air, his locomotives and boats were run on live steam. Fortunately for Clarry, his home in Carlsbad was located on a finger of water extending from the local lagoon. Because of this, he was able to run his boats right from a dock in his backyard, hoisting them into the water with a crane he built. Clarry also built a section of track that ran from inside his machine shed out into the backyard, which was used to test his locomotives.

Elegance in Steel

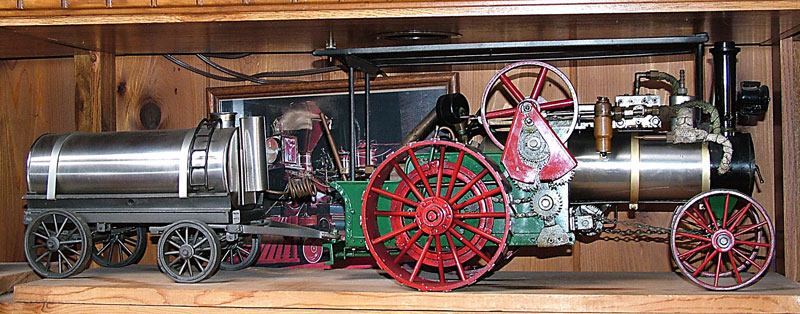

Clarry’s steam locomotives were built to 1″ scale (1/12 size), with the track about 4″ between the rails. Some of his larger boats were built to 1/2″ scale (1/24 size), while his largest Case tractor was built to 2″ scale (1/6 size). This was because of the large amount of detail in the tractor engine. Clarry would usually have at least two projects going at any given time. If a problem or lack of material brought one project to a halt, Clarry could always stay busy with the other one.

Ironically, what began as a relaxing retirement diversion had soon become somewhat of an obsession. Clarry admitted that he would get anxious if he didn’t constantly have at least one project in progress. He added, “I try to keep a lot of materials on hand so I don’t have to go looking for it when I need it.” Additionally, Clarry did a lot of research on each of his models, and would draw a full set of plans to scale before starting any project.

With each new machine that Clarry made, he wanted to do two things: the first was to challenge himself each time with an engine that was different from any of his previous models; and the second was to duplicate whatever he was modeling to the most exact degree possible. Clarry would even purchase tin soldier figures, and transform them into workers for his models—adding a human touch.

When it came to his work, Clarry thought of his machines as “elegance in steel.” He considered working with metal to be more difficult than working with wood. Clarry remarked that, “If you make a mistake in metal, you have to throw it away and start again,” according to a 1989 article from a local San Diego newspaper.

Over the years, Clarry and his engines received exposure through several newspaper articles. He would also show his engines at the San Diego County Fair in Del Mar, and at local libraries. In addition to his modeling skills, Clarry was an accomplished, self-taught musician. He also found the time to enjoy vegetable gardening, as well as collecting aboriginal artifacts.

A scale model traction engine towing a water tank trailer.

Lost Craftsmanship: Thoughts for Other Craftsmen

Though his daughter tried on a number of occasions to talk to Clarry about what he wanted done with his engine collection, he would always avoid the subject. After his passing, all of Clarry’s tools and models were eventually sold at auction in Pennsylvania. The engines are now in the hands of many new owners, most of whom know little or nothing about the builder. To other craftsmen who are reading this section, we would like to urge you to make plans for the future of your work!

Clarry’s busy shop occupied a shed behind his house. It wasn’t far from a small pond that bordered his property, where Clarry could sail his steam powered boats. Rail lines in his yard ran into the shed, for working on and running steam locomotives.

View more photos of Clarry Dawson’s unique collection of machines.